Hannah Peel Playlist

Archival - October 17, 2024

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Five of Disks (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel November 30, 2024

In the Five of Disks, the Earth quakes and cracks, structures crumble and confusion comes. This is material instability, a crash…

Name: Worry, the Five of Disks

Number: 5

Astrology: Mars in Taurus

Qabalah: Gevurah of He

Chris Gabriel November 30, 2024

In the Five of Disks, the Earth quakes and cracks, structures crumble and confusion comes. This is material instability, a crash.

In Rider, we find two beggars enduring a snow storm. The man is lame and using crutches, his head is bandaged as he looks up in agony. The woman is barefoot, covered in a shawl and thin skirt, she looks down in defeat. They are passing a stained glass window made up of five pentacles pointing up. The material comforts enjoyed by the previous 4 figures in the suits have withdrawn, there are now distinct haves and havenots.

In Thoth, we have five cracked disks forming a downward pentagram. They bear the symbols of the five Tattvas, the magical elements that form reality. Astrologically the card is Mercury in Taurus, an unhappy position, quick and agile Mercury here is weighed down by the laborious Bull.

In Marseille, we are shown our most pleasant image, five simple coins and two flowers. Here the disruption to the stable four is seen as a growth: they are not moving up or down as in Rider and Thoth, but remain balanced. This Growth can be good, like a flower, or bad, like cancer. Qabalistically, this is the Anger of the Princess.

This card reminds me of chapter 77 of the Tao Te Ching, in which the Tao of Heaven is likened to a bow, the high is made low and the low is made high, but the Tao of Man brings the high higher and forces the low lower. The Five of Disks is an excellent expression of this.

As Mars in Taurus it raises to mind Sigmund Freud and Salvador Dali, who make excellent use of their fallen Mercury through science and art. The Parapraxis or Freudian Slip is an idea that could only arise from Mercury Taurus, the worry that our words reveal ulterior motives is exactly the kind of paranoia that flourishes in the sign.

Dali develops the “Paranoiac Critical Method” through which he follows paranoid fantasies as far as they can go. Psychoanalysis, and its town crier Surrealism, shook the very foundations of civilization by revealing their true basis in the terrifying and inhuman Unconscious.

Materially, this is a stock market crash and economic collapse, the stable power of the Four of Disks is broken. The money goes up, leaving the poor to suffer, as in Rider, or the system itself crumbles, as in Thoth.

When we pull this card, expect your comfort to be shaken, for it harkens a breaking down and collapse. Trust your suspicions. This can be a failed investment, a car crash, a break up, or a job loss but it can also be the positive risk of a new opportunity.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1029420940?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0&badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="An Optical Poem"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Walking in the City, Part 2

Michel de Certeau November 28, 2024

The Concept-city is decaying. Does that mean that the illness afflicting both the rationality that founded it and its professionals afflicts the urban populations as well? Perhaps cities are deteriorating along with the procedures that organized them. But we must be careful here. The ministers of knowledge have always assumed that the whole universe was threatened by the very changes that affected their ideologies and their positions…

Michel De Certeau was a Jesuit Priest and Scholar whose work on topics across history, sociology, philosophy, semiotics, theology and psychoanalysis helped define him as one of the most substantial and unique thinkers of his era. This essay, from his work ‘The Practice of Everyday Life’ published in 1974, is an attempt to individualize the concept of mass culture that Guy Debord and the Situationists had established a decade earlier. He finds art in the unconscious action of living, and argues that though systems are placed upon us, humans cannot and will not act as a monolith but always as individuals, employing individual tactics of expression in every facet of life.

Michel De Certeau November 28, 2024

The Concept-city is decaying. Does that mean that the illness afflicting both the rationality that founded it and its professionals afflicts the urban populations as well? Perhaps cities are deteriorating along with the procedures that organized them. But we must be careful here. The ministers of knowledge have always assumed that the whole universe was threatened by the very changes that affected their ideologies and their positions. They transmute the misfortune of their theories into theories of misfortune. When they transform their bewilderment into 'catastrophes', when they seek to enclose the people in the 'panic' of their discourses, are they once more necessarily right?

Rather than remaining within the field of a discourse that upholds its privilege by inverting its content (speaking of catastrophe and no longer of progress), one can try another path: one can analyse the microbe-like, singular and plural practices which an urbanistic system was supposed to administer or suppress, but which have outlived its decay; one can follow the swarming activity of these procedures that, far from being regulated or eliminated by panoptic administration, have reinforced themselves in a proliferating illegitimacy, developed and insinuated themselves into the networks of surveillance, and combined in accord with unreadable but stable tactics to the point of constituting everyday regulations and surreptitious creativities that are merely concealed by the frantic mechanisms and discourses of the observational organization.

This pathway could be inscribed as a consequence, but also as the reciprocal, of Foucault's analysis of the structures of power. He moved it in the direction of mechanisms and technical procedures, 'minor instrumentalities' capable, merely by their organization of 'details', of transforming a human multiplicity into a 'disciplinary' society and of managing, differentiating, classifying, and hierarchizing all deviances concerning apprenticeship, health, justice, the army or work. 'These often miniscule ruses of discipline', these 'minor but flawless' mechanisms, draw their efficacy from a relationship between procedures and the space that they redistribute in order to make an 'operator' out of it. But what spatial practices correspond, in the area where discipline is manipulated, to these apparatuses that produce a disciplinary space? In the present conjuncture, which is marked by a contradiction between the collective mode of administration and an individual mode of reappropriation, this question is no less important, if one admits that spatial practices in fact secretly structure the determining conditions of social life. I would like to follow out a few of these multiform, resistant, tricky and stubborn procedures that elude discipline without being outside the field in which it is exercised, and which should lead us to a theory of everyday practices, of lived space, of the disquieting familiarity of the city.

