Five of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 17, 2024

The Five of Swords is a card of undoing, of our dreams that come crashing down. Here the Swords which have been gently building start to fall apart like a house of cards. This is the representation of a failed hypothesis...

Name: Defeat, the Five of Swords

Number: 5

Astrology: Air, Venus in Aquarius

Qabalah: Gevurah of Vau

Chris Gabriel August 17, 2024

The Five of Swords is a card of undoing, of our dreams that come crashing down. Here the Swords which have been gently building start to fall apart like a house of cards. This is the representation of a failed hypothesis.

In Rider, we find a smiling rogue picking up swords that have been lost in battle. Behind him two men mourn before a sea. The sky is cloudy. Two swords lay on the ground, and three are in hand. He is picking up the pieces, unmoved by what has occurred.

In Thoth, we find a reversed pentagram, a falling star made of chipped swords. Geometric figures sputter about it with falling petals. The card has the violet of Aquarius and the Green of Venus. Venus in Aquarius has dreams and desires, but lacks the grounding to actualize them, creating a distance and alienation.

In Marseille, we have a single central sword whose tip is weaving through the four arched around it. Through Qabalah, we find it signifies “The Anger of the Prince”.

The Anger of the Prince is Defeat. It is an anger toward reality, after his expectations, measurements, methods and plans were undone..

This is not defeat at the hands of another, but self undoing.

My great grandfather was a Mason, and a piece of advice he gave me was to “measure twice, cut once”.This card occurs as a result of incorrect measurements. We can imagine a car stranded out of gas on the side of the road, a disappointed couple and an amused tow truck driver taking a modern form of the Rider card..

The suit of Swords pertains to the mental sphere, which is the origin of our many defeats, foibles, expectations, and visions which fall apart when they meet the real world.

Aesop’s Astronomer, who despite his calculations of the stars falls into a well.

While the Five of Wands gives us the image of a tyrannical ruler who weighs too heavily upon his people, the Five of Swords is the image of a totally removed ruler, like Marie Antoinette, who when told that the peasants had no bread, replied: "Then let them eat cake."

While we often attribute the ‘airheadedness' of these dynamics to an ‘overdeveloped imagination’, it is in fact a failure of imagination.

It makes me think of how so many want to make art, only they need millions of dollars, expensive equipment, and the like, while the truly great artists find a way to bring their vision into reality with what they have in hand. They set aside unreal expectations for the sake of the art itself. Which requires more imagination?

The great thing about this card is that it functions as a prerequisite for the Six of Swords, which represents Science. These are the failed hypotheses, the experiments gone awry, the countless mistakes that are needed to develop a functional methodology.

When we pull this card, we are being shown a part of ourselves that holds these unreal ideas, illusions that we maintain which will be brought tumbling down by the world.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, we can be like the smiling fellow, pick up the pieces and try again. This is how we develop a true understanding of the world.

A Forager’s Take on Fairytales Pt. 1

Izzy Johns August 15, 2024

Long ago in Drumline, County Clare, in the late 19th Century, an old farmer and his wife huddled for warmth in a mud hut. Many a cold winter passed, and finally, the man agreed to build his wife a house of bricks and mortar. He set to work the following Spring. Not a day had passed when the old man received a visit from a traveler, who spoke these words…

Izzy Johns August 15 2024

Long ago in Drumline, County Clare, in the late 19th Century, an old farmer and his wife huddled for warmth in a mud hut. Many a cold winter passed, and finally, the man agreed to build his wife a house of bricks and mortar.

He set to work the following Spring. Not a day had passed when the old man received a visit from a traveler, who spoke these words:

“I wouldn’t build there if I was you. That’s the wrong place. If you build there you won’t be short of company, whatever else.”

The old man paid him no mind, but sure enough, the moment he and his wife lay down to rest in their new home, they were plagued by noise and disruption. Furniture was knocked over, cutlery strewn across the floor, crockery smashed. They couldn’t get a wink of sleep. But, as sure as day, whenever they went to investigate, they found nothing and no one. The old couple sought the help of the local preacher, who recognised this as the work of the Sidhe, the Little Folk of this land. He tried to exorcize the house, but to no avail.

After five sleepless nights, the man wearily set off to the market to sell their cows. It was the Gale day, the day that their rent was due, and money was sparse. English colonisers had seized land from the Irish farmers some years before. Now they were renting it back to them, and the rent was high.

The old man got a fair price for the cows, and he stopped at a roadside pub on the way home. It was there that he encountered the traveler once again. In desperation, the man begged the traveler for advice. He would do anything so that the Little Folk would let him rest. The traveler walked him home, and took him to stand in the yard, on the far side of the house.

He said:

“Now, look out there and tell me what you see.”

[…] “The yard?”

“No,” he says, “look again.”

“The road?”

“No. Look carefully.”

“Oh, that old Whitethorn bush? Sure, that’s there forever. That could be there since the start o’ the world.”

“D’you tell me that now?”

The old man walked out to the gable o’ the house, called [him], then says, “come over here.”

He did.

“Look out there, and tell me what do you see?”

He looked out from that gable end, and there, no farther away than the end o’ the garden, was another Whitethorn bush, standing alone.

“Now,” says the old man, “I told you. I warned you. The fairies’ path is between them bushes and beyond. And you’re after building your house on it.”

Upon the instruction of the traveler, the man built two doors in either side of the house, in line with the Whitethorns. From then on, the Little Folk had a clear passage, and the man and his wife were not bothered again.¹

“The higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view”

British Goblins, 1880. Wirt Sikes.

I was very struck by this account. It feels different to the rich, meandering folk-tale jewels I love so much, that are wrapped in mythos and allegory. Instead, this tale falls into the realm of family and community stories, that are still “lived in”, in this case, by the old couple’s grandson, who told this story to Eddie Lenihan in the living room of the very same house. He said that he still leaves the two doors ajar each night so as to let the fairies pass. There’s no use in locking them, he says, for they’ll only be open again by the morning.

Make no mistake, this story is not hearsay. A book of fairy tales might read like a book of fiction, but it isn’t. What we see in this tale, and so many others like it, is a relic of a complex faith system from times gone by, and it’s important that we storytellers hold it in that way. This story comes from Ireland, where the fairies are called Sídhe, or Sí, though often called by euphemisms to avoid catching their attention. The Sidhe are the descendants of the people of Danu, the Tuatha Dé Danann, a race of fallen Gods and Goddesses that dwell in the liminality between our world and the otherworld, the An Saol Eile. It’s only fair to acknowledge their providence, not least is it a crucial act of cultural preservation.

Fairies have a range of habitats depending on where you are live. In Ireland, they are particularly fond of two places: a lone Whitethorn (Hawthorn) tree, and the forts - those grand, grassy mounds of earth, often covered in a greater diversity of wild plants than their surroundings. In this tale, the old couple has disturbed not a habitat, but a passage between habitats. More savvy builders would have driven four hazel rods into the ground, marking out the proposed foundations of the house. If by the next day any rod had moved, the house should be built elsewhere.

The fairies in this story star in a role that I’ve seen in countless tales; defending their habitat from ecological destruction. Here, they were able to communicate with the intruders and resolve the problem quickly. It’s a good thing that the old couple were forthcoming. Fairies will always give warnings, but it’s perfectly within their power to cause grave suffering if those warnings aren’t heeded. They can be at best didactic and at worst violent, but they have no interest in troubling a person who isn’t troubling them. I can’t condone the violence, but I marvel at how proficient they are at protecting and stewarding the land. Plus, they greatly enrich the ecosystem. Various tales see fairies fertilizing soil for generous farmers, and producing abundances of wildflowers and fungi. It’s said that the rings of mushrooms we see in woodlands and meadows are where they’ve danced.

The Intruder, c.1860. John Anster Fitzgerald.

Thinking about this with an Ecologist’s gaze, fairies are a fascinating species. They might well be a larger genus with loads of regionally-specific variants like small people, spriggans, buccas, elves, bockles and knockers, browneys, goblins, dryads, gnomes and piskies. There’s a wealth of anecdotal evidence of their existence, thousands and thousands of stories, stretching back millenia, yet we’ve never successfully captured and studied them. Perhaps what makes this species most unique is their ability to outwit ours. Their cunning gently prods at our human arrogance, contesting our claim to be the most “developed” of species.

