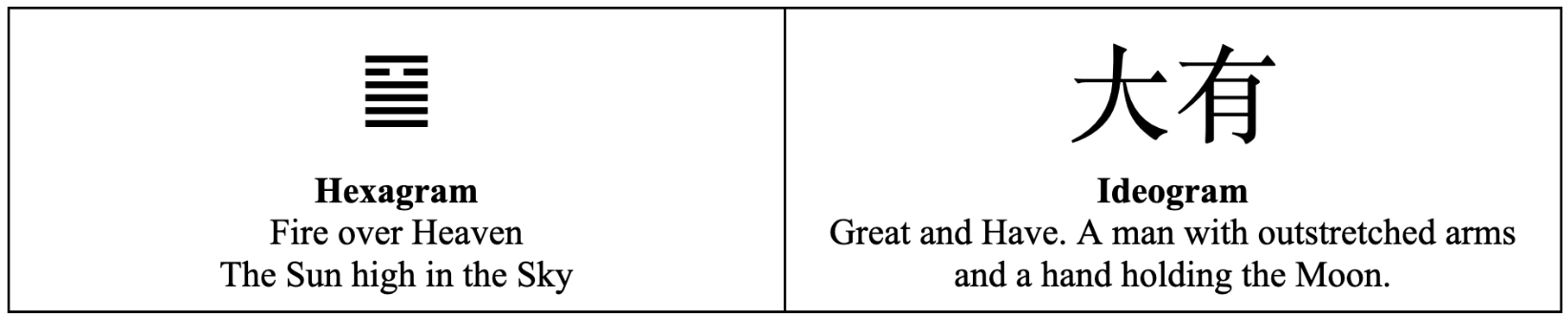

14 Having Enough (Great Wealth) - The I Ching

Chris Gabriel February 7, 2026

Having enough is the origin of prosperity…

Chris Gabriel February 7, 2026

Judgment

Having enough is the origin of prosperity.

Lines

1

Going unharmed.

2

A big wagon carries a load with far to go.

3

The Prince makes sacrifices to the Son of Heaven

4

Without a sound. Without fault.

5

His faith reaches out.

6

Heaven has blessed you.

Qabalah

Tiphereth on the Middle Pillar. The exalted Sun. The 6 of Cups and 6 of Disks, and the Prince of Cups and Prince of Disks.

High in the sky sits the radiant midday Sun. As it rises through the morning, it is satisfied at its zenith, and begins to set, having had enough for the day. While we saw the rising of the sun and of man in our previous hexagram, here we have the apex.

1 At the height of our strength, we will go unharmed. It is a cruel irony, but often it is the weakest who are harmed the most while those with power go unscathed.

2 When we have many things, as those in power tend to, the act of moving becomes a problem. It is easy for someone with nothing to start over somewhere else. This is also the journey of the Sun; we can think of Helios on his chariot who, having reached the height, now starts his journey into the night.

3 In his book The Accursed Share, writer Georges Bataille describes the titular concept as the excess energy in an organism which must be sacrificed:

“The living organism ordinarily receives more energy than is necessary for maintaining life; the excess energy (wealth) can be used for the growth of a system (e.g., an organism); if the system can no longer grow, or if the excess cannot be completely absorbed in it's growth, it must necessarily be lost without profit; it must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically.”

This is especially apt for the hexagram, as he is describing our relation to the “Solar Economy” itself.

“Solar radiation results in a superabundance of energy on the surface of the globe. But, first, living matter receives this energy and accumulates it within the limits given by the space that is available to it. It then radiates or squanders it, but before devoting an appreciable share to this radiation it makes maximum use of it for growth. Only the impossibility of continuing growth makes way for squander. Hence the real excess does not begin until the growth of the individual or group has reached its limits.”

4 Wealth and power do best when they do not flaunt themselves and make noise. It was the superfluous spending of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette that led the people to revolution, and the monarchy to the guillotine.

5 “He” in this case is the Sun, and as Bataille says “Solar energy is the source of life's exuberant development. The origin and essence of our wealth are given in the radiation of the sun, which dispenses energy - wealth - without any return.”

The sun reaches out to us.

6 As we have seen, it is the blessing of the Sun and the Heavens above that create our own power and wealth.

This hexagram is given to Tiphereth, the Solar center of the Tree of Life, the highest self and source of our higher nature. Though Hexagram 30 shows the direct nature of the Sun, we see here what the Sun does in relation to humanity.

Let us then know when we’ve accumulated enough wealth and power and give away our accursed share in magnanimity.

Watching the ‘Apocalypse’ On the Set of Apocalypse Now (1977)

Maureen Orth February 5, 2026

It was the middle of the day in the steamy Philippine jungle and the sun was merciless…

Much has been written, spoken, filmed, and discussed about the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s war epic ‘Apocalypse Now’. ‘Hearts of Darkness’, the documentary made by Francis’s wife Eleanor Coppola and released in 1991, has become the definitive account of the legendary production, but Orth’s account, originally published in Newsweek two years before the film was even released, was the first to lift the veil. A work of masterful fever-dream journalism that captures the depravity, absurdity, and insanity of the production, and revealing how the act of reporting becomes inseparable from the madness it describes.

Maureen Orth February 5, 2026

In the tropics one must before everything keep calm. – Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

It was the middle of the day in the steamy Philippine jungle and the sun was merciless. Director Francis Ford Coppola, dressed in rumpled white Mao pajamas, was slowly making his way upriver in a motor launch. “Right here is where we hang the dead body,” he said to his production designer, Dean Tavoularis. “I want skulls – a pile, no, a wall of skulls.” “Can we light this for night?” he asked his director of photography, Vittorio Storaro. Storaro sighed and stroked his beard. “Fires should be burning behind the curtain,” Coppola said to Tavoularis, pointing to a striking red silk curtain that meandered 300 yards along the riverbank. When the boat docked, a set decorator complained, “Where are we going to get 200 skulls?” Tavoularis shrugged. After what he and everyone else had been through, 200 skulls were just so many coconuts.

For over a year, one of Hollywood’s most successful directors (“Godfather I and II”) had been shooting “Apocalypse Now,” a film about the “untouchable” subject of the Vietnam war. It had started in March 1976 as a $12 million movie that would take four months to shoot. Things quickly escalated. By the time the crew finally left the Philippines a fortnight ago, they had become battle-scarred, if well paid, veterans. “Apocalypse Now” had consumed more than 230 shooting days and a million feet of film and will end up costing about $25 million. (A little more than $7 million came from the sale of distribution rights in foreign countries; United Artists says it has put up $7.5 million and advanced the rest to Coppola, who has put up all his own assets as guarantees on the loans.)

Life on the set – four different locations in the Philippines – also escalated quickly to apocalyptic dimensions. The young crew, composed largely of Americans, Filipinos, and Italians, weathered a typhoon, survived dysentery and sweated through day after day of relentless heat – alleviated by periodic R&R trips to Hong Kong. Stuntmen amused themselves by diving from fourth-story windows into the motel pool below. The prop man, Doug Madison, became adept at fabricating top secret CIA documents, thought nothing of driving 400 miles to fetch a special Army knife, and made a connection with a supplier of real corpses – before he was vetoed. At one point, Coppola asked Tavoularis to produce 1,000 blackbirds, which prompted the designer to consider making cardboard beaks for pigeons and dyeing them black. The film company retained a full-time snake man, who appeared every morning on the set with a sack full of pythons. The Italians brought in pasta and mozzarella from Italy in film cans. Did Coppola want a tribe of primitive mountain people living on the set in their own functioning village? He got it.

Replay Of A National Nightmare

At night, General Coppola reviewed video cassettes of the film in his house in Hidden Valley, a volcanic crater, arriving there in a helicopter that he often piloted himself. By the time he finished shooting, he had lost 60 pounds, and the making of “Apocalypse Now” had come to resemble nothing so much as its subject – Vietnam.

For years, Hollywood has ignored Vietnam on the theory that nobody wants to see America’s worst national nightmare replayed. Now, a number of movies are being made about the war, but none so far-reaching as “Apocalypse.” The original script was written in 1967 by John Milius, an unregenerate hawk, but Coppola has reportedly long since abandoned all but the story line to move closer to the script’s original source, Joseph Conrad’s classic study of moral jungle rot in Africa, “Heart of Darkness.” Coppola’s idea has been to make the film on two levels – both as an entertaining war movie full of action, adventure and spectacular special effects, and as a mythical, highly stylized allegory of the American experience in Vietnam in 1968 and 1969 – all of it set to the rock music of The Doors and filled with psychedelic sound and light.

Martin Sheen plays Army Capt. B. L. Willard, hired by the CIA and sent upriver on a Navy patrol boat crewed by Frederic Forrest, Sam Bottoms, Larry Fishburne and Albert Hall. His mission is to kill Coppola’s “Mr. Kurtz,” one Col. Walter E. Kurtz – an officer gone insane – who lives in a temple resembling Angkor Wat across the border in Cambodia, is worshipped by the Montagnards and is played by Marlon Brando.

One of Kurtz’s entourage is a spaced out hippie photographer who’s had about 200 acid trips too many, a role Denis Hopper evolved for himself. Robert Duvall plays another kind of mad colonel who carelessly risks the lives of his men in order to land in a village that has perfect waves for surfing. As Sheen and his crew head upriver, they encounter a wild rock concert during which 300 horny soldiers storm a stage to get at a delegation of Playboy bunnies; a French plantation family determined to hold out at all costs; exploding bridges, and one peaceful group of Vietnamese whom they murder in panic. One helicopter battle sequence, choreographed to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” took seven and a half weeks to shoot and will appear on the screen for only six minutes.

A Film On Two Levels

“I am doing this film half intuitively,” says Coppola, sitting inside his houseboat, where he wrote out the script each day on index cards. “I am spinning a web. The movie has two levels – the level of the life on the boat and the mission and then what happens to Kurtz’s mind when the film becomes a surreal. His mind is blown by the extent of the horror of the war. You have to invent. All I do is see more or less what the truth was and put it in the movie. Of course, the movie has to live in reality and practicality. I’m spending $100,000 a day. Imagine the degree of control I have to have.”

That control wasn’t always easy – to say the least. The first phase of “Apocalypse” ended when the typhoon struck, destroying sets that had taken months to build and stranding the crew in various isolated locations. (One group found itself stuck in a house with a Playboy Playmate, who shut herself up in a room, declaring, “I can do without sex for nine months.”) Even before the typhoon, Coppola fired one of his leading actors, Harvey Keitel, who hated the jungle and couldn’t stand bugs. On the first day of shooting, Keitel and the other actors had been unintentionally left by the camera crew in the middle of the river. “Hello,” announced Keitel fruitlessly into his walkie-talkie. “Hello, this is Harvey Keitel.” Silence. “This is Harvey Keitel.” Silence. Then: “You wouldn’t do this to Marlon Brando. You wouldn’t do this to Marlon Brando.”

“It was hell for a while at the beginning of the movie,” says Gary Fettis, a crew member. “Mostly because Francis was getting ripped off by the Filipinos. Artistically, Francis didn’t know what he was going for and he was a pretty hard guy to be around. The crew didn’t know he didn’t know. But when you’d see him typing away in his houseboat in the mornings, you suspected as much. It created a sense of chaos.”

