The Seven of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel October 5, 2024

The Seven of Wands is a card fighting against the odds. It symbolizes the willingness to fight a losing battle, and bravery in spite of terrible danger.

Name: Valour, the Seven of Wands

Number: 7

Astrology: Mars in Leo

Qabalah: Netzach of Yod

Chris Gabriel October 5, 2024

The Seven of Wands is a card fighting against the odds. It symbolizes the willingness to fight a losing battle, and bravery in spite of terrible danger.

In Rider, we find a young man in a green tunic battling off 6 wands wielded by unseen enemies beneath him. His face is angry. He has no support, but he goes on fighting.

In Thoth, we find 6 fine ritual wands crushed by a simple club. This is the base creative and violent energies that overcome what is structured and established, a battering ram that breaks in an ornate door. It is Mars in Leo, so there is a strong element of Pride, this is proving oneself against authority, or defending one's name from insult.

In Marseille, we have 6 wands crossed, and one beneath. Foliage sprouts from the sides. Qabalistically it is the Love of the King. The Love of the King is prideful and brave.

This card brings to mind many great battles, not least the Battle of Thermopylae where the 300 Spartans overcame a Persian army that numbered in the hundreds of thousands. A closer fit, however, is the Battle of Bunker Hill, where raggedy American militiamen held their own against the great British army. Though they lost, they proved their bravery was a match for superior training.

Perhaps the most direct example still, is the Battle of Stamford Bridge, marking the end of the Viking age. The key figure is an unknown Viking Berserker who makes a chokepoint on Stamford Bridge, single handedly holding off the English army. He kills 40 on his own, and is finally taken down by a soldier with a spear who struck him from under the bridge.

The Seven of Wands is past the point of Victory, the Six of Wands. This is not about fighting to win, this is fighting when all is lost.

Norman Rockwell, 1943. Oil on Canvas.

This is the card of Valour, of the lone soldier fighting an entire army. These countless historical events color the card well, but its ideas can be closer to home too. This is the card for when we hold our own opinion in spite of opposition. This is going against the grain, even when it’s uncomfortable.

The Norman Rockwell painting Freedom of Speech shows it well; a lone man standing up to voice his opposing opinion to the town. This is the willingness to engage in controversy, to dissent. Of course, this is not always positive. The subject of Rockwell’s painting is a man dissenting against the consensus to build a new school after it had burned down. The battles fought bravely for pride are often quite ridiculous.

When you pull this card, you may be faced with opposition, and you must face it bravely. Speak up, even when everyone else disagrees.

Life Is Right (1904)

Rainer Maria Rilke October 3, 2024

In 1902, while attending military college an hour outside of Vienna, Austria, the 19 year old Xavier Kappus began a correspondence with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, a respected and established writer who had, many years earlier, been tutored by the very same school master as Kappus himself. Seeking advice and criticism on his poetry, over 6 years and 10 letters, Rilke taught him something altogether more important...

Rainer Maria Rilke, October 3rd, 2024

In 1902, while attending military college an hour outside of Vienna, Austria, the 19 year old Xavier Kappus began a correspondence with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, a respected and established writer who had, many years earlier, been tutored by the very same school master as Kappus himself. Seeking advice and criticism on his poetry, over 6 years and 10 letters, Rilke taught him something altogether more important - a way to understand the world and navigate the difficulties of life with wonder, love, creativity, and hopefulness. The letters were collected into a book published as ‘Letters to a Young Poet’, which remains one of the most seminal and essential works of the 20th Century. The letter reproduced here was written in November of 1904, while Rilke was in Sweden.

My Dear Mr. Kappus,

In this time that has gone by without a letter I have been partly traveling, partly so busy that I could not write. And even today writing comes hard to me because I have already had to write a lot of letters so that my hand is tired. If I could dictate, I would say a great deal to you, but as it is, take only a few words for your long letter.

I think of you, dear Mr. Kappus, often and with such concentrated wishes that that really ought to help you somehow. Whether my letters can really be a help, I often doubt. Do not say: yes, they are. Just accept them and without much thanks, and let us await what comes.

