Pay Attention: Simone Weil (1909-1943) and the Art of Selflessness

Nicko Mroczkowski July 30, 2024

How do you live a good life? This deceptively simple question is the source of the entire Western philosophical tradition. A certain path was laid by Socrates and we’ve walked it since, yet all of its detours eventually take us back to the original mystery…

“She was the patron saint of all outsiders.” – André Gide

Nicko Mroczkowski July 30, 2024

How do you live a good life? This deceptively simple question is the source of the entire Western philosophical tradition. A certain path was laid by Socrates and we’ve walked it since, yet all of its detours eventually take us back to the original mystery.

Philosophy, of course, is also about knowledge and truth, but these things are worth little without a purpose in sight. It’s hard to admit, but not all knowledge is valuable. Consider ‘Information’, an iconic prose poem by American writer David Ignatow, which makes this point perhaps more clearly than any piece of nonfiction could. Its unnamed narrator describes the pleasure they’ve taken in counting out each of the two-million-something leaves of a particular tree. Knowledge is gained, it’s close enough to the truth, but it offers nothing.

Generous in Pardoning the Offenders, Francesco I d’Este. 1659.

The proper task of the philosopher has always been using knowledge to teach us how things should be; while the question of how they are is best left to the scientists. Simone Weil, a real philosopher’s philosopher, understood this prompt, but took things further. For her, to be a philosopher is not just to contemplate and tell us about ‘the good’, but to strive to actually be good. As she writes in her notebooks, ‘philosophy (including problems of cognition, etc.) is exclusively an affair of action and practice’.

Her unusual and tragically brief life is testament to this conviction. Born into a fairly wealthy family of professionals in Paris, she began her philosophical education at the prestigious École normale supérieure, which produced such celebrity intellectuals as Jean-Paul Sartre, Jacques Derrida, and Henri Bergson. Yet from a young age, she was notorious for refusing the comforts of her privilege and campaigning for the less fortunate. When granted a year’s sabbatical from the comfortable secondary-school teaching post that she secured after her graduation, she opted to build cars as an unskilled female (and therefore especially exploited) labourer in factories across Paris.

These episodes and tendencies are as much a part of her philosophical legacy as her ideas. When it comes to Weil, we need to look not only at what she wrote, but also what she did. Though she never actually published a full-length book, probably she was both too modest and too busy, there is no shortage of writing from Weil. Each of her texts is really the product of her experiences and the different phases that scholars sort them into – Marxism, Platonism, Christian mysticism – are also descriptions of the different periods of her personal life.

This is all pretty weird for a philosopher in the Western tradition. Many of us have discussed the relationship between theory and practice – the distinction originates in the work of Plato, the very first of the greats – but few have practised their theories to the extent that Weil does. She herself speaks of the ‘pettiness’ of the philosophers in their personal lives. Not necessarily to their discredit, but the great philosophers of the West have largely been armchair contemplators, favouring intellectual philosophical labours over manual ones.

“The best thing the individual can do is make themselves as small as possible; but also as large as all of creation.”

Not so with Weil, clearly. She believed that if, like any deep thinker, you really pay attention to something, really, you’re also already involving yourself in it. For her, to truly pay attention is to bring about a modification of one’s very being: namely, its disappearance. To be absorbed in something enough that the self fades from view. We typically associate paying attention with an active mental strain, as if our brains were squinting, as they might be in a boring lecture. Weil argues that this has it the wrong way around. It’s not so much that we’re training our focus on something, but more that we’re keeping everything else back – our desires, hang-ups, interests, and momentary emotions – in order to make space for the thing we’re attending to. And the strain we feel is the impatience to get back to our own matters. This is why she refers to attention as a ‘negative effort’, or as essentially passive. The wordplay is clearer in French: attention is attente (waiting), and paying it means anticipating, in large and small ways, the delivery of something bigger than us. When we listen carefully to a close friend, for example, are we not really setting aside our own cares and hanging out for whatever it is they want to confide in us, on their terms, which have become ours?

The Eye of God, Georgiana Houghton. 1862.

This way of thinking about attention has some consequences that are, once again, pretty strange. If attention is an emptying-out of the self, then a morality based upon it is one of radical selflessness. In contrast, Western philosophy has almost always held the individual and their freedom as the basis for any code of conduct. There are three traditional ways of establishing this foundation: thinking about how one could make oneself an outstanding person (Aristotle); thinking about the responsibilities that come with being a free individual (Kant); and thinking about how one’s actions impact the world outside them (utilitarianism).

