The Queen of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 31, 2024

The Queen of Wands is a court card, and the second highest in the suit of Wands. In each iteration we find our Queen, enrobed, crowned, and bearing a Wand. This is a card of aggression and desire...

Name: Queen of Wands

Astrology: Aries, Water of Fire

Qabalah: He ה of Yod י

Chris Gabriel August 31, 2024

The Queen of Wands is a court card, and the second highest in the suit of Wands. In each iteration we find our Queen, enrobed, crowned, and bearing a Wand. This is a card of aggression and desire.

In Marseille, we find the Queen looking down, her golden wand’s base in her lap, a symbolic phallus. Her long hair and robes flow about her. Both of her hands are at her waist.

In Rider, we find the Queen on a throne adorned with lions. Her right hand bears her wands and her left a Sunflower. Below her stage sits a little black cat. She is a young woman with a demure gaze.

In Thoth, we find the Queen inflamed. Her hair is made of fire that give way to the flames all around her. She looks directly down. Her crown is topped by a hawk, and her wand by a pinecone. She is petting a cheetah.

The Queen of Wands is a card of duality - fire and water, aggression and love, innocence and experience.

A phrase that comes to mind is “Cute Aggression”, the urge to squeeze and bite cute things without actually wanting to cause harm. It’s a confusion of two drives, maternal love and aggression. This is the nature of the Queen of Wands, the struggle between these drives.

Aries is the first sign and known as the “baby of the zodiac”, it is just learning how to exist. Kittens bite and scratch, without any malice, in acts of innocent violence: this is the domain of the Queen of Wands. Animal aggression can be read as the Saturnian child devouring drive, or as the innocent violence of Aries. One wants to maintain power, while the other is trying to gain power.

This follows with the twin of violence, sex. The development of sexuality through aggression, which appears as teasing and name-calling, is opposed to the aggression that expresses itself sexually.

This is the domain of the Queen of Wands who balances these things in her hands, the wand and the flower, the masculine and the feminine, the phallus and yoni.

This card often can indicate a person, often an Aries, but generally a very dominant woman unafraid to express her opinions.The card is the elemental inverse of the Knight of Cups, who balances water and fire, but chooses confused chastity that keeps his heart pure at the cost of his aggressive will, whereas the Queen of Wands takes on the far more difficult task of approaching the world willfully while fighting to keep her heart pure.

When we pull this card, we are often met with this same dilemma, the balancing of love and will. The Queen is telling us “And whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not unto men;”

Towards Alienation

Arcadia Molinas August 29, 2024

Engaging in an uncomfortable reading practice, favouring ‘foreignization’, has the potential to expand our subjectivities and lead us to embrace the cultural other instead of rejecting it. In this walk away from fluency, we find ourselves heading towards alienation. But what does it mean to be alienated as a reader, how does it feel, and perhaps most importantly, how does it happen?

Interessenspharen, 1979. Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt.

Arcadia Molinas August 29, 2024

Last time, translator Lawrence Venuti and philosopher Friedreich Schleirmacher showed us the radical potential of walking away from fluency when reading books in translation. Engaging in an uncomfortable reading practice, they argued, favouring ‘foreignization’, has the potential to expand our subjectivities and lead us to embrace the cultural other instead of rejecting it. In this walk away from fluency, we find ourselves heading towards alienation. But what does it mean to be alienated as a reader, how does it feel, and perhaps most importantly, how does it happen?

The concept of culturemes can help us get closer to an understanding of alienation. Culturemes are social phenomena that have meaning to members of one culture but not to another, so that when they are compared to a corresponding phenomenon in another culture, they are revealed to be specific to only the first culture. They can have an ingrained historical, social or geographical relevance that can result in misconceptions or misunderstandings when being translated. This includes jokes, folklore, idioms, religion or expressions. If we pay attention to the translation of culturemes, we can evaluate how alienation is functioning in the translated text and sketch the contours of its effect on the reader.

Panza de Burro by Andrea Abreu made my body come alive from just one sitting. Even in its original Spanish, the book is alienating. Abreu takes us into the mind of her ten-year old narrator, nicknamed “Shit”, as she spends a warm, cloudy summer in a working-class neighbourhood of Tenerife with her best friend Isora. The language is mercilessly juvenile, deliciously phonetic and profoundly Canarian. The Canarian accent, more like the Venezuelan or Cuban accents of Latin America than a mainland Spanish accent, is emulated in a way similar to what Irvine Welsh does for the Scots dialect in Trainspotting. This means, for example, that a lot of the ends of words are cut off, “usted” becomes “usté”, “nada más” becomes “namás”. On top of this are all the Canarian idiosyncrasies that Abreu employs to paint a vivid sense of place: the food, the weather, the games the children play. Abreu demands her reader move towards her characters, their language, their codes and their culture and with it demands a somatic response from her reader. The translation of such a book should be a fertile ground for the experience of alienation, done two-fold.

“Meeting halfway is a political act that not only allows people to exist at the frontier but brings everyone closer to the frontier too.”

Widening, 1980. Ruth Wolf-Rehfeltd.

On the first page of Panza de Burro, Shit and Isora are eating snacks and sweets at a birthday party, “munchitos, risketos, gusanitos, conguitos, cubanitos, sangüi, rosquetitos de limón, suspiritos, fanta, clipper, sevená, juguito piña, juguito manzana”. Most of these will be familiar to anyone who has grown up in Spain, including the intentional spelling mistakes (“sevená” for example is meant to emulate the Canarian pronunciation of 7-Up). Julia Sanches, in her translation, Dogs of Summer, writes “There were munchitos potato chips, cheese doodles and Gusanitos cheese puffs. There were Conguitos chocolate sweets, cubanitos wafers and sarnies. There were lemon donuts and tiny meringues, orange Fanta, strawberry pop, 7-Up, apple juice and pineapple juice”. The alienating words are still present in the translation, munchitos, gusanitos, conguitos, their rhythm, their sound, carry an echo of their cultural significance and with them maintain the sticky, childish essence of the Canarian birthday party. They are there to flood your senses, which is what, at its best, alienation can hope to do. Yet the words themselves, the look of them, the sound of them, could have also done their infantilizing, somatic job of taking us into the soda pop-flavoured heart of the birthday party taking place on a muggy Canarian day without their tagging English accompaniment “cheese puffs”. To be able to chew the words around for yourself is essential to experience alienation. To experience the foreign, your mouth must move in ways and shapes hitherto unfamiliar to it. In other instances, however, Sanches keeps Canarian culturemes intact, for example the term of endearment “miniña” is untouched in the translated text, which again with its heavily onomatopoeic sound thrusts the unfamiliar reader into a new context, this time for endearment, and so expands the sounds and shapes of affection and proximity.

Gloria Anzaldúa, feminist and queer scholar, wrote Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, a book which takes the alienating project to its logical extreme. The book is not only an exercise in alienation through language but in alienation through form too. Drawing inspiration from her Chicana identity, an identity inherently at a crossroads between Mexicana and tejana cultures, she advocates for a wider “borderlands culture”, a culture that can represent and hold space for the in-between, the interdisciplinary and the intercontinental. In the preface she explains her project, “The switching of "codes" in this book from English to Castilian Spanish to the North Mexican dialect to Tex-Mex to a sprinkling of Nahuatl to a mixture of all of these, reflects my language, a new language-the language of the Borderlands. There, at the juncture of cultures, languages cross-pollinate and are revitalized; they die and are born. Presently this infant language... this bastard language, Chicano Spanish, is not approved by any society. But we Chicanos no longer feel that we need to beg entrance, that we need always to make the first overture –to translate to Anglos, Mexicans and Latinos, apology blurting out of our mouths with every step. Today we ask to be met halfway. This book is our invitation to you-from the new mestizas.”

Anzaldúa wrote a guide on how to live on the borderlands, how to embrace linguistic and cultural hybridity, supporting Venuti and Schleirmacher’s claim that a wider acceptance of difference, of meeting halfway, is a political act that not only allows people to exist at the frontier, but brings everyone closer to the frontier too. Being on the frontier means going towards alienation, it means offering your body to new expressions and new experiences, it is to remain open, to walk on the border like a tightrope, to feel the tension in your muscles from the balance and to come out taught at the other end.

