Sator Squares (Artefact III)

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 3

Location: Across Europe and the Americas.

Age: 2000 years

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies.

Sator Square in the village of Oppède le Vieux.

The “it” in question is the Sator Square. A Latin, five-line palindrome, it can be read from left or right, upwards or downwards. The earliest ones occur at Roman sites throughout the empire and by the Middle Ages, they had spread across northern Europe and were used as magical symbols to cure, prevent, and sometimes play a role in all sorts of wickedness. The one pictured here is set in the doorway of a medieval house in the semi-ruined village of Oppède le Vieux, Provence, France, carved to ward off evil spirits.

There are several different translations of the Latin, depending on how the square is read. Here is a simple version to get us started:

AREPO is taken to be a proper name, so, AREPO, SATOR (the gardener/ sower), TENET (holds), OPERA (works), ROTAS (the wheels/plow), which could come out something like ‘Arepo the gardener holds and works the wheels/plow’. Other similar translations include ‘The farmer Arepo works his wheels’ or ‘The sower Arepo guides the plow with care’.

Some academics insist that the square is read in a boustrophedon style, meaning ‘as the ox plows’, which is to say reading one line forwards and the next line backwards, as a farmer would work a field. Such a method would not only emphasize the agricultural nature of the square but also allow a more lyrical reading and could be very loosely translated thus: “as ye sow, so shall ye reap.”

“Early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stated that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.”

Sator Square with A O in chi format.

There are multiple translations and theories surrounding Sator Squares. They became the focus for intense academic debate about 150 years ago. Most of the early studies assumed that they were Christian in origin. The earliest known examples at that time appeared on 6th and 7th century Christian manuscripts and focussed on the Paternoster anagram contained within: by rearranging the letters, the Sator Square spells out Paternoster or ‘our father’, with the leftover A and O symbolizing the Alpha and the Omega.

However, in the 1920s and 30s, two Sator Squares were discovered within the ruins of Pompeii. The fatal eruption of Vesuvius that buried the city occurred in AD 79, and it is very unlikely that there were any Christians there so soon after Christ’s death. But the city did have a large Jewish community, and many contemporary scholars see the Jewish Tau symbol in the TENET cross of the palindrome, as well as other Talmudic references across the square, as proof of its Jewish origins. Pompeii’s Jews faced pogroms throughout their history, and it makes sense that they might try to hide an expression of their faith within a Roman word puzzle.

Sator Squares spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and appear in the margins of Christian manuscripts, in important treatises on magic, and in a medical book as a cure for dog-bites. Over time, they gained popularity amongst the poor as a folk remedy, even amongst those who had no knowledge of Latin or were even illiterate. (Being ignorant of meaning might increase the potency of the magic by concealing the essential gibberish of the script). In 16th century Lyon, France, a person was reportedly cured of insanity after eating three crusts of bread with the Sator Square written on them.

As the square traveled across time and country, nowhere was it used more enthusiastically than in Germany and parts of the Low Countries, where the words were etched onto wooden plates and thrown into fires to extinguish them. There are early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stating that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.