When Brando showed up last fall with an entourage of seven (his fee for five weeks’ work was $1 million), Coppola still hadn’t written the ending to the movie. He finally shut down production for a few days to talk about Conrad with an old pal from film-school days at UCLA, Dennis Jakob, a fanatical lover of Nietzsche’s philosophy who became the movie’s intellectual catalyst. He also spent hours discussing the war in Vietnam with Brando, and tapes of those conversations figure in the film.

“He piled up garbage. He spread blood and skulls all around. He got old bones from a restaurant in Manila. Rats arrived on the set and people began to complain of the stench of festering flesh.”

A 285-Pound Star

“I tried to write the end in which Kurtz goes mad, over 100 times,” says Coppola, “but I didn’t know what Marlon would look like or how much he would weigh. I went to bed every night at 4 a. m. and told my wife, if she was there, ‘I can’t write it, I can’t write it’.” In fact, Brando showed up weighing 285 pounds, so Coppola decided to make Kurtz 6 feet 5 inches and do most of his body shots using a 6 foot 5 inch double, a coloful ex-boatswain’s mate in Vietnam named Pete Cooper who ran the boats for the crew and served as military adviser to Coppola. Brando shaved off all his hair for the role and requested 5-inch lifts on his shoes to get the feel of the part. On the first day he wore the lifts, he twisted his ankle and retreated at once to his trailer.

Members of the crew refused to ride in a bus with Dennis Hopper, who wore the same set of clothes for the two months he was there. Last March, Keitel’s replacement, Sheen, a 36 year old physical-fitness buff, suffered a heart attack during a 6-mile jog in the 100 degree heat. Sheen, who recovered six weeks later, thinks his attack was precipitated by his own death fears triggered by working on “Apocalypse Now.” “The film really scared the hell out of me,” he says. “I discovered through my sickness that I was acting out my mother’s death. She also died thousands of miles away from home of a heart attack.”

Coppola was forced to rely on the Philippine military for personnel had equipment, since the U.S. Department of Defense refused to cooperate with the project in any way. (Coppola sent angry cables to Washington, D. C., claiming that Defense was harassing him.) On the first day of the big helicopter scene last summer, according to some reports, a Filipino officer pocketed the $15,000 out of which he was supposed to pay his pilots, and the next day the pilots refused to work. Almost every day thereafter, they made new demands for money on the film company – which had come to be regarded in the local countryside as a cross between an invading army and Santa Claus.

Pagsanjan, the sleepy river town north of Manila where the “Apocalypse” crew had its headquarters, had been accustomed to an average wage of less than $2 a day. But for nine months, the movie company pumped in $100,000 a week there. As a result, the robbing of local coconut plantations stopped, rents for homes shot up astronomically, and every night the high-school principal, Ricardo Fabella, went from bar to bar in his jeep urging the Filipino film workers not to waste their windfall wages on liquor and women. “Our people have lost their sense of values,” he said. “Everything I’ve taught them they’ve forgotten.”

At one lavish party Coppola threw to thank the residents of Pagsanjan for their cooperation, he heard himself praised by the governor of Laguna Province as the best ambassador the U.S. ever sent. The next speech was from the local prosecutor who, before he picked up the microphone to sing with the band, mentioned two lawsuits against “Apocalypse” – one for the mutilation of birds (both suits were later dropped). He turned over the mike to Coppola, who serenaded the crowd with “‘A’ You’re Adorable.” “It’s either here or Beverly Hills,” Coppola called to his wife. “Let’s stay here.”

Everything But Real Bullets

Because of the film’s vast arsenal of explosives and weapons, the set was heavily guarded at all times. Coppola was driven by a member of President Ferdinand Marcos’s personal staff. For one scene involving 2,000 South Vietnamese troops and villagers, the film-makers recruited several hundred South Vietnamese refugees. The Philippine Government supplied eighteen helicopters, which were outfitted with new rotor blades and converted into gunships for the Philippine Air Force at the film company’s expense. Dick White, an ex-Vietnam helicopter flying ace and daredevil, supervised the air sequences. “This movie has everything but real bullets,” he says. “With my helicopters, the boats and the high morale of the well-trained extras we had, there were three or four countries in the world we could have taken easily.”

But the longest running real battle on the set was over what the film was really about. “What Francis is trying to say,” says Brando’s stand-in, Pete Cooper, “is that the military people were not second-class citizens and idiots. They were good hometown boys, but the war changed them. The whole military image is going to be changed after this.” “I hate to say it,” says special effects chief Joe Lombardi, “but this whole movie is special effects. You got three stars but the action’s gonna keep the audience on the edge of their seats. It’s a war movie.” “This movie’s about how wrong it was for Americans to go against their nature,” says Dean Tavoularis.

Still, everyone was loyal to the general. One of Coppola’s skills as a director was that he was able to make everyone give his all.” Francis wanted to get me and Dick White drunk and listen to war stories,” says Cooper. “I didn’t want to. For the first four months of this film I was screaming in my sleep – reliving it all. But in the military you’re taught to follow orders. Francis is a brain drainer. You sit with him for ten minutes and he absorbs everything in your body.”

It’s hard to say who gave the most, but nearly everyone agrees that a great catharsis came at Kurtz’s compound – a hot and humid pit a half mile long. The temple inside the pit was destroyed by the typhoon, and was reconstructed with 300-pound blocks placed mostly by hand. To express Kurtz’s “horror,” Tavoularis, who describes his life as “a shambles” after working two years on the film, let his feelings of depression and alienation run wild. He piled up garbage. He spread blood and skulls all around. He got old bones from a restaurant in Manila. Rats arrived on the set and people began to complain of the stench of festering flesh.

“Francis and I reached the same point through different channels,” says Tavoularis. “We both did it by going through a certain madness. He was feverishly rewriting the whole end of the film, talking to Marlon and Dennis Hopper. I was living the house of death I was making. It became such a low level in my life that somehow putting blood on staircases and rolling heads down steps seemed natural to me.” The experience went on for weeks. “There were times,” remembers Delia Javier, a Filipion crew member, “when I feared the consequences for my psyche. Then one night everything fused together. It was what Christians call a miracle.”

Part of the credit for the miracle goes to 250 fierce and primitive Filipino mountain tribesmen, the Ifugaos, still head-hunters during World War II, who were brought from the north to live on the set at Kurtz’s compound. “People said the Ifugaos were very calming in the craziness,” says Eva Gardos, a former Harlem schoolteacher, who was sent to the mountains of the northern Philippines to find “some primitive people” at Coppola’s request. In order to lure the Ifugaos south, Gardos promised them a weekly supply of betel nuts and, in case any of them got sick, live animals for sacrifice.

Four Blows Of The Knife

Brando invited the Ifugaos to his big welcoming party, complete with ice Oscars lighted from inside, spectacular fireworks and a magician. They loved the fireworks. Coppola incorporated Ifugao ceremonies and dances into the film; they were also taught to use guns and to sing – phonetically – ‘The Doors’ “Light My Fire” to the accompaniment of their own instruments. Although they generally were shy, one teenage Ifugao girl got friendly enough with make-up man Fred Blau to ask if she could borrow his tape of John Denver’s “Greatest hits.”

In honor of Coppola, the Ifugaos re-enacted their sacred sacrifice of a water buffalo and Coppola has used this on film as one of his story’s most important symbols. “First the Ifugaos talked to the water buffalo for two days and told it not to be afraid of death,” reports one extra. “Then they killed four pigs and sacrificed a chicken. The meat was passed around and eaten, sometimes raw. Then the elders took long knives and gave the buffalo four blows at the back of the neck. During this time the water buffalo didn’t utter a sound, but he had a big tear in his eye – he really did. Wham, the fourth blow killed him. In the film, Sheen kills Brando the same way.”

Is America ready for “Apocalypse Now”? Just to make sure, United Artists is paying a half million dollars on two political miracle workers – Jimmy Carter’s media consultant Gerald Rafshoon and pollster Pat Caddell – to help Coppola’s staff devise a marketing strategy for the three-hour-plus film. The film is scheduled, if all goes well, to open in Decemmber. It will be shown on a reserved-seat basis at increased admission prices. Caddell’s poll ranges from measuring the impact of Vietnam to finding out how many people know the meaning of the word “apocalypse.”

Maureen Orth (b.1943) is an American journalist and writer. Orth began as one of the first women writers at Newsweek and is currently a Special Correspondent for Vanity Fair,

On the Termite

André Castor February 3, 2026

Termite mounds - those brown piles of rigid dirt that protrude from the landscape and hide acreage below them - are as ancient as the land they rise from…

Shrine in a termite mound, Kolwezi, Congo, c.1930.

André Castor February 3, 2026

Termite mounds - those brown piles of rigid dirt that protrude from the landscape and hide acreage below them - are as ancient as the land they rise from. In parts of Africa, South America, and Australia, these earthen towers are not just temporary homes, they are enduring monuments, passed down through the generations of termite colonies. Some mounds are known to be over 34,000 years old, but most at least number in the hundreds of years, surviving across centuries and millennia, continually inhabited and rebuilt by successive colonies.

When we think of buildings and cities, we often imagine them as symbols of human ambition, crafted to last for centuries or successive lifetimes. Yet, the termite mound offers a humbling contrast. Here, time itself does not belong to the individuals who build it, but to the community that comes together—over and over again—to tend to it, to repair it, and to keep it alive. It is not a static monument to human achievement, but a living, breathing testament to the persistence of purpose across generations.

The question then arises: What does it mean to build something that outlasts us? What can we learn from these oft-derided insects about living within the cycles of time, about the relationship between the individual and the collective, and about the ways in which our actions are woven into the fabric of a larger, continuous story?

Built by colonies of termites to serve as both nests and climate-controlled environments, these mounds are constructed from earth, saliva, feces, and other organic matter, which is collected by the termites from their surroundings. The architecture is remarkably complex, with a series of tunnels and ventilation shafts that regulate airflow and temperature, providing the colony with a safe, stable environment carefully controlled to maintain optimal conditions of temperature and humidity in the face of extreme weather conditions outside. The mounds can rise up to 30 feet in height and span much large areas below the surface, offering refuge and safety from predator.

Termites help improve soil health, promote water infiltration and enhance nutrient cycling through the aeration process of their building. Their mounds act as natural reservoirs, absorbing and slowly releasing moisture to sustain surrounding vegetation during dry periods. Some species of termites even cultivate fungi within their mounds, creating a symbiotic relationship that helps decompose plant matter, contributing to nutrient recycling in the ecosystem. In these ways, termite mounds are not just homes for termites, but vital structures that play an important role in maintaining the ecological balance of their environment. In the process of thousands of years, these insects build not just for themselves, and their future generations, but the world around them.

“Decay is not the end of things, it is a necessary part of renewal.”

Termite mounds are a reminder that individual lives are but fleeting moments in the vast expanse of time. What these creatures leave behind, in lives that usually last no more a few years for workers and perhaps a few decades for the Queen, is not just the work of a single generation, but the shared contributions of thousands of generations. Each mound is built, maintained, and inhabited by countless termites over thousands of years, but it is always the same mound, never fully finished, always in the process of becoming. The generations may come and go, but the mound itself endures. They are constantly being rebuilt, repaired, and adjusted. They are living structures, continuously in flux, responding to the demands of the environment, to the needs of the colony, and to the rhythms of life itself. Nothing about the mound is static. It is a cycle of construction and deconstruction, creation and decay, over and over again.This challenges the human tendency to view our lives as distinct and separate from one another, as if each of us is isolated in time. How often do we build lives as though they must stand alone, seeking personal recognition, fame, or success? The termite mound offers us a different way of being: a life that belongs to something greater, a purpose that extends beyond the self. The mound’s continuity suggests that the most meaningful actions are not those that bring fleeting personal glory, but those that contribute to a larger, ongoing process—one that connects generations, that transcends time.