Arcadia Molinas is a writer, editor, and translator from Madrid. She currently works as the online editor of Worms Magazine and has published a Spanish translation of Virginia Woolf’s diaries with Funambulista.

Music Lover’s Field Companion

John Cage August 27, 2024

I have come to the conclusion that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom. For this purpose I have recently moved to the country. Much of my time is spent poring over "field companions on fungi. These I obtain at half price in second-hand bookshops, which latter are in some rare cases next door to shops selling dog-eared sheets of music, such an occurrence being greeted by me as irrefutable evidence that I am on the right track...

Artwork by Lois Long, for John Cage’s 'Mushroom Book' 1972.

John Cage August 27 2024

I have come to the conclusion that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom. For this purpose I have recently moved to the country. Much of my time is spent poring over "field companions on fungi. These I obtain at half price in second-hand bookshops, which latter are in some rare cases next door to shops selling dog-eared sheets of music, such an occurrence being greeted by me as irrefutable evidence that I am on the right track.

The winter for mushrooms, as for music, is a most sorry season. Only in caves and houses where matters of temperature and humidity, and in concert halls where matters of trusteeship and box office are under constant surveillance, do the vulgar and accepted forms thrive. American commercialism has brought about a grand deterioration of the Psalliota campestris, affecting through exports even the European market. As a demanding gourmet sees but does not purchase the marketed mushroom, so a lively musician reads from time to time the announcements of concerts and stays quietly at home. If, energetically, Collybia velutipes should fruit in January, it is a rare event, and happening on it while stalking in a forest is almost beyond one's dearest expectations, just as it is exciting in New York to note that the number of people attending a winter concert requiring the use of one's faculties is on the upswing (1954: 129 out of l2,000,000; 1955: 136 out of 12,000,000).

In the summer, matters are different. Some three thousand different mushrooms are thriving in abundance, and right and left there are Festivals of Contemporary Music. It is to be regretted, however, that the consolidation of the acquisitions of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, currently in vogue, has not produced a single new mushroom. Mycologists are aware that in the present fungous abundance, such as it is, the dangerous Amanitas play an extraordinarily large part. Should not program chairmen, and music lovers in general, come the warm months, display some prudence?

I was delighted last fall (for the effects of summer linger on, viz. Donaueschingen, C. D. M. I., etc.) not only to revisit in Paris my friend the composer Pierre Boulez, rue Beautreillis, but also to attend the Exposition du Champignon, rue de Buffon. A week later in Cologne, from my vantage point in a glass-encased control booth, I noticed an audience dozing off, throwing, as it were, caution to the winds, though present at a loud-speaker emitted program of Elektronische Musik. I could not help recalling the riveted attention accorded another loud-speaker, rue de Buffon, which delivered on the hour a lecture describing mortally poisonous mushrooms and means for their identification.

“The second movement was extremely dramatic, beginning with the sounds of a buck and a doe leaping up to within ten feet of my rocky podium. The expressivity of this movement was not only dramatic but unusually sad from my point of view, for the animals were frightened simply because I was a human being.”

John Cage and Lois Long.

But enough of the contemporary musical scene; it is well known. More important is to determine what are the problems confronting the contemporary mushroom. To begin with, I propose that it should be determined which sounds further the growth of which mushrooms; whether these latter, indeed, make sounds of their own; whether the gills of certain mushrooms are employed by appropriately small-winged insects for the production of pizzicati and the tubes of the Boleti by minute burrowing ones as wind instruments; whether the spores, which in size and shape are extraordinarily various, and in number countless, do not on dropping to the earth produce gamelan-like sonorities; and finally, whether all this enterprising activity which I suspect delicately exists, could not, through technological means, be brought, amplified and magnified, into our theatres with the net result of making our entertainments more interesting.

What a boon it would be for the recording industry (now part of America'. sixth largest) if it could be shown that the performance, while at table, of an LP of Beethoven's Quartet Opus Such-and-Such so alters the chemical nature of Amanita muscaria as to render it both digestible and delicious!

Lest I be found frivolous and light-headed and, worse, an "impurist" for having brought about the marriage of the agaric with Euterpe, observe that composers are continually mixing up music with something else. Karlheinz Stockhausen is clearly interested in music and juggling, constructing as he does "global structures," which can be of service only when tossed in the air; while my friend Pierre Boulez, as he revealed in a recent article (Nouvelle Revue Française, November 1954), is interested in music and parentheses and italics! This combination of interests seems to me excessive in number. I prefer my own choice of the mushroom. Furthermore it is avant-garde.

I have spent many pleasant hours in the woods conducting performances of my silent piece~ transcriptions, that is, for an audience of myself, since they were much longer than the popular length which I have had published. At one performance, I passed the first movement by attempting the identification of a mushroom which remained successfully unidentified. The second movement was extremely dramatic, beginning with the sounds of a buck and a doe leaping up to within ten feet of my rocky podium. The expressivity of this movement was not only dramatic but unusually sad from my point of view, for the animals were frightened simply because I was a human being. However, they left hesitatingly and fittingly within the structure of the work. The third movement was a return to the theme of the first, but with all those profound, so-well-known alterations of world feeling associated by German tradition with the A-B-A.

In the space that remains, I would like to emphasize that I am not interested in the relationships between sounds and mushrooms any more than I am in those between sounds and other sounds. These would involve an introduction of logic that is not only out of place in the world, but time consuming. We exist in a situation demanding greater earnestness, as I can testify, since recently I was hospitalized after having cooked and eaten experimentally some Spathyema foetida, commonly known as skunk cabbage. My blood pressure went down to fifty, stomach was pumped, etc. It behooves us therefore to see each thing directly as it is, be it the sound of a tin whistle or the elegant Lepiota procera.

John Cage was an American composer, writer, music theorist and amateur mycologist. He was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde and amongst the most consequential and important composers of the 20th Century.

The Emperor (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 24, 2024

The Emperor is the beginning of the Tarot’s journey through the Zodiac, and it starts, as with ‘The Canterbury Tales’, when “the yonge sonne hath in the Ram his half cours yronne”. This is a card of paternal, masculine power. In each iteration we see the Emperor crowned, enthroned, and bearing a scepter…

Name: The Emperor

Number: IV

Astrology: Aries

Qabalah: Tzaddi

Chris Gabriel August 24, 2024

The Emperor is the beginning of the Tarot’s journey through the Zodiac, and it starts, as with ‘The Canterbury Tales’, when “the yonge sonne hath in the Ram his half cours yronne”. This is a card of paternal, masculine power. In each iteration we see the Emperor crowned, enthroned, and bearing a scepter.

In Rider, we find an aged Emperor with a long white beard and a deep red cloak covering his armor. He is facing ahead. His scepter is a ‘crux ansata’, a variation on the Ankh of the Egyptians, that is a symbol of the whole of things (0, the Creative Nothing and “+” the Cross as Four elements), for this is the King of the World. In his other hand is a globe of gold. His throne has four ram heads. The background is made up of fiery mountains.

In Thoth, we find the Emperor depicted entirely with a fiery palette. He has a shorter beard, and a tunic bearing symbols of his dominion. The Bee is of particular interest here, serving as a symbol of natural hierarchy. His scepter bears the head of a ram, and his globe is in the form of Boehme’s Globus Cruciger. A shield depicting a double Phoenix lays at his feet alongside a sheep with a flag. Behind him are two large rams. Unlike the Rider Emperor, he has crossed legs, this posture, along with his arms form the Alchemical sign of Sulphur.

In Marseille, we once again find the Emperor older, with gray hair and a beard. He has a golden cross necklace, a crown that appears like fire, and a scepter bearing the Globus Cruciger. A shield bearing an eagle lays at his cross feet.

The Emperor is the card of the Good King, the good father, the righteous power in Man, not a wicked king, or an unjust ruler. This is a King Arthur, the one who is powerful by nature. The Bee in Thoth is a symbol shared with the Empress, the Lovers, and Art. Together they form an alchemical narrative, a Chymical Wedding. Bees form beautiful geometric hives, and unlike wasps, they give sweet honey. This is the ideal form of hierarchy, one that is natural and bears great fruits for all.

