Rediscovering Living Time

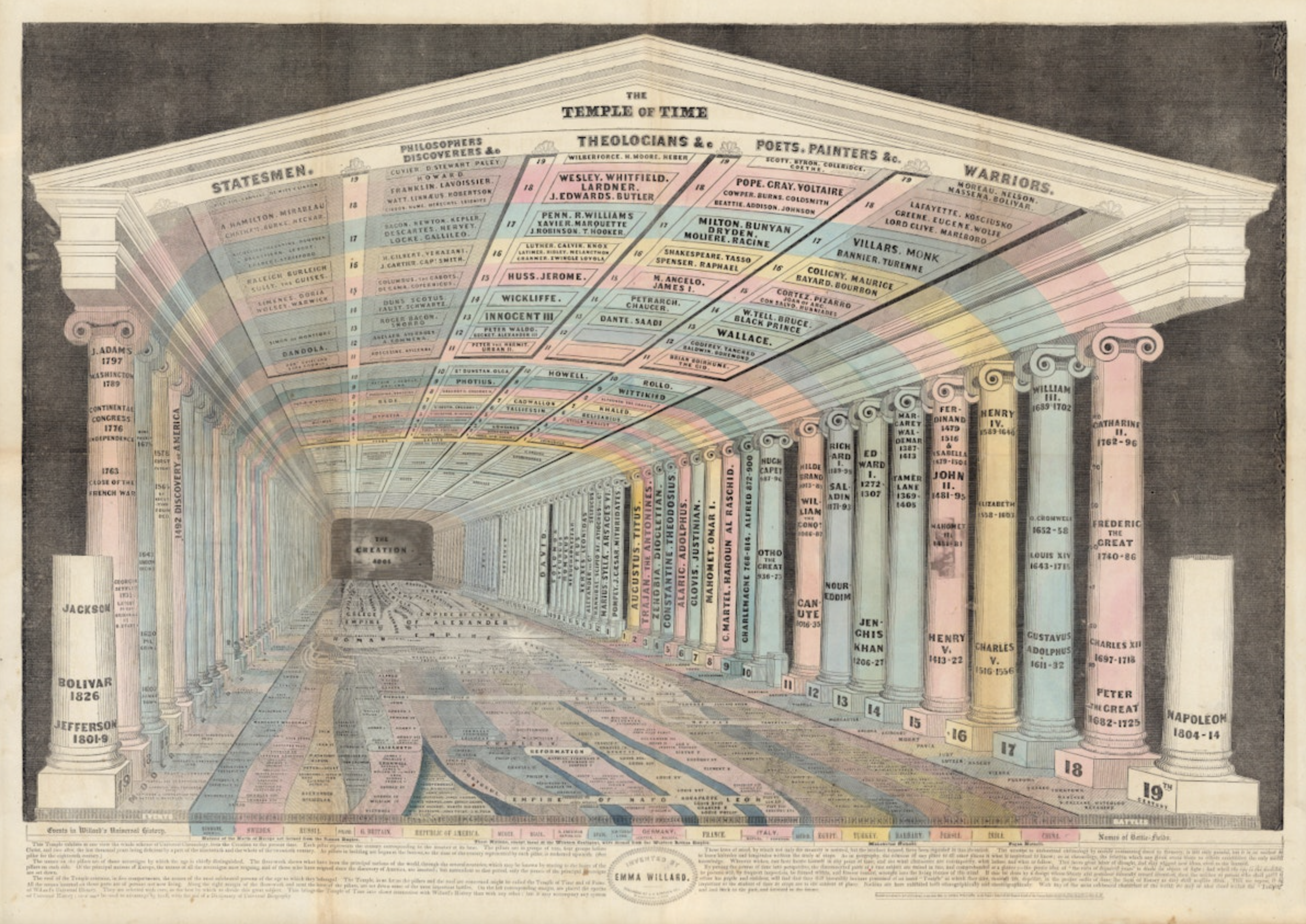

“The Temple of Time” (1846). Emma Willard.