For humans, the idea of impermanence is often uncomfortable. We are taught to chase stability, to fight decay, to preserve what we have for as long as possible. But there is a wisdom that we often overlook: decay is not the end of things, it is a necessary part of renewal. The cycles of life, growth, and decay are not to be feared, but understood as fundamental to the very essence of existence.

What if we understood our lives not as isolated projects but as part of an ongoing story—one in which we participate, but do not control? What if our actions, like the termites’ construction of their mounds, were not aimed at permanence or recognition, but at fostering a deeper, intergenerational connection to something larger than ourselves? The mound teaches us that the highest form of meaning may lie not in building for today, but in building for tomorrow, and for the communities that will follow us.

André Castor is a conservationist and researcher who writes about the natural world.

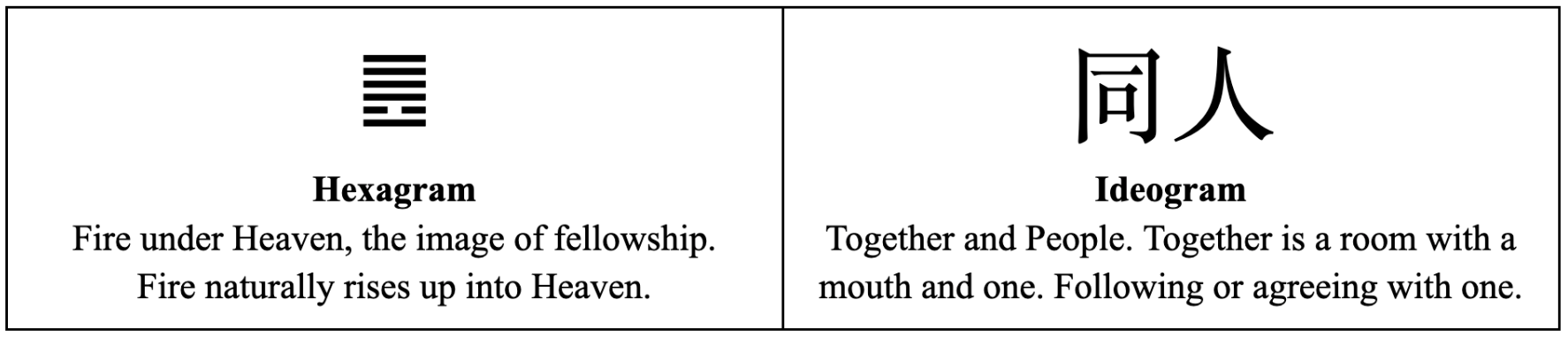

13 Coming Together - The I Ching

Chris Gabriel January 31, 2026

Together in the wild. Cross the great river…

Chris Gabriel January 31, 2026

Judgment

Together in the wild. Cross the great river.

Lines

1

Together at the gate.

2

Together at home.

3

Hiding weapons in high grass. Climbing the high hill. He doesn’t rise for three years.

4

Climbing the wall, but unable to attack.

5

Together we cry, together we laugh. Great leaders meet.

6

Together in the country.

Qabalah

Tiphereth to Kether: The Path of Gimel. The High Priestess.

Here the connection is made from below to above, the Solar Tiphereth seeks to rise to the Heavenly Kether.

In this hexagram we see the rising sun, coming together with the sky. It is pure heat rising. This hexagram is the perfect opposite of hexagram 6 - water under heaven - in which rain splits away from the sky. When fire is below heaven, it moves up. As such, the lines of the hexagram show a progressive coming together of people from within to without.

Judgment: A group of people together in the wild crossing a great river conjures thoughts of the teamwork it takes to “build bridges”, both literally and metaphorically. We can also see the other side of this; crossing the Rubicon and marching on Rome. A group of people cross the river to make everyone join their circle.

1 The group is at the gate, the first impasse. They remain on the boundary. This, again, can be understood in two ways: either as a force seeking to expand into territory out beyond the gate, or they may be the idiomic “barbarians at the gate” seeking to get in.

2 A group at home, amid family. This is a very small community, built on a base natural sympathy. It has no need to spread out. This is the natural human state, totemic and clannish. Getting people to come together was a great labour of history; the combining of disparate families and clans to form cities, states, and empires, against their own selfishness is extraordinarily difficult.

3 When outmatched, it’s best to hide one's strength and wait it out from a good vantage point. It’s useless to fight impossible odds.

4 One climbs the wall to fight the city, but they lack the force to achieve their goals.

5 After much commotion and turmoil, victory comes and peace is made.

6 People have gathered together. From the gate, to the homes, to the whole city, and now the country, but it has not yet reached past itself, the group has not satisfied its expanding desire for empire.

“The Sun never sets on the British Empire.” The rising sun of the hexagram shines its light first on very little, and then on more and more. This is the human desire to gather people together, to have dominion and expand our control. The familial clan shown in line 2 come to control the country in line 6, so we consider the actions necessary for one family to gather its allies and take control of a country. Or how an individual man, like Caesar, can create an empire. This is not solely through violent conquest, as Abraham Lincoln proves in his famous line “Do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?”

Just as the Sun rises and falls, so too do Empires, families, and groups. As Hawthorn says “Families are always rising and falling in America.”. While all powers are destined to fall, the time indicated by this hexagram is that of their rising.

Shadow Work in Ancient Egyptian Magic

Molly Hankins January 29, 2026

In Biblical terms, the Egyptian concept of ‘shew’ is expressed as a revealing of what’s hidden, whereas ancient Egypt’s great mystery schools are thought to have treated shew as the shadow-self that needs the light of consciousness shone upon it in order to be integrated…

Molly Hankins January 29, 2026

In Biblical terms, the Egyptian concept of ‘shew’ is expressed as a revealing of what’s hidden, whereas ancient Egypt’s great mystery schools are thought to have treated shew as the shadow-self that needs the light of consciousness shone upon it in order to be integrated. Author, vocal coach, and archangelic channeler Stewart Pearce explained the nature of shew in his book Angels and the Keys to Paradise. He writes that to name individual aspects of our shew is to, “identify that aspect of self that dwells far from the light, and therefore is the part that most desires reintegration with the light, with the collective soul.” This yearning to merge the seen and unseen worlds is natural. If we are all sparks of consciousness from the original Creator, we are not designed to ignore what we create. Pearce contends that integration of all our creations is essential to our development both spiritually and magically.

“Thinking and feeling negative shadow complexes sabotages our creative energy within the dynamics of the universe. Carl Jung suggested that, ‘One doesn’t become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but rather by drawing the light into the darkness, and creating a light filled consciousness.’ As we identify, purify and redistribute the energy of our shadow from within, more space is created within our cells for light to reside,” Pearce explained. From the perspective of Egypt’s mystery schools, physical changes occur as light is shown in the darkness of our psyches. The idea of ‘light’ here is not a metaphor because light is considered intelligent, and bringing this higher intelligence into our beings by consciously calling in the light gives us access to both expanded awareness and magical abilities.

The magic Pearce refers too is defined by the famous occultist Aleister Crowley as, “The science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will.” Developing this capacity means shedding light on any shame or regret blocking the light of higher intelligence, and therefore blocking our ability to act as co-creators of our reality. Pearce believes that what Egypt’s mystery schools were pointing to with their emphasis on integrating the shew is that our shadow can be a portal to the Creator and to working with what he calls ‘Source Energy.’ Consciously shining light on our shew disrupts the ‘karmic holding patterns’ living in our tissues and keeping us in the karmic wheel of repeated reincarnation in order for our consciousness to evolve. Shew work allows us to choose our own path to conscious evolution, rather than relying on the karmic algorithm to furnish experiences for us that force us to evolve.

“If we bring enough of our shew out of darkness we can begin working directly with collective consciousness to affect change on a global scale.”

This shew integration process, which Pearce also calls “dissolving our darkness,’ has certain thresholds to cross as our consciousness evolves. With each milestone, we can begin using our will to create effects at a global and even galactic scale. When we reach enlightenment, we gain the ability to co-create directly with Source Energy. Over the course of many lifetimes, if we bring enough of our shew out of darkness we can begin working directly with collective consciousness to affect change on a global scale. Pearce, who channels the archangelic collective that provides much of the information in his writing, believes we must dissolve 85% of our darkness in order for our will to begin expressing at the level of global consciousness. Symptoms of having crossed this threshold include drastic upticks in synchronicity and seeing ideas we thought were unique to us expressing within the global collective.

Once 90% of our shew is integrated, we can work at the galactic level. This essentially means that we become pawns on the chessboard of life with a sufficiently developed consciousness to be worthy of being played by higher dimensional entities, known in ancient Egyptian mythology as gods. In previous articles on the nature of personal alchemy, we explored how alchemizing our negative emotions prepares our being for magical practice and the ability to “hold” more high dimensional intelligence within our physical vessels. Our ability to co-create and perform magic with greater impact comes from working with increasingly powerful higher dimensional intelligence. From this point, we gain intelligence by virtue of our expanding access and integrate even more of our shew, so we’re heading towards the 95% threshold of enlightenment.

When we’ve cleared enough shew to be able to embody our own higher consciousness and share consciousness with intelligent beings far greater than ourselves, our vessels are prepared to hold the light of Source Energy. This is where we cross the threshold of enlightenment, and as Richard Rudd of the Gene Keys says, the process of getting there can be blissful and playful. Of course there is suffering along the way, but we help each other find bliss and play anyway. Only the presence of undissolved shew can cast darkness enough to block the light, and only when we are able to face those parts of ourselves by consciously seeking out and integrating them, can we begin integrating with Source and experiencing higher consciousness on Earth.

As author and channeler Tom Kenyon put it in his book The Hathor Material, “The goal is not to merely ascend to another octave. The goal is to live our lives as fully and as richly as possible, constantly surrendering to the greater power of love and awareness. Our advice would be not to concern yourself with timetables and phenomena. They will take care of themselves. Besides, they are of such cosmic proportion as to be immune to your thoughts and interventions. It would be far more beneficial to change those things you can, and what you can affect is the amount of love you bring to the world." That change starts with loving the parts of ourselves, of our shew, that we’re afraid or ashamed of.

Molly Hankins is an Initiate + Reality Hacker serving the Ministry of Quantum Existentialism and Builders of the Adytum.