Explainer of Boehme’s Globus Cruciger.

As Aries is the first sign, we see the Emperor is primus inter pares, first among equals. Aries is the ‘baby of the zodiac’, and like Arthur is given rulership very early on. Aries the Ram uses his horns to force his way through, though his horns protect him, his butting head causes a tremendous shock.

This too is the nature of a King - if they are ‘Great’ in the historical sense, they are not easy on those around them. Great Kings are terrible cataclysms. The Globus Cruciger that he bears, according to the alchemist Jakob Boehme, is the image of lightning striking the world. And the yogic posture, which forms Sulphur, is an ideogram constituted by a simple stick figure crowned by fire, a fiery man.

The Emperor is like a Ram that makes sparks with each thrust of his horns, and sets himself aflame. In old stories, we like to see a young person gain the mandate of Heaven and go to war, fighting their way to the top and then wielding tough but just judgment. In our day to day lives however, this may not be the case.

As we bring the scale of this card down, we find the Father, the masculine man, and while the divine fire is in the righteous, this is a figure that can be ill dignified and, if not checked, become a tyrant, an arrogant aggressive man who believes in his own superiority.

Yogic posture ideogram.

This is where Aries' opposition to Libra comes in handy. It is what Crowley saw as “Love and Will” and, even further, the idea that Love is the Law. If the King’s law is not Love, then he is unjust, an overabundance of the aggressive Aries without the balance of Libra’s scales.

The balance of these energies makes a great King and an even greater Father. Paternal authority should be reserved entirely to keep his Kingdom, his home at peace and loving, not to tyrannize those he rules.

When the Emperor is pulled in a reading, I find it tends to relate directly to a Father, or to a position of authority. This can be someone’s literal father or a father figure, or a position they are in or want to be in. It can also simply indicate the energy of Aries.

I Am For An Art… (1961)

Claes Oldenburg August 22, 2024

I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.

I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all, an art given the chance of having a starting point of zero...

Oldenburg in The Store, 107 East Second Street, New York, 1961. Robert R. McElroy.

Claes Oldenburg August 22 2024

I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.

I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all, an art given the chance of having a starting point of zero.

I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap & still comes out on top.

I am for an art that imitates the human, that is comic, if necessary, or violent, or whatever is necessary.

I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself.

I am for an artist who vanishes, turning up in a white cap painting signs or hallways.

I am for art that comes out of a chimney like black hair and scatters in the sky.

I am for art that spills out of an old man's purse when he is bounced off a passing fender.

I am for the art out of a doggy's mouth, falling five stories from the roof.

I am for the art that a kid licks, after peeling away the wrapper. I am for an art that joggles like everyones knees, when the bus traverses an excavation.

I am for art that is smoked, like a cigarette, smells, like a pair of shoes.

I am for art that flaps like a flag, or helps blow noses, like a handkerchief.

Pastry Case, 1961. Claes Oldenburg.

I am for art that is put on and taken off, like pants, which develops holes, like socks, which is eaten, like a piece of pie, or abandoned with great contempt, like a piece of shit.

I am for art covered with bandages, I am for art that limps and rolls and runs and jumps. I am for art that comes in a can or washes up on the shore.

I am for art that coils and grunts like a wrestler. I am for art that sheds hair.

I am for art you can sit on. I am for art you can pick your nose with or stub your toes on.

I am for art from a pocket, from deep channels of the ear, from the edge of a knife, from the corners of the mouth, stuck in the eye or worn on the wrist.

I am for art under the skirts, and the art of pinching cockroaches.

I am for the art of conversation between the sidewalk and a blind mans metal stick.

I am for the art that grows in a pot, that comes down out of the skies at night, like lightning, that hides in the clouds and growls. I am for art that is flipped on and off with a switch.

I am for art that unfolds like a map, that you can squeeze, like your sweetys arm, or kiss, like a pet dog. Which expands and squeaks, like an accordion, which you can spill your dinner on, like an old tablecloth.

I am for an art that you can hammer with, stitch with, sew with, paste with, file with.

I am for an art that tells you the time of day, or where such and such a street is.

I am for an art that helps old ladies across the street.

I am for the art of the washing machine. I am for the art of a government check. I am for the art of last wars raincoat.

I am for the art that comes up in fogs from sewer-holes in winter. I am for the art that splits when you step on a frozen puddle. I am for the worms art inside the apple. I am for the art of sweat that develops between crossed legs.

I am for the art of neck-hair and caked tea-cups, for the art between the tines of restaurant forks, for the odor of boiling dishwater.

I am for the art of sailing on Sunday, and the art of red and white gasoline pumps.

I am for the art of bright blue factory columns and blinking biscuit signs.

I am for the art of cheap plaster and enamel. I am for the art of worn marble and smashed slate. I am for the art of rolling cobblestones and sliding sand. I am for the art of slag and black coal. I am for the art of dead birds.

I am for the art of scratchings in the asphalt, daubing at the walls. I am for the art of bending and kicking metal and breaking glass, and pulling at things to make them fall down.

I am for the art of punching and skinned knees and sat-on bananas. I am for the art of kids' smells. I am for the art of mama-babble.

I am for the art of bar-babble, tooth-picking, beerdrinking, egg-salting, in-suiting. I am for the art of falling off a barstool.

I am for the art of underwear and the art of taxicabs. I am for the art of ice-cream cones dropped on concrete. I am for the majestic art of dog-turds, rising like cathedrals.

I am for the blinking arts, lighting up the night. I am for art falling, splashing, wiggling, jumping, going on and off.

I am for the art of fat truck-tires and black eyes.

Performances at Oldenburg's The Store, 1962. Robert R. McElroy.

I am for Kool-art, 7-UP art, Pepsi-art, Sunshine art, 39 cents art, 15 cents art, Vatronol art, Dro-bomb art, Vam art, Menthol art, L & M art, Ex-lax art, Venida art, Heaven Hill art, Pamryl art, San-o-med art, Rx art, 9.99 art, Now art, New art, How art, Fire sale art, Last Chance art, Only art, Diamond art, Tomorrow art, Franks art, Ducks art, Meat-o-rama art.

I am for the art of bread wet by rain. I am for the rat's dance between floors.

I am for the art of flies walking on a slick pear in the electric light. I am for the art of soggy onions and firm green shoots. I am for the art of clicking among the nuts when the roaches come and go. I am for the brown sad art of rotting apples.

I am for the art of meowls and clatter of cats and for the art of their dumb electric eyes.

I am for the white art of refrigerators and their muscular openings and closings.

I am for the art of rust and mold. I am for the art of hearts, funeral hearts or sweetheart hearts, full of nougat. I am for the art of worn meathooks and singing barrels of red, white, blue and yellow meat.

I am for the art of things lost or thrown away, coming home from school. I am for the art of cock-and-ball trees and flying cows and the noise of rectangles and squares. I am for the art of crayons and weak grey pencil-lead, and grainy wash and sticky oil paint, and the art of windshield wipers and the art of the finger on a cold window, on dusty steel or in the bubbles on the sides of a bathtub.

I am for the art of teddy-bears and guns and decapitated rabbits, exploded umbrellas, raped beds, chairs with their brown bones broken, burning trees, firecracker ends, chicken bones, pigeon bones and boxes with men sleeping in them.

I am for the art of slightly rotten funeral flowers, hung bloody rabbits and wrinkly yellow chickens, bass drums & tambourines, and plastic phonographs. I am for the art of abandoned boxes, tied like pharaohs. I am for an art of watertanks and speeding clouds and flapping shades.

I am for U.S. Government Inspected Art, Grade A art, Regular Price art, Yellow Ripe art, Extra Fancy art, Ready-to-eat art, Best-for-less art, Ready-tocook art, Fully cleaned art, Spend Less art, Eat Better art, Ham art, pork art, chicken art, tomato art, banana art, apple art, turkey art, cake art, cookie art.

add:

I am for an art that is combed down, that is hung from each ear, that is laid on the lips and under the eyes, that is shaved from the legs, that is brushed on the teeth, that is fixed on the thighs, that is slipped on the foot.

square which becomes blobby

Claes Oldenburg, 1929 – 2022, was a Swedish-born American sculptor best known for his public art installations, typically featuring large replicas of everyday objects. In 1961 he opened The Store in Downtown New York which hosted performances, conceptual art pieces and happenings, as well as selling work he made in the space to punters and passerbys, removing the middle-man from the commercialisation of the art world. He wrote this text for an exhibition catalogue in 1961, reworked it when he opened the store and then republished it again in 1970 for an exhibition in London, from which this version is taken.