Weil’s ethics of attention sidesteps these problems altogether. The best thing the individual can do, for her, is make themselves as small as possible; but also as large as all of creation. To live for others is her ultimate maxim. It makes sense, I think, why Weil’s life went the way it did. She saw the temptations of comfort as things that would ground her in herself. They were obstacles to, rather than opportunities for, the diversity of experiences that belongs to goodness. And she sought out this latter diversity by practising solidarity with the oppressed in every available context.

She certainly took this moral project to the extremes. She died of a heart attack at age 34. According to her biographers, she felt that she had to subject herself to the same conditions that her comrades were suffering in occupied France, having herself left for London to protect her family, and so she effectively starved herself to death. It’s difficult to say exactly whether this is an example to follow, but her compassion for others borders on the saintly. And her lesson is equally difficult to ignore: the right kind of knowledge is knowledge of others, and the right kind of life uses this knowledge to make things better for everyone.

A good life begins with paying attention to the things outside us, without cynicism, bitterness, or fear. We can’t understand who we are in the world just by thinking about ourselves. It all seems so obvious when put like this: how could we know what being good is without meeting the world we’re being good to? Like Buddha himself, we need to go out there and see for ourselves. Ironically, this kind of openness to others only strengthens our sense of the uniqueness of each individual.

This, then, is Weil’s advice. Be good: listen, lose yourself in the world, and in doing so, belong to it.

Nicko Mroczkowski

Film

<div style="padding:75.24% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/980131351?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Kagero-Za clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - June 12, 2015

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

The Ace of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel July 27, 2024

The Ace of Wands is the seed, the catalyst, and the Promethean spark that sets the suit of Wands aflame. It is the very idea of fire. Across the three decks, we have the image of a gnarled stick emanating energy…

Name: Ace of Wands

Number: 1

Astrology: Fire

Qabalah: Kether of Yod

Chris Gabriel July 27, 2024

The Ace of Wands is the seed, the catalyst, and the Promethean spark that sets the suit of Wands aflame. It is the very idea of fire. Across the three decks, we have the image of a gnarled stick emanating energy.

In Marseille, a hand comes through a ruffled portal, holding a large stick, one can see it came from a tree for twigs have been cut, and rays of energy surround it.

In Rider, a gleaming hand comes forth from a cloud, above a mountain and stream, it holds a stick still covered in leaves.

In Thoth, we have a far more vibrant image, deep reds and oranges make up this stick, with flaming Yods forming the Tree of Life. This is essentially an image of the formation of the Suit of Wands, a singular fire and its tenfold manifestations.

The Ace of Wands is a brilliant card and the first of the Minor Arcana. Fire is both the first element of the Tetragrammaton and the first divine energy. When we see this card, we should think both of a robed wizard with his magic wand, and of a matchstick, a miniature mundane wand. With a simple matchstick, one can set fire to the world.

Prometheus was a Titan in Greek mythology, his name means “Foresight”. As he foresaw the Olympian victory over the Titans, he changed sides. Though a friend to Zeus, Prometheus liked mankind. After Zeus took fire away from man as a punishment, Prometheus returned the gift of Fire by way of a stick, a hollow fennel stalk that hid the fire within it.

Man was given not simple material fire, but the very idea of conjuring it. Each stick holds the secret of fire, but only when the art of friction is applied. When we light a match, we utilize that divine gift - with wood and friction we once again create fire.

The Ace of Wands is more than a matchstick. To expand the idea more fully, we need only look down to the material body. The Wand can also be understood as the creative Phallus. Myth assures us that the divine mirrors the human, even our vulgarity: the Egyptians imagined their world had been formed by the masturbation of a lonely God, Atum.

God uses tools for the sake of creation, or at least, God is understood through symbols we are able to comprehend, and thus the body of man reflects the creative ability of the divine.

Whether the Wand in question is a phallus, an engraved ceremonial staff, or a matchstick, its goal is to manifest Fire. As the story of Prometheus shows, fire is the only element man could not conjure on his own. We are made of earth, and we shape the Earth, made of water, and our mouths bring forth spit, made of air, and we breathe it. Fire, the electric energy that gives us life, was entirely out of our control until we were given it. Fire is the vital energy.

When you pull the Ace of Wands, you are given the Promethean flame. With the tiniest spark of Will, you may manifest a brilliant fire.

Questlove Playlist

AdlnMchlle!