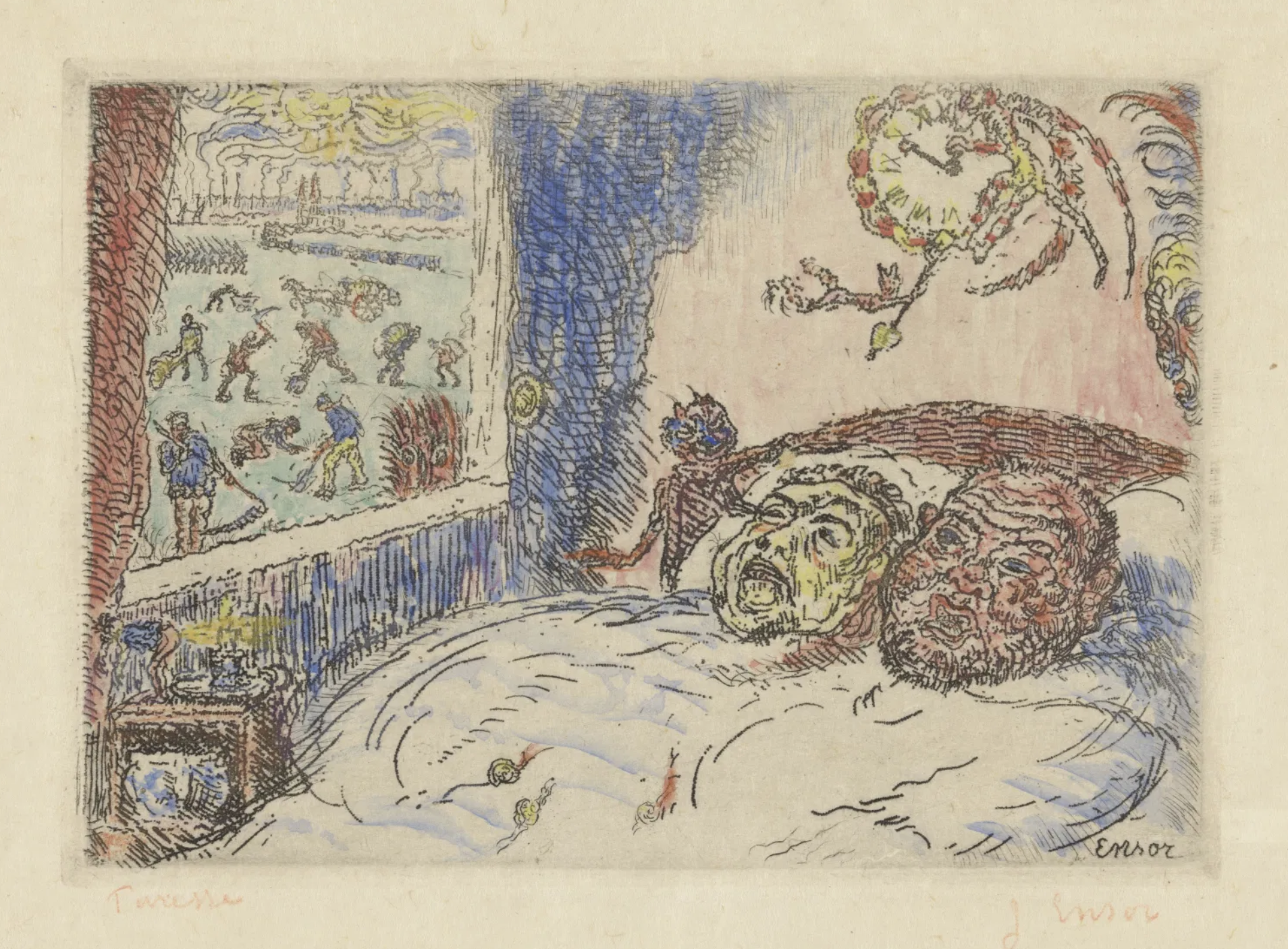

From Cynicism to Sincerity

Noah Gabriel Martin January 27, 2026

The key feature of what I’ll call the 90s West Coast slacker accent is that the tone dips at the end of a phrase, like an inverse question…

Sloth, James Esnor. 1904.

Noah Gabriel Martin January 27, 2026

The key feature of what I’ll call the 90s West Coast slacker accent is that the tone dips at the end of a phrase, like an inverse question. It doesn’t indicate conviction, however. Instead, the slacker tone is all about ironic detachment; it allows the speaker to say something while signalling that they don’t care about saying it, each claim a candy wrapper thoughtlessly dropped to the floor as they keep on walking.

The purpose of the slacker tone is to distance the speaker from what they’re saying, to show that they can’t be found in their words, that the things they say can’t be used to identify them, who they are, or how they feel. The arc of the pitch descends just as each sentence concludes, like a slash crossing it out as it tumbles off their tongue.

That’s not to say that what they’ve said isn’t true, or even that they don’t believe what they’re saying, just that what they’ve said doesn’t matter to them, and the fact that they’ve said it shouldn’t be taken to mean that that’s how they feel. In short, the slacker tone is a disclaimer that alienates sincerity.

Why say things if they don’t care about them? It’s a puzzle, but the greater mystery is why a whole generation might adopt a tone of voice contrived to undercut each expression, signaling that the things we say are of no importance and shouldn’t be taken seriously. What would motivate us to systematically undermine the power of our own speech?

The slacker tone of voice has frequently been conflated with sarcasm. In fact, the quintessential example of slacker voice is from a 1996 episode of the Simpsons - one punk says “Are you being sarcastic, dude?” to another, who responds “I don't even know anymore.” He doesn’t know, because he hasn’t decided to be sarcastic; to reject as false and even worthy of ridicule the position he’s aping. The slacker voice is more ambiguous than sarcasm, it doesn’t reject the thing being said, thereby actually taking an affirmative position contrary to it; it refuses to take any position at all. If sarcasm announces, with ridicule, that you don’t agree with the semantic content of what you’re saying, a slacker tone makes it impossible to tell what you believe in, or if you believe in anything at all.

The Simpsons’ calling attention to this voice is a distraction from the fact that this snark was the entire style of The Simpsons; the undecided, un-pin-downable position which disowns everything and affirms nothing was characteristic of its era, and The Simpson epitomised it. It treated the mainstream with irreverence, without actually taking up a position against it. It dismissed all seriousness as equally ridiculous, refusing to look at whether some positions might be more worthwhile than others.

The Marxist cultural critic Frederic Jameson, called this style of speech ‘pastiche’, and it was marked by a refusal to sign onto any political project and fight for it. He identified it with a postmodern rejection of commitment to the truth and value of any political cause. Jameson described the kind of parody that isn’t motivated by belief in something, exactly the kind of parody we see in The Simpsons, as ‘parody without a vocation’ or ‘parody with no target’ and nothing to defend. “It is a neutral practice of such mimicry”, he said, “without any of parody’s ulterior motives, amputated of the satiric impulse, devoid of laughter and of any conviction that alongside the abnormal tongue you have momentarily borrowed, some healthy linguistic normality still exists.”

Growing up as a precociously jaded teenager on the Westcoast, the freewheeling, mainstream, equal opportunity cynicism of The Simpsons was exciting. Maybe we didn’t need a programme; maybe it was enough to satirically lay waste to the corrupt pieties of earlier generations. I didn’t think the onus was on us to replace it with a platform of our own. In fact any positive ambition seemed arrogant; indulgence in the hubristic naivety of thinking you’ve got all the answers. The important thing didn’t seem to be to change things, the important thing was not to fall for the bullshit.

“The fear of being a dupe makes us stupid, because it gets in the way of our sensitivity to differences between more and less dangerous errors.”

What I didn’t understand then was how well this callow nihilism plays into the hands of the status quo. Established power is victorious by default, and the fight against it is an uphill battle. All that’s necessary for those in power to maintain their privilege is for nothing to change, they have inertia on their side. Cynicism, scepticism, and nihilism, even if it takes swipes at the status quo, always ultimately reinforces it.

To have a chance, the side of change needs to offer something. It’s not enough to destroy. To become real, the will to change must create.

That’s why, far from bringing down the system, the snarkiness of the 90s could only engender nastier and nastier iterations, from Family Guy to the Pepe and Soyjak memes on 4chan and 8kun image boards. Because it eschewed sincerity as “cringey” from the start, this caustic sense of humour could never give rise to hope. However, it could curdle into a politics that used jokes to conceal a very real lust for the free expression of cruelty and hatred.

90s slacker indifference also served a deeper political and social need: ego defense. Its linguistic detachment is there to protect the speaker. But to protect against what? What could pose so general a threat that any sincerity, no matter how righteous, would leave one open to it.

The American Pragmatist philosopher William James criticised undue skepticism as the ‘fear of being a dupe’.

The problem, according to James, with the ‘fear of being a dupe’, or what most philosophers would call ‘epistemological responsibility’, is that trying to make sure we never fall into error gets in the way of a tremendous amount of learning, discovery, and even of finding truth. Many of the most urgent and momentous questions we face in life - whether and who to marry, what career to pursue - cannot be decided one way or the other, so we frequently find ourselves in a position of having to take leaps of faith, or to put it more ecumenically, to form beliefs and make choices on insufficient grounds. To do that, we’ve got to let go of the fear of error, lest we remain paralysed by it.

The fear of error, in James’ interpretation, is a kind of phobia. It might be understood as a sort of psychosocial autoimmune disorder, and like any autoimmune disorders, it’s a dysfunction in our self-defenses that not only directly harms us, but makes it hard for us to protect ourselves when we have to. Fear of error produces a kind of autonomic stupidity that destroys the body and mind’s ability to distinguish between what’s harmless and real threats.

The fear of being a dupe makes us stupid, because it gets in the way of our sensitivity to differences between more and less dangerous errors. Not all errors are equally dangerous; an unjustified belief in the stability of nuclear détente is more dangerous than an unjustified belief in the benefit of community, but if we’re overly concerned with avoiding any error at all, it makes it a lot harder to appreciate the difference.

The detachment of the slacker tone is a similar kind of disordered autoimmune response, motivated by an even more fundamental paranoia than James’ ‘fear of being a dupe’ - an abject terror of vulnerability. For the paranoid, the problem with being a dupe isn’t really the error, it’s that one has failed to defend oneself, allowed oneself to be taken advantage of, made oneself vulnerable. Besides being a dupe, there are many other ways of being vulnerable, and we have learned to avoid them all.

The terror of vulnerability, like the fear of being a dupe, is paranoid; it’s got nothing whatever to do with any particular threat. It mistakes defensiveness itself for the point, forgetting that defense should be defense of or against something. As Robert Frost writes:

“Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,”

If we’ve always got our defenses up, there’s no way for us to peek over the parapets to tell if there’s actually something out there to defend against.

It’s this terror of vulnerability that lay beneath the Simpsons’ snark, and 90s slacker culture in general. On the face of it, this kind of detachment might look cool, but when we look under the hood we can see the shaking, timid reality that it’s covering up.

What culture needs instead is the courage to be sincere, to stand up for something, to risk the vulnerability it takes to say clearly, with care and feeling: “this is what I believe in.”

Dr. Noah Gabriel Martin lectures in philosophy at the University of Winchester and runs the College of Modern Anxiety, a social enterprise that promotes lifelong learning for liberation. He recently began to study dance, which has taught him a lot about being an absolute beginner.