Mystery and Creation (1928)

Giorgio de Chirico August 20, 2024

To become truly immortal a work of art must escape all human limits: logic and common sense will only interfere. But once these barriers are broken it will enter the regions of childhood vision and dream.

Piazza D'Italia, 1964. Giorgio de Chirico.

Giorgio de Chirico August 20 2024

To become truly immortal a work of art must escape all human limits: logic and common sense will only interfere. But once these barriers are broken it will enter the regions of childhood vision and dream.

Profound statements must be drawn by the artist from the most secret recesses of his being; there no murmuring torrent, no birdsong, no rustle of leaves can distract him.

What I hear is valueless; only what I see is living, and when I close my eyes my vision is even more powerful. It is most important that we should rid art of all that it has contained of recognizable material to date, all familiar subject matter, all traditional ideas, all popular symbols must be banished forthwith. More important still, we must hold enormous faith in ourselves: it is essential that the revelation we receive, the conception of an image which embraces a certain thing, which has no sense in itself, which has no subject, which means absolutely nothing from the logical point of view, I repeat, it is essential that such a revelation or conception should speak so strongly in us, evoke such agony or joy, that we feel compelled to paint, compelled by an impulse even more urgent than the hungry desperation which drives a man to tearing at a piece of bread like a savage beast.

I remember one vivid winter's day at Versailles. Silence and calm reigned supreme. Everything gazed at me with mysterious, questioning eyes. And then I realized that every corner of the palace, every column, every window possessed a spirit, an impenetrable soul. I looked around at the marble heroes, motionless in the lucid air, beneath the frozen rays of that winter sun which pours down on us without love, like perfect song. A bird was warbling in a window cage. At that moment I grew aware of the mystery which urges men to create certain strange forms. And the creation appeared more extraordinary than the creators. Perhaps the most amazing sensation passed on to us by prehistoric man is that of presentiment. It will always continue. We might consider it as an eternal proof of the irrationality of the universe. Original man must have wandered through a world full of uncanny signs. He must have trembled at each step.

Giorgio de Chirico was an Italian artist and writer born in 1888, who founded the movement of Metaphysical Painting. He was inspired by Neitzsche and Shopenhauer in his philosophy, that informed both his visual and written work, and his own writing was a major source of inspiration to Andre Breton and the Surrealist Movement. This essay was first published in 1928 by Breton in ‘Surrealism and Painting’.

Five of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 17, 2024

The Five of Swords is a card of undoing, of our dreams that come crashing down. Here the Swords which have been gently building start to fall apart like a house of cards. This is the representation of a failed hypothesis...

Name: Defeat, the Five of Swords

Number: 5

Astrology: Air, Venus in Aquarius

Qabalah: Gevurah of Vau

Chris Gabriel August 17, 2024

The Five of Swords is a card of undoing, of our dreams that come crashing down. Here the Swords which have been gently building start to fall apart like a house of cards. This is the representation of a failed hypothesis.

In Rider, we find a smiling rogue picking up swords that have been lost in battle. Behind him two men mourn before a sea. The sky is cloudy. Two swords lay on the ground, and three are in hand. He is picking up the pieces, unmoved by what has occurred.

In Thoth, we find a reversed pentagram, a falling star made of chipped swords. Geometric figures sputter about it with falling petals. The card has the violet of Aquarius and the Green of Venus. Venus in Aquarius has dreams and desires, but lacks the grounding to actualize them, creating a distance and alienation.

In Marseille, we have a single central sword whose tip is weaving through the four arched around it. Through Qabalah, we find it signifies “The Anger of the Prince”.

The Anger of the Prince is Defeat. It is an anger toward reality, after his expectations, measurements, methods and plans were undone..

This is not defeat at the hands of another, but self undoing.

My great grandfather was a Mason, and a piece of advice he gave me was to “measure twice, cut once”.This card occurs as a result of incorrect measurements. We can imagine a car stranded out of gas on the side of the road, a disappointed couple and an amused tow truck driver taking a modern form of the Rider card..

The suit of Swords pertains to the mental sphere, which is the origin of our many defeats, foibles, expectations, and visions which fall apart when they meet the real world.

Aesop’s Astronomer, who despite his calculations of the stars falls into a well.

While the Five of Wands gives us the image of a tyrannical ruler who weighs too heavily upon his people, the Five of Swords is the image of a totally removed ruler, like Marie Antoinette, who when told that the peasants had no bread, replied: "Then let them eat cake."

While we often attribute the ‘airheadedness' of these dynamics to an ‘overdeveloped imagination’, it is in fact a failure of imagination.

It makes me think of how so many want to make art, only they need millions of dollars, expensive equipment, and the like, while the truly great artists find a way to bring their vision into reality with what they have in hand. They set aside unreal expectations for the sake of the art itself. Which requires more imagination?

The great thing about this card is that it functions as a prerequisite for the Six of Swords, which represents Science. These are the failed hypotheses, the experiments gone awry, the countless mistakes that are needed to develop a functional methodology.

When we pull this card, we are being shown a part of ourselves that holds these unreal ideas, illusions that we maintain which will be brought tumbling down by the world.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, we can be like the smiling fellow, pick up the pieces and try again. This is how we develop a true understanding of the world.

A Forager’s Take on Fairytales Pt. 1

Izzy Johns August 15, 2024

Long ago in Drumline, County Clare, in the late 19th Century, an old farmer and his wife huddled for warmth in a mud hut. Many a cold winter passed, and finally, the man agreed to build his wife a house of bricks and mortar. He set to work the following Spring. Not a day had passed when the old man received a visit from a traveler, who spoke these words…

Izzy Johns August 15 2024

Long ago in Drumline, County Clare, in the late 19th Century, an old farmer and his wife huddled for warmth in a mud hut. Many a cold winter passed, and finally, the man agreed to build his wife a house of bricks and mortar.

He set to work the following Spring. Not a day had passed when the old man received a visit from a traveler, who spoke these words:

“I wouldn’t build there if I was you. That’s the wrong place. If you build there you won’t be short of company, whatever else.”

The old man paid him no mind, but sure enough, the moment he and his wife lay down to rest in their new home, they were plagued by noise and disruption. Furniture was knocked over, cutlery strewn across the floor, crockery smashed. They couldn’t get a wink of sleep. But, as sure as day, whenever they went to investigate, they found nothing and no one. The old couple sought the help of the local preacher, who recognised this as the work of the Sidhe, the Little Folk of this land. He tried to exorcize the house, but to no avail.

After five sleepless nights, the man wearily set off to the market to sell their cows. It was the Gale day, the day that their rent was due, and money was sparse. English colonisers had seized land from the Irish farmers some years before. Now they were renting it back to them, and the rent was high.

The old man got a fair price for the cows, and he stopped at a roadside pub on the way home. It was there that he encountered the traveler once again. In desperation, the man begged the traveler for advice. He would do anything so that the Little Folk would let him rest. The traveler walked him home, and took him to stand in the yard, on the far side of the house.

He said:

“Now, look out there and tell me what you see.”

[…] “The yard?”

“No,” he says, “look again.”

“The road?”

“No. Look carefully.”

“Oh, that old Whitethorn bush? Sure, that’s there forever. That could be there since the start o’ the world.”

“D’you tell me that now?”

The old man walked out to the gable o’ the house, called [him], then says, “come over here.”

He did.

“Look out there, and tell me what do you see?”

He looked out from that gable end, and there, no farther away than the end o’ the garden, was another Whitethorn bush, standing alone.

“Now,” says the old man, “I told you. I warned you. The fairies’ path is between them bushes and beyond. And you’re after building your house on it.”

Upon the instruction of the traveler, the man built two doors in either side of the house, in line with the Whitethorns. From then on, the Little Folk had a clear passage, and the man and his wife were not bothered again.¹

“The higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view”

British Goblins, 1880. Wirt Sikes.

