Footnotes to Plato (c.428-347BC)

Rafael's School of Athens, 1511.

Nicko Mroczkowski May 9, 2024

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name.

In this flourishing new culture, thinkers began to try and understand the world in a more organised way. From this, Western philosophy was born, and science came along with it. These thinkers asked themselves: what is the world made of, and how does it work? This was not a new question, most likely every culture before had asked it in some way, but what made the Ancient Greeks unique was their systematic approach. Because they also asked a secondary question, which, arguably, is still the starting point of any scientific inquiry: what is the correct way to talk about what something is?

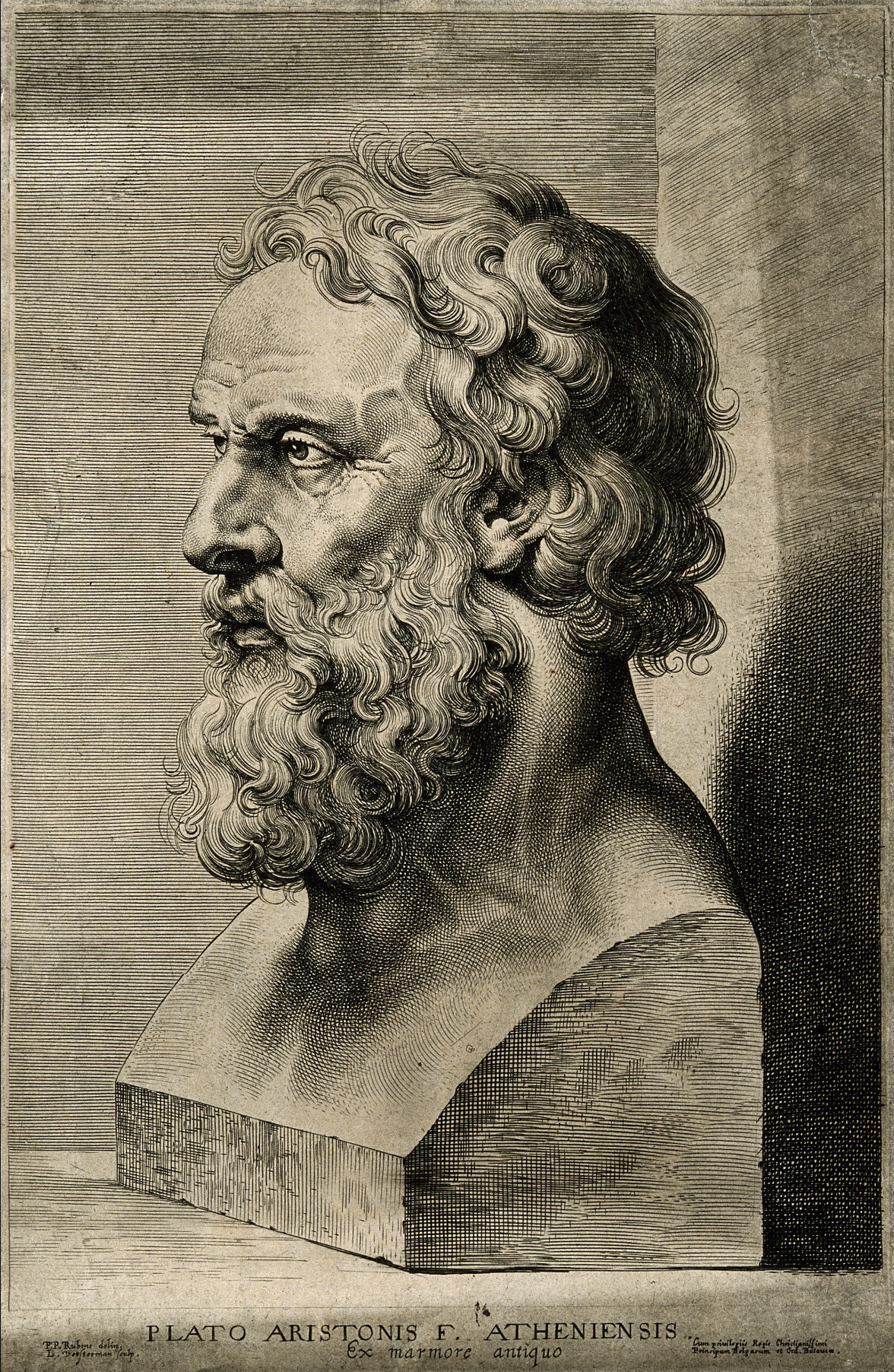

L. Vosterman, after Rubens. c. 1620.

Each of the very first philosophers answered this question with one thing: ‘substance’, or stuff. They believed that the right way to understand the world is in terms of a single type of matter, which is present in different proportions in everything that exists. Thales of Miletus, perhaps the earliest Greek philosopher, believed that all things come from water; solid matter, life, and heat are all special phases of the same liquid. For him, then, the true way to talk about an apple, for example, is as a particularly dense piece of moisture. Heraclitus, on the other hand, believed that everything is made of fire; all existence is in flux, like the dancing flame, of which an apple is a fleeting shape.