Far less frequently in the UK do we hear tales of the Little Folk interfering with larger property developments. In London, for example, you’ll scarcely come across a piece of land that hasn’t been leveled ten times over, and most Whitethorns are confined to cultivated hedges. I wonder how many forts have been destroyed in my neighborhood. Our lack of understanding of the fairies’ life cycles and physiology makes it pointless to speculate on why larger builds don’t experience ramifications from the little folk. It’s hard not to wonder if heavy machinery, giant crews of contractors and big blocks of hundreds of dwellings haven’t been too much for the fairies to contend with. I hate to think that, unbeknownst to us, urbanization might have wiped them out. If fairies are still around, it’s clear that they’re gravely endangered.

If this is the case, then it makes fairies one of over two million species under threat of extinction. It’d be such a shame if these creatures, these stories, and the feelings that they represent, disappeared altogether. I love this tale for giving us such a tangible example of humans making space for fairies and subsequently managing to co-exist peacefully. The fairies in this story are model land guardians, and from that we humans have a lot to learn.

Izzy Johns is a forager and storyteller. She teaches foraging under the monicker Rights For Weeds and manages the Phytology medicine garden in East London. You can find her work on Substack [rightsforweeds.substack.com] and Instagram [instagram.com/ rightsforweeds] .

¹As recounted to Eddie Lenihan in 2001 by the couple’s grandson, recorded in ‘Meeting the Other Folk…”

Against Fluency

Arcadia Molinas August 13, 2024

Reading is a vice. It is a pleasurable, emotional and intellectual vice. But what distinguishes it from most vices, and relieves it from any association to immoral behaviour, is that it is somatic too, and has the potential to move you…

Guilliaume Apollinaire, 1918. Calligram.

Arcadia Molinas August 13, 2024

Reading is a vice. It is a pleasurable, emotional and intellectual vice. But what distinguishes it from most vices, and relieves it from any association to immoral behaviour, is that it is somatic too, and has the potential to move you. A book can instantly transport you to cities, countries and worlds you’ve never set foot on. A book can take you to new climates, suggest the taste of new foods, introduce you to cultures and confront you with entirely different ways of being. It is a way to move and to travel without ever leaving the comfort of your chair.

Books in translation offer these readerly delights perhaps more readily than their native counterparts. Despite this, the work of translation is vastly overlooked and broadly underappreciated. In book reviews, the critique of the translation itself rarely takes up more than a throwaway line which comments on either the ‘sharpness’ or ‘clumsiness’ of the work. It is uncommon, too, to see the translator’s name on the cover of a book. A good translation, it seems, is meant to feel invisible. But is travelling meant to feel invisible – identical, seamless, homogenous? Or is travelling meant to provoke, cause discomfort, scream its presence in your face? The latter seems to me to be the more somatic, erotic, up in your body experience and thus, more conducive to the moral component of the vice of reading.

French translator Norman Shapiro describes the work of translation as “the attempt to produce a text so transparent that it does not seem to be translated. A good translation is like a pane of glass. You only notice that it’s there when there are little imperfections— scratches, bubbles. Ideally, there shouldn’t be any. It should never call attention to itself.” This view is shared by many: a good translation should show no evidence of the translator, and by consequence, no evidence that there was once another language involved in the first place at all. Fluency, naturalness, is what matters – any presence of the other must be smoothed out. For philosopher Friedreich Schlerimacher however, the matter is something else entirely. For him, “there are only two [methods of translation]. Either the translator leaves the author in peace, as much as possible, and moves the reader towards him; or he leaves the reader in peace, as much as possible, and moves the author towards him.” He goes on to argue for the virtues of the former, for a translation that is visible, that moves the reader’s body and is seen and felt. It’s a matter of ethics for the philosopher – why and how do we translate? These are not minor questions when considering the stakes of erasing the presence of the other. The repercussions of such actions could reflect and accentuate larger cultural attitudes to difference and diversity as a whole.

“The higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view”

Guilliaume Apollinaire, 1918. Calligram.

Lawrence Venuti coins Schlerimacher’s two movements, from reader to author and author to reader, as ‘foreignization’ and ‘domestication’ in his book The Translator’s Invisibility. Foreignization is “leaving the author in peace and moving the reader towards him”, which means reflecting the cultural idiosyncrasies of the original language onto the translated/target one. It means making the translation visible. Domestication is the opposite, it irons out any awkwardness and imperfections caused by linguistic and cultural difference, “leaving the reader in peace and moving the author towards him”. It means making the translation invisible, and is the way translation is so often thought about today. Venuti says the aim of this type of translation is to “bring back a cultural other as the same, the recognizable, even the familiar; and this aim always risks a wholesale domestication of the foreign text, often in highly self- conscious projects, where translation serves an appropriation of foreign cultures for domestic agendas, cultural, economic, political.”

The direction of movement in these two strategies makes all the difference. Foreignization makes you move and travel towards the author, while domestication leaves you alone and doesn’t disturb you. There is, Venuti says, a cost of being undisturbed. He writes of the “partly inevitable” violence of translation when thinking about the process of ironing out differences. When foreign cultures are understood through the lens of a language inscribed with its own codes, and which consequently carry their own embedded ways of regarding other cultures, there is a risk of homogenisation of diversity. “Foreignizing translation in English”, Venuti argues, “can be a form of resistance against ethnocentrism and racism, cultural narcissism and imperialism, in the interests of democratic geopolitical relations.” The potential for this type of reading and of translating is by no means insignificant.

To embrace discomfort then, an uncomfortable practice of reading, is a moral endeavour. To read foreignizing works of translation is to expand one’s subjectivity and suspend one’s unified, blinkered understanding of culture and linguistics. Reading itself is a somatic practice, but to read a work in translation that purposefully alienates, is to travel even further, it’s to go abroad and stroll through foreign lands, feel the climate, chew the food. It’s well acknowledged that the higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view. And to get the bigger picture is as possible to do as sitting on your favourite chair, opening a book and welcoming alienation.

Arcadia Molinas is a writer, editor, and translator from Madrid. She currently works as the online editor of Worms Magazine and has published a Spanish translation of Virginia Woolf’s diaries with Funambulista.

The Ace of Disks (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 10, 2024

The Ace of Disks is the seed of the earthy suit, from it all the disks grow. This is the foundation or cornerstone of an establishment.It is, in some ways, the most important card in the suit, as nothing that lasts can be built on a weak foundation…

Name: Ace of Disks

Number: 1

Astrology: Earth

Qabalah: Kether of He ה

Chris Gabriel August 10, 2024

The Ace of Disks is the seed of the earthy suit, from it all the disks grow. This is the foundation or cornerstone of an establishment.It is, in some ways, the most important card in the suit, as nothing that lasts can be built on a weak foundation.

The image is simple, that of a coin, and flowery growth.

In Rider, we have a divine hand bringing forth a pentacle, a coin bearing the five pointed star. Beneath is a garden and flowery terrace. There is a path leading to distant mountains.

In Thoth, we have a coin bearing a pentagram and a septagram within it. At the center is the personal seal of Crowley, three interlocked circles marked “666” and the Greek around the border reads “To Mega Therion” or “The Great Beast”, this is the autograph of the deck’s creator. Beyond the central coin we have helicopter seeds and verdant imagery.

In Marseille, a flowery coin is depicted with four flowers. Qabalistically, this card is the “Crown of the Princess”: the Princess of the Earth is crowned by a Seed, and crowned by her foundation.

The divine hand of Rider is absent from Marseille, where the hands of God appear only in the Ace of Wands and the Ace of Swords, as those two elements are considered “higher”. The Earth is the lowest element, the most mundane and it is only from this base place that we can reach the highest forces.

It calls to mind Matthew 7:25: And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock.

The Ace of Disks must be the rock of our further exploration. From this foundational anchor we can remain sturdy in the midst of spiritual chaos.

When we say that a loved one is “our rock”, this is the card.

Yet in Thoth, we find the helicopter seed, a moving seed, a seed that flies! Showing us that this foundation need not be literally set in the ground, a true firmness and foundation can move with us, for it comes from within.

