MAX WEBER

For a time, Max Weber was the most exciting and most hated artist in America. Born into a Jewish family in Poland in the mid 1880s, his family emigrated to the United States where Weber grew up assimilated to Brooklyn culture, and from a young age developed a keen promise for art. Time spent in Paris, attending Gertrude Stein’s salons and taking private lessons from Matisse, gave him an insight into a new understanding of art that he brought back home. Weber became one of the very first American cubists, and a gallery show in New York brought with it a vitriolic response from the public. He was lambasted for his radical depictions, denied as brass, vulgar and offensive, and considered a disgrace. Yet, it would not be even two years before the legendary Armory show would prove that Weber was ahead of the zeitgeist, and a new wave of Modernism would sweep the country. Yet one of its founders would not be carried by the tide: Weber abandoned expressionist and cubist works and began to focus instead on figurative painting. His later work, such as the still life here, is alive with beauty and rendered expertly, but he lost his standing. He was an artist who arrived to early, and abandoned ship too soon, to ever fulfil his potential, or stake his claim.

FEDERICO CASTELLÓN

A self-taught artist and young prodigy, Catellón moved from his native Spain to Brooklyn, New York with his family at the age of seven. He was, even at this age, a gifted draughtsman and sketched relentlessly, and he spent his childhood taking advantage of the new city he lived in by visiting museums and exhibitions constantly. By the time he was a teenager, Castellón’s inspirations ranged from the Old Masters at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the burgeoning, contemporary Surrealist scene he had witnessed at small galleries. Before he had even graduated high school, he had caught the attention of Diego Rivera, who by this point was internationally acclaimed with public murals across the country. It was with Rivera’s help that Catellón travelled across Europe in his early twenties, taking in the emerging avant-garde and, on his return to New York, laid his claim as the very first American Surrealist. His etchings and sketches circulated the country and contributed to the rise of one of the most consequential movements of the century.

PABLO PICASSO

In the depths of despair and the throws of grief, Pablo Picasso created some of his most potent masterpieces. From 1901 to 1904, the Spanish artist was in what became known as his ‘Blue Period’, following the suicide of his closest friend just a year after they had moved to Paris together in search of recognition. Living in financial desolation, he began to paint with an entirely blue color scheme, rendering the world in melancholy. The Old Guitarist was painted towards the end of this period, and is more biographical than it may seem at first. The guitar player is withered and aged, his clothes torn and his body feeble and both he, and the world all around him, are depicted in nothing but various shades of blue. He rests upon his guitar, which is a shade of warm brown. This is the story of the artist and his tools, and the ability for art making to save us. In a world of sadness, the guitar is the only sign of hope - it not only supports the body of the old man as he rests upon it, but rendered in warm, earth tones it signifies to the viewer that as long as the artist can create, hope can be found. Some months later, Picasso entered a new period, one characterised by renewal and beauty in the midst of pain, but it is the Old Guitarist that offers the first signs of recovery.

GAUDENZIO FERRARI

Rising from his open tomb, Christ stands firm, looking down on us and pointing towards heaven. His burial shroud billows around him like a halo of holy light and his tenant bears the cross of St. George. It is a work of victory, commemorating Christ’s victory over death, and a testament to his place beside God. In each brushstroke is a sense of defiance and power, Ferrari considered every element of Christ’s appearance to contribute towards a sense of triumph, and to place the viewer in a lowly position. Originally the central part of an altar piece, and significant in it’s scale; seen in situ, the work would speak to the power of Christ, dwarfing the viewer below it as he rises from a mortal place of death to become a warrior of eternity.

HAROLD EDGERTON

Solid lead is heated until molten, poured through a copper sieve and allowed to fall down the length of a tower. The surface tension experienced in its decline forces the fragments into perfect spheres which are caught and called by a pool of water, and the lead shots go on to be used as projectiles for shotguns, ballasts, and shields for radiation. The process is beautiful in its simplicity, rigorously scientific in development and yet wildly raw, almost naive in its process yet to watch it with the human eye would be to see little but a wall of falling heat. It took Harold Edgerton, the man who stopped time as he became known, to demystify the process and turn it into aesthetic beauty. Edgerton developed stroboscope, and with it the entire field of high-speed photography. Where the camera had long been used as a way to capture the world around us, Edgerton used it as a scientific instrument to reveal the unseeable. Edgerton, using strobe lights and high sensitive film, turns a process that harnesses nature for violent ends into something ethereal, sublime, and deeply human.