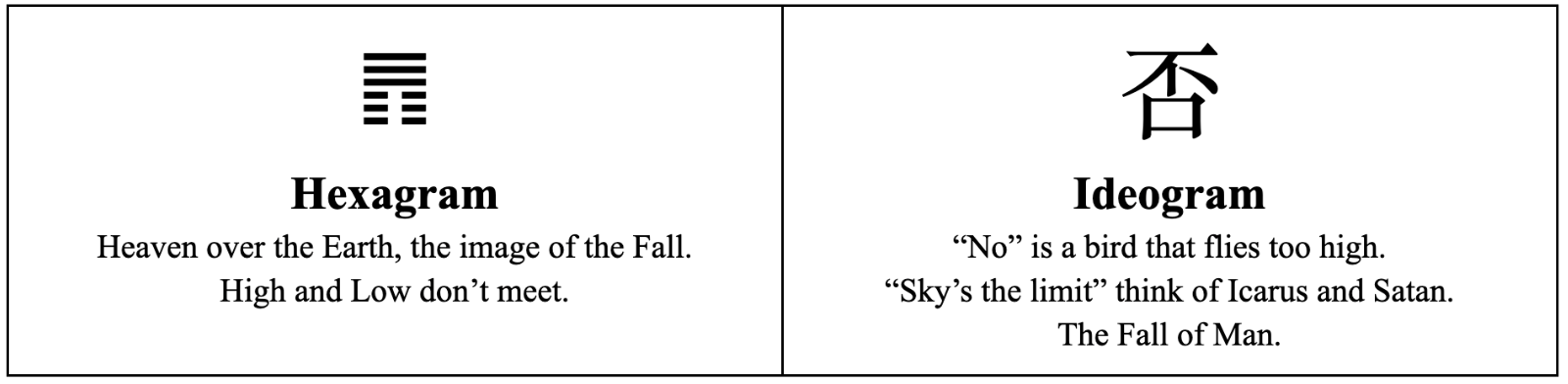

12 No (Evil) - The I Ching

Chris Gabriel January 24, 2026

In a den of thieves, even a Sage won’t thrive…

Chris Gabriel January 24, 2026

Judgment

In a den of thieves, even a Sage won’t thrive. The High has gone, the Low is here.

Lines

1

Pull up the tares and the wheat goes with it.

2

Accept help. It’s good for little people and bad for the great.

3

Accept shame.

4

Accept commandments. Be with your people.

5

Evil is resting. He’s gone! He’s gone! Tied up in the roots of the tree.

6

Evil is fallen. Evil is past, good is here.

Qabalah

“Kether is in Malkuth”

The Ten of Wands and the Ten of Swords

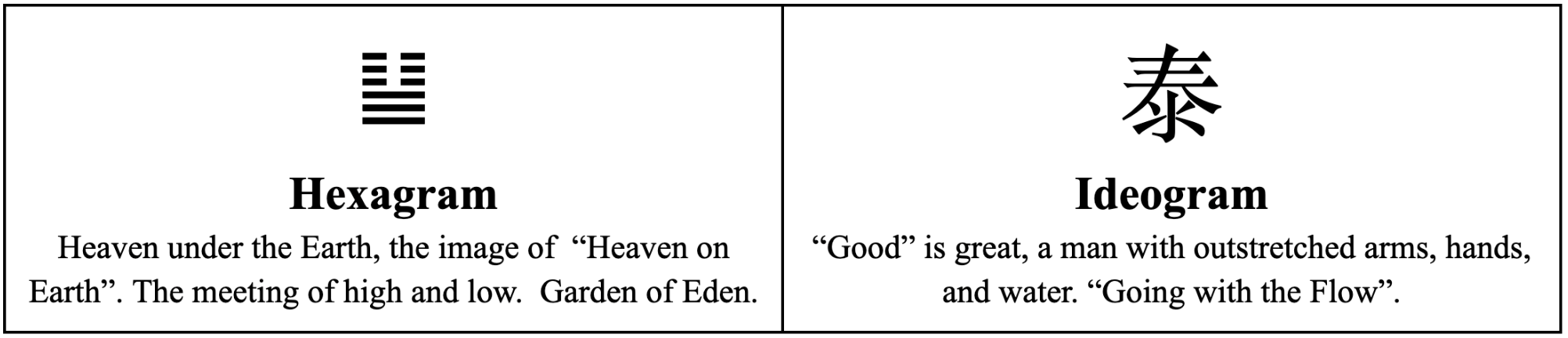

In this Hexagram we are given the image of the Fall itself. The Paradise of our previous Hexagram has returned to the “natural state” where Heaven is firmly above, and Earth is firmly below. The ideogram is the word for “No” and meant “Evil” in the past. A perfect balance to the affirmative “Good” of the previous hexagram;. the image of a thing falling. The text tells us what to do in this fallen state.

The Judgment directly quotes Christ in Matthew 21:13 “My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves. The Holy place has been desecrated, the Divine has left it.

1. The first line is identical to 11’s first line. Previously, one could not uproot weeds without endangering Paradise, here the warning holds. We can’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. Even when times are bad, goodness grows.

2. When we are in a bad state, it is good to receive help. This is not the case for those in power. Think of the banks who were bailed out in 2008 while the people suffered.

3. We must accept our condition if we are to improve it. As they often say in 12 step programs “The first step is admitting you have a problem.”

4. When Moses found chaos in his people, he was drawn up to Mount Sinai by God and given the Ten Commandments to bring order to them. In the chaotic fallen state, we need rules and morals to improve our condition.

5. Just as Odin binds Loki in the roots of the World Tree, in Revelation 20 an Angel binds the Devil in chains:

1 And I saw an angel come down from heaven, having the key of the bottomless pit and a great chain in his hand. 2 And he laid hold on the dragon, that old serpent, which is the Devil, and Satan, and bound him a thousand years,

6. As the 11th hexagram ends with a negative fall beginning, this hexagram ends with a “positive fall”: the Fall of Satan., We can place this in a relative temporal sense (for just as in the I Ching, celestial Biblical events are cyclical, not linear) to Luke 10:18:

And he said unto them, I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven.

Satan falls because Christ gives a power greater than the devil’s to his followers.

Qabalistically, we see the divine in the material world, but it suffers. The tarot cards for this hexagram are the Ten of Wands and Swords, Oppression and Ruin. The high struggling in the low.

Even in a fallen state, we can understand our time and make the best of it, readying ourselves to improve the world around us. No matter how bad a time feels, we can know with certainty that it will pass, and ready ourselves for the next time.

The Soul of the Word (1963)

Marian Zazeela January 22, 2026

If I choose to inscribe a word I begin in the center of the page. The word first written is awkward and leans a little to the left.

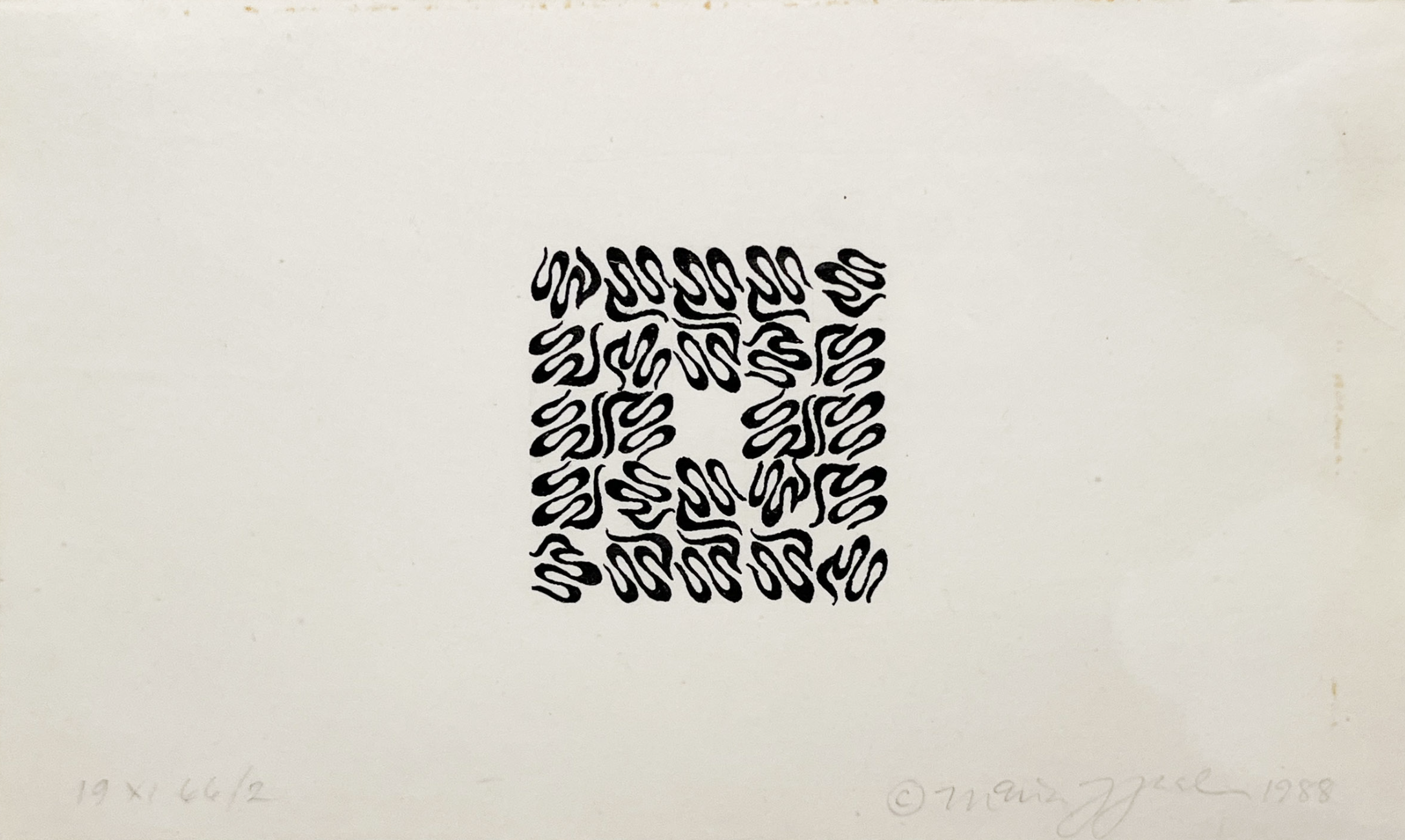

19 XI 66/2, Marian Zazeela.1966.

Marian Zazeela is most known, and her work most often experienced, through her collaborative works with her husband, the composer LaMonte Young. Her light sculptures, album art works, and graphic design work defined the visual and environmental language of 60s downtown New York, but her work as solo artist has long been overlooked, especially her calligraphic creations. In this short essay, first published in the legendary Aspen Magazine in 1971 but written nearly a decade prior, she described her process of making letters. For Zazeela, the letter is a living thing that she breathes life into through her nib. It contorts on the page, following some unknowable natural order for which she can only act as a vessel for facilitation.

Marian Zazeela January 22, 2026

If I choose to inscribe a word I begin in the center of the page. The word first written is awkward and leans a little to the left. I go over the letters adding characteristic curves, making the lines heavier. The letters grow larger, extend curled tentacles out toward each other, begin rubbing and burying their shoots in each other. I move the pen from left to right adding ornaments. The word begins to act as a single unit. Repeated strokes perform continual changes as the letters shift and grow.

The word is still discernible. A sweeping ornament is fastened to the first letter which is now perfect and needs no adjustment.

Now the end letter must have a flourish giving the extra length needed to be exactly centered. Some of the letters have sent wriggling lines beneath them and the balance again requires correction compensation. The word has now spread out of its letters. The letters are more and more obscured as the writing takes precedence. The word no longer matters; it can be spoken.