When we pull this card, we are being shown a foundation, which can be material, whether it be a place where we can establish our work or where we are able to spiritually flourish. As for money, think of “seed capital”.

This card represents both the necessary energy and the space to build.

Balancing on the Earth

Tuukka Toivonen August 8, 2024

Volumes have been written about how we humans might enter a more balanced relationship with the Earth. Such contributions tend to adopt a disembodied, impersonal perspective, building on a conceptual language removed from our daily experience. What would we discover if we instead approached the question of balance more literally? What new possibilities and inventions might be revealed if we looked anew at how we seek to balance on the Earth, in an embodied sense? And can such a way of thinking lead to a more resonant connection with the ground one stands, walks and dances upon?

Artificiosa Totius Logices Description (1614). Meurisse and Gaultier.

Tuukka Toivonen August 8, 2024

“Be aware of the contact between your feet and the Earth. Walk as if you are kissing the Earth with your feet.” - Thich Nhat Hanh

Volumes have been written about how we humans might enter a more balanced relationship with the Earth. Such contributions tend to adopt a disembodied, impersonal perspective, building on a conceptual language removed from our daily experience. What would we discover if we instead approached the question of balance more literally? What new possibilities and inventions might be revealed if we looked anew at how we seek to balance on the Earth, in an embodied sense? And can such a way of thinking lead to a more resonant connection with the ground one stands, walks and dances upon?

From the moment our lives commence, we begin to manoeuvre our bodies in relation to other beings, to gravity and to the broader physical world that surrounds us, eventually gaining the ability to stand up and walk. As the contemporary German theorist of resonance and societal acceleration Hartmut Rosa suggests, this is precisely where we must start if we are to understand shared human ways of being and relating to the world:

“The most basic and obvious answer to the question ‘How are we situated in the world?’ is simply: on our feet. We stand upon the world. We feel it beneath us. It sustains our weight. The certainty that the ground we stand on will bear us up is among the most fundamental prerequisites of our ontological security. We must be able to depend on it, and we depend on it blindly in the normal course of everyday life. If the ground were to unexpectedly collapse, if the earth opened up beneath us, we would experience this as a shocking event, a traumatic loss of that very security.”¹

Illustration to Emerson’s Nature (c.1838). Christopher Pearse Cranch.

Given that our ability to stand and walk upon supportive ground defines a major part of our existence, it follows that the act of balancing – however unconsciously practised – must also be central to how we exist and situate ourselves within, and in relation to, the world. Without sufficient balancing, there can surely be no consistent experience of ontological security.

Yet, it seems we have unwittingly lost, or at least narrowed, our ability to balance on the Earth as we have adjusted to contemporary styles of living. Could it be that in this process we might have degraded not only our sense of security and confidence – adding to the many anxieties our societies appear currently steeped in – but also our ability to enter into a genuine relationship with the world through our bodies?

We prefer to walk on smooth pavements rather than textured, uneven forest paths. We like to traverse our cities in high-tech vehicles that remove us from any direct contact with the ground. Some of us regularly ride a bicycle but we rarely develop our balancing skills beyond our initial learning spurts. Entire cultures and infrastructures seem to be designed to shield us from encountering balancing challenges or disturbances. Even the yoga classes we attend – planting our bare feet on tidy studio floors and mats – rarely push us to explore our bodies’ ability to find balance in alternative, subtle ways. As Rosa notes in his remarkable book on resonance, despite their seeming innocuousness, even the shoes enfolding our feet “establish a highly effective ‘buffering’ distance between body and world that allows us to move from a participative to an objectifying, reifying relationship to the world”.

If the result of all this shielding is that we have weakened our ability to engage in balancing at the embodied level, how might we reclaim and strengthen that ability? We must reach for a sense of balance that is flexible and dynamic more than rigid and static, productive of a lively sense of security as well as relationality. The good news is that life offers abundant opportunities to experiment with diverse ways of balancing on the Earth if we choose to grasp them.

“The Universe is a limitless circle with a limitless radius. This condensed becomes the one point in the lower abdomen which is the center of the Universe”

Skateboarding, an early hobby growing up in Southern Finland, taught me some early lessons about the art of balance. First, learning to ride the streets on a wobbly board and mastering a range of jumps and pivots turned balancing into a playful, addictive challenge. Inevitably, I also quickly learned a second lesson: failing to balance could lead to tremendous pain. The feedback from losing one’s footing was immediate and merciless – there were no verbal excuses or buffers that could render impact with the pavement any less punishing. Yet for all these important learnings, I subsequently realized that not only did skateboarding ultimately keep me at a certain distance from the ground (through shoes, boards and asphaltic surfaces) but it also imposed limits on how I could connect with my own body.

By contrast, contemporary improvisational dance offers a form of playful movement that promotes a more nuanced and experimental connection with one’s body. It invites us to explore unfamiliar ways of moving ourselves upon the ground and through the air while responding fluidly to others around us. The neuroscientist and brain health champion Hanna Poikonen of ETH Zurich suggests that it is the way in which those engaged in improvisational dance listen to their internal signals that sets this form of dance apart. By becoming so attuned to their bodies, improv dancers allow embodied sensations to guide their next actions in the moment. This bodily intelligence invites one to explore diverse ways of balancing in an emergent fashion. Practitioners may choose to intentionally confront and experiment with various sources of stiffness, shakiness and difficulty in relation to balance. What emerges (along with improvements to one’s health) is a certain sense of comfort with feeling unbalanced, and from this the profound realization that as living and moving human beings, we are constantly engaged in balancing rather than “in balance”. Perfect balance is neither possible nor desirable, for it would fix us in place, like lifeless statues. Instead, the options available to us are not binary (being in balance vs losing one’s balance) but dynamic and infinite in character: it is always possible for us to discover new, lively ways of balancing.

Anatomical Flap Book (1667). Remmelin.

Japanese martial arts such as karate and aikido offer a more spiritually tuned approach to balance and movement. Sharing with improvisational dance a strict preference for encountering the ground, floor or tatami barefoot, traditional martial arts place central importance, both philosophically and practically, on a specific area roughly two inches below the bellybutton. Known as tanden or sometimes as hara, this special area inside the lower abdomen is considered key to accessing one’s highest powers through the unification of body, mind and spirit.

While Japanese martial arts and movement instructors often point out that tanden is located at or near the body’s centre of gravity in a physical sense, it is tanden’s role as a focal point or container for universal energy that is given far more primacy. In the words of the aikido master and Ki Society founder Tohei Koichi (1920-2011), “[t]he Universe is a limitless circle with a limitless radius. This condensed becomes the one point in the lower abdomen which is the center of the Universe”.²

In practice, it is through mindful breathing that outside energy is thought to enter the body, allowing the practitioner to feel that they exist as part of nature and its ongoing cycles, as observed by Nagatomo Shigenori in Attunement Through the Body (1992).

Remarkably, then, power and balance in martial arts are achieved not only through the efforts of the individual practitioner but through an embodied and flowing sense of connection with the natural world that envelopes them. Here, breath serves as the ongoing link between outer and inner energies, between the individual and the world..Balance is found when both come together through vital ki energy and when that energy is harmonized with movement.

So, it seems that balancing on the Earth is not quite as ordinary or narrow a process as we might have initially suspected. Once you begin to reconnect with your body and its ability to balance in subtly, or dramatically, different ways, potent insights start to emerge. We are never “in balance” but rather always balancing. That act of balancing – which we normally carry out unconsciously – can be made more intentional and vibrant. It can even offer paths to “embodied integration” with the living world and the universe, through the alignment of breath and movement. Through dance and other playful forms, it is entirely possible to become more comfortable with fluidity and lack of stability. Falling out of balance is not always a bad thing, even if it leads to temporary pain. Rather, it is the refusal to fully engage with our bodies, their incredible capacities for motion and the rich textures of the Earth that may leave us with a chronic sense of unsteadiness.

One secret to making our existence genuinely lively and resonant may be to redefine balancing as a conversation we can have with the Earth with our bodies. As with any dialogue that transcends conventional boundaries, binary distinctions and assumptions, it might prove as nurturing and transformative as the conversations you have with the people you most gravitate towards.

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.

¹ Rosa, Hartmut (2019). Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World. Polity Press, p. 38.