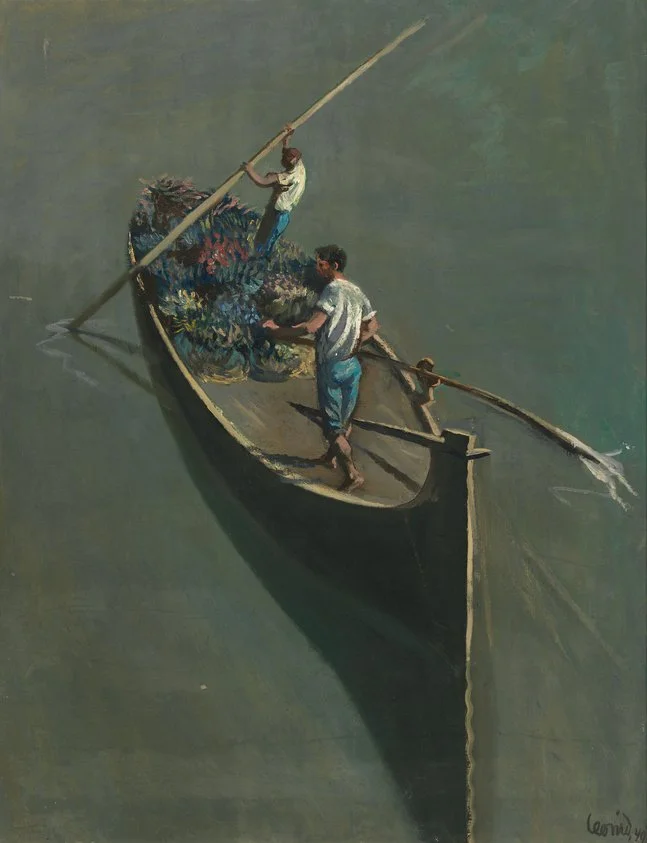

LEONID

Born into the Russian upper class at the turn of the century and dispossessed by the revolution of 1918, Leonid was unlike many of the artists he found himself rubbing shoulders with in 1920s Paris. Not just for the circumstances of his birth, which brought with it wealth and safety in a time when most artists were hailing from more humble beginnings, but in the values to politics and art that this upbringing had fostered. Leonid was part of a group known as the Neo-Romantics whose work was sharply in opposition first to the Impressionists and Cubists in Paris’ gilded age, and then to the abstract expressionist, modern American art movement of the 1950s that Leonid encountered when he moved to New York. His paintings, he believed, did not need to justify themselves with concept or theory, instead the work was inherently valuable for its beauty and the lineage of history it existed in. This work, of gondola drivers in Venice, is in all ways reminiscent of the 18th and 19th century landscapes of the city by countless romantic artists, and of the northern Italian Renaissance masters who found themselves indulging in the same subjects. Leonid, then, was not pushing boundaries or disrupting order, but he was rebelling. His paintings are overtly, almost objectively beautiful, and in a time when conceptions of beauty were fast changing, it was a rather radical act to pay homage to tradition.

RICHARD POUSETTE-DART

Creating abstraction on so monumental a scale that it obscures meaning into emotion with each approaching glance, Pousette-Dart was a founding member of the New York School of painters, poets, dancers, and musicians and one of the seminal figures of American modern art. Trained as a stone-mason and a sculptor, his work retains a physicality to it and a violence to his technique that comes with working with raw materials. The Magnificent displays this in all of its glory. From afar, it appears almost like a stain glass, shining with colour and smooth on its surface, its composition and form akin to the pleasing geometries of religious decoration. Yet as you move closer, its surface reveals itself to be scarred and haggard, thick with paint and deeply carved lines. Pousette-Dart began the piece by inscribing totemic, graphic images, inspired by the African, Oceanic, Native American, and Northwest Indian art he saw in the Natural History Museum in New York. Atop these sacred symbols, he layered thick paint so that their meanings became buried and obscured, though not destroyed. Pousette-Dart’s work rewards deep looking, it offers its treasures only to those willing to dig.