There is perhaps no use my going into your particular points now; for what I could say about your tendency to doubt or about your inability to bring outer and inner life into unison, or about all the other things that worry you—: it is always what I have already said: always the wish that you may find patience enough in yourself to endure, and simplicity enough to believe; that you may acquire more and more confidence in that which is difficult, and in your solitude among others. And for the rest, let life happen to you. Believe me: life is right, in any case.

And about emotions: all emotions are pure which gather you and lift you up; that emotion is impure which seizes only one side of your being and so distorts you. Everything that you can think in the face of your childhood, is right. Everything that makes more of you than you have heretofore been in your best hours, is right. Every heightening is good if it is in your whole blood, if it is not intoxication, not turbidity, but joy which one can see clear to the bottom. Do you understand what I mean?

And your doubt may become a good quality if you train it. It must become knowing, it must become critical. Ask it, whenever it wants to spoil something for you, why something is ugly, demand proofs from it, test it, and you vail find it perplexed and embarrassed perhaps, or perhaps rebellious. But don’t give in, insist on arguments and act this way, watchful and consistent, every single time, and the day will arrive when from a destroyer it will become one of your best workers— perhaps the cleverest of all that are building at your life.

That is all, dear Mr. Kappus, that I am able to tell you today. But I am sending you at the same time the reprint of a little poetical work * that has now appeared in the Prague periodical Deutsche Arbeit. There I speak to you further of life and of death and of how both are great and splendid.

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) was an Austrian poet and novelist whose lyricism and literary intensity expanded the possibilities of the German language.

Disturbed Images

Lamia Priestley September 1, 2024

A roll of belly fat melts into a makeup-caked face; a bag of chips morphs into a family portrait; a butt cheek transforms into a policeman’s bicep. Gross and sickly, loud and pink, Frank Manzano’s collection of video works, Current Value (2023), uses AI imagery to depict the grotesque in everyday scenes of American suburban life—fistfights, plastic surgery, arrests.

Lamia Priestley October 1, 2024

A roll of belly fat melts into a makeup-caked face; a bag of chips morphs into a family portrait; a butt cheek transforms into a policeman’s bicep. Gross and sickly, loud and pink, Frank Manzano’s collection of video works, Current Value (2023), uses AI imagery to depict the grotesque in everyday scenes of American suburban life—fistfights, plastic surgery, arrests.

Still from Holistic Consumption Challenge (Current Value), Frank Manzano. (2023).

Rapid cuts between faces result in pile ups of interchangeable characters. An endless treadmill of trash, plastic consumer products, and open mouths, the videos’ choppiness creates what the Chicago-based artist describes as “the human parade”—a crazed illustration of people as stuff. Manzano describes his work as an exploration of “consumerism, massification, the loss of the self.” These themes are felt not just in the works’ subject matter but in the evidence of the mass market AI tools Manzano uses to make many of his images.

Manzano has a fondness for corpulent characters, big butts, cellulite, stretched thighs and teethy smiles. Outside of his focus on flesh, the videos themselves exert a materiality in their reference to the aesthetics of consumer visual culture and their artefacts. There’s the digital lines of security footage, the jacked up saturation of reality TV, the studio lighting of an 80s sitcom, the low res crunchy feel of camcorder home videos. The images look either consumer-grade (camcorder) or like something used to capture consumers (CCTV). But amongst the visual styles referenced in Manzano’s work, one can distinguish something entirely new, the artefacts of AI images.

To create this pastiche, Manzano uses a combination of his own photos, sourced images and ones he generates with AI image tools like Wombo. On a visual level, the artefacts of AI images—the airbrushed smooth skin, confused edges between fingers, gibberish logos and half-baked eyes—contribute to a feeling of the uncanny in these illustrations of the American underbelly. More than just a formal contribution though, these artefacts place the images into a context. Viewers who, over the past few years, have developed a familiarity with AI generated images online, will recognise them here and have some understanding of the process by which they are created—using a dataset of preexisting images. It’s clear that although Current Value’s images have the trademarks of documentary or recorded reality, many of them aren’t real.