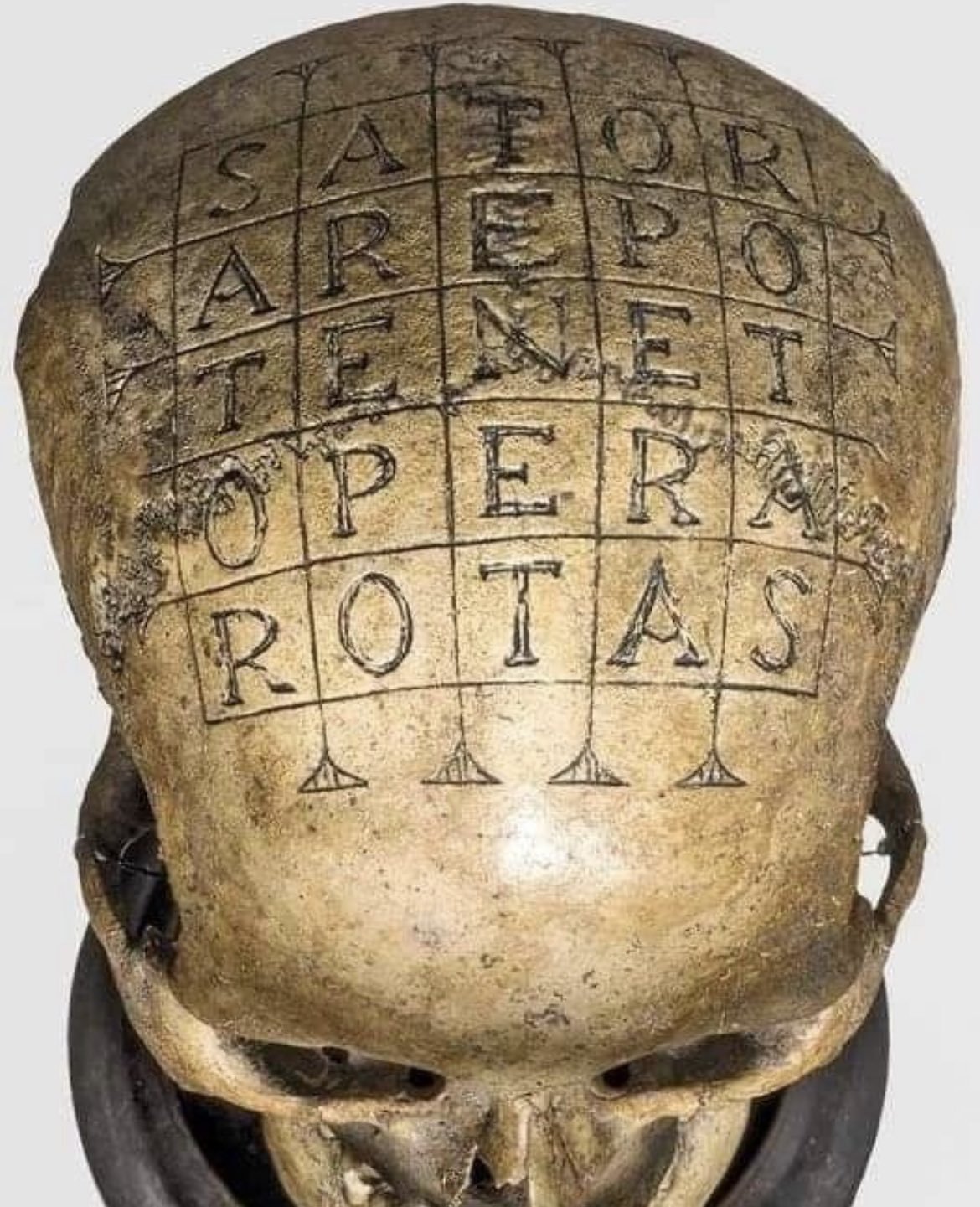

Oath Skull with Sator Square carved into bone.

From the same period comes a more sinister use of the square: The Oath Skull. Discovered in Münster in 2015 it is a human skull engraved with the Sator Square and radiocarbon dated between the 15th and 16th Centuries. It is believed to have been used by the Vedic Courts, a shadowy and ruthless court system that operated in Westphalia during that time. All proceedings of the courts were secret, even the names of judges were withheld, and death sentences were carried out by assassination or lynching. One of the few ways the accused could clear their names was by swearing an oath. Vedic courts used Oath Skulls as a means of underscoring the life-or-death nature of proceedings, and it is thought that the inclusion of the Sator Square on this skull added another level of mysticism - and the threat of eternal damnation - to the oath ritual.

When the poor of Europe headed for the New World, they took their beliefs with them. Sator Squares were used in the Americas until the late 19th century to treat snake bites, fight fires, and prevent miscarriages.

For 2000 years, interest in the Sator Squares has not waned, and a new generation has been exposed to them through the release of Christopher Nolan’s film TENET, named after the square. The film, about people who can move forwards and backwards in time, makes other references too: ‘Sator’ is the name of the arch villain played by Kenneth Branagh; ‘Arepo’ is the name of another character, a Spanish art forger whose paintings are kept in a vault protected by ‘Rotas Security’. In the film, ‘Tenet’ is the name of the intelligence agency that is fighting to keep the world from a temporal Armageddon.

Sator Squares have been described as history’s first meme. They have outlasted empires and nations, spreading across the western world and taking on newfound significance to each civilization that adopts them. Arepo should be proud of his work.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.