² Tohei, Koichi (2022). Ki Sayings. Ki Society HQ, p.5

Lapis Lazuli (Artefact IV)

Ben Timberlake August 6, 2024

The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural…

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 4

Description: Ultramarine from Lapis Lazuli

Location: Sare-e-Sang, Badakhshan, Afghanistan

Age: 6000BC to Present

Ben Timberlake August 6, 2024

Blue is the color of civilization. It is the color of heaven.

When the first prehistoric artists adorned the cave walls, they used the earth colors: reds, browns, yellows, blacks. There were no blues, for the earth very rarely produces the color. Early peoples had no word for blue: it doesn’t appear in ancient Chinese stories, Icelandic Sagas, the Koran, or Sumerian myths. In the Odyssey, an epic with no shortage of opportunities to use the word, there are plenty of blacks and whites, a dozen reds, and several greens. As for the sea - Homer describes it as “wine-dark”.

Philologist Lazarus Geiger analyzed a vast number of ancient texts and found that the words for colors show up in different languages in the same sequence: black and white, next red, then either yellow or green. Blue is always last, arriving with the first cities and the smelting of iron. Homer’s palette, at the end of the Bronze Age, sits neatly within this developmental scheme.

The Egyptians had a word for blue, for they also had the tools of civilization, long-distance trade, and technology, that allowed them to seek out and harness the color. 6000 years ago, the very first blue they used - the true blue - was ultramarine from Lapis Lazuli (the ‘Stone of Heaven’), found in the Sar-e-Sang mines in northern Afghanistan. It was this blue that adorned the mask of Tutankhamun, and that Cleopatra wore, powdered, as eye-shadow.

Lapis lazuli was so expensive that the Egyptians were driven to some of the earliest chemistry experiments - heating copper salts, sand and limestone - to create an ersatz turquoise that was the world’s first synthetic pigment. The technology and recipe spread throughout the ancient world. The Romans had many words for different varieties of blue and combined Egyptian Blue with indigo to use on their frescoes. But none of these chemical creations or combinations could match the Afghan lapis for the brilliance of its blues.

“The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural.” - Wassily Kandinsky

The Virgin in Prayer, Giovanni Battista Salvi da Saassoferrato, c.1645.

At the Council of Ephesus in 431AD, ultramarine received official blessing when it was decided that it was the color of Mary, to venerate her as the Queen of Heaven. Since then it has adorned her robes and that of the angels. Ultramarine was the rarest and most exotic color. Its name - meaning ‘beyond the sea’ - first appeared in the 14th century, given by Italian traders who brought it from across the Mediterranean. Lapis Blue was more expensive than gold and was reserved for only the finest pieces done by the most gifted artists.

It was the most expensive single cost in the whole of the Sistine Chapel and it is said that Michelangelo left his painting The Entombment unfinished in protest that his patron wouldn’t pay for ultramarine. Raphael reserved the color for the final coat, preferring to build the base layers of his blues from Azurite. Vermeer was a master of light but less good at economics: he spent so much on the ultramarine that he left his wife and 11 children in debt when he died.

Once again, mankind turned towards chemistry to search for a cheaper blue: in the early 1800s France’s Societé d’Encouragement offered a reward of 6000 Francs to a scientist who could create a synthetic ultramarine. The result was ‘French Ultramarine’ a hyper-rich color that is still with us to this day.

But 200 years later there is still a debate as to whether we have lost something. Alexander Theroux in his essays The Primary Colors wrote “Old-fashioned blue, which had a dash of yellow in it... now seems often incongruous against newer, staring, overly luminous eye killing shades”.

Anthropometry: Princess Helena, Yves Klein, 1960.

True ultramarine is perfect because of its flaws. It contains traces of calcite, pyrite, flecks of mica, that reflect and refract the light in a myriad of ways. Many artists have continued to prize it for its shifting hues, the heterogeneity of the brushstrokes it creates, the feelings it stirs in us. As Matisse said, ‘A certain blue penetrates the soul’.

Yves Klein worshiped the color and used the synthetic version but he owed his inspiration to the real thing. Klein was born in Nice and grew up under the azure blue Provencal skies. At the age of nineteen he lay on the beach with his friends - the artist Arman, and Claude Pascal, the composer - and they divided up their world: Arman chose earth, Pascal words, while Klein asked for the sky which he then signed with his fingers.

It was only when Klein later visited the Scrovegni Chapel and saw the ultramarine skies of Giotto’s paintings did he understand how to achieve his calling. Klein devoted his brief life to the color, he even patented International Klein Blue (IKB), a synthesis of his childhood skies and the stone of heaven itself.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

The Three of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 3, 2024

The Three of Cups is the card of emotional intimacy, and the act of pouring one's heart out. These are the emotional declarations that arise from a night of drinking as the heart overflows…

Name: Love, the Three of Cups

Number: 3

Astrology: Mercury in Cancer

Qabalah: Binah of He

Chris Gabriel August 3, 2024

The Three of Cups is the card of emotional intimacy, and the act of pouring one's heart out. These are the emotional declarations that arise from a night of drinking as the heart overflows.

In Rider, we see three women making a toast, their cups are raised high. Each has a flowing dress and flowing hair, and they seem to be dancing in an orchard. The sky is blue, and they are smiling.

In Thoth, we see three cups, where each seems to be formed like a cluster of grapes. Lotuses shower water into them, and they flow into one another. The cups are crimson, the lotuses yellow, and the ocean they sit upon is a deep blue. This card is Mercury in Cancer, thus the gold and blue.

In Marseille, we find the same structure as Thoth, one cup atop two, and flowers going between. Through Qabalah we find the phrase “The Understanding of the Queen”

The Understanding of the Queen is Abundance.

The astrological character of this card, Mercury in Cancer, or emotional communication is perfectly symbolized in Rider Waite, it is the card of “Girls Night”, when women get together to drink wine and talk. This is the great catharsis of relieving pressures that build up throughout life when we pour our hearts out into one another's cups and drink.

As this card belongs to the Queen, the idea of speaking one's heart tends to be seen as feminine. Though exemplified and illustrated as being the domain of women, it does not exclude male friendships and the drunken expressions of love that accompany it.

These are the emotions brought out by drink, whether regularly or rarely. The gender divide is essential to this being the Queen’s Understanding, as opposed to the King’s Understanding in the Three of Wands, which is daily virtue.

We should acknowledge that these gender divides and stereotypes are outdated and can be quite silly, but for the purposes of understanding the Tarot it is necessary to explore them.The Three of Wands, the masculine equivalent to this feminine card, is about the masculine drive for simplicity, as opposed to the feminine drive for abundance seen here. The Stoic King might take pride in sleeping on the floor, but the Queen knows a royal bed is more fitting.

Of course, this is not an abundance of stuff, but of emotion. Our feelings are a great store of value; they are not a hindrance or a flaw, but a brilliant source of connection to our deepest truth. This card shows that the Queen understands how to utilize this wealth of emotion through engagement.

The division of elements and genders is not essentially biological, but spiritual, anyone can experience all aspects of the tarot.

When pulling the Three of Cups we are asked to engage in emotional catharsis, to see the abundance we have before us, to let our hearts overflow. It can also signify a coming abundance, an event that will bring much emotion with it. Do not shy away from your heart, let it be abundant!

Numerology, Fibonacci, and Magic

Flora Knight August 1, 2024

Fibonacci sequences may not hold a prominent place in traditional magic or witchcraft, but to study them reveals the underlying principles that are deeply intertwined not just with sacred geometry and the natural spirals of the universe, but with the mystical world in it’s totality…

Albrecht Durer, Melencolia I featuring a magic numerology square. (1514)

Flora Knight August 1, 2024

Fibonacci sequences may not hold a prominent place in traditional magic or witchcraft, but their underlying principles are deeply intertwined with sacred geometry and the natural spirals of the universe. Two spiritual interpretations derived from the Fibonacci sequence are particularly noteworthy in our modern magical understandings, and particularly in the practice of Wicca: the concepts of twin flames and the number 33 sequence.

The spiral and golden rectangle of the Fibonacci sequence.