“There’s something profane in the limitation of a finite dataset. The images have no hope of transcendence.”

The disturbing nature of Manzano’s videos is due, not to this irreality, but rather to the images’ self-aware embrace of their artificial generation. The AI artefacts are significant because of what they mean in the context of Manzano’s unaspiring video world. Not only are his subjects debased but so too are the images—a perfect marriage of subject and form.

Origins of Fetishization (Current Value), Frank Manzano. 2023.

The philosopher Hannes Bajohr offers a useful framework for understanding this earthbound quality of AI images in his article Algorithmic Empathy: Toward a Critique of Aesthetic AI (2022). Bajohr advocates for interpreting AI arts on their own terms, looking at how they’re made—their “technical substrate”—to develop their aesthetic critiques. Bajohr draws a parallel between artificial neural networks and the ancient aesthetic principle of mimesis—the attempt to imitate or reproduce reality in the creation of art. He outlines two opposing concepts of imitation as it relates to AI images. The first he attributes to the philosopher Hans Blumenberg’s explanation. It describes imitation as construction, which sees “the approximation of an existing state through the inference of the rules that bring it about.” The second concept of imitation, which better describes AI image making, is “imitatio naturae” (imitation of nature). A classical idea that was repopularised in the Renaissance, “imitatio naturae” sees imitation as a mere repetition of the real without the “procedural insight” of imitation as construction. In the case of AI image making, “nature” would be the dataset, and so that from which all representations are derived.

This first approach to imitation, that of construction, implies the possibility of depicting something new. Bajohr emphasises that with the knowledge of a thing’s creation—of its building blocks—moving beyond that thing is possible while in “imitatio naturae”, the representation derives directly from the thing itself. Nature, and so the dataset, is the absolute resource. An artificial neural network can’t truly imagine anything beyond its own dataset, never something outside of that which has already been represented.

There’s something profane in the limitation of a finite dataset. The images have no hope of transcendence. Image generators are so far unable to replicate the mysterious process by which a great artist goes about transforming an ordinary landscape into an image that might produce ineffable revelations in its viewers. The artist—studying how light falls, the relationships of colours, the phenomenon of perspective—might inexplicably assemble a few strokes of paint to reveal something much greater than valleys, woods, hills and streams, much greater than nature.

Manzano’s images are trapped. His subjects lead unambitious lives, marginalised by a cycle of consumerism, greed, lust, violence, and vanity; they're governed by their instincts, unable to escape themselves. So too, AI images exist only in immanence. Image generators simulate master artists’ styles from the past, merely recycling them, destined to make unambitious copies.

Current Value’s images are provocations. They’re affective, disturbing representations of the gutters of material culture because they themselves belong there, unable to dream themselves out.

Lamia Priestley is an art historian, writer and researcher working at the intersection of art, fashion and technology. With a background in Italian Renaissance Art, Lamia is currently the Artist Liaison at the digital fashion house DRAUP, where she works with artists to produce generative digital collections.

The Nine of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 28, 2024

The Nine of Wands is a card of perseverance through darkness. It represents the indomitable will of the lone survivor, who has the strength necessary to make it through to the end...

Name: Strength, the Nine of Wands

Number: 9

Astrology: Moon in Sagittarius

Qabalah: Yesod of Yod

Chris Gabriel September 28, 2024

The Nine of Wands is a card of perseverance through darkness. It represents the indomitable will of the lone survivor, who has the strength necessary to make it through to the end.

In Rider, we find a bandaged and raggedy man, standing with the help of one of the nine wands. Yet he is standing. This is a survivor who bears the marks of his struggle. Around him are 8 wands stuck in the ground. While the rest have gone or died, he remains.

In Thoth, we find the 9 wands as arrows. 8 Lunar arrows coming down. The central wand is connecting the Moon below to the Sun above. In many ways this is the most ritualistically significant card in the Thoth deck. It symbolizes the ritual of the Great Work of Thelema, that of Samekh. The movement past the Psyche and toward the Dæmon or Genius. This is the Mysterium Conjunctionis of the Alchemists, the marriage of the Sun and Moon.