The Chorus of Idle Footsteps

The goddess can be recognized by her step.

Virgil, Aeneid, I, 405

Their story begins on ground level, with footsteps. They are myriad, but do not compose a series. They cannot be counted because each unit has a qualitative character: a style of tactile apprehension and kinesthetic appropriation. Their swarming mass is an innumerable collection of singularities. Their intertwined paths give their shape to spaces. They weave places together. In that respect, pedestrian movements form one of these 'real systems whose existence in fact makes up the city'. They are not localized; it is rather they that spatialize. They are no more inserted within a container than those Chinese characters speakers sketch out on their hands with their fingertips.

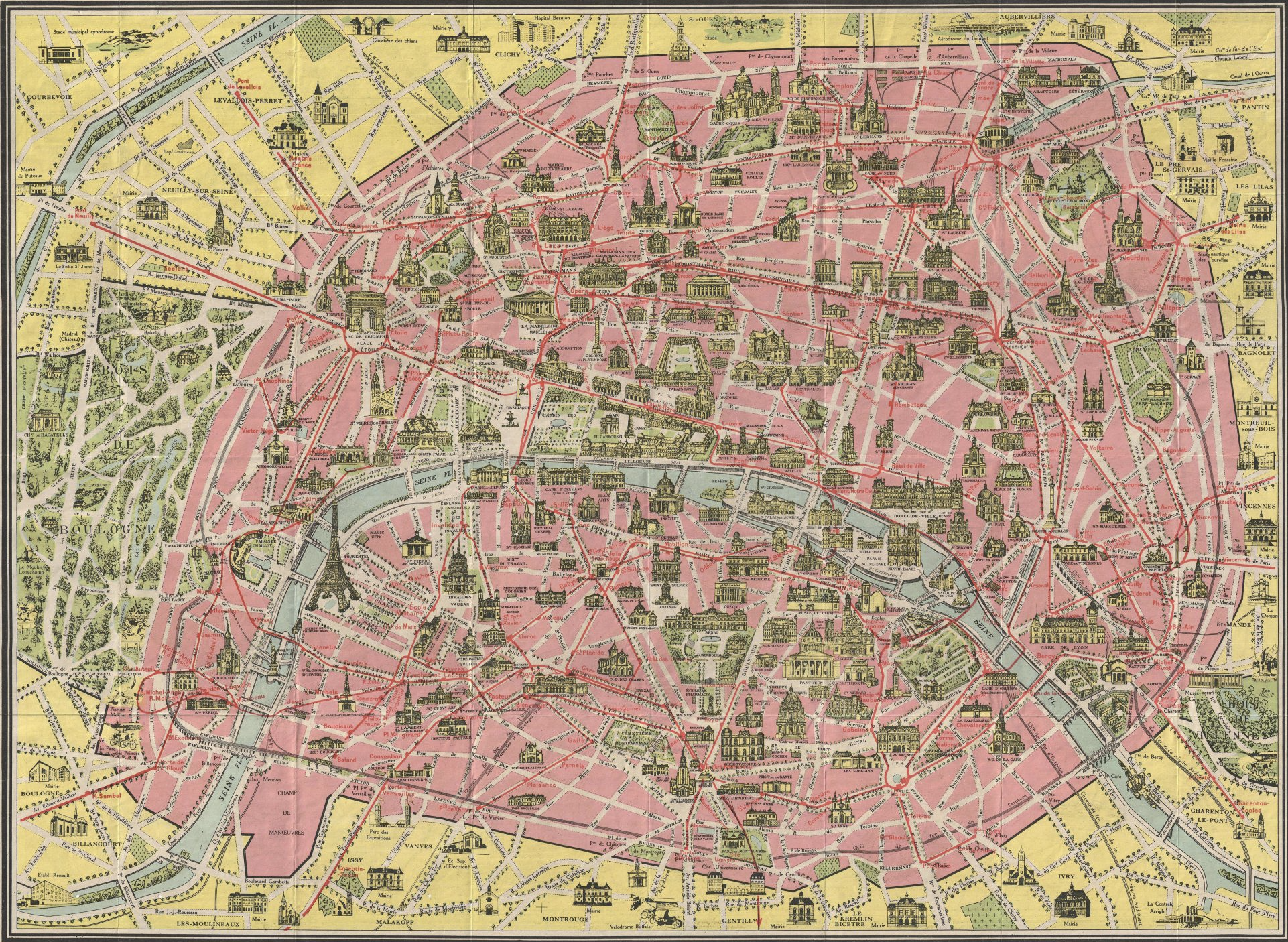

It is true that the operations of walking on can be traced on city maps in such a way as to transcribe their paths (here well-trodden, there very faint) and their trajectories (going this way and not that). But these thick or thin curves only refer, like words, to the absence of what has passed by. Surveys of routes miss what was: the act itself of passing by. The operation of walking, wandering, or 'window shopping', that is, the activity of passers-by, is transformed into points that draw a totalizing and reversible line on the map. They allow us to grasp only a relic set in the nowhen of a surface of projection. Itself visible, it has the effect of making invisible the operation that made it possible. These fixations constitute procedures for forgetting. The trace left behind is substituted for the practice. It exhibits the (voracious) property that the geographical system has of being able to transform action into legibility, but in doing so it causes a way of being in the world to be forgotten.