Tuukka Toivonen September 12, 2024

Amid our species' many disagreements, the steady progression of time seems to be the one thing that everyone can agree upon and hold in common. The ticking of the clock offers a comforting backbeat to our daily comings and goings, promoting synchrony and order where there might otherwise be disorganization or chaos. Our eagerness to keep track of the passing of minutes and hours — as much through casual glances at our screens and other timepieces as intentional planning — is unmatched in its frequency by almost any other habit. There might be few moments quite as jarring as realizing one’s favored timekeeper has ground to a halt, threatening the sense of normalcy and soothing constancy afforded by clock time that our existential security seems to almost entirely rest upon. Less disorientating yet equally puzzling are the moments of flow when we become totally engrossed in soloing on the guitar, conversing with a friend or scaling up the side of a mountain, causing time as we know it to all but vanish.

Yet it is precisely these kinds of — often subtle — ruptures in one’s temporal experience that opens the door to alternative perceptions of time that can ultimately enrich our lives. Such anomalies invite active curiosity about the many mysteries and unknowns of time. Does it really progress as constantly or exist as abstractly as our attachment to machinic clock time has taught us to believe? Is time as much a co-production and outcome of life itself as it is a pace-setter? And could it be that there are cycles and makers of time that our preoccupation with the apparent precision and linearity of clock time serves to conceal? How would our lives and the way in which we partake in the more-than-human world change and expand if we explored other dimensions of time more perceptively and sensorially?

For many of us, being whisked away to a new time zone presents a type of experience that tends to fracture our sense of temporal reality quite radically — one that speaks directly to the question of how (re-)adjustment to time unfolds. We tend to normalize the sense of temporal shock by quickly adjusting our clocks to local time as soon as (or even before) we land, or by having our digital timepieces automatically adjusted for us. But our jetlagged bodies and biorhythms are not so easily persuaded, and the result is a physiological and mental sense of disorientation and fatigue at inconvenient moments. What we may not realize, however, is that the symptoms of jetlag emanate from a desynchrony of the multiple cycles we depend upon for digestion, body temperature regulation, different modes of thought, wakefulness and rest. It is therefore not the case that our acclimatization depends purely on our intentional efforts to wrestle with drowsiness — rather, it is that the complex rhythms that constitute us and the numerous symbionts we host (billions of gut microbes included) all must find a way to re-align. Restoring our “normal” sense of time and wellbeing hinges upon invisible processes through which multiple interdependent instruments — the living orchestrations of which comprise us — reach an adequate degree of synchrony and dialogue. What makes this process of readjustment truly astonishing is how it unfolds as an integrated collaboration between the vast intricacies of our biological bodies, our new environments and the way in which our home planet rotates while orbiting the sun.

As for the question of whether time marches on as precisely and exists as abstractly as we have been led to believe, exploring heliogeophysical and ecological perspectives (often neglected amid a preoccupation with physics) can help us to see a more nuanced and potent reality. First, not only do daylight hours continue to vary as the Earth travels around the sun — necessitating bodily and societal adjustments — but it actually takes the Earth slightly more than 365 days to complete one such cycle. Likewise, one rotation of the Earth on its axis does not take exactly twenty-four hours, with the Moon, earthquakes and other occurrences causing subtle fluctuations. Though imperceptible, these variations point to profound lessons about both the nature of our universe and as our own time-keeping practices and assumptions. As the historian of chronobiology and ecological restoration Mark Hall so aptly reminds us, ours is in actuality a world where “[o]rganisms do not live their lives by a metronome” but rather one where, amid constant environmental change, circadian rhythms “require continual fine-tuning” (Hall 2019, p. 385)¹. Such re-calibrations are guided by stimuli both internal and external, encompassing our solar system, our physiology as well as our social rhythms and interactions. Paradoxically enough, these multiple time-shapers that help ground our temporal experience all turn out to be far less precise and absolute than we tend to think and far more alive and idiosyncratic thanour dominant temporal cultures would imply.