EDGAR DEGAS

Combining fragility with experimentation, Degas tried to match the mediums of depiction with the subjects themselves. From the view of the orchestra pit, our sightline obscured by the curving, almost sensual necks of the double basses, we see dancers in rehearsal. They lean and whisper, observing the prima ballerina as she stand en pointe, and we become voyeurs to unfinished artistry, and the process of alchemy through which movements of bodies becomes transformative art. To capture this, Degas used a most unusual technique. First, he created a monotype print - painting directly onto a smooth plate of glass and then transferring the image to paper through a press, creating an unrepeatable printed image. Atop the monotype, he used a fine pastel to add color, detail, and texture, the powdery medium resting atop the printed image to create a sense of ethereality that matches the dancers. The technique is wildly experimental, matching the traditional material of pastel with the rarely used, more modern monotype print to create a work that is, at every level of its creation, about the strange, magical alchemy that can happen on stage, or on paper, to produce art.

DIEGO RIVERA

Swept up by the fashions of the day, like so many artists, Diego Rivera found himself in Paris painting as a Cubist did. After years of training in his native Mexico, he travelled around Europe, taking in the avant-garde artistic movements of the day before settling in France’s capital as a young and unknown artist, befriending Amedeo Modigliani, Piet Mondrian, and Juan Gris. It would be nearly a decade before Rivera would return to Mexico, become a figurehead of the nation’s art scene, launch the Mural movement across the world and flying a flag for Central America across the art world. He would, on his return, renounce Cubism as a movement too slight and frivolous for the serious times he was living in, but before then he showed such an easy mastery of the movement, one can imagine a whole different artistic life for him. In this portrait of his then lover Marevna Vorobëv-Stebelska, he is able to capture a likeness, an essence, and play with a sense of perspective in wonderful harmony. Rivera’s talents found their apex in his large scale murals that spoke to the traditions of his country, but his early forays into more foreign movements show the breadth of his abilities and the depth of his genius.

HENRI MATISSE

In a single painting we are shown a decades worth of styles, of fears, anxieties, hopes, dreams, and fashions, and we gain insight into the process of one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. In 1909, Henri Matisse was commissioned by a wealthy Russian collector to paint two large scale works for his Moscow home. Matisse proposed three works, and the collector chose the two that went on to be known as ‘Dance II’ and ‘Music’, two of the artists most celebrated and famous works. He rejected this, ‘Bathers at the River’, and for a few years it sat unfinished, a seedling of an idea, in Matisse’s studio. Nearly 4 years later, he revisited the work, and began to update it for his new style. The loose, fluid, dancerly forms and composition that characterised ‘Dance II’ felt ill-fitting for a world at war, and he had moved on stylistically, with a deep interest in Cubism. So the work that had represent one decade, felt out of place in a new one, and Matisse made the figures more column like, more rigorous and divided, and wholly more abstract. Over the next half-decade he continued to work, refining and changing the painting, restricting the palette and distorting the figures until, almost exactly a decade after it’s initiation, he deems it finished. The final work speaks to ten years of artistic and political turmoil, and the consistence of beauty amongst it.

DIEGO VELÁZQUEZ

At the age of twelve, Diego Velázquez joined the workshop of Francisco Pacheco, a painter, sculptor, and art theorist. He saw in the young man an irrepressible talent, and spent the next six years teaching him his craft, and his theories. Velázquez spent much of his time in Pacheco’s studio painting the wooden sculptures that were commissioned by various churches and collectors across Spain, and when he left Pacheco’s tutelage at the age of 18, it is unsurprising that his paintings had remarkably sculptural qualities to them. This work, ‘The Immaculate Conception’, is one of the earliest known works by the great Spanish master, and it’s rendering of the Virgin Mary seems to place her across three dimensions. The folds of her drapery seem to be deeply carved, the clasped, praying hands emerging towards us, and her form perfectly balanced atop the moon. Velázquez is able to make her feel at once totally alive, and entirely sculptural, a fitting dialogue for the sinless mother of Christ who balances divinity and humanity upon her shoulders.