Archival - July Evening, 2024

Questlove has been the drummer and co-frontman for the original all-live, all-the-time Grammy Award-winning hip-hop group The Roots since 1987. Questlove is also a music history professor, a best-selling author and the Academy Award-winning director of the 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/980152301?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Flowering Trees of Hawaii"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Monuments to Gesture

Isabelle Bucklow July 25, 2024

Writing is one of those traces left behind when a hand, an instrument, and a thought meet upon, and move across, a surface. For that writing to be ‘comprehensible’ there must also converge a whole cultural system of rules and conventions which the writer and reader share – the ‘language’…

Letter (page 1), from the portfolio "Letter and Indices to 24 Songs", 1974. Hanne Darbovan.

Isabelle Bucklow July 25, 2024

“To write is to produce a mark that will constitute a sort of machine which is productive in turn, and which my future disappearance will not, in principle, hinder in its functioning”¹

Last month we looked at the gesture of grasping (a tool), and how the chaine operatoire (an anthropological tool) sought to grasp the sequence of gestures that bring something into being. Yet, gesture still slipped between our fingers, evading language and method.The gesture ‘is always a gesture of not being able to figure something out in language’, so said Agamben.² But this ‘not being able to figure out’ simultaneously contains the gesture of trying to figure out. And so if a gesture is always about figuring out, then attempts at definition and completion are futile, because gestures operate in the sphere of potentiality. If we are to inch closer to the nature of being-in-gesture, we must turn to its traces – those figurations of a once-present gesture.

Two Figures from Emersons Nature, c.1938. C.P. Cranch.

Writing is one of those traces left behind when a hand, an instrument, and a thought meet upon, and move across, a surface. For that writing to be ‘comprehensible’ there must also converge a whole cultural system of rules and conventions which the writer and reader share – the ‘language’ Agamben refers to. But even before that, before the lightness of the thought-just-thought hardens into meaning, think of Brian Eno and John Cale singing ‘up on a hill, as the day dissolves’, his ‘pencil turning moments into line.’³ These ‘lines’ could be a drawing or a song verse in cursive script, but just because those moments and thoughts have turned into line, that is not to say they have arrived at a stabilised signification: prior to being connected up to make identifiable characters and made ‘meaningful’ (by way of rules and conventions) , a line is quintessentially visual, an abstract, pure form.

Hanne Darboven (1941-2009) was a conceptual artist who, for most of her life, lived and worked in her family home in a suburb of Hamburg. Between 1966-68 she visited New York where she became good friends with Sol LeWitt and Lucy Lippard, pioneering conceptual artists and thinkers of the day. New York was where Hanne ‘tried to find something that [she] could work on for [her] whole life, it was where [she] built [her] work.’⁴ That work consisted of handwritten grids and columns of dates, equations, scripts, and transcripts; looping ‘u’s repeated then crossed out resembling lacework woven into graph paper; images and pages collected and collaged. Despite the incomprehensibility of her lines and cryptic mathematical prose, and the self-admitted fact that ‘the writing fills the space as a drawing would [and] turns out to be aesthetic’, Darboven insisted she was ‘a writer first and a visual artist second.’⁵ Her work was obsessive, ascetic, encyclopedic, machinic, and mesmeric. It is pure structure, pure gesture.

In a letter to Sol LeWitt, Hanne said of her work ‘I write but I describe nothing’. Seemingly a paradoxical endeavour, there is logic to this illogic. Writing is the act (and actualisation) of thinking, while language is the description of it. Writing need not entail expressive language, instead writing can simply reproduce writing. Clarice Lispector wrote, in her Discovering the World, ‘In order to write the only study required is the act of writing itself.’⁶ And Darboven did study the act: in the monastic tradition of the biblical scribe, she would copy passages from Goethe, Brecht, Diderot, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Gertrude Stein, Rilke, Sartre – retracing their studious concentration and hand movements line by line. As art-historian Briony Fer has observed, what Darboven embarked on was ‘a ritual re-enactment [...] of writing.’⁷ Driven to access the gesture, the activity, of writing itself..