I was very struck by this account. It feels different to the rich, meandering folk-tale jewels I love so much, that are wrapped in mythos and allegory. Instead, this tale falls into the realm of family and community stories, that are still “lived in”, in this case, by the old couple’s grandson, who told this story to Eddie Lenihan in the living room of the very same house. He said that he still leaves the two doors ajar each night so as to let the fairies pass. There’s no use in locking them, he says, for they’ll only be open again by the morning.

Make no mistake, this story is not hearsay. A book of fairy tales might read like a book of fiction, but it isn’t. What we see in this tale, and so many others like it, is a relic of a complex faith system from times gone by, and it’s important that we storytellers hold it in that way. This story comes from Ireland, where the fairies are called Sídhe, or Sí, though often called by euphemisms to avoid catching their attention. The Sidhe are the descendants of the people of Danu, the Tuatha Dé Danann, a race of fallen Gods and Goddesses that dwell in the liminality between our world and the otherworld, the An Saol Eile. It’s only fair to acknowledge their providence, not least is it a crucial act of cultural preservation.

Fairies have a range of habitats depending on where you are live. In Ireland, they are particularly fond of two places: a lone Whitethorn (Hawthorn) tree, and the forts - those grand, grassy mounds of earth, often covered in a greater diversity of wild plants than their surroundings. In this tale, the old couple has disturbed not a habitat, but a passage between habitats. More savvy builders would have driven four hazel rods into the ground, marking out the proposed foundations of the house. If by the next day any rod had moved, the house should be built elsewhere.

The fairies in this story star in a role that I’ve seen in countless tales; defending their habitat from ecological destruction. Here, they were able to communicate with the intruders and resolve the problem quickly. It’s a good thing that the old couple were forthcoming. Fairies will always give warnings, but it’s perfectly within their power to cause grave suffering if those warnings aren’t heeded. They can be at best didactic and at worst violent, but they have no interest in troubling a person who isn’t troubling them. I can’t condone the violence, but I marvel at how proficient they are at protecting and stewarding the land. Plus, they greatly enrich the ecosystem. Various tales see fairies fertilizing soil for generous farmers, and producing abundances of wildflowers and fungi. It’s said that the rings of mushrooms we see in woodlands and meadows are where they’ve danced.

The Intruder, c.1860. John Anster Fitzgerald.

Thinking about this with an Ecologist’s gaze, fairies are a fascinating species. They might well be a larger genus with loads of regionally-specific variants like small people, spriggans, buccas, elves, bockles and knockers, browneys, goblins, dryads, gnomes and piskies. There’s a wealth of anecdotal evidence of their existence, thousands and thousands of stories, stretching back millenia, yet we’ve never successfully captured and studied them. Perhaps what makes this species most unique is their ability to outwit ours. Their cunning gently prods at our human arrogance, contesting our claim to be the most “developed” of species.

Far less frequently in the UK do we hear tales of the Little Folk interfering with larger property developments. In London, for example, you’ll scarcely come across a piece of land that hasn’t been leveled ten times over, and most Whitethorns are confined to cultivated hedges. I wonder how many forts have been destroyed in my neighborhood. Our lack of understanding of the fairies’ life cycles and physiology makes it pointless to speculate on why larger builds don’t experience ramifications from the little folk. It’s hard not to wonder if heavy machinery, giant crews of contractors and big blocks of hundreds of dwellings haven’t been too much for the fairies to contend with. I hate to think that, unbeknownst to us, urbanization might have wiped them out. If fairies are still around, it’s clear that they’re gravely endangered.

If this is the case, then it makes fairies one of over two million species under threat of extinction. It’d be such a shame if these creatures, these stories, and the feelings that they represent, disappeared altogether. I love this tale for giving us such a tangible example of humans making space for fairies and subsequently managing to co-exist peacefully. The fairies in this story are model land guardians, and from that we humans have a lot to learn.

Izzy Johns is a forager and storyteller. She teaches foraging under the monicker Rights For Weeds and manages the Phytology medicine garden in East London. You can find her work on Substack [rightsforweeds.substack.com] and Instagram [instagram.com/ rightsforweeds] .

¹As recounted to Eddie Lenihan in 2001 by the couple’s grandson, recorded in ‘Meeting the Other Folk…”

Against Fluency

Arcadia Molinas August 13, 2024

Reading is a vice. It is a pleasurable, emotional and intellectual vice. But what distinguishes it from most vices, and relieves it from any association to immoral behaviour, is that it is somatic too, and has the potential to move you…

Guilliaume Apollinaire, 1918. Calligram.

Arcadia Molinas August 13, 2024

Reading is a vice. It is a pleasurable, emotional and intellectual vice. But what distinguishes it from most vices, and relieves it from any association to immoral behaviour, is that it is somatic too, and has the potential to move you. A book can instantly transport you to cities, countries and worlds you’ve never set foot on. A book can take you to new climates, suggest the taste of new foods, introduce you to cultures and confront you with entirely different ways of being. It is a way to move and to travel without ever leaving the comfort of your chair.

Books in translation offer these readerly delights perhaps more readily than their native counterparts. Despite this, the work of translation is vastly overlooked and broadly underappreciated. In book reviews, the critique of the translation itself rarely takes up more than a throwaway line which comments on either the ‘sharpness’ or ‘clumsiness’ of the work. It is uncommon, too, to see the translator’s name on the cover of a book. A good translation, it seems, is meant to feel invisible. But is travelling meant to feel invisible – identical, seamless, homogenous? Or is travelling meant to provoke, cause discomfort, scream its presence in your face? The latter seems to me to be the more somatic, erotic, up in your body experience and thus, more conducive to the moral component of the vice of reading.

French translator Norman Shapiro describes the work of translation as “the attempt to produce a text so transparent that it does not seem to be translated. A good translation is like a pane of glass. You only notice that it’s there when there are little imperfections— scratches, bubbles. Ideally, there shouldn’t be any. It should never call attention to itself.” This view is shared by many: a good translation should show no evidence of the translator, and by consequence, no evidence that there was once another language involved in the first place at all. Fluency, naturalness, is what matters – any presence of the other must be smoothed out. For philosopher Friedreich Schlerimacher however, the matter is something else entirely. For him, “there are only two [methods of translation]. Either the translator leaves the author in peace, as much as possible, and moves the reader towards him; or he leaves the reader in peace, as much as possible, and moves the author towards him.” He goes on to argue for the virtues of the former, for a translation that is visible, that moves the reader’s body and is seen and felt. It’s a matter of ethics for the philosopher – why and how do we translate? These are not minor questions when considering the stakes of erasing the presence of the other. The repercussions of such actions could reflect and accentuate larger cultural attitudes to difference and diversity as a whole.

“The higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view”

Guilliaume Apollinaire, 1918. Calligram.

Lawrence Venuti coins Schlerimacher’s two movements, from reader to author and author to reader, as ‘foreignization’ and ‘domestication’ in his book The Translator’s Invisibility. Foreignization is “leaving the author in peace and moving the reader towards him”, which means reflecting the cultural idiosyncrasies of the original language onto the translated/target one. It means making the translation visible. Domestication is the opposite, it irons out any awkwardness and imperfections caused by linguistic and cultural difference, “leaving the reader in peace and moving the author towards him”. It means making the translation invisible, and is the way translation is so often thought about today. Venuti says the aim of this type of translation is to “bring back a cultural other as the same, the recognizable, even the familiar; and this aim always risks a wholesale domestication of the foreign text, often in highly self- conscious projects, where translation serves an appropriation of foreign cultures for domestic agendas, cultural, economic, political.”

The direction of movement in these two strategies makes all the difference. Foreignization makes you move and travel towards the author, while domestication leaves you alone and doesn’t disturb you. There is, Venuti says, a cost of being undisturbed. He writes of the “partly inevitable” violence of translation when thinking about the process of ironing out differences. When foreign cultures are understood through the lens of a language inscribed with its own codes, and which consequently carry their own embedded ways of regarding other cultures, there is a risk of homogenisation of diversity. “Foreignizing translation in English”, Venuti argues, “can be a form of resistance against ethnocentrism and racism, cultural narcissism and imperialism, in the interests of democratic geopolitical relations.” The potential for this type of reading and of translating is by no means insignificant.