CLAUDE MONET

In the suburb of Le Havre, a wealthy suburb of Northern France, Claude Monet saw the world changing. He had grown up by the seaside, on beaches just like the one depicted here, and knew well the rural life of the areas, small towns serving locals and dominated by a thriving fishing industry. Yet as industrialism took over the nation, train services connected these once self-sustaining communities to the major cities and brought with them an influx of tourists escaping metropolis for weekends by the sea. In his depiction of Saint-Andresse, Monet captures this duality. The foreground is dominated by fishermen, their boats resting on the sand as they mill around and smoke their pipes, wearing hardy and utilitarian garb. Yet behind them, sitting on the beach, a couple look out to sea, the woman in a flowing white dress with an accent of red below here. These are the city folk, representing modernity itself that is slowly encroaching on traditional, rural life. Monet makes no moral judgement, but the work is one of quiet conflict between two types of life, learning to exist together.

MAX BECKMANN

Of all the artists despised by the Nazi Party in 1930s, Max Beckmann was amongst the most reviled. After the First World War, a boom of intellectualism occurred in Germany, with Berlin as its centre point, and the city became a fertile breeding ground for a new avant-garde that questioned the order of things before. Artists, writers, dancers, performers, musicians, and designers contributed to a culture of the Weimar Republic that was free, wild, and radical at every stage. As Hitler rose to power, he saw these movements as being in direct opposition to his philosophies, decrying it as degenerate art. Book burnings of works of Jewish intellectuals and modernist writers occurred, and the seizing of experimental, expressive, and modern work took place in galleries across the country. Beckmann became a figure head of all that Hitler saw as wrong with the creative culture of the nation, and the artist had to flee the country. This self portrait was his last painted in his home country, and it serves as a defiant declaration of his brilliance, in both skill and composition. He stand atop a staircase, elegantly dressed in a tuxedo, his eyes glancing angrily out of frame while the background behind him descends into turmoil.

LUCIEN COUTAUD

Dreamlike paintings, exploring the subconscious in beautifully rendered, immaculate detail; Lucien Coutaud had all of the trappings of surrealism and yet never identified with the group. As a young man in 1920s Paris, he found himself at the heart of a the avant-garde, forging friendships with Surrealist founder Andre Breton, fellow artist Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, and Max Ernst, and writers Paul Eluard and Jean-Paul Satre. Were it not for his constant refusal of the label, anyone would be forgiven for thinking that Coutaud was as much as surrealist as Dali or Magritte. Instead, he called his style ‘Eroticomagie’, translating simply as Erotic Magic. This is a fitting description, for in almost all of his paintings there exists an underlying sensuality. Dreamlike, fairy-tale lands and impossible worlds have this strange duality when pictured with Coutaud’s brush - a sombreness pervades atop a sexually charged energy. Inspired, perhaps, by the fledgling psychoanalytical movement, his paintings seem to marry the two human drives of sex and death in soft blues and beautiful greys.

ROBERT BRACKMAN

Regarded in his time as a master of portraiture and one of the finest art teachers in the country, Robert Brackman was a quintessential working artist. Technically gifted, good natured, and able to render not just the physical attributes of subjects but capture something of their essence, he was well liked and regarded within the artistic community and beyond, painting portraits of notable figures from John Rockefeller to Charles Lindbergh, receiving commissions from the State Department and the military, and creating large scale paintings for the burgeoning Hollywood film industry. Yet for all his skill, Brackman lacked a clear and cohesive point of view in his art that would have allowed him to make a name outside the circle of contemporaries and clients he found himself in. Expertly and elegantly combining classicism with the more academic painting styles of the day, his work is exquisitely composed and dedicated rendered, covering not just portraiture but still life and landscape as well. Yet it pushes few boundaries, and instead feels concerned with aesthetics above all else; Brackman’s training and skill removed novelty from his work which was, in many ways, his downfall.

EDOUARD VUILLARD

An artwork about looking at art, and encouraging us to value that experience. Painted from a low vantage point, Vuillard puts us directly in the gallery and at eye level with the other patrons. The painting is unusually matte, thanks to a specially formulated distemper and an unvarnished canvas. All of this contributes to a sense of accessibility, removing the museum from he pedestal and instead inviting us in to a place that feels welcoming and un-intimidating. Painted in the wake of the First World War, the work serves as an ode to museums, to the importance of and necessity for a space to engage with the past so as to remind us of our humanity. One of four works painted of Vuillard’s favourite galleries at The Louvre in Paris, each in its own way speaks to the simple, revolutionary act of looking at art, and the importance of preservation and engagement in a time of destruction.