“The act of writing is the inevitable result of my being alive”

Darboven’s Studenbuch (Book of Hours, 1991) is, as critic Donald Kusptit wrote, ‘a diary of gestures that unfurled [...] around the exhibition space.’⁸ In this sprawling work of yellow A4 pages filled with undulating ‘u’s, time – centuries of it – is experienced as monumental, and gestural, duration. Flusser reminds us ‘[the gesture of] writing is one of the ways thought becomes phenomenal’ but writing too makes time phenomenal. The ‘u’s used are the German equivalent of English ampersands: ‘and-and-and’, ad infinitum. Time and gesture flow, undifferentiated, through waves of this interconnected symbol. I summon Clarice Lispector again who wrote ‘I don’t make literature: I simply live in the passing of time.’⁹ Darboven’s ongoing ‘and-and-and’ seeks not to represent time, but mark time spent, time lived and exhaustively worked through, on and on.

R.M. Rilke - Das Studenbuch Leo Castelli, 1987. Hanne Darboven.

Marks in space and on surfaces indeed ‘mark time’, like the prophetic prisoner who inscribes tallies on the wall,or like I, in my teenage diary, who would log looks from crushes and endless days until summer holidays. The original Book of Hours similarly inscribed time onto surface, the liturgical text designating a temporal cycle of devotions and recitals across the eight canonical hours of the day. If, as Sam Lewitt surmised, ‘Darboven’s life project was to record and reconfigure the possibilities for expressing the movement of time as writing’, I’d add that her project recorded the movement of gesture in time through writing.¹⁰

Darboven’s proclivity toward copying, transcribing and repetition were not, as many have seen them, self-effacing acts of estrangement. In spending her time writing, Darboven was simultaneously writing herself into the work. In a 1989 interview with writer Isabelle Graw, Darboven explained she was ‘rewriting things by hand in order to convey [herself] through the mediation of the experience.’¹¹ The resulting work is entirely subjective, her identity being both invented and inscribed through the act of writing. ‘The act of writing’, Lispector said, ‘is the inevitable result of my being alive.’¹²

Writing is the trace of a once present gesture, a mark in space – announcing presence, thought, time – created by an action in space. The gesture of writing, a monument to moments of living.

¹ Jacques Derrida, Limited Inc (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1988), 8

² Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000) 59

³ Brian Eno and John Cale, “Spinning Away”, Wrong Way Up (Opal/Warner Bros, 1990)

⁴ Darboven quoted in Miriam Schoofs, “Hanne Darboven”, Flash Art (Online, 14th November, 2014)

⁵ Hanne Darboven and Coosje Van Bruggen, “TODAY CROSSED OUT, A PROJECT FOR ARTFORUM”, Artforum, vol. 25, no.5 (1988)

⁶ Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World, trans. by Giovanni Ponteiro (Manchester: Carcanet, 1992) 135

⁷ Briony Fer, The Infinite Line: Re-Making Art after Modernism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) 205

⁸ Donald Kuspit, “Hanne Darboven”, Artforum, vol.32, no.2 (1993)

⁹ Clarice Lispector, A Breath of Life, trans. by Johnny Lorenz (New York: New Directions, 2012) 7

¹⁰ Sam Lewitt in Stephen Hoban, Kelly Kivland, Katherine Atkins (eds.) Artists on Hanne Darboven (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 2016) 62

¹¹ See Graw in Miriam Schoofs, Joâo Fernandes (eds.),The Order of Time and Things: The Home-Studio of Hanne Darboven (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2014) 23

¹² Clarice Lispector, A Breath of Life, 7

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer, researcher and editor. She is the co-founding editor of motor dance journal.

Es Devlin

2hr 12m

7.24.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with renowned stage designer and artist Es Devlin about the difference between iteration and revelation.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/odv05sxr/widget?token=1a45928c07e8f8b637d95275cc36b04a" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/980150689?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Ivan Illich on Water and the History of the Senses 1984 (clip)"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Geometry in the Garden Pt. 3

Peter Newman July 23, 2024

A pathway is the opposite of a grid. In culture, the path is one of the most prevailing life metaphors. It is the spatialization of a story, as we move from one event to the next. Walking a path in a garden is like living in a frame within a frame, a fractal of time on a much larger journey. Like most rock gardens, time moves slower here. The sense of everything in its right place feels generous and liberating. All has been taken care of — you are free to wander…

Hanbe Garden, Mirei Shigemori 1970.

Peter Newman July 23, 2024

In the west of Japan, the Hanbe Garden is one of Shigemori’s less-known works and was completed in 1970 when he was seventy-four years old. It contains an intricately structured pathway that loops through the garden. Along the way are monoliths, inclines, vantage points, bridges, fish ponds, stepping stones, islands and a waterfall. On a plateau, some checkered paving from which a line of diagonal squares leads further.