But the writhing rising out of the word is a dragon devouring itself. Like a cat cleaning her fur the tongue of the word licks its scales with flame and the body of the word ignites and takes the shape of its destruction, which must be perfect and lie perfectly still in the center of the page. if it happens, as it sometimes has, that the flames are not satisfied by the assumption of the word alone, and continue to writhe and curl then the soul of the word is imprisoned and must be set free. And the flames must be slowly brought to the edge of the page where the cool sea waters will soothe them and let them rest. When the fires die out and only the record of flame remains the soul of the word will be carried out to sea and be born again in a raindrop. While it falls to earth in this form it perceives everything through the distorted lens of water; then as it hits the ground all these preconceptions shatter.

But soon the soul of the word is dried and warmed by the sun and feeling drowsy, falls asleep. Upon waking it recalls two dreams: the first, a dream of its future life, tells of the great height it will reach as the soul of a word highly respected by the people, upon whose tongues it will be carried into the richest courts in the world and gently whispered to the ears of noble men and beautiful women; the second dream is the story of its past life but it does not recognize itself in its previous form. Several lives later the dream recurs. Several dreams later the life recurs.

Marian Zazeela (1940 – 2024) was an American light artist, designer, calligrapher, painter, and musician.

Becoming Las Vegas

Jordan Poletti January 20, 2026

If you take the raised pedestrian bridge from the Statue of Liberty, over the 8 Lane Freeway, with the Arthurian Castle on your right, you will find yourself, after being handed a number of call cards for limo-drivers, sex workers and magicians, in the M&M World of Las Vegas Boulevard…

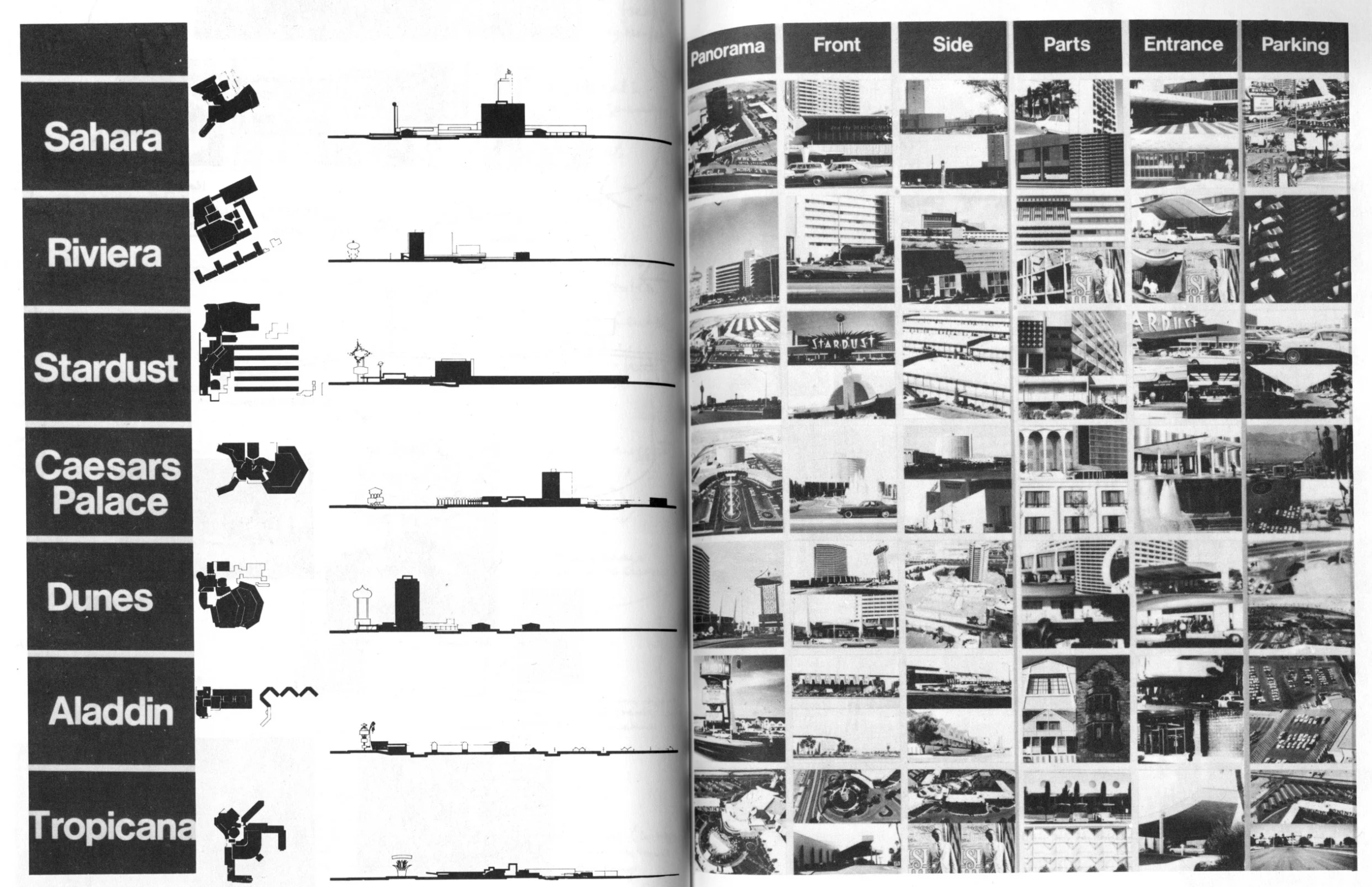

Learning From Las Vegas, Venturi, Brown, Izenous. 1977.

Jordan Poletti January 20, 2026

If you take the raised pedestrian bridge from the Statue of Liberty, over the 8 Lane Freeway, with the Arthurian Castle on your right, you will find yourself, after being handed a number of call cards for limo-drivers, sex workers and magicians, in the M&M World of Las Vegas Boulevard. Nestled neatly into the facade of the MGM Grand, right next to the world's second largest nightclub, owned and operated by a high-end Asian Fusion franchise, it is near identical to the many M&M worlds across the world. If you don't think about it for too long you can make yourself believe you are in Leicester Square, Times Square or Shanghai's People's Square. You wouldn't do this, however, because there is no place in the world you would rather be than right here, the centre of everything and nothingness and very little in between. As you walk through this temple of sugar coated chocolate, peanuts and wafer respectively, you will find yourself no longer in view of the entrance from which you arrived and as you stumble past a 10 foot tube of green candy, you will feel the soft patterned carpet of the MGM Grand Casino. Immediately your tiredness will lift as you breath in oxygenated air and are embraced by the warmth of cigarette smoke and blue-light, epileptic digital screens and the faint click-clack of a roulette ball. If you wanted to return to the M&M world you could not, because the exit has disappeared and it is a one-way porthole that serves a single destination. You will pay a 20 dollar ATM charge to take out not enough money and you will ask yourself the same question that Gorgias, Lao Zing, Descartes, Einstein, David Byrne and Little Simz have asked before you - how did I get here?

If you do not like to gamble, you may well go your whole life without ever visiting Las Vegas. If you do like to gamble, you should go your whole life without ever visiting Las Vegas. But if you have any interest in America, by which I mean modernity, then it is the most important place on Earth. Since its 20th century inception, it has been a city of popular and academic lore, used as muse and message for sin, singularity and separation. A false city who's skyline, Tom Wolfe once wrote, is made up not of buildings or mountains but signage. For the first 100 years of its existence, I suspect the mythification of Las Vegas came from its singularity and its otherness. A city built for a singular purpose of pleasure fulfilment, Versailles it's only equal, and the only legal destination of satiating an American desire for economic self-flagellation. When you arrived on the Strip for 100 years, you encountered novelty, a mirage of simulation and simulacra. Baudrillard's treatise needed no other examples that Las Vegas itself, though only in his later years did he begin to take the city as seriously as he should have. It was Chris Kraus, in her infinite prescience who organised the Chance Conference with Baudrillard in the Nevada desert, placing the father of hyper-modernity in the belly of his patricidal son. It was, he said, and architects, theorist and critics before him, a prototype of the world to come. It's designed disorientation of brash patterns and labyrinthine interiors a far cry from a world still holding onto an enlightenment structure of order and reality. As its neon farms and mob-owned tables were replaced by Eiffel Towers, Pyramids, Gondolas and conglomerates, Las Vegas continued to exist as separate from the rest of the world, updating and adapting to retain its otherness. Where Baudrillard called Disney Land 'miniaturised pleasure of real America', Las Vegas was the miniaturised pleasure of the imaged world. It existed beyond America, a universe unto itself, no longer representing a world but becoming one. It was the only true place in the world, because it cared not for truth, showed there was no truth in the first place, only belief. It offered something separate from daily existence, and this is what gave it its power.

Yet as you stand in the MGM Grand, a bag of M&Ms in your hand, there is little novelty. It feels strangely familiar. You did not get lost on your way here because somehow, the labyrinths of the city felt like you had walked them a hundred times, that the roadmap was embedded in you. This is because the world has caught up with Las Vegas, nearly 100 years later. When Nixon removed the dollar from the Gold Standard in 1971, he made money a simulacra, that which points only to itself, Las Vegas sighed, as it had been doing the same since 1931. Now, it is not just money which is the simulacra but the hyper-reality than Baudrillard talked about has taken is in full force, and Vegas was waiting. On a single junction, outside the M&M world, you can travel through space and time, every corner of the globe and time-period of history. The Statue of Liberty, the Pyramids of Giza, the Eiffel Tower, Caesar's Palace, Medieval Castles. It is no coincidence that the hotels of Vegas are always pointing to something else. They're taking us out of space and time, to a plane not inhabited by context, but a flat circle of shamelessness and instinct. Yet now, this Junction that was once the property of the Nevada desert, exists in the right hand pocket of near ever pair of trousers in the world. We scroll through our feeds and move through time and space. We see a model under the Eiffel Tower and right below it, an aunt by the Sphinx. Between the personal experience we are served ads for hard shell chocolates and pop- ups for daily spins that promise the potential of riches. Brown, Izenour and Venturi told us we must learn from Las Vegas, but instead we have become it. The city understood, long before the rest of the world, that space and time are redundant in the face of desire and satiation. It is the external facade of hyper-reality, of the dissolving of era, country, reality, into a single falsity all while you are crossing that pedestrian bridge above a six lane highway. This is where we are all right now, wavering on the precipice of the M&M World and the Casino beyond it. And we haven't even got inside to gamble yet.

Jordan Poletti is a writer and researcher, focusing on 20th century cultural theory and philosophy.

11 Yes (Good) - The I Ching

Chris Gabriel January 17, 2026

The Low goes and the High comes…

Chris Gabriel January 17, 2026

Judgment

The Low goes and the High comes.

Lines

1

Pull up the tares and the wheat goes with it.

2

Embrace the hard places. Crossing the river, after losing a friend I make it to the middle.

3

Without lows there are no highs. Without going there is no return. It’s tough, but it’s not a problem. Don’t stress. Eat.

4

Fluttering about without wealth. Call on your neighbors, not with demands, but with faith.

5

The Great Emperor marries a commoner.

6

The castle walls have fallen into the moat. No soldiers, so I’ll give my own orders.

Qabalah

“Malkuth is in Kether”

The Ace of Cups and the Ace of Disks.