FRANK STELLA

"After all the aim of art is to create space”, said Frank Stella, “Space that is not compromised by decoration or illustration, space within which the subjects of painting can live" In the 1970s, Stella’s work was becoming, almost accidentally, more baroque, extravagant and figurative than the minimalist work he had begun with. In the light of these newfound flourishes, Stella returned to the simplest format, centering himself in the simplicity which encapsulated his philosophy. "The concentric square format is about as neutral and as simple as you can get," he said. "It's just a powerful pictorial image. It's so good that you can use it, abuse it, and even work against it to the point of ignoring it. It has a strength that's almost indestructible - at least for me.” When he was making work that was trying to say too much, it was a return to the indestructible simple that helped him rediscover his purpose.

LÉON BONNAT

A Frenchman with Spanish influences who stripped away surface beauty to find the pain, humanity, and truth in his subjects, Léon Bonnet was revered by his contemporaries but existed in an uncomfortable middle ground between movements that stagnated his wider acclaim. Bonnat had the technical ability of the academic painters who were in vogue in late 19th century Paris, yet he emphasised feeling and overall effect rather than high attention to detail much like the impressionists who were making waves and breaking boundaries. As a result, he never quite fit into either group, and gallerists and collectors struggled to place his work. He made his living painting portraits of celebrities of the day, though both contemporary and modern critics agreed that his genius was most readily found in his religious paintings. ‘Christ on the Cross’ is one of the most known and loved crucifixion paintings of the western world. Rendering Christ with exacting brushstrokes, allowing the brutality of crucifixion and the pain of his humanness to wash over the viewer, it both allows the viewer compassion and insight, while retaining respect and glory for Christ himself.

PIERRE-AUGUSTE RENOIR

Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Aline Charigot had only just begun living together when he painted this portrait of her. Some eighteen years his junior, she had been a seamstress who modelled for the great painter before their romance began, and though he named this painting after the house plant she looks at, we can understand it as a declaration of domestic bliss. With jewel like colors and loose, fluid brushwork, it is the work of a painter totally at ease, both of his mastery of the medium and of his life in general. Charigot’s dress falls provocatively off her shoulder, yet the painting is not erotically charged, instead it is quiet, gentle, and content. The room is imperfect, with flowers laid down atop a credenza awaiting their vase and the table unkept - it is wholly lived in, and comfortable. Charigot is depicted unaware, gazing off to admire the flora ahead of her, we are given a glimpse into the interior life of the couple, our presence unnoticed, or at least unacknowledged.

HEDDA STERNE

The painting moves between figuration and abstraction with each look as if playing a trick on the eyes. In the lower half, the unmistakeable form of the Brooklyn Bridge comes in and out of focus, the lattice ironwork contorts in impossible, Escher-esque movement, and out of rigid design comes a breathing, living thing that confronts the viewer. The upper half of the painting has less to hold on to, a grey haze covers faint geometry that suggests a skyline rising behind the bridge. Hedda Sterne was a leading Abstract Expressionist, one of the few women in a male-dominated movement, and evident here is her mastery and subversion of the style. Rather than seeking pure emotion through form, she allows figuration to take on the feeling of the unconscious - the oppression and beauty of dense urbanity exists in the interior and exterior lives of all city dwellers and the duality is potently clear here. The work too exists across times, an homage to cityscapes and landscapes before her, and a declaration of a bold, intimidating future that is less readable than ever.

DEBORAH WILLIAMS REMINGTON

Born to a storied American family and descended from Frederic Remington who’s genre paintings helped define the public imagination of the wild west, Deborah Williams Remington played a quiet part in her own revolution. As a member of the burgeoning San Franciscan beat scene in the early 1950s, she was part of a group of six artists who opened the ‘Six Gallery’. In 1955 they hosted Allen Ginsberg for his first ever poetry reading, performing an early version of ‘Howl’ to small crowd. Remington was the only woman in the small group of organisers, and the event she had planned kicked off the Beat Movement across America, but quickly wrote her out of the story. Leaving the machismo of 50s literary San Francisco, she travelled across Asia, learning traditional calligraphy in Japan and absorbing color theory in India. She settled in New York on her return and became a leading ‘hard edge’ abstract painter, rebelling against the painterly forms of the abstract expressionists and instead finding beauty in rigid, almost mechanical formulations. The composition of her pieces is at once confrontational and gentle, speaking to a life of fighting against, of finding her own path, pushing up against darkness and answering with beauty and light.