“Only the cave of the home remains believable, still open for a certain time to legends, still full of shadows. Except for that, according to another city-dweller, there are only 'places in which one can no longer believe in anything’.”

Walking Rhetorics

The walking of passers-by offers a series of turns (tours) and detours that can be compared to 'turns of phrase' or 'stylistic figures'. There is a rhetoric of walking. The art of 'turning' phrases finds an equivalent in an art of composing a path (toumer un parcours). Like ordinary language, this art implies and combines styles and uses. Style specifies 'a linguistic structure that manifests on the symbolic level ... an individual's fundamental way of being in the world'; it connotes a singular. Use defines the social phenomenon through which a system of communication manifests itself in actual fact; it refers to a norm. Style and use both have to do with a 'way of operating' (of speaking, walking, etc.), but style involves a peculiar processing of the symbolic, while use refers to elements of a code. They intersect to form a style of use, a way of being and a way of operating.

A friend who lives in the city of Sevres drifts, when he is in Paris, toward the rue des Saints-Peres and the rue de Sevres, even though he is going to see his mother in another part of town: these names articulate a sentence that his steps compose without his knowing it. Numbered streets and street numbers ( 112th St., or 9 rue Saint-Charles) orient the magnetic field of trajectories just as they can haunt dreams. Another friend unconsciously represses the streets whjch have names and, by this fact, transmit her - orders or identities in the same way as summonses and classifications; she goes instead along paths that have no name or signature. But her walking is thus still controlled negatively by proper names.

What is it then that they spell out? Disposed in constellations that hierarchize and semantically order the surface of the city, operating chronological arrangements and historical justifications, these words (Borrégo, Botzaris, Bougainville ... ) slowly lose, like worn coins, the value engraved on them, but their ability to signify outlives its first definition. Saint-Peres, Corentin Celton, Red Square ... these names make themselves available to the diverse meanings given them by passers-by; they detach themselves from the places they were supposed to define and serve as imaginary meeting-points on itineraries which, as metaphors, they determine for reasons that are foreign to their original value but may be recognized or not by passers-by. A strange toponymy that is detached from actual places and flies high over the city like a foggy geography of 'meanings' held in suspension, directing the physical deambulations below: Place de l'Etoile, Concorde, Poissonniere ... These constellations of names provide traffic patterns: they are stars directing itineraries. 'The Place de la Concorde does not exist,' Malaparte said, 'it is an idea.' It is much more than an 'idea'. A whole series of comparisons would be necessary to account for the magical powers proper names enjoy. They seem to be carried as emblems by the travellers they direct and simultaneously decorate.

Linking acts and footsteps, opening meanings and directions, these words operate in the name of an emptying-out and wearing-away of their primary role. They become liberated spaces that can be occupied. A rich indetermination gives them, by means of a semantic rarefaction, the function of articulating a second, poetic geography on top of the geography of the literal, forbidden or permitted meaning. They insinuate other routes into the functionalist and historical order of movement. Walking follows them: 'I fill this great empty space with a beautiful name.' People are put in motion by the remaining relics of meaning, and sometimes by their waste products, the inverted remainders of great ambitions. Things that amount to nothing, or almost nothing, symbolize and orient walkers' steps: names that have ceased precisely to be ‘proper'.

Ultimately, since proper names are already 'local authorities' or ‘superstitions', they are replaced by numbers: on the telephone, one no longer dials Opera, but 073. The same is true of the stories and legends that haunt urban space like superfluous or additional inhabitants. They are the object of a witch-hunt, by the very logic of the techno-structure. But their extermination (like the extermination of trees, forests, and hidden places in which such legends live) makes the city a 'suspended symbolic order'. The habitable city is thereby annulled. Thus, as a woman from Rouen put it, no, here 'there isn't any place special, except for my own home, that's all ... There isn't anything.' Nothing 'special': nothing that is marked, opened up by a memory or a story, signed by something or someone else. Only the cave of the home remains believable, still open for a certain time to legends, still full of shadows. Except for that, according to another city-dweller, there are only 'places in which one can no longer believe in anything’.

It is through the opportunity they offer to store up rich silences and wordless stories, or rather through their capacity to create cellars and garrets everywhere, that local legends (legenda: what is to be read, but also what can be read) permit exits, ways of going out and coming back in, and thus habitable spaces. Certainly walking about and travelling substitute for exits, for going away and coming back, which were formerly made available by a body of legends that places nowadays lack. Physical moving about has the itinerant function of yesterday's or today’s 'superstitions'. Travel (like walking) is a substitute for the legends that used to open up space to something different. What does travel ultimately produce if it is not, by a sort of reversal, 'an exploration of the deserted places of my memory’, the return to nearby exoticism by way of a detour through distant places, and the 'discovery' of relics and legends: 'fleeting visions of the French countryside’, 'fragments of music and poetry', in short, something like an 'uprooting in one’s origins' (Heidegger)? What this walking exile produces is precisely the body of legends that is currently lacking in one's own vicinity; it is a fiction, which moreover has the double characteristic, like dreams or pedestrian rhetoric, of being the effect of displacements and condensations. As a corollary, one can measure the importance of these signifying practices (to tell oneself legends) as practices that invent spaces.