The idea of twin flames has long been embedded in magical traditions. Love, often symbolized by two flames, is a recurring theme in love spells and incantations, where lighting two candles side by side is believed to elevate love to a higher spiritual plane. This concept is represented by the number 11, a significant number in witchcraft. The Fibonacci sequence begins with 1 + 1, a numerical foundation that has been embraced by some modern Wicca sects as resonating with the essence of twin flames.

Another intriguing use of the Fibonacci sequence involves starting the sequence with the number 33. The number 3 represents the mind, body, and spirit, so 33 symbolizes the spiritual realization of these elements. When the Fibonacci sequence begins with 33, it leads to important numbers such as 3, 6, and 9, which are said to represent the ascension of the universe. Mapping these numbers on a grid also forms a pentagram, a powerful symbol in Wicca.

The 12th number in this modified Fibonacci sequence is 432, a number of profound significance in modern Wicca. The frequency of 432 Hz resonates with the universe’s golden mean, Phi, and harmonizes various aspects of existence including light, time, space, matter, gravity, magnetism, biology, DNA, and consciousness. When our atoms and DNA resonate with this natural spiral pattern, our connection to nature is enhanced.

The number 432 also appears in the ratios of the sun, Earth, and moon, as well as in the precession of the equinoxes, the Great Pyramid of Egypt, Stonehenge, and the Sri Yantra, among other sacred sites. While Fibonacci sequences were not commonly used in traditional magic before the 20th century, we see their presence everywhere, and they are meaningful in explanations of sacred geometry.

“This sequence, when viewed through a spiritual lens, reveals the underlying order and symmetry in nature, guiding us toward a deeper appreciation of the divine patterns that govern our existence.”

But beyond just Fibonacci, the study of numbers reveals secrets of the world, and to understand the magical perspective of the world, we must understand how different numbers carry various symbolic meanings:

William F. Warren, Illustration from Paradise Found. (1885).

1: The universe; the source of all.

2: The Goddess and God; perfect duality; balance.

3: The Triple Goddess; lunar phases; the physical, mental, and spiritual aspects of humanity.

4: The elements; spirits of the stones; winds; seasons.

5: The senses; the pentagram; the elements plus Akasha; a Goddess number.

7: The planets known to the ancients; the lunar phase; power; protection and magic.

8: The number of Sabbats; a number of the God.

9: A number of the Goddess.

11: The twin flames; the number of ethereal love.

13: The number of Esbats; a fortunate number.

15: A number of good fortune.

21: The number of Sabbats and Esbats in the Pagan year; a number of the Goddess.

28: A number of the Moon; a number 101 representing fertility.

The planets are numbered as follows in Wiccan numerology:

3: Saturn

7: Venus

4: Jupiter

8: Mercury

5: Mars

9: Moon

6: Sun

Numerology has been a significant aspect of witchcraft for nearly 3,000 years, with most numbers being assigned specific meanings by various magical traditions. The most consistent sacred numbers, linked to sacred geometry, are 4, 7, and 3. These numbers represent the universe, the earthly body, and the seven steps of ascension, respectively.

The story of the Tower of Babel illustrates the ancient understanding of the universe through numbers. The tower's seven stages were each dedicated to a planet, with colors symbolizing their attributes. This concept was further refined by Pythagoras, who is said to have learned the mystical significance of numbers during his travels to Babylon.

The seven steps of the tower symbolize the stages of knowledge, from stones to fire, plants, animals, humans, the starry heavens, and finally, the angels. Ascending these steps represents the journey towards divine knowledge, culminating in the eighth degree, the threshold of God's heavenly dwelling.

The Tower of Babel.

The square, though divided into seven, was respected as a mystical symbol. This reconciled the ancient fourfold view of the world with the seven heavens of later times, illustrating the harmony between earthly and cosmic orders.

In contemporary Wicca and broader spiritual practices, the exploration of numerology and Fibonacci sequences opens new pathways to understanding the universe and our place within it. These numerical patterns and sequences are not just abstract concepts; they reflect the intricate designs of nature and the cosmos. By integrating Fibonacci sequences into spiritual practices, modern Wiccans and seekers of wisdom can tap into a profound sense of unity and harmony with the natural world.

The Fibonacci sequence, with its origins in simple arithmetic, evolves into a complex and beautiful representation of life's interconnectedness. This sequence, when viewed through a spiritual lens, reveals the underlying order and symmetry in nature, guiding us toward a deeper appreciation of the divine patterns that govern our existence.

As we continue to explore and embrace these ancient and modern numerological insights, we can uncover new layers of meaning and connection. The study of numbers in any form invites us to see the world not just as a series of random events, but as a harmonious and purposeful tapestry. This perspective encourages a more profound spiritual journey, where every number, pattern, and sequence becomes a gateway to greater wisdom and enlightenment.

Flora Knight is an occultist and historian.

Pay Attention: Simone Weil (1909-1943) and the Art of Selflessness

Nicko Mroczkowski July 30, 2024

How do you live a good life? This deceptively simple question is the source of the entire Western philosophical tradition. A certain path was laid by Socrates and we’ve walked it since, yet all of its detours eventually take us back to the original mystery…

“She was the patron saint of all outsiders.” – André Gide

Nicko Mroczkowski July 30, 2024

How do you live a good life? This deceptively simple question is the source of the entire Western philosophical tradition. A certain path was laid by Socrates and we’ve walked it since, yet all of its detours eventually take us back to the original mystery.

Philosophy, of course, is also about knowledge and truth, but these things are worth little without a purpose in sight. It’s hard to admit, but not all knowledge is valuable. Consider ‘Information’, an iconic prose poem by American writer David Ignatow, which makes this point perhaps more clearly than any piece of nonfiction could. Its unnamed narrator describes the pleasure they’ve taken in counting out each of the two-million-something leaves of a particular tree. Knowledge is gained, it’s close enough to the truth, but it offers nothing.

Generous in Pardoning the Offenders, Francesco I d’Este. 1659.

The proper task of the philosopher has always been using knowledge to teach us how things should be; while the question of how they are is best left to the scientists. Simone Weil, a real philosopher’s philosopher, understood this prompt, but took things further. For her, to be a philosopher is not just to contemplate and tell us about ‘the good’, but to strive to actually be good. As she writes in her notebooks, ‘philosophy (including problems of cognition, etc.) is exclusively an affair of action and practice’.

Her unusual and tragically brief life is testament to this conviction. Born into a fairly wealthy family of professionals in Paris, she began her philosophical education at the prestigious École normale supérieure, which produced such celebrity intellectuals as Jean-Paul Sartre, Jacques Derrida, and Henri Bergson. Yet from a young age, she was notorious for refusing the comforts of her privilege and campaigning for the less fortunate. When granted a year’s sabbatical from the comfortable secondary-school teaching post that she secured after her graduation, she opted to build cars as an unskilled female (and therefore especially exploited) labourer in factories across Paris.

These episodes and tendencies are as much a part of her philosophical legacy as her ideas. When it comes to Weil, we need to look not only at what she wrote, but also what she did. Though she never actually published a full-length book, probably she was both too modest and too busy, there is no shortage of writing from Weil. Each of her texts is really the product of her experiences and the different phases that scholars sort them into – Marxism, Platonism, Christian mysticism – are also descriptions of the different periods of her personal life.

This is all pretty weird for a philosopher in the Western tradition. Many of us have discussed the relationship between theory and practice – the distinction originates in the work of Plato, the very first of the greats – but few have practised their theories to the extent that Weil does. She herself speaks of the ‘pettiness’ of the philosophers in their personal lives. Not necessarily to their discredit, but the great philosophers of the West have largely been armchair contemplators, favouring intellectual philosophical labours over manual ones.

“The best thing the individual can do is make themselves as small as possible; but also as large as all of creation.”

Not so with Weil, clearly. She believed that if, like any deep thinker, you really pay attention to something, really, you’re also already involving yourself in it. For her, to truly pay attention is to bring about a modification of one’s very being: namely, its disappearance. To be absorbed in something enough that the self fades from view. We typically associate paying attention with an active mental strain, as if our brains were squinting, as they might be in a boring lecture. Weil argues that this has it the wrong way around. It’s not so much that we’re training our focus on something, but more that we’re keeping everything else back – our desires, hang-ups, interests, and momentary emotions – in order to make space for the thing we’re attending to. And the strain we feel is the impatience to get back to our own matters. This is why she refers to attention as a ‘negative effort’, or as essentially passive. The wordplay is clearer in French: attention is attente (waiting), and paying it means anticipating, in large and small ways, the delivery of something bigger than us. When we listen carefully to a close friend, for example, are we not really setting aside our own cares and hanging out for whatever it is they want to confide in us, on their terms, which have become ours?