To embrace discomfort then, an uncomfortable practice of reading, is a moral endeavour. To read foreignizing works of translation is to expand one’s subjectivity and suspend one’s unified, blinkered understanding of culture and linguistics. Reading itself is a somatic practice, but to read a work in translation that purposefully alienates, is to travel even further, it’s to go abroad and stroll through foreign lands, feel the climate, chew the food. It’s well acknowledged that the higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view. And to get the bigger picture is as possible to do as sitting on your favourite chair, opening a book and welcoming alienation.

Arcadia Molinas is a writer, editor, and translator from Madrid. She currently works as the online editor of Worms Magazine and has published a Spanish translation of Virginia Woolf’s diaries with Funambulista.

The Ace of Disks (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 10, 2024

The Ace of Disks is the seed of the earthy suit, from it all the disks grow. This is the foundation or cornerstone of an establishment.It is, in some ways, the most important card in the suit, as nothing that lasts can be built on a weak foundation…

Name: Ace of Disks

Number: 1

Astrology: Earth

Qabalah: Kether of He ה

Chris Gabriel August 10, 2024

The Ace of Disks is the seed of the earthy suit, from it all the disks grow. This is the foundation or cornerstone of an establishment.It is, in some ways, the most important card in the suit, as nothing that lasts can be built on a weak foundation.

The image is simple, that of a coin, and flowery growth.

In Rider, we have a divine hand bringing forth a pentacle, a coin bearing the five pointed star. Beneath is a garden and flowery terrace. There is a path leading to distant mountains.

In Thoth, we have a coin bearing a pentagram and a septagram within it. At the center is the personal seal of Crowley, three interlocked circles marked “666” and the Greek around the border reads “To Mega Therion” or “The Great Beast”, this is the autograph of the deck’s creator. Beyond the central coin we have helicopter seeds and verdant imagery.

In Marseille, a flowery coin is depicted with four flowers. Qabalistically, this card is the “Crown of the Princess”: the Princess of the Earth is crowned by a Seed, and crowned by her foundation.

The divine hand of Rider is absent from Marseille, where the hands of God appear only in the Ace of Wands and the Ace of Swords, as those two elements are considered “higher”. The Earth is the lowest element, the most mundane and it is only from this base place that we can reach the highest forces.

It calls to mind Matthew 7:25: And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock.

The Ace of Disks must be the rock of our further exploration. From this foundational anchor we can remain sturdy in the midst of spiritual chaos.

When we say that a loved one is “our rock”, this is the card.

Yet in Thoth, we find the helicopter seed, a moving seed, a seed that flies! Showing us that this foundation need not be literally set in the ground, a true firmness and foundation can move with us, for it comes from within.

When we pull this card, we are being shown a foundation, which can be material, whether it be a place where we can establish our work or where we are able to spiritually flourish. As for money, think of “seed capital”.

This card represents both the necessary energy and the space to build.

Balancing on the Earth

Tuukka Toivonen August 8, 2024

Volumes have been written about how we humans might enter a more balanced relationship with the Earth. Such contributions tend to adopt a disembodied, impersonal perspective, building on a conceptual language removed from our daily experience. What would we discover if we instead approached the question of balance more literally? What new possibilities and inventions might be revealed if we looked anew at how we seek to balance on the Earth, in an embodied sense? And can such a way of thinking lead to a more resonant connection with the ground one stands, walks and dances upon?

Artificiosa Totius Logices Description (1614). Meurisse and Gaultier.

Tuukka Toivonen August 8, 2024

“Be aware of the contact between your feet and the Earth. Walk as if you are kissing the Earth with your feet.” - Thich Nhat Hanh

Volumes have been written about how we humans might enter a more balanced relationship with the Earth. Such contributions tend to adopt a disembodied, impersonal perspective, building on a conceptual language removed from our daily experience. What would we discover if we instead approached the question of balance more literally? What new possibilities and inventions might be revealed if we looked anew at how we seek to balance on the Earth, in an embodied sense? And can such a way of thinking lead to a more resonant connection with the ground one stands, walks and dances upon?

From the moment our lives commence, we begin to manoeuvre our bodies in relation to other beings, to gravity and to the broader physical world that surrounds us, eventually gaining the ability to stand up and walk. As the contemporary German theorist of resonance and societal acceleration Hartmut Rosa suggests, this is precisely where we must start if we are to understand shared human ways of being and relating to the world:

“The most basic and obvious answer to the question ‘How are we situated in the world?’ is simply: on our feet. We stand upon the world. We feel it beneath us. It sustains our weight. The certainty that the ground we stand on will bear us up is among the most fundamental prerequisites of our ontological security. We must be able to depend on it, and we depend on it blindly in the normal course of everyday life. If the ground were to unexpectedly collapse, if the earth opened up beneath us, we would experience this as a shocking event, a traumatic loss of that very security.”¹

Illustration to Emerson’s Nature (c.1838). Christopher Pearse Cranch.

Given that our ability to stand and walk upon supportive ground defines a major part of our existence, it follows that the act of balancing – however unconsciously practised – must also be central to how we exist and situate ourselves within, and in relation to, the world. Without sufficient balancing, there can surely be no consistent experience of ontological security.

Yet, it seems we have unwittingly lost, or at least narrowed, our ability to balance on the Earth as we have adjusted to contemporary styles of living. Could it be that in this process we might have degraded not only our sense of security and confidence – adding to the many anxieties our societies appear currently steeped in – but also our ability to enter into a genuine relationship with the world through our bodies?

We prefer to walk on smooth pavements rather than textured, uneven forest paths. We like to traverse our cities in high-tech vehicles that remove us from any direct contact with the ground. Some of us regularly ride a bicycle but we rarely develop our balancing skills beyond our initial learning spurts. Entire cultures and infrastructures seem to be designed to shield us from encountering balancing challenges or disturbances. Even the yoga classes we attend – planting our bare feet on tidy studio floors and mats – rarely push us to explore our bodies’ ability to find balance in alternative, subtle ways. As Rosa notes in his remarkable book on resonance, despite their seeming innocuousness, even the shoes enfolding our feet “establish a highly effective ‘buffering’ distance between body and world that allows us to move from a participative to an objectifying, reifying relationship to the world”.

If the result of all this shielding is that we have weakened our ability to engage in balancing at the embodied level, how might we reclaim and strengthen that ability? We must reach for a sense of balance that is flexible and dynamic more than rigid and static, productive of a lively sense of security as well as relationality. The good news is that life offers abundant opportunities to experiment with diverse ways of balancing on the Earth if we choose to grasp them.

“The Universe is a limitless circle with a limitless radius. This condensed becomes the one point in the lower abdomen which is the center of the Universe”

Skateboarding, an early hobby growing up in Southern Finland, taught me some early lessons about the art of balance. First, learning to ride the streets on a wobbly board and mastering a range of jumps and pivots turned balancing into a playful, addictive challenge. Inevitably, I also quickly learned a second lesson: failing to balance could lead to tremendous pain. The feedback from losing one’s footing was immediate and merciless – there were no verbal excuses or buffers that could render impact with the pavement any less punishing. Yet for all these important learnings, I subsequently realized that not only did skateboarding ultimately keep me at a certain distance from the ground (through shoes, boards and asphaltic surfaces) but it also imposed limits on how I could connect with my own body.

By contrast, contemporary improvisational dance offers a form of playful movement that promotes a more nuanced and experimental connection with one’s body. It invites us to explore unfamiliar ways of moving ourselves upon the ground and through the air while responding fluidly to others around us. The neuroscientist and brain health champion Hanna Poikonen of ETH Zurich suggests that it is the way in which those engaged in improvisational dance listen to their internal signals that sets this form of dance apart. By becoming so attuned to their bodies, improv dancers allow embodied sensations to guide their next actions in the moment. This bodily intelligence invites one to explore diverse ways of balancing in an emergent fashion. Practitioners may choose to intentionally confront and experiment with various sources of stiffness, shakiness and difficulty in relation to balance. What emerges (along with improvements to one’s health) is a certain sense of comfort with feeling unbalanced, and from this the profound realization that as living and moving human beings, we are constantly engaged in balancing rather than “in balance”. Perfect balance is neither possible nor desirable, for it would fix us in place, like lifeless statues. Instead, the options available to us are not binary (being in balance vs losing one’s balance) but dynamic and infinite in character: it is always possible for us to discover new, lively ways of balancing.