HENRI MATISSE

After a lifetime of painting, Matisse would abandon the medium in his final decade to work with paper cutouts. These, he felt, could bring his philosophy and fascination with form and motif to their most simple, elegant conclusion. This painting of his favourite model, Lydia Delectorskaya who would become his studio manager, muse, and caregiver, is one of the last he did before this transition. It encapsulates so much of his decades long career, hitting all of the notes of his greatest hits as if he was aware that it would serve, in parts, as a goodbye to the medium that had served him so well. The very floor that Lydia sits upon is akin to the paper cut-outs that would follow; sharp, rigid, geometry frames the loose, natural figure of her human form while the lines and colors move from bright and thin to dark and bold. It is a work of juxtapositions, sharp edges meeting soft curves, deep blacks in symphony with soft pinks, and, in a knowing nod, the subject is surrounded by earlier Matisse works still resting on their canvases. It is, in this way, not so much a portrait of Lydia as it is of Matisse’s studio, a way to capture his lifestyle before he changed it again, as he did so many times in his wild and storied career.

ANTON MAUVE

Artists strive to capture different things. Form, color, emotion, the impression of a place - each new movement that comes searches for something different, places importance on elements hereto under explored. A group of Dutch painters in the late 19th century, known as the Hague school, were concerned above all with the mood of a scene. Accuracy, feeling, form, these were secondary characteristics in their mind. Unlike the impressionists, working at a similar time, who wanted to capture the impression of a place, in loose feeling and memory hazed depiction, the Hague School wanted to explore the pervading emotion not of the painter but of the environment in totality. Here, Anton Mauve, the de-facto leader of the group, captures a sombreness, a moody atmosphere heavy with the morose, not defeatist but quiet and weary. He creates poetry with his shades of grey that seem to hang over every element of the scene. It is not so much a portrait of a landscape, and a portrait of the weight that sits heavy on us all.

MORRIS LOUIS

Paintings in motion, concerned with themselves. Morris Louis was working in the time of abstract expressionism and was himself a leading figure in the movement of ‘color-field’ painting, making bold, gestural works that were as much about the process of their creation as anything else. Using the newly developed acrylic paints and watering them down into a fluid, viscose liquid, he would pour the mixtures from the top of the canvas and allow them to create a waterfall of colour as gravity pulled them to the bottom. Louis did not prime his canvases, meaning the raw fabric would entirely absorb the paints on its surface, staining and penetrating until the paint and the canvas unified into a single entity. This work is from his ‘Veil’ series, and while at first glance it looks like a work of darkness, with a single, organic block of blackness consuming the majority of the square, it reveals a world of process on closer inspection. At the top of the canvas you can see the huge variety of colours that were poured down, and how with each new color added it combined into a dark monolith with none of the vividness that was possible when it existed individually.

ANDREA DI BARTOLO

In brilliance and brightness, the tragedy and drama of the crucifixion is played out. The technicolor masses that gather below the cross exist in vignettes of action - Mary collapses and is looked after by saintly figures, three wise men gather below Christ to confer, guards gamble in the foreground for the punished’s belonging, and a watchmen breaks the leg of the crucified man to Christ’s left. The moral theatre is rendered in unusually joyful color such that each figure seems like a gemstone, bringing the weight of the picture to the base and leaving the top half adrift in rich gold. The Bartolo family of which Andrea was a part had a long lineage as artists and craftspeople, and the ornate decoration of gold backgrounds had become a calling card for the lineage. The haloes of Christ and the angels around him are punched with delicate geometric patterns into the wood itself, and the gold background has a border of subtly decorated relief running its length. While the bright colors of below may immediately draw the eye, it is Christ, the gold sky behind him, and the angels around him who Bartolo has paid the most attention to.