A pathway is the opposite of a grid. In culture, the path is one of the most prevailing life metaphors. The spatialization of a story, as we move from one event to the next. Walking a path in a garden is living in a frame within a frame, a fractal of time on a much larger journey. Like most rock gardens, time moves slower here. The sense of everything in its right place feels generous and liberating. All has been taken care of — you are free to wander.

Mitaki Temple. Mirei Shigemori 1965

Shigemori created another garden a few years earlier in 1965 at the Mitaki Temple, built on a hillside on the other side of the city, not far from the centre. Among dense foliage, a two-tiered waterfall cascades down to a glade and into a pond, across which substantial stone bridges are placed. Rising from the water is a symmetrical rock triangle. Watching over the garden is a group of standing stones, like prehistoric elders. The garden is completely timeless, it feels like it could have been sleeping for a thousand years, or much longer. That it seems so is magical.

Between the Hakone Mountains and overlooking Sagami Bay, is the Enoura Observatory created by Hiroshi Sugimoto, which opened in 2017. Founded on the principle that Japanese culture is rooted in the art of living in harmony with nature, it aims to reconnect visually and mentally with the oldest of human memories. Enoura features a range of architectural styles from medieval to contemporary, much of it aligned with the movement of the sun.

There is a recreation of a ruined Roman amphitheatre, encircling a stage with the sea as a backdrop. The stage is made from optical glass supported by a wooden lattice, appearing to the audience as to be floating on water. Once a year it will be naturally illuminated from beneath, as the sun enters the glass planks which point out to sea. Close by, a narrow walkway juts out from the landscape towards the horizon, as if a springboard into the void.

Bamboo Grove. Enora Observatory. Hiroshi Sugimoto 2017

The gallery is built with Oya stone, the same textured volcanic rock used by Frank Lloyd Wright for the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. The space is 100 metres long and 100 metres above the sea. Built in line with the axis of the sun, on the summer solstice light will travel gradually across the space from one end to the other, as the day begins.

There are many wonders here. A strolling garden through the landscape, in which a bamboo grove stands in perfect contrast to the horizontal seascapes, for which the artist is famous. A cabin filled with fossils from under the sea. A tea pavilion, with an optical glass rock on which to step through the square nijiriguchi door, a feature of traditional teahouses that require visitors to crawl childlike in humility if they wish to enter. At dawn on the spring and autumn equinoxes, light shines through this door and the glass step glints in the sun.

Winter Solstice Light-Worship Tunnel. Enora Observatory. Hiroshi Sugimoto 2017

One of the most dramatic features of Enoura is the 70-metre tunnel pathway, which cuts through the ground beneath the gallery, emerging on the other side. On the winter solstice, light passes through the tunnel to illuminate a circular stone, in a ring of seating rocks. The solstice is an event celebrated by ancient cultures around the world, as a turning point in the cycle of death and rebirth. The tunnel is dark and made of steel, with a resting space lit by a light well halfway through. As you reach the other side, you come to a rectangular portal framing a view of the ocean and sky. ‘The sea, as people in ancient times would have seen it’, according to the artist. A perspective of time that naturally lends itself to reflections on mortality and the brevity of any single lifetime. ‘Yes, we disappear, but we don’t disappear into a world where there is nothing. My feeling is we return to a place where our life force is kept in storage for a while.’ says Sugimoto.

‘…she knelt down and looked along the passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw. How she longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and those cool fountains…’¹

All photography by Peter Newman.

¹ Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. 1865 Lewis Caroll.

Peter Newman is an artist. There are two permanent installations of his Skystation works in London, at Nine Elms and Canary Wharf.

Carlos Santana Playlist

Carlos Santana July 22, 2024

Carlos Santana is an American guitarist from Mexico, best known for his band Santana. Delivered with a level of passion and soul equal to the legendary sonic charge of his guitar, the sound of Carlos Santana is one of the world’s best-known musical signatures. For more than four decades Carlos has been the visionary force behind artistry that transcends musical genres and generational, cultural and geographical boundaries.