From this point of view, their contents remain revelatory, and still more so is the principle that organizes them. Stories about places are makeshift things. They are composed with the world's debris. Even if the literary form and the actantial schema of 'superstitions' correspond to stable models whose structures and combinations have often been analysed over the past thirty years, the materials (all the rhetorical details of their 'manifestation') are furnished by the leftovers from nominations, taxonomies, heroic or comic predicates, etc., that is, by fragments of scattered semantic places. These heterogeneous and even contrary elements fill the homogeneous form of the story. Things extra and other ( details and excesses coming from elsewhere) insert themselves into the accepted framework, the imposed order. One thus has the very relationship between spatial practices and the constructed order. The surface of this order is everywhere punched and torn open by ellipses, drifts, and leaks of meaning: it is a sieve-order.

Michel de Certeau was a Jesuit Priest and Scholar who lived in Paris, France and contributed to innumerable fields of study. He was born in 1925 and died in 1986.

Brianna Wiest

1hr 43m

11.27.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with Brianna Wiest about the vulnerability of creating art.

<iframe width="100%" height="75" src="https://clyp.it/3rke0puv/widget?token=11975d9b523760e9719fdab1dbf59e22" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1029417897?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Timothy Leary, Bob Costas Interview clip 2"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Walking in the City, Part 1

Michel de Certeau November 26, 2024

Seeing Manhattan from the 110th floor of the World Trade Center. Beneath the haze stirred up by the winds, the urban island, a sea in the middle of the sea, lifts up the skyscrapers over Wall Street, sinks down at Greenwich, then rises again to the crests of Midtown, quietly passes over Central Park and finally undulates off into the distance beyond Harlem. A wave of verticals. Its agitation is momentarily arrested by vision…

Michel De Certeau was a Jesuit Priest and Scholar whose work on topics across history, sociology, philosophy, semiotics, theology and psychoanalysis helped define him as one of the most substantial and unique thinkers of his era. This essay, from his work ‘The Practice of Everyday Life’ published in 1974, is an attempt to individualize the concept of mass culture that Guy de Bord and the Situationists had established a decade earlier. He finds art in the unconscious action of living, and argues that though systems are placed upon us, humans cannot and will not act as a monolith but always as individuals, employing individual tactics of expression in every facet of life.

Michel De Certeau November 26, 2024

Seeing Manhattan from the 110th floor of the World Trade Center. Beneath the haze stirred up by the winds, the urban island, a sea in the middle of the sea, lifts up the skyscrapers over Wall Street, sinks down at Greenwich, then rises again to the crests of Midtown, quietly passes over Central Park and finally undulates off into the distance beyond Harlem. A wave of verticals. Its agitation is momentarily arrested by vision. The gigantic mass is immobilized before the eyes. It is transformed into a texturology in which extremes coincide - extremes of ambition and degradation, brutal oppositions of races and styles, contrasts between yesterday's buildings, already transformed into trash cans, and today's urban irruptions that block out its space. Unlike Rome, New York has never learned the art of growing old by playing on all its pasts. Its present invents itself, from hour to hour, in the act of throwing away its previous accomplishments and challenging the future. A city composed of paroxysmal places in monumental reliefs. The spectator can read in it a universe that is constantly exploding. In it are inscribed the architectural figures of the coincidatio oppositorum formerly drawn in miniatures and mystical textures. On this stage of concrete, steel and glass, cut out between two oceans (the Atlantic and the American) by a frigid body of water, the tallest letters in the world compose a gigantic rhetoric of excess in both expenditure and production.

Voyeurs or Walkers

To what erotics of knowledge does the ecstasy of reading such a cosmos belong? Having taken a voluptuous pleasure in it, I wonder what is the source of this pleasure of 'seeing the whole', of looking down on, totalizing the most immoderate of human texts.

To be lifted to the summit of the World Trade Center is to be lifted out of the city's grasp. One's body is no longer clasped by the streets that turn and return it according to an anonymous law; nor is it possessed, whether as player or played, by the rumble of so many differences and by the nervousness of New York traffic. When one goes up there, he leaves behind the mass that carries off and mixes up in itself any identity of authors or spectators. An Icarus flying above these waters, he can ignore the devices of Daedalus in mobile and endless labyrinths far below. His elevation transfigures him into a voyeur. It puts him at a distance. It transforms the bewitching world by which ·one was 'possessed' into a text that lies before one's eyes. It allows one to read it, to be a solar Eye, looking down like a god. The exaltation of a scopic and gnostic drive: the fiction of knowledge is related to this lust to be a viewpoint and nothing more.

Must one finally fall back into the dark space where crowds move back and forth, crowds that, though visible from on high, are themselves unable to see down below? An Icarian fall. On the 110th floor, a poster, sphinx-like, addresses an enigmatic message to the pedestrian who is for an instant transformed into a visionary: It's hard to be down when you're up.

The desire to see the city preceded the means of satisfying it. Medieval or Renaissance painters represented the city as seen in a perspective that no eye had yet enjoyed. This fiction already made the medieval spectator into a celestial eye. It created gods. Have things changed since technical procedures have organized an 'all-seeing power'? The totalizing eye imagined by the painters of earlier times lives on in our achievements. The same scopic drive haunts users of architectural productions by materializing today the utopia that yesterday was only painted. The 1370-foot-high tower that serves as a prow for Manhattan continues to construct the fiction that creates readers, makes the complexity of the city readable and immobilizes its opaque mobility in a transparent text.

Is the immense texturology spread out before one's eyes anything more than a representation, an optical artefact? It is the analogue of the facsimile produced, through a projection that is a way of keeping aloof, by the space planner urbanist, city planner or cartographer. The panorama-city is a 'theoretical' (that is, visual) simulacrum, in short a picture, whose condition of possibility is an oblivion and a misunderstanding of practices.