“Instead of forgetting the vibrancy of living time or abandoning it in the shadow of clock time, how might you explore, and indeed celebrate, the polyphonies and polyrhythms that constitute our world and give new meaning to how time is created?”

Ecological perspectives can further enrich our understanding of time, especially if we turn to a niche group of phenologists who observe and think about the timing of diverse plant and animal species’ life-cycles. As distant as our increasingly urban and technological lives have become from the vibrant more-than-human world, most of us still retain some attachment to seasonal changes and an appreciation for their enmeshment with natural life. We intuitively realize that the appearance of swallows and other migratory birds in the Northern Hemisphere is a sign of spring (just as their return to lands in the Southern Hemisphere is taken as a sign of spring or early summer there). The blooming of certain flowers — and the simultaneous appearance of pollinators — likewise stimulates oursense of the seasons changing. The same is true of loud choruses of cicadas becoming replaced with the chirping of crickets as summer turns into autumn in places such as Japan. What phenologists have done is to bring a systematic approach to such observations of life’s cycles and developed a more refined understanding of how the rhythms of different organisms interact. For instance, flowering timings have most probably evolved with pollinators while the leaves on the same plants seem to time their cycles in relation to the herbivores that consume them. Scholars such as Bastian and Bayliss² have also brought attention to the immense value of traditional and indigenous phenological knowledges, such as calendars attuned to highly localized patterns of plant and animal life. The beauty of such calendars — that include the Japanese shi-ju-ni-ko calendar that tracks not four but forty-two seasons — is that they help bring about a sense of integration between human communities and more-than-human ecologies.

“Picture of Nations; or Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire”, (1836). Emma Willard.

In my mind, the most profound contribution of phenologists is that they show how time and its experience can be seen as collaboratively, organically constructed by multiple species, through sequences of events, interactions and degrees of synchrony. Here, the ebb and flow of life itself, its subtle orchestrations and movements, are the master time-keeper. Our mechanical timepieces and digital devices suddenly seem to offer only a vague and incomplete assessment of ‘what time it is’. Such an ecological, alternative conception of time has the power to ground our experience once again in the living world, pointing to novel possibilities for co-existence, regeneration and planetary awareness.

When we start unraveling the layers and beliefs that shape our own relationship to time, we begin to notice how entrenched notions of temporality — often linked to a need to feel productive and to conform, minute by minute, to the strictures of linear time — conceal not just how our bodies adapt to temporal disruptions and planetary movements, but an entire world of multiple times and modes of co-existence. I would now like to invite you to take a moment to reflect on how you might approach time as something that is plural, co-shaped and profoundly alive — in other words, as living time. Instead of forgetting the vibrancy of living time or abandoning it in the shadow of clock time, how might you explore, and indeed celebrate, the polyphonies and polyrhythms that constitute our world and give new meaning to how time is created? Is it possible that such an active, practical re-envisioning of time could eventually help bring more flourishing to all of the Earth’s inhabitants?

Let me leave you with a short passage from the ecological anthropologist Anna Tsing’s remarkable book, The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015), reflecting on how a full recognition of living time might allow us to generate exactly the kind of curiosity that our times require:

“Progress is a forward march, drawing other kinds of time into its rhythms. Without that driving beat, we might notice other temporal patterns. Each living thing remakes the world through seasonal pulses of growth, lifetime reproductive patterns, and geographies of expansion. Within a given species, too, there are multiple time-making projects, as organisms enlist each other and coordinate in making landscapes. The curiosity I advocate follows such multiple temporalities, revitalizing description and imagination”. (Anna Tsing 2015, p. 21.)

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.

¹ Hall, M. (2019). Chronophilia; or, Biding Time in a Solar System. Environmental Humanities, 11(2), 373–401. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-7754523

² Bastian, M., & Bayliss Hawitt, R. (2023). Multi-species, ecological and climate change temporalities: Opening a dialogue with phenology. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 6(2), 1074–1097. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486221111784