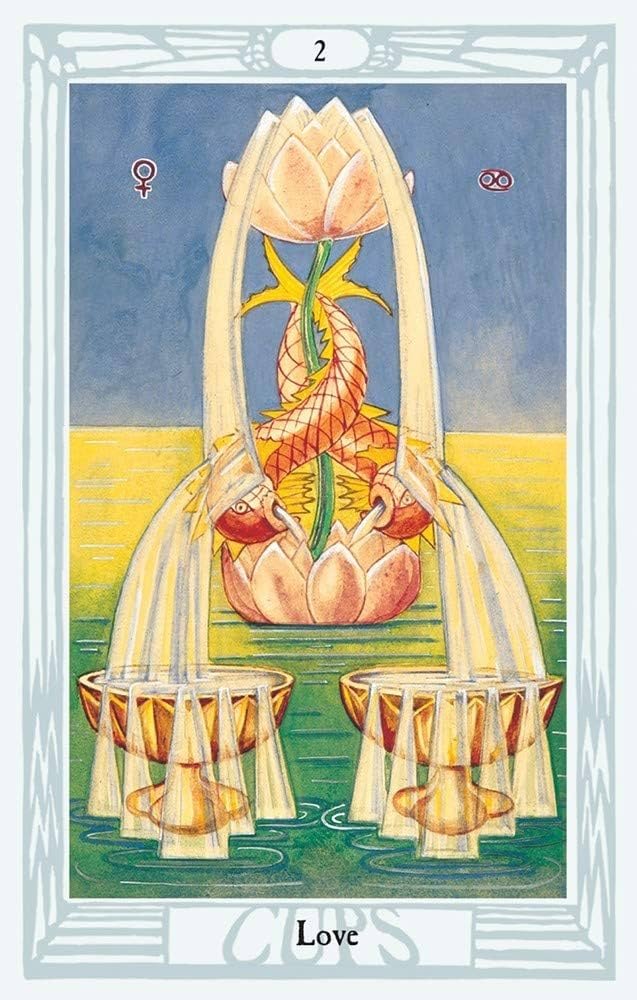

The Two of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel July 20, 2024

The Two of Cups is a card of love and the energetic union between two beings. It pertains to all matters of shared pleasure, mutual growth, and emotional experience - a human alchemy…

Name: Love, the Two of Cups

Number: 2

Astrology: Venus in Cancer

Qabalah: Chokmah of He

Chris Gabriel July 20, 2024

The Two of Cups is a card of love and the energetic union between two beings. It pertains to all matters of shared pleasure, mutual growth, and emotional experience - a human alchemy.

In Rider, we have two lovers holding their cups. Between them there is a surreal caduceus, spiralling snakes culminating in a winged lion head. The lovers are well dressed and crowned with laurels and flowers, standing in front of a pastoral scene.

In Thoth, we have two cups overflowing with water received from a lotus fountain, around which two fish are entwined. This card is Venus in Cancer, a personal, deeply intimate love. We have the greens of Venus, and the blues and amber of Cancer.

In Marseille, we have a uniquely symbolic major arcana. Here the two cups are secondary to the brilliant, alchemical scene. Underground, two angels work at an alembic containing a phoenix. Rising from this alembic, a flower sprouts another flower with fish heads as its leaves. Quite the scene! Through Qabalah, we are given the key to its name: the Queen’s Wisdom. The Queen’s Wisdom is Love.

We have many shared motifs between these cards, all of which point to the joy of love, and the energies at play within. This is when a relationship is ‘in its element’, like a fish in water.

As for the alchemical motifs, all alchemical philosophies are centered on human love as a vessel and metaphor for divine transformation. Alchemy is the Chemical Wedding, a motif we will see depicted in the Thoth deck when the Lovers VI are transmuted into one being in Art XIV.

We can see the cosmic spiralling of love directly in the work of a modern alchemist, Wilhelm Reich. A student of Sigmund Freud, Reich became increasingly far out in his vision of sexuality, moving from psychology and scientific study into mystical visions that perfectly mirror the esoteric traditions.

To Reich the sexual relationship is a product of literal spiraling cosmic energies. A motif which is clearly present in the Two of Cups.

Let us turn to the fish, present in both Marseille and Thoth. The image of a fish as related to Love calls to mind one of my favorite Grimm’s fairy tales, the Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was.

The story follows the misadventures of a boy, cast out by his father for his idiocy, and told to learn how to shudder. He finds the task quite impossible, even when faced with corpses, phantasmagorias, demons and a haunted castle. After overcoming these trials, marrying the Princess, and becoming King, he is still sad, as he can not shudder. His wife, in her wisdom, hatches a plan. It goes as follows:

“At night when the young king was sleeping, his wife was to draw the

clothes off him and empty the bucketful of cold water with the

gudgeons in it over him, so that the little fishes would sprawl about

him. Then he woke up and cried

'oh, what makes me shudder so. - What makes me shudder so, dear wife.