The ordinary practitioners of the city live 'down below', below the thresholds at which visibility begins. They walk - an elementary form of this experience of the city; they are walkers, Wandersmanner, whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban 'text' they write without being able to read it. These practitioners make use of spaces that cannot be seen; their knowledge of them is as blind as that of lovers in each other's arms. The paths that correspond in this intertwining, unrecognized poems in which each body is an element signed by many others, elude legibility. It is as though the practices organizing a bustling city were characterized by their blindness. The networks of these moving, intersecting writings compose a manifold story that has neither author nor spectator, shaped out of fragments of trajectories and alterations of spaces: in relation to representations, it remains daily and indefinitely other.

Escaping the imaginary totalizations produced by the eye, the everyday has a certain strangeness that does not surface, or whose surface is only its upper limit, outlining itself against the visible. Within this ensemble, I shall try to locate the practices that are foreign to the 'geometrical' or 'geographical' space of visual, panoptic, or theoretical constructions. These practices of space refer to a specific form of operations ('ways of operating'), to 'another spatiality' (an ‘anthropological', poetic and mythic experience of space), and to an opaque and blind mobility characteristic of the bustling city. A migrational, or metaphorical, city thus slips into the clear text of the planned and readable city.

“This is the way in which the Concept-city functions; a place of transformations and appropriations, the object of various kinds of interference but also a subject that is constantly enriched by new attributes, it is simultaneously the machinery and the hero of modernity.”

From the Concept of the City to Urban Practices

The World Trade Center is only the most monumental figure of Western urban development. The atopia-utopia of optical knowledge has long had the ambition of surmounting and articulating the contradictions arising from urban agglomeration. It is a question of managing a growth of human agglomeration or accumulation. ‘The city is a huge monastery', said Erasmus. Perspective vision and prospective vision constitute the twofold projection of an opaque past and an uncertain future on to a surface that can be dealt with. They inaugurate (in the sixteenth century?) the transformation of the urban fact into the concept of a city. Long before the concept itself gives rise to a particular figure of history, it assumes that this fact can be dealt with as a unity determined by an urbanistic ratio. Linking the city to the concept never makes them identical, but it plays on their progressive symbiosis: to plan a city is both to think the veiy plurality of the real and to make that way of thinking the plural effective; it is to know how to articulate it and be able to do it.

An Operational Concept?

The 'city' founded by utopian and urbanistic discourse is defined by the possibility of a threefold operation.

First, the production of its own space (un espace propre): rational organization must thus repress all the physical, mental and political pollutions that would compromise it;

Second, the substitution of a nowhen, or of a synchronic system, for the indeterminable and stubborn resistances offered by traditions; univocal scientific strategies, made possible by the flattening out of all the data in a plane projection, must replace the tactics of users who take advantage of 'opportunities' and who, through these trap-events, these lapses in visibility, reproduce the opacities of history everywhere;

Third and finally, the creation of a universal and anonymous subject which is the city itself: it gradually becomes possible to attribute to it, as to its political model, Hobbes's State, all the functions and predicates that were previously scattered and assigned to many different real subjects - groups, associations, or individuals. 'The city', like a proper name, thus provides a way of conceiving and constructing space on the basis of a finite number of stable, isolatable, and interconnected properties.

Administration is combined with a process of elimination in this place organized by 'speculative' and classificatory operations. On the one hand, there is a differentiation and redistribution of the parts and functions of the city, as a result of inversions, displacements, accumulations, etc.; on the other there is a rejection of everything that is not capable of being dealt with in this way and so constitutes the 'waste products' of a functionalist administration (abnormality, deviance, illness, death, etc.). To be sure, progress allows an increasing number of these waste products to be reintroduced into administrative circuits and transforms even deficiencies (in health, security etc.) into ways of making the networks of order denser. But in reality, it repeatedly produces effects contrary to those at which it aims: the profit system generates a loss which, in the multiple forms of wretchedness and poverty outside the system and of waste inside it, constantly turns production into ‘expenditure'. Moreover, the rationalization of the city leads to its mythification in strategic discourses, which are calculations based on the hypothesis or the necessity of its destruction in order to arrive at a final decision. Finally, the functionalist organization, by privileging progress (i.e. time), causes the condition of its own possibility - space itself - to be forgotten; space thus becomes the blind spot in a scientific and political technology. This is the way in which the Concept-city functions; a place of transformations and appropriations, the object of various kinds of interference but also a subject that is constantly enriched by new attributes, it is simultaneously the machinery and the hero of modernity.

Today, whatever the avatars of this concept may have been, we have to acknowledge that if in discourse the city serves as a totalizing and almost mythical landmark for socio-economic and political strategies, urban life increasingly permits the re-emergence of the element that the urbanistic project excluded. The language of power is in itself 'urbanizing', but the city is left prey to contradictory movements that counterbalance and combine themselves outside the reach of panoptic power. The city becomes the dominant theme in political legends, but it is no longer a field of programmed and regulated operations. Beneath the discourses that ideologize the city, the ruses and combinations of powers that have no readable identity proliferate; without points where one can take hold of them, without rational transparency, they are impossible to administer.

Michel de Certeau was a Jesuit Priest and Scholar who lived in Paris, France and contributed to innumerable fields of study. He was born in 1925 and died in 1986.

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - September 11, 2015

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

Questlove Playlist

WndyMlvn: THXGNG

Archival - November Evening 2024

Questlove has been the drummer and co-frontman for the original all-live, all-the-time Grammy Award-winning hip-hop group The Roots since 1987. Questlove is also a music history professor, a best-selling author and the Academy Award-winning director of the 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.