We don’t know much more about these thinkers, as not much of their work survives; most of the accounts we have are second hand. We only know for sure that each proposed a different ultimate substance that everything is made out of. Then, a little while later, along came a philosopher called Plato.

Despite its prominence, ‘Plato’ was actually a nickname meaning ‘broad’ – there is disagreement about its origin, but the most popular theory is that it comes from his time as a wrestler. His real name is thought to have been ‘Aristocles’. Whatever he was really called, Plato changed everything. Instead of arguing, like his predecessors, for a different kind of ultimate substance, he observed that substance alone is not enough to explain what exists: there is also form. In other words, he more or less invented the distinction between form and content.

One could spend a lifetime analysing these terms, and there are whole volumes of art and literary theory that address their nuances; but it’s also a common-sense distinction that we use every day. The form of something is its shape, structure, composition; the content, or substance, is the stuff it’s made of. So the form of an apple is a sweet fruit with a specific genetic profile, and its content is various hydrocarbons and trace elements. The form of a literary work is its style and composition – poetry or prose, past or present tense, first- or third-person, etc. – and its content is its subject matter, what it describes and what happens in it.

An attempt at a classification of the perfect form of a rabbit. (1915)

We can already see Plato’s influence on modern knowledge in these examples. The correct way to talk about something, for him, was primarily in terms of its form, and only secondarily in terms of its substance. This is still the case for us today. There is a powerful justification for this preference: it allows us to talk about things generally. This is basically the foundation of any science; we would get absolutely nowhere if we only analysed particular individuals. There are just too many things out there. No two animals of the same species, for example, will ever have exactly the same make-up – even if they’re clones. They have eaten different things, had different experiences; they also, quite frankly, create and shed cells so rapidly and unpredictably that differences in their substance are inevitable. What they do have in common, though, is their anatomy, behaviour, and an overall genetic profile that produces these things.

Forms are peculiar, however, because they don’t exist in the same way as substances do. While there are concrete definitions of substances, the same cannot be said for forms. There are, for example, no perfect triangles in existence, and we could probably never create one – zoom in enough, and something will always be slightly out of place. So how did Plato come up with the idea of something that can never be experienced in real life? The answer is precisely because of things like triangles. Mathematics, and especially geometry, is the original language of forms, and it can describe a perfect triangle or circle, even though one may never exist. The success of mathematical inquiries in Plato’s time allowed him to recognise that the concept of forms which worked in geometry can be applied to understand the world more generally.

Forms are perfect specimens of imperfect things, are exemplars, or things we aspire to – they are the way things ought to be, in a perfect world. ‘Form’ in Plato’s work is also sometimes translated as ‘idea’ or ‘ideal’. And so, Plato’s answer to the question of how to conduct scientific inquiry was this: the correct way to talk about something is in terms of how it should be. Despite our imperfect world, rational thinking – the capacity of the human mind for grasping things like mathematical truths – can do this, and that’s what sets human beings and their societies apart from the rest of nature.

Perfect Platonic Solids

It gets a little strange from this point on: Plato believes that forms really exist, but in a separate, perfect world. Our souls start out there and then make their way to the material world to be born, but still have implicit knowledge of their original home, and this is where reason originates. Improbable, yes, but not completely absurd. Plato was clearly trying to explain, to a society that was just beginning to understand the importance of perfect knowledge, how it could exist in our imperfect world of change and difference. Two millennia later, Kant would show that it’s due to the way the human mind is structured, but we don’t really know how this happened either.

Really, we’re still playing Plato’s game. The basic realisation that to know the world, we must study the general and the perfect, and ignore the non-essential characteristics of particular individuals – this is his legacy. Of course, this way of thinking is so deeply ingrained in Western culture that it can be hard to grapple with; it’s so fundamental that we take it for granted. But what we call knowledge today would not be possible at all without it. Seeing this, we can imagine what the influential British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead meant when he wrote that ‘the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists in a series of footnotes to Plato’.

Nicko Mroczkowski