Anatomical Flap Book (1667). Remmelin.

Japanese martial arts such as karate and aikido offer a more spiritually tuned approach to balance and movement. Sharing with improvisational dance a strict preference for encountering the ground, floor or tatami barefoot, traditional martial arts place central importance, both philosophically and practically, on a specific area roughly two inches below the bellybutton. Known as tanden or sometimes as hara, this special area inside the lower abdomen is considered key to accessing one’s highest powers through the unification of body, mind and spirit.

While Japanese martial arts and movement instructors often point out that tanden is located at or near the body’s centre of gravity in a physical sense, it is tanden’s role as a focal point or container for universal energy that is given far more primacy. In the words of the aikido master and Ki Society founder Tohei Koichi (1920-2011), “[t]he Universe is a limitless circle with a limitless radius. This condensed becomes the one point in the lower abdomen which is the center of the Universe”.²

In practice, it is through mindful breathing that outside energy is thought to enter the body, allowing the practitioner to feel that they exist as part of nature and its ongoing cycles, as observed by Nagatomo Shigenori in Attunement Through the Body (1992).

Remarkably, then, power and balance in martial arts are achieved not only through the efforts of the individual practitioner but through an embodied and flowing sense of connection with the natural world that envelopes them. Here, breath serves as the ongoing link between outer and inner energies, between the individual and the world..Balance is found when both come together through vital ki energy and when that energy is harmonized with movement.

So, it seems that balancing on the Earth is not quite as ordinary or narrow a process as we might have initially suspected. Once you begin to reconnect with your body and its ability to balance in subtly, or dramatically, different ways, potent insights start to emerge. We are never “in balance” but rather always balancing. That act of balancing – which we normally carry out unconsciously – can be made more intentional and vibrant. It can even offer paths to “embodied integration” with the living world and the universe, through the alignment of breath and movement. Through dance and other playful forms, it is entirely possible to become more comfortable with fluidity and lack of stability. Falling out of balance is not always a bad thing, even if it leads to temporary pain. Rather, it is the refusal to fully engage with our bodies, their incredible capacities for motion and the rich textures of the Earth that may leave us with a chronic sense of unsteadiness.

One secret to making our existence genuinely lively and resonant may be to redefine balancing as a conversation we can have with the Earth with our bodies. As with any dialogue that transcends conventional boundaries, binary distinctions and assumptions, it might prove as nurturing and transformative as the conversations you have with the people you most gravitate towards.

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.

¹ Rosa, Hartmut (2019). Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World. Polity Press, p. 38.

² Tohei, Koichi (2022). Ki Sayings. Ki Society HQ, p.5

Lapis Lazuli (Artefact IV)

Ben Timberlake August 6, 2024

The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural…

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 4

Description: Ultramarine from Lapis Lazuli

Location: Sare-e-Sang, Badakhshan, Afghanistan

Age: 6000BC to Present

Ben Timberlake August 6, 2024

Blue is the color of civilization. It is the color of heaven.

When the first prehistoric artists adorned the cave walls, they used the earth colors: reds, browns, yellows, blacks. There were no blues, for the earth very rarely produces the color. Early peoples had no word for blue: it doesn’t appear in ancient Chinese stories, Icelandic Sagas, the Koran, or Sumerian myths. In the Odyssey, an epic with no shortage of opportunities to use the word, there are plenty of blacks and whites, a dozen reds, and several greens. As for the sea - Homer describes it as “wine-dark”.

Philologist Lazarus Geiger analyzed a vast number of ancient texts and found that the words for colors show up in different languages in the same sequence: black and white, next red, then either yellow or green. Blue is always last, arriving with the first cities and the smelting of iron. Homer’s palette, at the end of the Bronze Age, sits neatly within this developmental scheme.

The Egyptians had a word for blue, for they also had the tools of civilization, long-distance trade, and technology, that allowed them to seek out and harness the color. 6000 years ago, the very first blue they used - the true blue - was ultramarine from Lapis Lazuli (the ‘Stone of Heaven’), found in the Sar-e-Sang mines in northern Afghanistan. It was this blue that adorned the mask of Tutankhamun, and that Cleopatra wore, powdered, as eye-shadow.

Lapis lazuli was so expensive that the Egyptians were driven to some of the earliest chemistry experiments - heating copper salts, sand and limestone - to create an ersatz turquoise that was the world’s first synthetic pigment. The technology and recipe spread throughout the ancient world. The Romans had many words for different varieties of blue and combined Egyptian Blue with indigo to use on their frescoes. But none of these chemical creations or combinations could match the Afghan lapis for the brilliance of its blues.

“The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural.” - Wassily Kandinsky

The Virgin in Prayer, Giovanni Battista Salvi da Saassoferrato, c.1645.

At the Council of Ephesus in 431AD, ultramarine received official blessing when it was decided that it was the color of Mary, to venerate her as the Queen of Heaven. Since then it has adorned her robes and that of the angels. Ultramarine was the rarest and most exotic color. Its name - meaning ‘beyond the sea’ - first appeared in the 14th century, given by Italian traders who brought it from across the Mediterranean. Lapis Blue was more expensive than gold and was reserved for only the finest pieces done by the most gifted artists.

It was the most expensive single cost in the whole of the Sistine Chapel and it is said that Michelangelo left his painting The Entombment unfinished in protest that his patron wouldn’t pay for ultramarine. Raphael reserved the color for the final coat, preferring to build the base layers of his blues from Azurite. Vermeer was a master of light but less good at economics: he spent so much on the ultramarine that he left his wife and 11 children in debt when he died.

Once again, mankind turned towards chemistry to search for a cheaper blue: in the early 1800s France’s Societé d’Encouragement offered a reward of 6000 Francs to a scientist who could create a synthetic ultramarine. The result was ‘French Ultramarine’ a hyper-rich color that is still with us to this day.

But 200 years later there is still a debate as to whether we have lost something. Alexander Theroux in his essays The Primary Colors wrote “Old-fashioned blue, which had a dash of yellow in it... now seems often incongruous against newer, staring, overly luminous eye killing shades”.

Anthropometry: Princess Helena, Yves Klein, 1960.

True ultramarine is perfect because of its flaws. It contains traces of calcite, pyrite, flecks of mica, that reflect and refract the light in a myriad of ways. Many artists have continued to prize it for its shifting hues, the heterogeneity of the brushstrokes it creates, the feelings it stirs in us. As Matisse said, ‘A certain blue penetrates the soul’.

Yves Klein worshiped the color and used the synthetic version but he owed his inspiration to the real thing. Klein was born in Nice and grew up under the azure blue Provencal skies. At the age of nineteen he lay on the beach with his friends - the artist Arman, and Claude Pascal, the composer - and they divided up their world: Arman chose earth, Pascal words, while Klein asked for the sky which he then signed with his fingers.

