Grasping at Gesture

Hand Catching Lead, 1968. Richard Serra.

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

In the first of these texts on gesture, I traced an unreliable and partial history of hand gestures – from roman orators and Martine Syms, to teens on TikTok and TikToks of tech bros using Apple Vision Pro – and how, somewhere along the way we lost our gestures, or lost control of them; gesticulating wildly in the open air.

Man and Matter, 1943. Leroi-Gourhan.

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

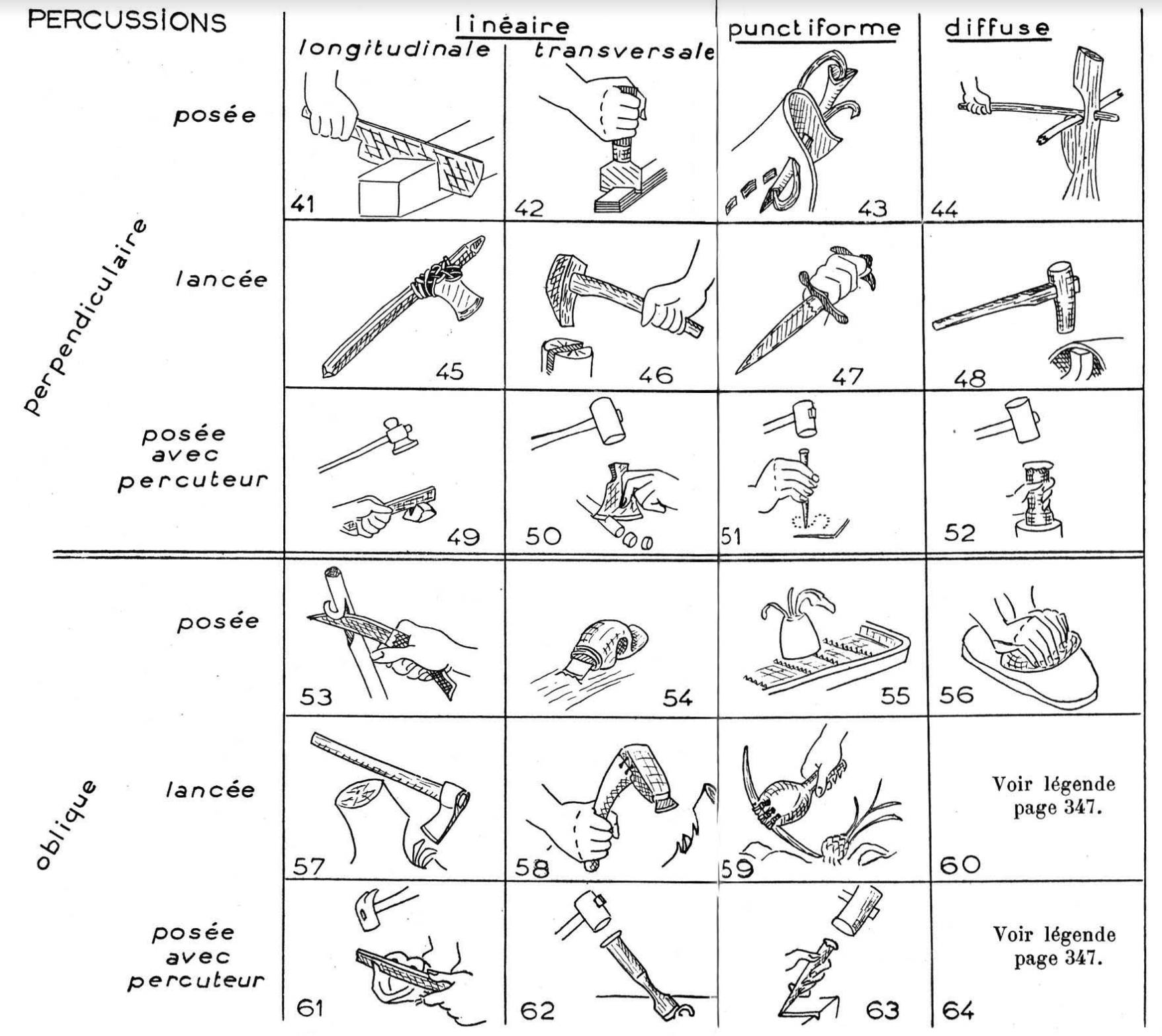

‘The essential traits of human technical gesticulation are undoubtedly connected with grasping’¹ said Andre Leroi-Gourhan in his 1965 book, Gesture and Speech. A pioneering anthropologist, Leroi-Gourhan traced evolving relationships between hands, tools, gestures, languages, and thoughts, and developed a corresponding science for such. He is associated with Structuralist school, which means that he sought out the underlying processes (or structures) that make systems meaningful. Leroi-Gourhan’s Gesture and Speech does many things: It traces a bio-cultural evolution of postures, hands, brains, tools, art and language, up to the present day; conducts cross-cultural analysis of the rhythms and organization of human society, value systems, social behavior and techno-economic apparatus; and, amidst nascent developments in robotics and early experiments in automation, speculates on the future of our species.

“Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot.”

Alcuni Monumenti del Museo Carrafa, 1778.

The book begins with a history of the human brain and hand, with Leroi-Gourhan explaining: ‘it seemed to me that the first thing to do was to measure the results of what can be done with the hand to see what [our]brains can think.’² In pursuing both brain and hand he opposed the prevailing approach in evolution studies to focus only on the ‘cerebral’. Leroi-Gourhan was interested in how thought is embodied, how it springs from material conditions.

So, what can be done with the hand? Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot; they could grip and grasp and gesture. Now grasping is not specific to humans – qualitatively, the hand that grasps remains a relatively rudimentary device that's accompanied us across many evolutionary stages – and there are a variety of types and properties of grasps. Studying the transition from instinctive to cultural uses of hands, Leroi-Gourhan observed the functional shift from the mouth to the hand, from the hand to the grasped tool, and finally the hand that operates the machine. When it comes to grasping, ‘the actions of the teeth shift to the hand, which handles the portable tool; then the tool shifts still further away, and a part of the gesture is transferred from the arm to the hand-operated machine’. This he describes as a gradual exteriorization, or ‘secretion’ of the hand-and-brain into the tool.

But gesture still somewhat eludes us, its location ambiguous. Gesture is not in and of the hand, nor in and of the tool, rather gesture is the meeting of brain, hand and tool, the driving force and thought that sets the tool to action. To bring these gestures to light, Leroi-Gourhan developed the methodology for which he is best known: the Chaîne Opératoire.

The Chaîne Opératoire, or operational chain, is a method that makes processes visible by documenting the sequence of techniques that bring things into being – be they tangible artifacts, ephemeral performances, or even the acquisition of intangible status. Leroi-Gourhan described a technique as ‘made of both gesture and tool, organized in a chain by a true syntax’. The use of ‘syntax’ here (Structuralists had a thing for linguistics) establishes a relationship between the processes and the performance of language where there is room for both shared meaning and individual flourishes. Here, gesture, like the arrangement of words in a sentence, is relational, acquiring its shape and meaning through the interaction of mind, body, tool, material and social worlds in which it participates.

This whole time thinking about grasping hands I’ve had a film in mind: Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead, in which morsels of lead fall from above, are caught, and then released by the artist's hand. Far from mechanically consistent, sometimes Serra grasps the object, sometimes he grasps at it, narrowing missing and smacking fingers to palm. From 1968 into the early 70s Serra made a series of other hand films whose subject matter are just as the titles suggest: in Hand Catching Lead a hand, of course, catches lead; in Hands Scraping (1968) two pairs of hands gather up lead shavings which have accumulated on the floor/filled the frame; in Hands Tied two tied-uphands untie themselves.

“The creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool.. can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties.”

Hands Scraping, 1968. Richard Serra.

Curator Søren Grammel said Serra’s hand works ‘demonstrate a particular action that can be applied to a material’. I suppose that’s what the Chaîne Opératoire gets at too, as well as demonstrating how the material acts on us; in Hand Catching Lead, the lead rubs off onto Serra’s blackened hands. And just as the Chaîne Opératoire observes the network of gestures that fulfill an operation, the duration of Serra’s films cosplay pragmatism, lasting as long as it takes to complete the task (however arbitrary): How many pieces of lead can you catch or not catch until you are exhausted/cramp-up/are no longer interested? How long does it take to sweep up lead shavings or untie a knot?

Serra’s Hand Catching Lead was prompted in part by being asked to document the making of House of Cards (a sculpture where four large lead sheets are propped against one another to form the sides of a cube). But a film following the making process would, he felt, be too literal and merely illustrative. Instead, Hand Catching Lead is a ‘filmic analogy’ of the creative process. Serra knew that the creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool like the Chaîne Opératoire can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties. It seems we have come up against the limits of this approach, and of Structuralism's commitment to linguistics. Returning to Agamben, who we met in the first text: ‘being-in-language is not something that could be said in sentences, the gesture is essentially always a gesture of not being able to figure something out in language; it is always a gag in the proper meaning of the term…’³ Perhaps then Serra’s grasps are gags, grasping at lead, at air and at the irrepresentable nature of being-in-gesture.

¹ Andre Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1993) [1965]), 238

² ibid.,146

³ Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000) 59

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer, researcher and editor. She is the co-founding editor of motor dance journal.