Ten of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel November 23, 2024

The Ten of Cups is entirely satisfied, the ooze and gunk that had dirtied the cups before has been washed away, and now clean water overflows. This is the ‘over the rainbow’ - the storm has passed and we can appreciate the beauty. This is the flow state…

Name: Satiety, the Ten of Cups

Number: 10

Astrology: Mars in Pisces

Qabalah: Malkuth of He

Chris Gabriel November 23, 2024

The Ten of Cups is entirely satisfied, the ooze and gunk that had dirtied the cups before has been washed away, and now clean water overflows. This is the ‘over the rainbow’ - the storm has passed and we can appreciate the beauty. This is the flow state.

In Rider, we find a happy family, a man and wife rejoice as they look up to a rainbow, upon which ten cups are superimposed, and a brother and sister dance for joy. A little cottage sits a ways away, and a creek runs through the yard. This image is Dorothy’s yearning dream in the Wizard of Oz, the technicolor world “heard of once in a lullaby”.

In Thoth, we have ten cups arranged as the Tree of Life. Clean water flows from the top cup downwards as a complex but perfectly functioning fountain. It sits atop a flat image of a red lotus. Astrologically this card is Mars in Pisces, where the force of war is made dreamy and psychic: the flow state.

In Marseille, we have 9 full, open cups below one large sealed cup. Qabalistically this is the Kingdom of the Queen. The Kingdom of the Queen is satiated.

The Ten of Cups is one of the most pleasant cards in tarot, alongside the Ten of Disks. While the Ten Disks are the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, this is the wonderful dreamland, the promised peace. This is the rainbow as a sign from God after the flood.

It calls to mind William Wordsworth’s poem My Heart Leaps Up:

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

As the flow state of Mars in Pisces, this card may indicate “oblique strategies”, obstacles that seemed immense will melt away through a strange solution.

When we pull this card, we may resolve lasting difficulties, find gnawing issues satisfied, or find joy in something dreamy.

Film

<div style="padding:56.21% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1029425608?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0&badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="You Can't Take It With You clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Pauli and Jung’s Synchronicity

Molly Hankins November 21, 2024

In 1945, the Viennese physicist Wolfgang Pauli won the Nobel Prize for his work on quantum numbers and the structure of matter that predicted the existence of the neutrino 20 years before it was confirmed. This was 18 years after he started seeing Carl Jung for psychotherapy and 7 years before he and Jung would publish The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche exploring in great detail the concept of ‘synchronicity.’..

Illustration from Carl Jung’s ‘Liber Novus’ or ‘The Red Book’. 1917.

Molly Hankins November 21, 2024

In 1945, the Viennese physicist Wolfgang Pauli won the Nobel Prize for his work on quantum numbers and the structure of matter that predicted the existence of the neutrino 20 years before it was confirmed. This was 18 years after he started seeing Carl Jung for psychotherapy and dream analysis following his mother’s suicide, and 7 years before he and Jung would publish The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche exploring in great detail the concept of ‘synchronicity.’ It is a word intrinsically ties to Jung, who started using it in lectures a few years after meeting Pauli and published a book of the same name a year before his death, but the idea was brought to life in their collaboration.

In The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche, synchronicity describes an acausal relationship between events that occur sequentially in linear time and appear meaningfully related but with no identifiable, underlying relationship. At the time, using physics as a lens to study metaphysics wasn’t controversial; Pauli’s friends and contemporaries like physicists Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg were working together to explore theories that would bridge understanding between esoteric philosophy, practice and science.

The same year his treatise with Jung was published, Pauli spent the summer in Copenhagen with Bohr and Heisenberg having these very conversations. Heisenberg said that physicists needed to make every effort to grasp the meaning of old religions because, “… it quite obviously refers to a crucial aspect of reality.” This was before the chokehold of post-World War II and the Cold War thought made physics-funding the exclusive business of the war machine and condemned exploration of metaphysics to the realm of taboo. Fellow Austrian physicist and Tao of Physics author Fritjof Capra famously never received institutional funding again for his research after the book was published in 1975.

“Synchronicity mirrors quantum entanglement, which occurs when two particles link together and influence each other's state no matter how far apart they are, because at the quantum level, the laws governing the interactions of space and time stop behaving according to the principle of causality.”

Like so many revolutionary minds, Pauli was troubled and controversial, known for his alcoholism and quarrelsome nature. His mother’s suicide, which followed his father’s infidelity, devastated him, but ultimately pushed him to seek out Jung while they were both living in Zurich. Their relationship continued by letter, most famously documented in their published book of letters from 1932 to 1958, Atom and Archetype, named after a Pauli quote included in the collection. “As I regard physics and psychology as complementary types of examination,”, he wrote, “I am certain that the investigation of the psyche can throw light on the structure of the atom, just as the study of the atom can illuminate the structure of the psyche.” The core tenet of this thought is that both the human psyche and atom contain a central core, “a nucleus of self” surrounded by orbiting subatomic particles or “unconscious electrons” such as archetypes or complexes that influence conscious awareness. Atomic stability depends on the arrangement of the electrons, so their analogy espoused that stability of the psyche depended on the balance between aspects of the conscious and unconscious mind.

Synchronicity was present in their daily lives too, as Pauli was known for disrupting experiments simply by being nearby. This became known to physicists as the ‘Pauli effect’ and describes the inexplicable disruption of technical equipment in the presence of certain people. When an experiment failed at University of Göttingen after a measuring device stopped working, the lab’s director James Franck wrote to Pauli joking that he could not have been the cause because he wasn’t physically present. In response Pauli revealed that he actually had been at the Göttingen rail station at the time of the failure. After a china vase fell and shattered for no discernible reason at a symposium in 1948 as he entered the meeting hall at Jung’s Institute, Pauli attempted to explain the phenomenon and its relationship to psychology in a new paper called ‘Background-Physics.’