In this Hexagram, we are once again given an image of something close to the perfection of Heaven: the Prelapsarian World, the Garden of Eden. Unusually here, Heaven, which traditionally remains high, is below the Earth. They are interwoven and unified before the Fall. This is “Heaven on Earth”, but in the text we see that the seeds of decay have been sown, and that this pleasurable condition will not last.

1 The opening line is remarkably close to Christ’s Parable of the Tares in Matthew 13.

29 But he said, Nay; lest while ye gather up the tares, ye root up also the wheat with them.

30 Let both grow together until the harvest: and in the time of harvest I will say to the reapers, Gather ye together first the tares, and bind them in bundles to burn them: but gather the wheat into my barn.

In this line we see the intermingling of the Low and the High, Matter and Spirit, Earth and Heaven. “Et in Arcadia ego” - even in Paradise, evil has been seeded.

2 The condition of material existence necessitates our affirmation of difficulty. We must find the balance in any situation.

3 A profoundly Solomonic wisdom, there is a time for every thing. One could say the I Ching itself is the “clock” that indicates what sort of “time” it is. As for the affirmation at the end, it is a direct mirror to Solomon’s words in Ecclesiastes 9:7 :

Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy, and drink thy wine with a merry heart; for God now accepteth thy works.

4 As in previous hexagrams, we get by with a little help from our friends.

5 In a way, this is another image of the High and Low coming together - the union of the Holy Spirit and Mary, the Divine and the Mundane marrying.

6 By the final line, the condition has decayed. The divine structure has fallen, and individuals must take hold of their own fate.

Qabalistically, this Hexagram illustrates the axiom “Malkuth is in Kether”, base matter exists within the Divine. Before the Fall, God was interwoven with the world. It is the nature of things to change, and accordingly this state of Paradise could never last. Though the state is finite, the hexagram affirms that it does return time after time.

Holy Face (1929)

Aldous Huxley January 15, 2026

Good Times are chronic nowadays…

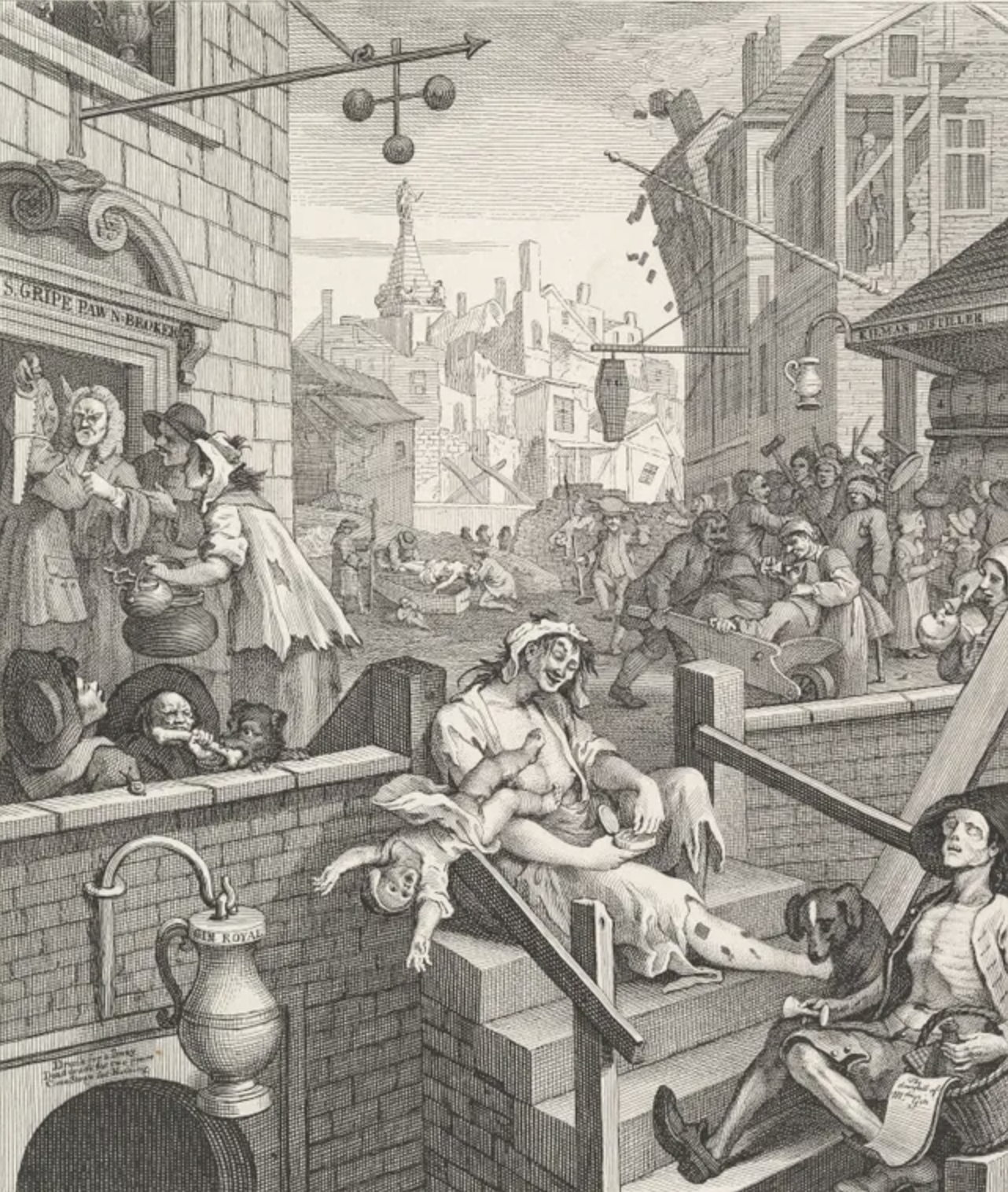

Gin Lane, William Hogarth. 1751.

Before “Brave New World”, Huxley’s seminal and prescient novel about a dystopian future where citizens willingly blind themselves to injustice in favour of ease, Aldous Huxley wrote this essay and chose it to lead one of his earliest collections of his writings. “Holy Face” is a searing critique of the pleasure seeking society, where boredom has become the enemy of existence and we fill our time with fleeting, superficial pleasure in lieu of meaningful thought. This, he argues, is exactly counter to its aim and our desire for quick thrills only creates a more bored society, that must get cheaper and cheaper pleasure to satiate its desire. Huxley, before so many others, saw the pervasiveness of a spiritual emptiness creep into every facet of existence and tried to, by identify it, urge people to reject the systems put upon them as means of control and instead take the reigns of existence, for all its pains and tribulations, as the route to a higher, better life. He uses the religious festival of the Feast of the Holy Face in Lucca, and the acts of devotion occurring around a wooden crucifix bearing the titular ‘Holy Face’, as an example of how we can find deeper meaning in confronting the uncomfortable and the unsettling. After confronting the Holy Face, people instinctively turn back to sunlight, crowds, noise, and the pleasures of the fair outside the church. Huxley sees this instinctive inconsistency as the wiser response. Ordinary people, by embracing both fear and festivity, embody a deeper, unconscious wisdom of life.

Aldous Huxley January 15, 2026

Good Times are chronic nowadays. There is dancing every afternoon, a continuous performance at all the picture-palaces, a radio concert on tap, like gas or water, at any hour of the day or night. The fine point of seldom pleasure is duly blunted. Feasts must be solemn and rare, or else they cease to be feasts. "Like stones of worth they thinly placed are" (or, at any rate, they were in Shakespeare's day, which was the day of Merry England), "or captain jewels in the carconet." The ghosts of these grand occasional jollifications still haunt our modern year. But the stones of worth are indistinguishable from the loud imitation jewelry which now adorns the entire circlet of days. Gems, when they are too large and too numerous, lose all their precious significance; the treasure of an Indian prince is as unimpressive as Aladdin's cave at the pantomime. Set in the midst of the stage diamonds and rubies of modern pleasure, the old feasts are hardly visible. It is only among more or less completely rustic populations, lacking the means and the opportunity to indulge in the modern chronic Good Time, that the surviving feasts preserve something of their ancient glory. Me personally the unflagging pleasures of contemporary cities leave most lugubriously unamused. The prevailing boredom -- for oh, how desperately bored, in spite of their grim determination to have a Good Time, the majority of pleasure-seekers really are! -- the hopeless weariness, infect me. Among the lights, the alcohol, the hideous jazz noises, and the incessant movement I feel myself sinking into deeper and ever deeper despondency. By comparison with a night-club, churches are positively gay. If ever I want to make merry in public, I go where merry-making is occasional and the merriment, therefore, of genuine quality; I go where feasts come rarely.

For one who would frequent only the occasional festivities, the great difficulty is to be in the right place at the right time. I have traveled through Belgium and found, in little market towns, kermesses that were orgiastic like the merry-making in a Breughel picture. But how to remember the date? And how, remembering it, to be in Flanders again at the appointed time? The problem is almost insoluble. And then there is Frogmore. The nineteenth-century sculpture in the royal mausoleum is reputed to be the most amazing of its amazing kind. I should like to see Frogmore. But the anniversary of Queen Victoria's death is the only day in the year when the temple is open to the public. The old queen died, I believe, in January. But what was the precise date? And, if one enjoys the blessed liberty to be elsewhere, how shall one reconcile oneself to being in England at such a season? Frogmore, it seems, will have to remain unvisited. And there are many other places, many other dates and days, which, alas, I shall always miss. I must even be resignedly content with the few festivities whose times I can remember and whose scene coincides, more or less, with that of my existence in each particular portion of the year.

One of these rare and solemn dates which I happen never to forget is September the thirteenth. It is the feast of the Holy Face of Lucca. And since Lucca is within thirty miles of the seaside place where I spend the summer, and since the middle of September is still serenely and transparently summer by the shores of the Mediterranean, the feast of the Holy Face is counted among the captain jewels of my year. At the religious function and the ensuing fair I am, each September, a regular attendant.

"By the Holy Face of Lucca!" It was William the Conqueror's favorite oath. And if I were in the habit of cursing and swearing, I think it would also be mine. For it is a fine oath, admirable both in form and substance. "By the Holy Face of Lucca!" In whatever language you pronounce them, the words reverberate, they rumble with the rumbling of genuine poetry. And for any one who has ever seen the Holy Face, how pregnant they are with power and magical compulsion! For the Face, the Holy Face of Lucca, is certainly the strangest, the most impressive thing of its kind I have ever seen.

Imagine a huge wooden Christ, larger than life, not naked, as in later representations of the Crucifixion, but dressed in a long tunic, formally fluted with stiff Byzantine folds. The face is not the face of a dead, or dying, or even suffering man. It is the face of a man still violently alive, and the expression of its strong features is stern, is fierce, is even rather sinister. From the dark sockets of polished cedar wood two yellowish tawny eyes, made, apparently, of some precious stone, or perhaps of glass, stare out, slightly squinting, with an unsleeping balefulness. Such is the Holy Face. Tradition affirms it to be a true, contemporary portrait. History establishes the fact that it has been in Lucca for the best part of twelve hundred years. It is said that a rudderless and crewless ship miraculously brought it from Palestine to the beaches of Luni. The inhabitants of Sarzana claimed the sacred flotsam; but the Holy Face did not wish to go to Sarzana. The oxen harnessed to the wagon in which it had been placed were divinely inspired to take the road to Lucca. And at Lucca the Face has remained ever since, working miracles, drawing crowds of pilgrims, protecting and at intervals failing to protect the city of its adoption from harm. Twice a year, at Easter time and on the thirteenth of September, the doors of its little domed tabernacle in the cathedral are thrown open, the candles are lighted, and the dark and formidable image, dressed up for the occasion in a jeweled overall and with a glittering crown on its head, stares down -- with who knows what mysterious menace in its bright squinting eyes? -- on the throng of its worshipers.