Ah. Now I know what it is to shudder.'

The End”

This Queen’s Wisdom is clearly that of the Two of Cups. That shuddering, as Freud knew well, is not always what one does in fear, but in love and pleasure, which the fairy tale is alluding to.

When pulling this card, we are asked to consider the union of love, forming that union, or giving energy to one we are in. To take joy in our pleasure, and to let it grow, and spring into something divine!

Hannah Peel Playlist

Archival - August 13, 2024

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Film

<div style="padding:45% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/980129923?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Grand Prix clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Sacred Geometry and White Magic

Flora Knight July 18, 2024

Sacred geometry, the concept that divine mathematical patterns underpin the universe, has profoundly influenced various religious and mystical traditions. It is rooted in the idea that God is the ultimate mathematician and that the mathematical patterns observed in nature are signs of divinity…

A detail from Hirschvogel’s ‘Geometria’ (1543).

Flora Knight July 18, 2024

Sacred geometry, the concept that divine mathematical patterns underpin the universe, has profoundly influenced various religious and mystical traditions. It is rooted in the idea that God is the ultimate mathematician and that the mathematical patterns observed in nature are signs of divinity. These sacred patterns manifest in numerous ways, such as mandalas, religious architecture, and symbols across Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism. Yet in witchcraft, it is the pentagram that has been most prevalent. Alongside its other interpretations, the pentagram embodies the principles of sacred geometry, a cohesive and balanced symbol, simple, repeatable and divine.

White Magic has long been fascinated with sacred geometry, particularly drawing inspiration from the Temple of Solomon’s design. This structure has significantly influenced the geometric architecture in witchcraft. The intricate designs and patterns seen in the Temple of Solomon have become a cornerstone for many later structures, reflecting the importance of geometry in magical practices and teachings. Various white magical institutions have adopted these geometric principles as a core part of their teachings, emphasizing the connection between spirituality and mathematics.

The caretaker at Newgrange, 1910.

One significant site that highlights the importance of sacred geometry is Bru’gh na Bo’inne, or New Grange, in Ireland. This ancient burial site, one of the oldest Western structures, dates back to ancient history and served as a burial place for Irish kings. New Grange incorporates sacred spirals in its design, which were later espoused by Fibonacci. The entrance of this structure features right-hand spirals, known as Deosil, which are used by priestesses when casting a holy circle. This counter-clockwise movement symbolizes holiness and positive energy. As one progresses through the corridors, the spirals shift to a clockwise direction, known as widdershins, which represents movement away from goodness and aligns with the sun's movement. Each chamber within New Grange symbolizes one of the three worlds of Celtic magic: the sky world, the middle world, and the underworld. This structure parallels the Temple of Solomon in its representation of the fourfold nature of the universe.

Beyond architectural marvels, sacred geometry finds its application in geomancy, a form of divination that became widespread in medieval Europe. Originating from Arabic and Persian traditions, geomancy involves interpreting patterns formed by tossing earth or stones onto the ground or making marks in the sand. By the medieval period, geomancers began using pen and ink to draw random lines of points, creating a Geomantic tableau. This method of divination became second in importance only to astrology during the Middle Ages.

Symbols of Geomancy.

In geomancy, the practitioner draws 16 lines of points while contemplating a question. These points form groups called the 'Mothers,' which generate the 'Daughters,' then the 'Nieces,' and finally the 'Witnesses and the Judge.' The Judge represents the answer to the question posed. Each figure in the Geomantic tableau is associated with a planet, zodiac sign, time of day, and element (earth, air, fire, or water). Figures that point downward are considered stable and arriving, while figures pointing upward are seen as departing and movable.

The question posed in geomancy is assigned to one of the 12 astrological houses, each governing a different aspect of life such as riches, health, marriage, and journeys. For instance, a question about marriage falls under the 'wife' house, while a query about a ship's safe passage falls under the 'journeys' house. The geomancer interprets the tableau by examining the figure in the relevant house and considering its properties to determine the outcome.

Sacred geometry's influence on witchcraft and divination is profound, reflecting the deep connection between the mystical and mathematical realms. It rejects the idea that the universe exists in chaos, and rather points to a truthful order, available for all those willing to look.

Flora Knight is an occultist and historian.