While Pauli and Jung were never able to completely pin down the mechanism of synchronicity explored in their 30 year collaboration on the subject, they did conclude that the experience must somehow correlate to quantum entanglement. Synchronicity mirrors quantum entanglement, which occurs when two particles link together and influence each other's state no matter how far apart they are, because at the quantum level, the laws governing the interactions of space and time stop behaving according to the principle of causality.

And it makes sense that the phenomenon of synchronicity was explored and articulated by a psychologist and a physicist: the experience of it feels like a feedback loop between what’s going on in our minds and the physical world. As Jung himself said, “Synchronicity is the coming together of inner and outer events in a way that cannot be explained by cause and effect and that is meaningful to the observer.” Quantum physics tells us that to observe reality is to essentially render it, and synchronicity leaves us with the feeling our perspective is undeniably influencing the experience being rendered.

The study of the occult lies at the intersection of observation and creation of what’s rendering in the physical and how we can work with it. Synchronicity, as Terrence McKenna said, is the universe nodding at us as confirmation that we’re on the right track.

Molly Hankins is a Neophyte + Reality Hacker serving the Ministry of Quantum Existentialism and Builders of the Adytum

Bjarke Ingles (Part 1)

2hr 12m

11.20.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with architect Bjarke Ingels about the care involved in making things look effortless.

<iframe width="100%" height="75" src="https://clyp.it/4enk2hef/widget?token=c92f9b3b85052fc3b8884f7b49e2edbc" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Why Collect Digital Art? What Do You Believe? (Gen Art)

Ian Rogers November 19, 2024

On the 14th of November, I received a text message from the Digital Art Curator Grida Hyewon Jang asking if I would mind giving an answer to three questions she had posted on X. She told me she planned to use the responses in a lecture she would be delivering to art students in Korea who are not particularly familiar with digital art. “Who knows – your comments might inspire a future artist!” she wrote…

Ian Rogers November 19, 2024

On the 14th of November, I received a text message from the Digital Art Curator Grida Hyewon Jang asking if I would mind giving an answer to three questions she had posted on X. She told me she planned to use the responses in a lecture she would be delivering to art students in Korea who are not particularly familiar with digital art. “Who knows – your comments might inspire a future artist!” she wrote.

That same day I was traveling from Paris, France to Marfa, Texas, for ArtBlocks annual community gathering (for more on ArtBlocks please read my earlier Tetragrammaton piece, Chimera: The Not-so-Still Life of Mpkoz). I had many thoughts bouncing around in my head that morning regarding digital art, a medium much maligned in the aftermath of FTX yet somehow still living and gaining momentum again. Grida’s request was a welcome opportunity to put those thoughts here on digital paper. I’m very happy for the opportunity to save these thoughts for posterity and present them to you, dear Tetragrammaton reader.I welcome your feedback and discussion.

“Basquiat's work increases in value because the number of people who know the story increases while the supply does not. Luxury brands are trading on heritage and storytelling, not only products. Similarly, if you are wondering if the value of Cryptopunks will increase over the next 25 years you only need to ask: Will people still talk about them in 25 years?”

Collectors: Why collect? What do you believe?

Modern, digital technology is a tool, created and wielded by humans, ostensibly under our control. Throughout history, the adoption of new technologies has driven profound shifts in society and this has been especially true when the technologies connect humans in new ways (shipping, telephony, trains, airplanes, internet, mobile connectivity) that lead younger generations to live differently than those who matured ahead of them.

Today, most of us are living in two worlds at once: physical and digital. We breathe in the physical world where we hug our children, eat, sleep, make love, run, ride skateboards, and play vinyl records. Often simultaneously, we email, DM, scroll, heart, create, share, shitpost and type with thumbs in a world of small-yet-powerful computers connected to one another via TCP/IP. We value the opinion of our network neighbors far more than our physical ones. We operate in dual worlds most of our waking moments, and share data with the cloud while we sleep.

In my lifetime, as the five-year-old recipient of my brother's KISS vinyl, a teenage collector of VHS tapes about skateboarding and music, and MP3-trader-turned GM of Apple Music, I've lived through the digitization of all information. Obscure performances once mail-ordered from the classified ads in a newsprint magazine are now available to 5.52 billion Internet users with a simple keyword search on YouTube.

Now, we have begun the digitization of all value. The "renting services on the Internet" business (internet-services business) has a current marketcap of about $4.75 trillion. The "owning digital value" business (cryptocurrency) is currently valued at $3.2 trillion. I believe the "owning digital value" marketcap will be at least an order of magnitude larger than this "renting digital services" industry within the next 25 years, and if Instagram hadn’t chickened out of their digital collectible market the lines would already be beginning to blur. The value of Internet services is centralized with the shareholders of companies whose product is the user. The marketcap of cryptocurrency will at least partially belong to the world's digital citizens held in permissionless digital self-custody.

The digitization of value, however, has a cold start problem. Asset value is relative to network effect -- it only exists if we all agree it does. Adoption curves to new technologies always takes time but the emerging Internet of Value has a different foe than the 1990s Internet of Information. In 1999, digital media was challenging an $895 billion traditional media market;today, the crypto industry is challenging a $9 trillion banking industry. Replacing 3% credit card surcharges is inevitable but will take a long time and digital ownership is much more than just finance. It's trustless proof of humanity, identity, and anything else.

www.beastieboys.com in December of 1998.