The official act of worship is a most handsome function. A little after sunset a procession of clergy forms up in the church of San Frediano. In the ancient darkness of the basilica a few candles light up the liturgical ballet. The stiff embroidered vestments, worn by generations of priests and from which the heads and hands of the present occupants emerge with an air of almost total irrelevance (for it is the sacramental carapace that matters; the little man who momentarily fills it is without significance), move hieratically hither and thither through the rich light and the velvet shadows. Under his baldaquin the jeweled old archbishop is a museum specimen. There is a forest of silvery mitres, spear-shaped against the darkness (bishops seem to be plentiful in Lucca). The choir boys wear lace and scarlet. There is a guard of halberdiers in a gaudily-pied medieval uniform. The ritual charade is solemnly danced through. The procession emerges from the dark church into the twilight of the streets. The municipal band strikes up loud inappropriate music. We hurry off to the cathedral by a short cut to take our places for the function.

“Oh, how desperately bored, in spite of their grim determination to have a Good Time, the majority of pleasure-seekers really are!”

The Holy Face has always had a partiality for music. Yearly, through all these hundreds of years, it has been sung to and played at, it has been treated to symphonies, cantatas, solos on every instrument. During the eighteenth century the most celebrated castrati came from the ends of Italy to warble to it; the most eminent professors of the violin, the flute, the oboe, the trombone scraped and blew before its shrine. Paganini himself, when he was living in Lucca in the court of Elisa Bonaparte, performed at the annual concerts in honor of the Face. Times have changed, and the image must now be content with local talent and a lower standard of musical excellence. True, the good will is always there; the Lucchesi continue to do their musical best; but their best is generally no more nor less than just dully creditable. Not always, however. I shall never forget what happened during my first visit to the Face. The musical program that year was ambitious. There was to be a rendering, by choir and orchestra, of one of those vast oratorios which the clerical musician, Dom Perosi, composes in a strange and rather frightful mixture of the musical idioms of Palestrina, Wagner, and Verdi. The orchestra was enormous; the choir was numbered by the hundred; we waited in pleased anticipation for the music to begin. But when it did begin, what an astounding pandemonium! Everybody played and sang like mad, but without apparently any reference to the playing and singing of anybody else. Of all the musical performances I have ever listened to it was the most Manchester-Liberal, the most Victorian-democratic. The conductor stood in the midst of them waving his arms; but he was only a constitutional monarch -- for show, not use. The performers had revolted against his despotism. Nor had they permitted themselves to be regimented into Prussian uniformity by any soul-destroying excess of rehearsal. Godwin's prophetic vision of a perfectly individualistic concert was here actually realized. The noise was hair-raising. But the performers were making it with so much gusto that, in the end, I was infected by their high spirits and enjoyed the hullabaloo almost as much as they did. That concert was symptomatic of the general anarchy of post-war Italy. Those times are now past. The Fascists have come, bringing order and discipline -- even to the arts. When the Lucchesi play and sing to their Holy Face, they do it now with decorum, in a thoroughly professional and well-drilled manner. It is admirable, but dull. There are times, I must confess, when I regret the loud delirious blaring and bawling of the days of anarchy.

Almost more interesting than the official acts of worship are the unofficial, the private and individual acts. I have spent hours in the cathedral watching the crowd before the shrine. The great church is full from morning till night. Men and women, young and old, they come in their thousands, from the town, from all the country round, to gaze on the authentic image of God. And the image is dark, threatening, and sinister. In the eyes of the worshipers I often detected a certain meditative disquiet. Not unnaturally. For if the face of Providence should really and in truth be like the Holy Face, why, then -- then life is certainly no joke. Anxious to propitiate this rather appalling image of Destiny, the worshipers come pressing up to the shrine to deposit a little offering of silver or nickel and kiss the reliquary proffered to every almsgiver by the attendant priest. For two francs fifty perhaps Fate will be kind. But the Holy Face continues, unmoved, to squint inscrutable menace. Fixed by that sinister regard, and with the smell of incense in his nostrils, the darkness of the church around and above him, the most ordinary man begins to feel himself obscurely a Pascal. Metaphysical gulfs open before him. The mysteries of human destiny, of the future, of the purpose of life oppress and terrify his soul. The church is dark; but in the midst of the darkness is a little island of candlelight. Oh, comfort! But from the heart of the comforting light, incongruously jeweled, the dark face stares with squinting eyes, appalling, balefully mysterious.

But luckily, for those of us who are not Pascal, there is always a remedy. We can always turn our back on the Face, we can always leave the hollow darkness of the church. Outside, the sunlight pours down out of a flawless sky. The streets are full of people in their holiday best. At one of the gates of the city, in an open space beyond the walls, the merry-go-rounds are turning, the steam organs are playing the tunes that were popular four years ago on the other side of the Atlantic, the fat woman's drawers hang unmoving, like a huge forked pennon, in the windless air outside her booth. There is a crowd, a smell, an unceasing noise -- music and shouting, roaring of circus lions, giggling of tickled girls, squealing from the switchback of deliciously frightened girls, laughing and whistling, tooting of cardboard trumpets, cracking of guns in the rifle-range, breaking of crockery, howling of babies, all blended together to form the huge and formless sound of human happiness. Pascal was wise, but wise too consciously, with too consistent a spirituality. For him the Holy Face was always present, haunting him with its dark menace, with the mystery of its baleful eyes. And if ever, in a moment of distraction, he forgot the metaphysical horror of the world and those abysses at his feet, it was with a pang of remorse that he came again to himself, to the self of spiritual consciousness. He thought it right to be haunted, he refused to enjoy the pleasures of the created world, he liked walking among the gulfs. In his excess of conscious wisdom he was mad; for he sacrificed life to principles, to metaphysical abstractions, to the overmuch spirituality which is the negation of existence. He preferred death to life. Incomparably grosser and stupider than Pascal, almost immeasurably his inferiors, the men and women who move with shouting and laughter through the dusty heat of the fair are yet more wise than the philosopher. They are wise with the unconscious wisdom of the species, with the dumb, instinctive, physical wisdom of life itself. For it is life itself that, in the interests of living, commands them to be inconsistent. It is life itself that, having made them obscurely aware of Pascal's gulfs and horrors, bids them turn away from the baleful eyes of the Holy Face, bids them walk out of the dark, hushed, incense-smelling church into the sunlight, into the dust and whirling motion, the sweaty smell and the vast chaotic noise of the fair. It is life itself; and I, for one, have more confidence in the rightness of life than in that of any individual man, even if the man be Pascal.

Aldous Huxley (1894 – 1963) was an English writer and philosopher, widely acknowledged as one of the foremost intellectuals of his time.

AI, Bauhaus and the Case for Philosophical R&D

Molly Hankins January 13, 2026

As we begin our co-evolution with AI, questions are being raised from all sectors about the existential implications of this technological quantum leap.

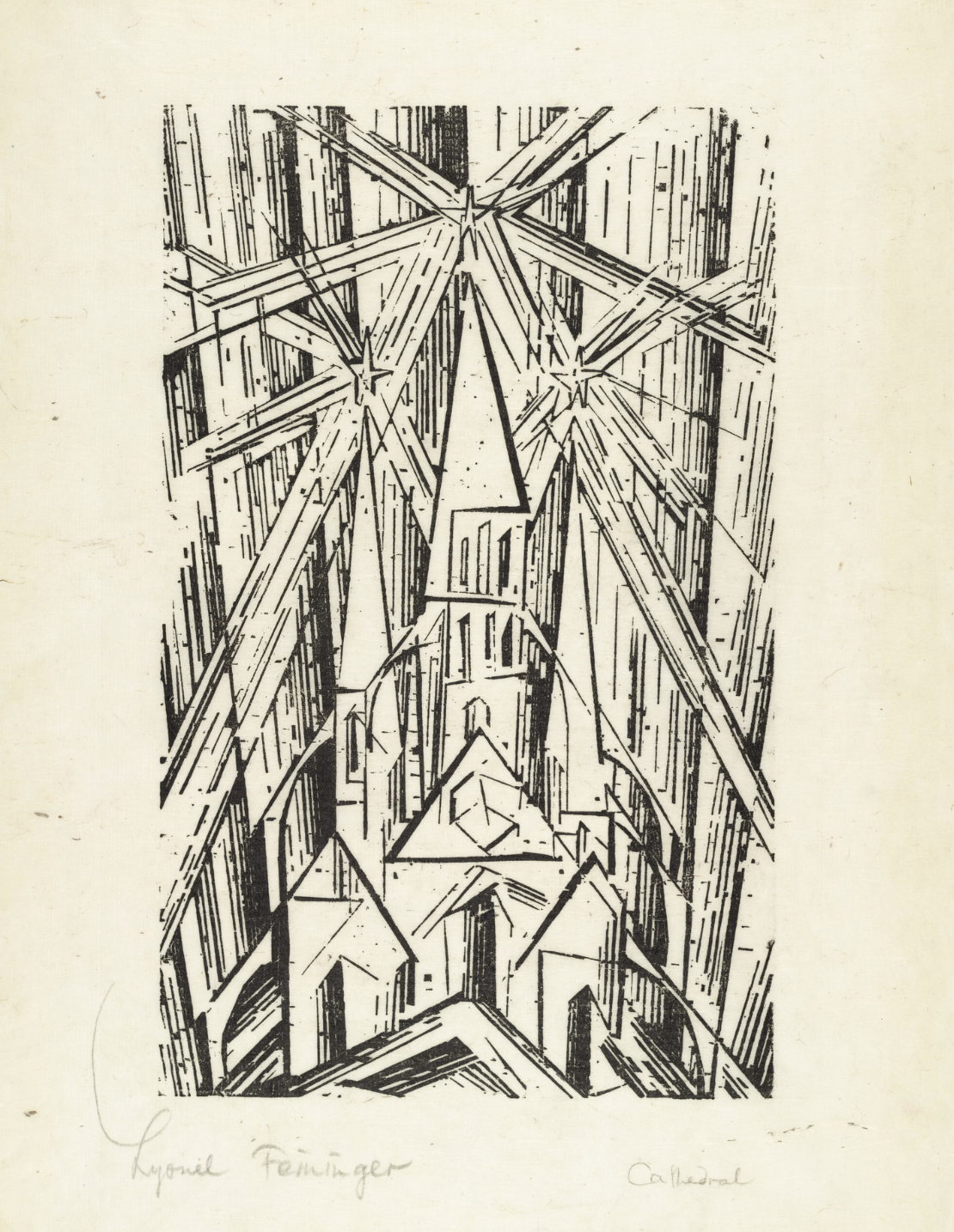

Cathedral (Kathedrale), Lyonel Feininger. 1919. Used as the cover for the Bauhaus Manifesto.

Molly Hankins January 13, 2026