Ben Patrick

1hr 24m

7.17.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with Ben Patrick about the balance of flexibility and strength.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/et5kicki/widget?token=a6ea092cbec91477fd88ba3b49f006b0" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/980154352?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="TG3 - Our Vacation 1953 1"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Geometry in the Garden Pt. 2

Peter Newman July 16, 2024

The Japanese archipelago consists of 14,125 islands and is home to 111 volcanoes, nearly a tenth of those active in the world. Most famous of all, Mount Fuji occupies the physical, cultural and spiritual landscape with a compelling symmetrical presence. For centuries pilgrims have climbed to the summit and performed a ritual walk around the crater…

Tofuku-ji Temple, Kyoto. Mirei Shigemori 1939. (East Garden)

Peter Newman July 16, 2024

The Japanese archipelago consists of 14,125 islands and is home to 111 volcanoes, nearly a tenth of those active in the world. Most famous of all, Mount Fuji occupies the physical, cultural and spiritual landscape with a compelling symmetrical presence. For centuries pilgrims have climbed to the summit and performed a ritual walk around the crater.

The rock garden is an alternative proposition to ideas of abundance. Instead, it offers a kind of rich austerity. A metaphorical abstraction of nature, at once playful and meaningful. More akin to atmospheres of the mind and conceptually seductive. Geological time is set against the seasons or a day. Providing a space for reflection, often to be viewed from a slightly elevated Engawa platform, but not walked into. Scholars’ rocks as objects for contemplation, originated in China and aligned with an earlier Shinto veneration of stone, and the belief in its ability to attract Kami, or mythological spirits. A form of geomancy is present in the asymmetric placement of rocks and their relationship to one another. Within the confines of the garden imaginative projection and interpretation abound.

Tofuku-ji Temple, Kyoto. Mirei Shigemori 1939 (South Garden)

Mirei Shigemori (1897-1975) made two hundred and forty gardens across Japan. Although working exclusively in his home country, he collaborated with his friend Isamu Noguchi in choosing rocks for the UNESCO Garden in Paris (1958). His most famous work and his first major commission is the Zen garden at Tofuku-ji Temple in Kyoto. A fire had destroyed the main building and he was tasked with renovating the gardens. The temple couldn’t afford to pay him for his work, but he agreed on the condition of total creative freedom. “If I were to make a garden here, my work would live forever,” he said.

The garden is composed of four parts, one for each face of the central hall. As you enter, on the right are seven cylindrical rocks. The foundation stones from an earlier building, rearranged in a seemingly abstract way. As you walk further, the pattern reveals itself as the stars in the Plough or Big Dipper asterism, one of the most useful in celestial navigation. A line through the first two stars locates Polaris, the North Star.

On the left, the South Garden is inhabited by four dramatic rock clusters, representing Horai, the islands of immortals. The tallest is a dark monolith of rugged volcanic rock. These are set in an expansive sea of gravel, from which a green landscape rises in the distance, symbolizing five sacred mountains. Walking clockwise around the hall are two further gardens, more abstract still. First, a checkered pattern, in the form of clipped azalea hedges. And again, in a sweep of alternating squares of stone and moss. The pattern surfaces from a fluid green earth, before dissolving back into the ground away from you.

Tofuku-ji Temple, Kyoto. Mirei Shigemori 1939. (North Garden)

A grid is a rational mapping of space, but also invokes an idea of the infinite. A fragment cropped from a larger fabric, it suggests a world beyond the frame. An alternating grid is an interweaving of opposites, the stage on which the ancient games of Go and Chess are enacted. Grids appear in traditional craftwork, like the Ichimatsu pattern of dark and light squares, which represents prosperity and expansion. The same pattern can be found in the floors of black and white marble of grand houses in Europe. They also feature in the Renaissance perspective studies of Uccello and Leonardo. Yet the grid remains inherently modern.

‘In the cultist space of modern art, the grid serves not only as emblem but also as myth. For like all myths, it deals with paradox or contradiction.’ For artists like Mondrian and Agnes Martin, the grid is ‘a staircase to the universal’¹. They exist outside of time. By expanding in all directions, a grid defies the linearity of a narrative. An abstraction of endless choice and possibilities. No direction home.

“It’s a great game of chess that’s being played—all over the world—if this is the world at all, you know.” ²

¹ Grids. Rosalind Krauss 1979. October magazine. MIT Press

² Though the Looking Glass 1871. Lewis Carroll

Peter Newman is an artist. There are two permanent installations of his Skystation works in London, at Nine Elms and Canary Wharf.