Music apps hold "early adoptor" status in online history. Many of the first CD-ROMs, Shareware, Web and mobile applications were applications to find and listen to music. "Self-publishing" music platform IUMA pre-dates the World Wide Web. CD Baby bridged digital and physical self-publishing ten years before Amazon started allowing authors to publish their own books. The iPhone wouldn't have come into existence without the success of the iPod. There are many reasons music was the tip of the proverbial spear, among them relatively small file sizes, artist/album/track/genre being a remedial database challenge, and every college-age computer programmer loving and listening to music while they code.

Similarly, Digital Art is the tip of the digital value spear. Someone creates something. Someone else likes it. They exchange value. It's the simplest form of a digital economy. Scale helps, but isn’t required. As with traditional art and luxury goods, the number of market participants can be small relative to value. It only took two bidders to drive the value of Francis Bacon's Three Studies of Lucien Freud to $142.2 million dollars.

In the 1990s I was the conduit between the band Beastie Boys and their online fans. I posted tour dates, press articles, and photos from the stage. I kept the FAQ up to date and moderated the message board and IRC channel. We shared information about the band's not-for-profit and indie record label. As a "market" the fanbase was relatively small, but extremely passionate and dedicated. It felt as if the internet was made especially for communities like this to gather. I used to say my job was "to turn a casual listener into an obsessed fan".

Similarly today, the "obsessed fans of Kim Asendorf market" (who gather in a private Discord of which I am part) is very small. Yet if you enter you will find it is indeed a market with rising prices due to demand growing faster than supply.

When talking about value people often get stuck trying to puzzle out intrinsic value instead of simply admitting the obvious fact: Storytelling + Time = Value. Basquiat's work increases in value because the number of people who know the story increases while the supply does not. Luxury brands are trading on heritage and storytelling, not only products. Similarly, if you are wondering if the value of Cryptopunks will increase over the next 25 years you only need to ask: Will people still talk about them in 25 years? If yes then you have Storytelling + Time, which amounts to more value. If everyone forgets about Cryptopunks and stops talking about them, the value will decline. Intrinsic value be damned.

I'm not arguing that everything digital has value any more than I'm arguing that every song on Spotify is worth hearing. But I believe digital art holds and will continue to hold "early adopter" status as online economies grow because the barriers to creating very small test markets are very low.

Crypto Punks from higallery’s collection, paired with Egon Schiele sketches, c.1912.

A value exchange between a creator and a collector is a beautiful thing, especially relative to the business models of stealing and selling attention or speculating and gambling.

What’s the biggest difference from the traditional art scene?

I'm the least qualified to answer this question. In the traditional art world I rate as "museum-goer and collector of work from skateboarders I know".

Which is exactly why I've enjoyed the digital art world so much.

I love peering into the mind of a creator through their output.

I love being a patron.

I love the opportunity to get to know or even assist an artist in some way.

I studied and practice computer science; I'm more qualified to appreciate a generative art piece than a painting.

The digital art world is small and self-selecting, full of creative, intelligent, and often downright weird people. Those still participating in 2024 believe in something most do not with enough conviction to weather being negatively judged by their peers. I remember being called a "gayboarder", laughed at for wearing bermuda shorts and growing long bangs. But I can’t imagine my life without skateboarding and the people I met through it. I'm very comfortable in a crowd of idealistic, thoughtful, creativity-loving outcasts.

In 2022 my wife Hedvig and I were sitting around our dining table with FVCKRENDER and his wife, OSF, Farokh, and Raoul Pal. Raoul said, when talking about this moment in digital art and the digitization of value, "We will always remember that this was the time when everyone knew each other." I love that time. I'm proud to have been a skateboarder long before it was allowed in the Olympics and a punk rock fan long before The Offspring. I learned much more building pieces of the Internet than I do today as one its 5.52 billion consumers. I guess my preferred moment in any market is the one decades before "traditional".

Thanks for asking me to reply. I’m sure this isn’t the response you were expecting. I guess it’s dangerous to ask an idealist “what do you believe?” I hope it’s useful anyway!

Ian Rogers

Film

<div style="padding:73.47% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/1029421169?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0&badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Hitchcock on his collaboration with Dali"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Terry Reid - Silver White Light (Live at the Wight 1970) (Out of Print)

Matt Sweeney November 18, 2024

This raw “off the board” tape of British Rock’s finest singer features astonishing interplay between Reid and his band, and Terry’s ripping and flowing singing and guitar work is just staggering. The recording shows why Terry Reid was Aretha Franklin’s favorite rock singer. I wonder if this is the kind of band interplay Deadheads think they are hearing at Dead shows. Only one track from this can be heard online and that is a shame.

Matt Sweeney November 18, 2024

This raw “off the board” tape of British Rock’s finest singer features astonishing interplay between Reid and his band, and Terry’s ripping and flowing singing and guitar work is just staggering. The recording shows why Terry Reid was Aretha Franklin’s favorite rock singer. I wonder if this is the kind of band interplay Deadheads think they are hearing at Dead shows. Only one track from this can be heard online and that is a shame.

Matt Sweeney is a record producer and the host of the popular music series “Guitar Moves”. He is a member of The Hard Quartet (debut album out Fall of 2024). Rick reached out to Matt Sweeney in 2005 after hearing his “Superwolf” album, and invited him to play on albums by Johnny Cash, Neil Diamond, Adele and many others. Follow Matt Sweeney via Instagram.

Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain

Sheila Ostrander and Lynn Schroeder

Illuminations from a hidden world.