The Eye of God, Georgiana Houghton. 1862.

This way of thinking about attention has some consequences that are, once again, pretty strange. If attention is an emptying-out of the self, then a morality based upon it is one of radical selflessness. In contrast, Western philosophy has almost always held the individual and their freedom as the basis for any code of conduct. There are three traditional ways of establishing this foundation: thinking about how one could make oneself an outstanding person (Aristotle); thinking about the responsibilities that come with being a free individual (Kant); and thinking about how one’s actions impact the world outside them (utilitarianism).

Weil’s ethics of attention sidesteps these problems altogether. The best thing the individual can do, for her, is make themselves as small as possible; but also as large as all of creation. To live for others is her ultimate maxim. It makes sense, I think, why Weil’s life went the way it did. She saw the temptations of comfort as things that would ground her in herself. They were obstacles to, rather than opportunities for, the diversity of experiences that belongs to goodness. And she sought out this latter diversity by practising solidarity with the oppressed in every available context.

She certainly took this moral project to the extremes. She died of a heart attack at age 34. According to her biographers, she felt that she had to subject herself to the same conditions that her comrades were suffering in occupied France, having herself left for London to protect her family, and so she effectively starved herself to death. It’s difficult to say exactly whether this is an example to follow, but her compassion for others borders on the saintly. And her lesson is equally difficult to ignore: the right kind of knowledge is knowledge of others, and the right kind of life uses this knowledge to make things better for everyone.

A good life begins with paying attention to the things outside us, without cynicism, bitterness, or fear. We can’t understand who we are in the world just by thinking about ourselves. It all seems so obvious when put like this: how could we know what being good is without meeting the world we’re being good to? Like Buddha himself, we need to go out there and see for ourselves. Ironically, this kind of openness to others only strengthens our sense of the uniqueness of each individual.

This, then, is Weil’s advice. Be good: listen, lose yourself in the world, and in doing so, belong to it.

Nicko Mroczkowski

The Ace of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel July 27, 2024

The Ace of Wands is the seed, the catalyst, and the Promethean spark that sets the suit of Wands aflame. It is the very idea of fire. Across the three decks, we have the image of a gnarled stick emanating energy…

Name: Ace of Wands

Number: 1

Astrology: Fire

Qabalah: Kether of Yod

Chris Gabriel July 27, 2024

The Ace of Wands is the seed, the catalyst, and the Promethean spark that sets the suit of Wands aflame. It is the very idea of fire. Across the three decks, we have the image of a gnarled stick emanating energy.

In Marseille, a hand comes through a ruffled portal, holding a large stick, one can see it came from a tree for twigs have been cut, and rays of energy surround it.

In Rider, a gleaming hand comes forth from a cloud, above a mountain and stream, it holds a stick still covered in leaves.

In Thoth, we have a far more vibrant image, deep reds and oranges make up this stick, with flaming Yods forming the Tree of Life. This is essentially an image of the formation of the Suit of Wands, a singular fire and its tenfold manifestations.

The Ace of Wands is a brilliant card and the first of the Minor Arcana. Fire is both the first element of the Tetragrammaton and the first divine energy. When we see this card, we should think both of a robed wizard with his magic wand, and of a matchstick, a miniature mundane wand. With a simple matchstick, one can set fire to the world.

Prometheus was a Titan in Greek mythology, his name means “Foresight”. As he foresaw the Olympian victory over the Titans, he changed sides. Though a friend to Zeus, Prometheus liked mankind. After Zeus took fire away from man as a punishment, Prometheus returned the gift of Fire by way of a stick, a hollow fennel stalk that hid the fire within it.

Man was given not simple material fire, but the very idea of conjuring it. Each stick holds the secret of fire, but only when the art of friction is applied. When we light a match, we utilize that divine gift - with wood and friction we once again create fire.

The Ace of Wands is more than a matchstick. To expand the idea more fully, we need only look down to the material body. The Wand can also be understood as the creative Phallus. Myth assures us that the divine mirrors the human, even our vulgarity: the Egyptians imagined their world had been formed by the masturbation of a lonely God, Atum.

God uses tools for the sake of creation, or at least, God is understood through symbols we are able to comprehend, and thus the body of man reflects the creative ability of the divine.

Whether the Wand in question is a phallus, an engraved ceremonial staff, or a matchstick, its goal is to manifest Fire. As the story of Prometheus shows, fire is the only element man could not conjure on his own. We are made of earth, and we shape the Earth, made of water, and our mouths bring forth spit, made of air, and we breathe it. Fire, the electric energy that gives us life, was entirely out of our control until we were given it. Fire is the vital energy.

When you pull the Ace of Wands, you are given the Promethean flame. With the tiniest spark of Will, you may manifest a brilliant fire.

Monuments to Gesture

Isabelle Bucklow July 25, 2024

Writing is one of those traces left behind when a hand, an instrument, and a thought meet upon, and move across, a surface. For that writing to be ‘comprehensible’ there must also converge a whole cultural system of rules and conventions which the writer and reader share – the ‘language’…

Letter (page 1), from the portfolio "Letter and Indices to 24 Songs", 1974. Hanne Darbovan.

Isabelle Bucklow July 25, 2024

“To write is to produce a mark that will constitute a sort of machine which is productive in turn, and which my future disappearance will not, in principle, hinder in its functioning”¹

Last month we looked at the gesture of grasping (a tool), and how the chaine operatoire (an anthropological tool) sought to grasp the sequence of gestures that bring something into being. Yet, gesture still slipped between our fingers, evading language and method.The gesture ‘is always a gesture of not being able to figure something out in language’, so said Agamben.² But this ‘not being able to figure out’ simultaneously contains the gesture of trying to figure out. And so if a gesture is always about figuring out, then attempts at definition and completion are futile, because gestures operate in the sphere of potentiality. If we are to inch closer to the nature of being-in-gesture, we must turn to its traces – those figurations of a once-present gesture.

Two Figures from Emersons Nature, c.1938. C.P. Cranch.

Writing is one of those traces left behind when a hand, an instrument, and a thought meet upon, and move across, a surface. For that writing to be ‘comprehensible’ there must also converge a whole cultural system of rules and conventions which the writer and reader share – the ‘language’ Agamben refers to. But even before that, before the lightness of the thought-just-thought hardens into meaning, think of Brian Eno and John Cale singing ‘up on a hill, as the day dissolves’, his ‘pencil turning moments into line.’³ These ‘lines’ could be a drawing or a song verse in cursive script, but just because those moments and thoughts have turned into line, that is not to say they have arrived at a stabilised signification: prior to being connected up to make identifiable characters and made ‘meaningful’ (by way of rules and conventions) , a line is quintessentially visual, an abstract, pure form.

Hanne Darboven (1941-2009) was a conceptual artist who, for most of her life, lived and worked in her family home in a suburb of Hamburg. Between 1966-68 she visited New York where she became good friends with Sol LeWitt and Lucy Lippard, pioneering conceptual artists and thinkers of the day. New York was where Hanne ‘tried to find something that [she] could work on for [her] whole life, it was where [she] built [her] work.’⁴ That work consisted of handwritten grids and columns of dates, equations, scripts, and transcripts; looping ‘u’s repeated then crossed out resembling lacework woven into graph paper; images and pages collected and collaged. Despite the incomprehensibility of her lines and cryptic mathematical prose, and the self-admitted fact that ‘the writing fills the space as a drawing would [and] turns out to be aesthetic’, Darboven insisted she was ‘a writer first and a visual artist second.’⁵ Her work was obsessive, ascetic, encyclopedic, machinic, and mesmeric. It is pure structure, pure gesture.