It was only when Klein later visited the Scrovegni Chapel and saw the ultramarine skies of Giotto’s paintings did he understand how to achieve his calling. Klein devoted his brief life to the color, he even patented International Klein Blue (IKB), a synthesis of his childhood skies and the stone of heaven itself.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

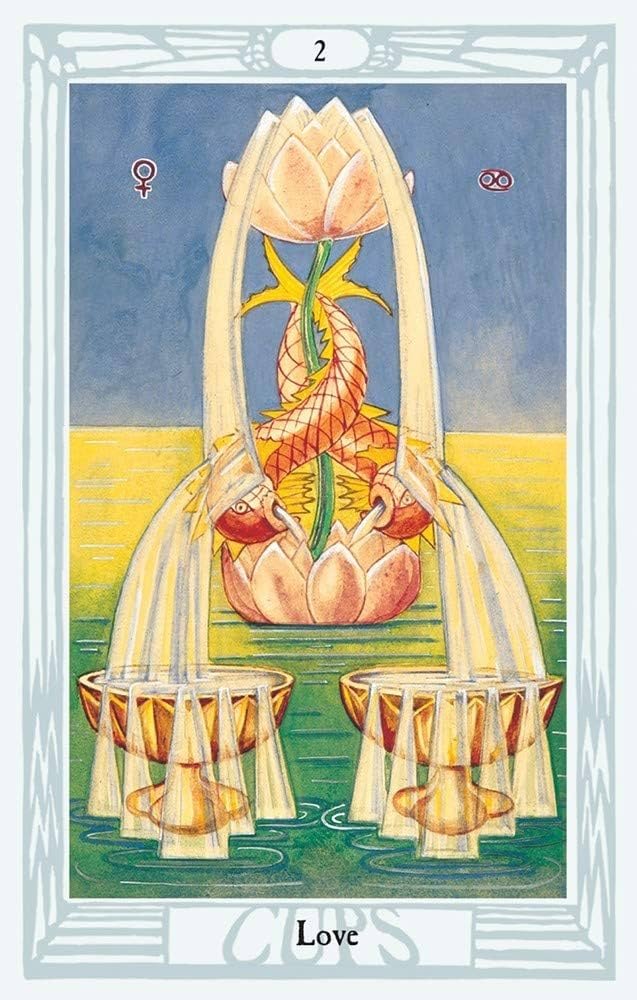

The Three of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 3, 2024

The Three of Cups is the card of emotional intimacy, and the act of pouring one's heart out. These are the emotional declarations that arise from a night of drinking as the heart overflows…

Name: Love, the Three of Cups

Number: 3

Astrology: Mercury in Cancer

Qabalah: Binah of He

Chris Gabriel August 3, 2024

The Three of Cups is the card of emotional intimacy, and the act of pouring one's heart out. These are the emotional declarations that arise from a night of drinking as the heart overflows.

In Rider, we see three women making a toast, their cups are raised high. Each has a flowing dress and flowing hair, and they seem to be dancing in an orchard. The sky is blue, and they are smiling.

In Thoth, we see three cups, where each seems to be formed like a cluster of grapes. Lotuses shower water into them, and they flow into one another. The cups are crimson, the lotuses yellow, and the ocean they sit upon is a deep blue. This card is Mercury in Cancer, thus the gold and blue.

In Marseille, we find the same structure as Thoth, one cup atop two, and flowers going between. Through Qabalah we find the phrase “The Understanding of the Queen”

The Understanding of the Queen is Abundance.

The astrological character of this card, Mercury in Cancer, or emotional communication is perfectly symbolized in Rider Waite, it is the card of “Girls Night”, when women get together to drink wine and talk. This is the great catharsis of relieving pressures that build up throughout life when we pour our hearts out into one another's cups and drink.

As this card belongs to the Queen, the idea of speaking one's heart tends to be seen as feminine. Though exemplified and illustrated as being the domain of women, it does not exclude male friendships and the drunken expressions of love that accompany it.

These are the emotions brought out by drink, whether regularly or rarely. The gender divide is essential to this being the Queen’s Understanding, as opposed to the King’s Understanding in the Three of Wands, which is daily virtue.

We should acknowledge that these gender divides and stereotypes are outdated and can be quite silly, but for the purposes of understanding the Tarot it is necessary to explore them.The Three of Wands, the masculine equivalent to this feminine card, is about the masculine drive for simplicity, as opposed to the feminine drive for abundance seen here. The Stoic King might take pride in sleeping on the floor, but the Queen knows a royal bed is more fitting.

Of course, this is not an abundance of stuff, but of emotion. Our feelings are a great store of value; they are not a hindrance or a flaw, but a brilliant source of connection to our deepest truth. This card shows that the Queen understands how to utilize this wealth of emotion through engagement.

The division of elements and genders is not essentially biological, but spiritual, anyone can experience all aspects of the tarot.

When pulling the Three of Cups we are asked to engage in emotional catharsis, to see the abundance we have before us, to let our hearts overflow. It can also signify a coming abundance, an event that will bring much emotion with it. Do not shy away from your heart, let it be abundant!

Numerology, Fibonacci, and Magic

Flora Knight August 1, 2024

Fibonacci sequences may not hold a prominent place in traditional magic or witchcraft, but to study them reveals the underlying principles that are deeply intertwined not just with sacred geometry and the natural spirals of the universe, but with the mystical world in it’s totality…

Albrecht Durer, Melencolia I featuring a magic numerology square. (1514)

Flora Knight August 1, 2024

Fibonacci sequences may not hold a prominent place in traditional magic or witchcraft, but their underlying principles are deeply intertwined with sacred geometry and the natural spirals of the universe. Two spiritual interpretations derived from the Fibonacci sequence are particularly noteworthy in our modern magical understandings, and particularly in the practice of Wicca: the concepts of twin flames and the number 33 sequence.

The spiral and golden rectangle of the Fibonacci sequence.

The idea of twin flames has long been embedded in magical traditions. Love, often symbolized by two flames, is a recurring theme in love spells and incantations, where lighting two candles side by side is believed to elevate love to a higher spiritual plane. This concept is represented by the number 11, a significant number in witchcraft. The Fibonacci sequence begins with 1 + 1, a numerical foundation that has been embraced by some modern Wicca sects as resonating with the essence of twin flames.

Another intriguing use of the Fibonacci sequence involves starting the sequence with the number 33. The number 3 represents the mind, body, and spirit, so 33 symbolizes the spiritual realization of these elements. When the Fibonacci sequence begins with 33, it leads to important numbers such as 3, 6, and 9, which are said to represent the ascension of the universe. Mapping these numbers on a grid also forms a pentagram, a powerful symbol in Wicca.

The 12th number in this modified Fibonacci sequence is 432, a number of profound significance in modern Wicca. The frequency of 432 Hz resonates with the universe’s golden mean, Phi, and harmonizes various aspects of existence including light, time, space, matter, gravity, magnetism, biology, DNA, and consciousness. When our atoms and DNA resonate with this natural spiral pattern, our connection to nature is enhanced.

The number 432 also appears in the ratios of the sun, Earth, and moon, as well as in the precession of the equinoxes, the Great Pyramid of Egypt, Stonehenge, and the Sri Yantra, among other sacred sites. While Fibonacci sequences were not commonly used in traditional magic before the 20th century, we see their presence everywhere, and they are meaningful in explanations of sacred geometry.

“This sequence, when viewed through a spiritual lens, reveals the underlying order and symmetry in nature, guiding us toward a deeper appreciation of the divine patterns that govern our existence.”

But beyond just Fibonacci, the study of numbers reveals secrets of the world, and to understand the magical perspective of the world, we must understand how different numbers carry various symbolic meanings:

William F. Warren, Illustration from Paradise Found. (1885).

1: The universe; the source of all.

2: The Goddess and God; perfect duality; balance.

3: The Triple Goddess; lunar phases; the physical, mental, and spiritual aspects of humanity.

4: The elements; spirits of the stones; winds; seasons.

5: The senses; the pentagram; the elements plus Akasha; a Goddess number.

7: The planets known to the ancients; the lunar phase; power; protection and magic.

8: The number of Sabbats; a number of the God.

9: A number of the Goddess.

11: The twin flames; the number of ethereal love.

13: The number of Esbats; a fortunate number.

15: A number of good fortune.

21: The number of Sabbats and Esbats in the Pagan year; a number of the Goddess.

28: A number of the Moon; a number 101 representing fertility.

The planets are numbered as follows in Wiccan numerology:

3: Saturn

7: Venus

4: Jupiter

8: Mercury

5: Mars

9: Moon

6: Sun

Numerology has been a significant aspect of witchcraft for nearly 3,000 years, with most numbers being assigned specific meanings by various magical traditions. The most consistent sacred numbers, linked to sacred geometry, are 4, 7, and 3. These numbers represent the universe, the earthly body, and the seven steps of ascension, respectively.

The story of the Tower of Babel illustrates the ancient understanding of the universe through numbers. The tower's seven stages were each dedicated to a planet, with colors symbolizing their attributes. This concept was further refined by Pythagoras, who is said to have learned the mystical significance of numbers during his travels to Babylon.