THOMAS DE KEYSER

In a time before mass produced imagery, a painting served as both aesthetic form and, often, advertising. When Thomas de Keyser was commissioned by the guild of Goldsmiths, responsible for ensuring the quality of raw material and products of the cities metal workers, there were certain requirements that the portrait had to meet. It was to be hung in the guildhall, and immediately visible to all customers and members, often as a first impression. It’s purpose then was to communicate immediately and effectively the authority, professionalism, and trustworthiness of the syndics who ran the guild. Set against a black background, and with each subject staring directly at the viewer, the work is an invitation towards them, the open hand of the seated man almost ushering us further into the building. The men clasp various tools of the trade, signalling a practiced knowledge of their work, and are depicted from a slightly lowered angle to emphasise their authority. Yet for all of its utility, it remains a most beautiful work, delicately rendered and dramatically composed. Its function does not overpower, no undermine, its aesthetic value.

JEAN-BAPTISTE LE PRINCE

A whole story is told in a single frame, a narrative unfolds through clues that deepen with each further look. A woman reclines in anything but calm, her nightdress dishevelled and open to reveal her skin underneath. A dog jumps in excitement out of frame, as if excited to see a familiar face unknown to the viewer. Two cups and a cafetière sit on the table, but only one figure exists in the scene. A chair lies tipped on the ground as if knocked over in a hasty retreat. Le Prince titilates us with every element of this painting, giving us just enough information to piece together a narrative but never so much as to be confident in our version of the story. We know an interruption has occurred, though not by who. We can assume a male suitor who was not meant to be in the boudoir of the central character has recently left the scene, just as another, more familiar to her, has entered. It is intriguing and amusing in equal measure, and an extraordinary example of Boudoir Paintings that were popular at this time. Giving the viewer a glimpse behind the curtain into the private lives of women, these paintings were playful in nature but radical in their free depictions of sexuality and the lack of shame or judgement associated with it.

GEORGE TOOKER

Tooker told stories of anxiety. He became, and remains, known for paintings of claustrophobic urbanity, cubicled domestic life, and labyrinthine liminal spaces populated by the seemingly trapped city dweller. His images are often surreal, always disquieting, and filled with a profoundly modern sense of dread. Save, that is, for Meadow I. Painted in the aftermath of his mother’s death when the painter was racked with grief and loneliness, he moved his visual language out of the metropolitan and into the pastoral. The work speaks directly to Renaissance religious works, not only in the parallel he draws between himself and his mother to Joseph and Mary weeping at the crucifixion of Christ but also in the very medium itself. Using a 17th century technique of egg tempera, he painstakingly applied fast drying homemade paint over months to create a scene of misery and calm. Painting became, in this instance, a process of grieving for Tooker - a respite from his pain that existed not only in his self but in the paintings he normally produced were replaced with a meditation of rural beauty.

GIOVANNI DOMENICO TIEPOLO

In 18th century Venice, the Rococo style reigned supreme. Characterised by lively figures and bright colors, the images of this movement are rich in adornment and decoration that seems indulgently joyful at every step. They adorned the walls and ceilings of churches, palazzos, and government buildings across the city, and there was no artist more associated with and celebrated for this style than Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. One of the last old masters of Italy, his work helped define the end of the Renaissance in his native city and far across Europe. His shadow was long across the art world at this time, and particularly so for his son Giovanni Domenico who followed in his footsteps, having trained first as his apprentice. The young Tiepolo worked in his father’s studio, and executed this painting after a series that that the elder Tiepolo had completed years earlier. Giovanni Domenico first turned his father’s series into etchings that were sold and disseminated across the country for financial gain, and then painted works based on the etchings of the originals, making this work a copy of a copy.

SIMON GROUVENEUR

Simon Grouveneur’s paintings are ciphers. Dense labyrinths of mythological symbolism, they are heavily encoded visual matrices of numbers, patterns, colors, and icons. Throughout his life he obsessively examined structures of philosophy, linguistics and mysticism and built a personal language and grammar of symbols, using his paintings to seek a truth and express complex ideas in aesthetic and balanced beauty. As obsessive as he was in his search for knowledge, he was more so in the process of creating the works. He created his paints by hand and spent months on each small canvas, working with an exacting and rigorous precision that left nothing to chance and no drop out of place. “Art is not to please or entertain”, he said, “art is to tell truth, not because artists are the only truth tellers but because art is the right media to tell truth.”