In a letter to Sol LeWitt, Hanne said of her work ‘I write but I describe nothing’. Seemingly a paradoxical endeavour, there is logic to this illogic. Writing is the act (and actualisation) of thinking, while language is the description of it. Writing need not entail expressive language, instead writing can simply reproduce writing. Clarice Lispector wrote, in her Discovering the World, ‘In order to write the only study required is the act of writing itself.’⁶ And Darboven did study the act: in the monastic tradition of the biblical scribe, she would copy passages from Goethe, Brecht, Diderot, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Gertrude Stein, Rilke, Sartre – retracing their studious concentration and hand movements line by line. As art-historian Briony Fer has observed, what Darboven embarked on was ‘a ritual re-enactment [...] of writing.’⁷ Driven to access the gesture, the activity, of writing itself..

“The act of writing is the inevitable result of my being alive”

Darboven’s Studenbuch (Book of Hours, 1991) is, as critic Donald Kusptit wrote, ‘a diary of gestures that unfurled [...] around the exhibition space.’⁸ In this sprawling work of yellow A4 pages filled with undulating ‘u’s, time – centuries of it – is experienced as monumental, and gestural, duration. Flusser reminds us ‘[the gesture of] writing is one of the ways thought becomes phenomenal’ but writing too makes time phenomenal. The ‘u’s used are the German equivalent of English ampersands: ‘and-and-and’, ad infinitum. Time and gesture flow, undifferentiated, through waves of this interconnected symbol. I summon Clarice Lispector again who wrote ‘I don’t make literature: I simply live in the passing of time.’⁹ Darboven’s ongoing ‘and-and-and’ seeks not to represent time, but mark time spent, time lived and exhaustively worked through, on and on.

R.M. Rilke - Das Studenbuch Leo Castelli, 1987. Hanne Darboven.

Marks in space and on surfaces indeed ‘mark time’, like the prophetic prisoner who inscribes tallies on the wall,or like I, in my teenage diary, who would log looks from crushes and endless days until summer holidays. The original Book of Hours similarly inscribed time onto surface, the liturgical text designating a temporal cycle of devotions and recitals across the eight canonical hours of the day. If, as Sam Lewitt surmised, ‘Darboven’s life project was to record and reconfigure the possibilities for expressing the movement of time as writing’, I’d add that her project recorded the movement of gesture in time through writing.¹⁰

Darboven’s proclivity toward copying, transcribing and repetition were not, as many have seen them, self-effacing acts of estrangement. In spending her time writing, Darboven was simultaneously writing herself into the work. In a 1989 interview with writer Isabelle Graw, Darboven explained she was ‘rewriting things by hand in order to convey [herself] through the mediation of the experience.’¹¹ The resulting work is entirely subjective, her identity being both invented and inscribed through the act of writing. ‘The act of writing’, Lispector said, ‘is the inevitable result of my being alive.’¹²

Writing is the trace of a once present gesture, a mark in space – announcing presence, thought, time – created by an action in space. The gesture of writing, a monument to moments of living.

¹ Jacques Derrida, Limited Inc (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1988), 8

² Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000) 59

³ Brian Eno and John Cale, “Spinning Away”, Wrong Way Up (Opal/Warner Bros, 1990)

⁴ Darboven quoted in Miriam Schoofs, “Hanne Darboven”, Flash Art (Online, 14th November, 2014)

⁵ Hanne Darboven and Coosje Van Bruggen, “TODAY CROSSED OUT, A PROJECT FOR ARTFORUM”, Artforum, vol. 25, no.5 (1988)

⁶ Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World, trans. by Giovanni Ponteiro (Manchester: Carcanet, 1992) 135

⁷ Briony Fer, The Infinite Line: Re-Making Art after Modernism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) 205

⁸ Donald Kuspit, “Hanne Darboven”, Artforum, vol.32, no.2 (1993)

⁹ Clarice Lispector, A Breath of Life, trans. by Johnny Lorenz (New York: New Directions, 2012) 7

¹⁰ Sam Lewitt in Stephen Hoban, Kelly Kivland, Katherine Atkins (eds.) Artists on Hanne Darboven (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 2016) 62

¹¹ See Graw in Miriam Schoofs, Joâo Fernandes (eds.),The Order of Time and Things: The Home-Studio of Hanne Darboven (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2014) 23

¹² Clarice Lispector, A Breath of Life, 7

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer, researcher and editor. She is the co-founding editor of motor dance journal.

Geometry in the Garden Pt. 3

Peter Newman July 23, 2024

A pathway is the opposite of a grid. In culture, the path is one of the most prevailing life metaphors. It is the spatialization of a story, as we move from one event to the next. Walking a path in a garden is like living in a frame within a frame, a fractal of time on a much larger journey. Like most rock gardens, time moves slower here. The sense of everything in its right place feels generous and liberating. All has been taken care of — you are free to wander…

Hanbe Garden, Mirei Shigemori 1970.

Peter Newman July 23, 2024

In the west of Japan, the Hanbe Garden is one of Shigemori’s less-known works and was completed in 1970 when he was seventy-four years old. It contains an intricately structured pathway that loops through the garden. Along the way are monoliths, inclines, vantage points, bridges, fish ponds, stepping stones, islands and a waterfall. On a plateau, some checkered paving from which a line of diagonal squares leads further.

A pathway is the opposite of a grid. In culture, the path is one of the most prevailing life metaphors. The spatialization of a story, as we move from one event to the next. Walking a path in a garden is living in a frame within a frame, a fractal of time on a much larger journey. Like most rock gardens, time moves slower here. The sense of everything in its right place feels generous and liberating. All has been taken care of — you are free to wander.

Mitaki Temple. Mirei Shigemori 1965

Shigemori created another garden a few years earlier in 1965 at the Mitaki Temple, built on a hillside on the other side of the city, not far from the centre. Among dense foliage, a two-tiered waterfall cascades down to a glade and into a pond, across which substantial stone bridges are placed. Rising from the water is a symmetrical rock triangle. Watching over the garden is a group of standing stones, like prehistoric elders. The garden is completely timeless, it feels like it could have been sleeping for a thousand years, or much longer. That it seems so is magical.

Between the Hakone Mountains and overlooking Sagami Bay, is the Enoura Observatory created by Hiroshi Sugimoto, which opened in 2017. Founded on the principle that Japanese culture is rooted in the art of living in harmony with nature, it aims to reconnect visually and mentally with the oldest of human memories. Enoura features a range of architectural styles from medieval to contemporary, much of it aligned with the movement of the sun.

There is a recreation of a ruined Roman amphitheatre, encircling a stage with the sea as a backdrop. The stage is made from optical glass supported by a wooden lattice, appearing to the audience as to be floating on water. Once a year it will be naturally illuminated from beneath, as the sun enters the glass planks which point out to sea. Close by, a narrow walkway juts out from the landscape towards the horizon, as if a springboard into the void.

Bamboo Grove. Enora Observatory. Hiroshi Sugimoto 2017

The gallery is built with Oya stone, the same textured volcanic rock used by Frank Lloyd Wright for the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. The space is 100 metres long and 100 metres above the sea. Built in line with the axis of the sun, on the summer solstice light will travel gradually across the space from one end to the other, as the day begins.

There are many wonders here. A strolling garden through the landscape, in which a bamboo grove stands in perfect contrast to the horizontal seascapes, for which the artist is famous. A cabin filled with fossils from under the sea. A tea pavilion, with an optical glass rock on which to step through the square nijiriguchi door, a feature of traditional teahouses that require visitors to crawl childlike in humility if they wish to enter. At dawn on the spring and autumn equinoxes, light shines through this door and the glass step glints in the sun.

Winter Solstice Light-Worship Tunnel. Enora Observatory. Hiroshi Sugimoto 2017

One of the most dramatic features of Enoura is the 70-metre tunnel pathway, which cuts through the ground beneath the gallery, emerging on the other side. On the winter solstice, light passes through the tunnel to illuminate a circular stone, in a ring of seating rocks. The solstice is an event celebrated by ancient cultures around the world, as a turning point in the cycle of death and rebirth. The tunnel is dark and made of steel, with a resting space lit by a light well halfway through. As you reach the other side, you come to a rectangular portal framing a view of the ocean and sky. ‘The sea, as people in ancient times would have seen it’, according to the artist. A perspective of time that naturally lends itself to reflections on mortality and the brevity of any single lifetime. ‘Yes, we disappear, but we don’t disappear into a world where there is nothing. My feeling is we return to a place where our life force is kept in storage for a while.’ says Sugimoto.

‘…she knelt down and looked along the passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw. How she longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and those cool fountains…’¹

All photography by Peter Newman.

¹ Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. 1865 Lewis Caroll.

Peter Newman is an artist. There are two permanent installations of his Skystation works in London, at Nine Elms and Canary Wharf.

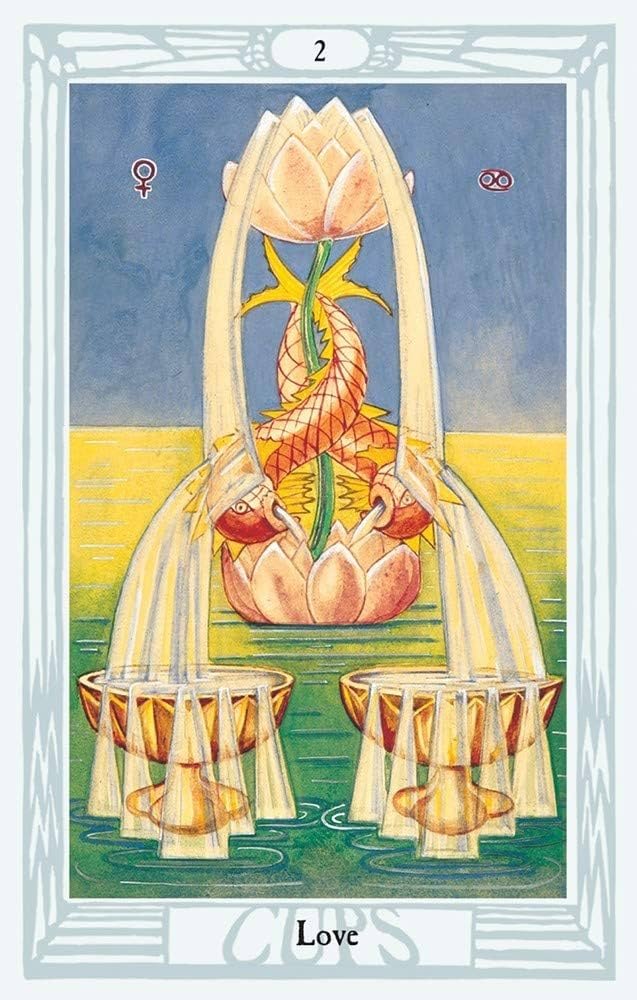

The Two of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel July 20, 2024

The Two of Cups is a card of love and the energetic union between two beings. It pertains to all matters of shared pleasure, mutual growth, and emotional experience - a human alchemy…

Name: Love, the Two of Cups

Number: 2

Astrology: Venus in Cancer

Qabalah: Chokmah of He

Chris Gabriel July 20, 2024

The Two of Cups is a card of love and the energetic union between two beings. It pertains to all matters of shared pleasure, mutual growth, and emotional experience - a human alchemy.

In Rider, we have two lovers holding their cups. Between them there is a surreal caduceus, spiralling snakes culminating in a winged lion head. The lovers are well dressed and crowned with laurels and flowers, standing in front of a pastoral scene.

In Thoth, we have two cups overflowing with water received from a lotus fountain, around which two fish are entwined. This card is Venus in Cancer, a personal, deeply intimate love. We have the greens of Venus, and the blues and amber of Cancer.

In Marseille, we have a uniquely symbolic major arcana. Here the two cups are secondary to the brilliant, alchemical scene. Underground, two angels work at an alembic containing a phoenix. Rising from this alembic, a flower sprouts another flower with fish heads as its leaves. Quite the scene! Through Qabalah, we are given the key to its name: the Queen’s Wisdom. The Queen’s Wisdom is Love.

We have many shared motifs between these cards, all of which point to the joy of love, and the energies at play within. This is when a relationship is ‘in its element’, like a fish in water.

As for the alchemical motifs, all alchemical philosophies are centered on human love as a vessel and metaphor for divine transformation. Alchemy is the Chemical Wedding, a motif we will see depicted in the Thoth deck when the Lovers VI are transmuted into one being in Art XIV.

We can see the cosmic spiralling of love directly in the work of a modern alchemist, Wilhelm Reich. A student of Sigmund Freud, Reich became increasingly far out in his vision of sexuality, moving from psychology and scientific study into mystical visions that perfectly mirror the esoteric traditions.

To Reich the sexual relationship is a product of literal spiraling cosmic energies. A motif which is clearly present in the Two of Cups.

Let us turn to the fish, present in both Marseille and Thoth. The image of a fish as related to Love calls to mind one of my favorite Grimm’s fairy tales, the Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was.

The story follows the misadventures of a boy, cast out by his father for his idiocy, and told to learn how to shudder. He finds the task quite impossible, even when faced with corpses, phantasmagorias, demons and a haunted castle. After overcoming these trials, marrying the Princess, and becoming King, he is still sad, as he can not shudder. His wife, in her wisdom, hatches a plan. It goes as follows:

“At night when the young king was sleeping, his wife was to draw the

clothes off him and empty the bucketful of cold water with the

gudgeons in it over him, so that the little fishes would sprawl about

him. Then he woke up and cried

'oh, what makes me shudder so. - What makes me shudder so, dear wife.

Ah. Now I know what it is to shudder.'

The End”

This Queen’s Wisdom is clearly that of the Two of Cups. That shuddering, as Freud knew well, is not always what one does in fear, but in love and pleasure, which the fairy tale is alluding to.

When pulling this card, we are asked to consider the union of love, forming that union, or giving energy to one we are in. To take joy in our pleasure, and to let it grow, and spring into something divine!

Sacred Geometry and White Magic

Flora Knight July 18, 2024

Sacred geometry, the concept that divine mathematical patterns underpin the universe, has profoundly influenced various religious and mystical traditions. It is rooted in the idea that God is the ultimate mathematician and that the mathematical patterns observed in nature are signs of divinity…

A detail from Hirschvogel’s ‘Geometria’ (1543).

Flora Knight July 18, 2024

Sacred geometry, the concept that divine mathematical patterns underpin the universe, has profoundly influenced various religious and mystical traditions. It is rooted in the idea that God is the ultimate mathematician and that the mathematical patterns observed in nature are signs of divinity. These sacred patterns manifest in numerous ways, such as mandalas, religious architecture, and symbols across Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism. Yet in witchcraft, it is the pentagram that has been most prevalent. Alongside its other interpretations, the pentagram embodies the principles of sacred geometry, a cohesive and balanced symbol, simple, repeatable and divine.

White Magic has long been fascinated with sacred geometry, particularly drawing inspiration from the Temple of Solomon’s design. This structure has significantly influenced the geometric architecture in witchcraft. The intricate designs and patterns seen in the Temple of Solomon have become a cornerstone for many later structures, reflecting the importance of geometry in magical practices and teachings. Various white magical institutions have adopted these geometric principles as a core part of their teachings, emphasizing the connection between spirituality and mathematics.

The caretaker at Newgrange, 1910.

One significant site that highlights the importance of sacred geometry is Bru’gh na Bo’inne, or New Grange, in Ireland. This ancient burial site, one of the oldest Western structures, dates back to ancient history and served as a burial place for Irish kings. New Grange incorporates sacred spirals in its design, which were later espoused by Fibonacci. The entrance of this structure features right-hand spirals, known as Deosil, which are used by priestesses when casting a holy circle. This counter-clockwise movement symbolizes holiness and positive energy. As one progresses through the corridors, the spirals shift to a clockwise direction, known as widdershins, which represents movement away from goodness and aligns with the sun's movement. Each chamber within New Grange symbolizes one of the three worlds of Celtic magic: the sky world, the middle world, and the underworld. This structure parallels the Temple of Solomon in its representation of the fourfold nature of the universe.

Beyond architectural marvels, sacred geometry finds its application in geomancy, a form of divination that became widespread in medieval Europe. Originating from Arabic and Persian traditions, geomancy involves interpreting patterns formed by tossing earth or stones onto the ground or making marks in the sand. By the medieval period, geomancers began using pen and ink to draw random lines of points, creating a Geomantic tableau. This method of divination became second in importance only to astrology during the Middle Ages.

Symbols of Geomancy.