In Marseille, we find a similar arrangement to Thoth, as 8 wands cross one another and a central wand is beneath them. Through Qabalah we find the name of this card to be “The Foundation of the King”. The Foundation of the King is Strength.

In some ways this is a dark card, concerned with immense struggle and difficulty, but here Nietzsche’s wisdom of “what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger” is affirmed. This is the path necessary for greatness.

This card makes me think of Apollo 11 and the “Moonshot”, mankind making the terrible and difficult journey through space to reach the Moon and the achievement of the impossible.

It also calls to mind the Star Spangled Banner:

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O'er the ramparts we watch'd, were so gallantly streaming?

And the Rockets' red glare, the Bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our Flag was still there;

The flag still standing amidst the chaos of war.

This is Nietzsche’s will to power that has brought man through the darkness of time. Even more, it is the will to dream and to achieve what is beyond - it is the best in us. Nietzsche even symbolized it with archery; in Zarathustra he feared this tendency could cease: Alas! there cometh the time when man will no longer launch the arrow of his longing beyond man—and the string of his bow will have unlearned to whizz!

The Nine of Wands is the arrow of our longing, the rocket to the moon, and the golden thread in the Labyrinth. It is what keeps us going.

When we pull this card, we may be faced with struggle and difficulty, but we must and will come out of it stronger. We may also be inspired with a great goal, a dream that we must achieve. It may be that this great dream helps us through the darkness.

On the Grasshopper

Ale Nodarse September 26, 2024

In November of 2017 a grasshopper was found lodged within the depths of Vincent van Gogh’s 1889 Olive Trees. Conservators celebrated the quiet revelation. Such an insect, they suspected, might finally divulge the season of the painting’s completion, the month — within that most productive, and final, year of van Gogh’s life — in which turbulent oil had come to rest. Further searching through pigment ensued. Tracing the most minute of ripples, as if to follow the insect’s final movements, proved futile. No such eddies emerged. The grasshopper, they concluded, died before it had been sealed in its oily envelope...

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, 1889. Oil on canvas, Nelson Atkins Museum, Kansas City.

Ale Nodarse, September 26, 2024

“And the almond tree shall flourish, and the grasshopper shall be a burden.” — Vincent van Gogh¹

“Terror and a beauty insoluble are a ribband of blue woven into the fringes of things both great and small.” — Annie Dillard²

In November of 2017 a grasshopper was found lodged within the depths of Vincent van Gogh’s 1889 Olive Trees.³ Conservators celebrated the quiet revelation. Such an insect, they suspected, might finally divulge the season of the painting’s completion, the month — within that most productive, and final, year of van Gogh’s life — in which turbulent oil had come to rest. Further searching through pigment ensued. Tracing the most minute of ripples, as if to follow the insect’s final movements, proved futile. No such eddies emerged. The grasshopper, they concluded, died before it had been sealed in its oily envelope.

The plein-air painter knew intimately the grasshopper (or sprinkhaan, in the artist’s native Dutch) and its kin. He complained of the travails of painting “on the spot itself” in a letter to his brother Theo, four years before Olive Trees was painted (July 14, 1885):

“I must have picked a good hundred flies and more off the 4 canvases that you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand etc. — not to mention that, when one carries them across the heath and through hedgerows for a few hours, the odd branch or two scrapes across them &c. Not to mention that when one arrives on the heath after a couple of hours’ walk in this weather, one is tired and hot. Not to mention that the figures don’t stand still like professional models, and the effects that one wants to capture change as the day wears on.”

The grasshopper of the Olive Trees, one suspects, arrived in such a bout of flies, or with a wind of dust and sand, or perhaps by a branch depositing the insect’s carcass upon wet canvas. In any case, the painter’s not to mentions, his niet meegerekend — or, more accurately, his “not counted (any)mores” — disclose, like the grasshopper, unanticipated revelations. For after a concession to his reader he does indeed count: a good hundred, 4, a few, or two, a couple.

Van Gogh rendered the canvas a thing which absorbs. Flies (living, or like the grasshopper, already dead) are drawn to it; dust and sand (and the innumerable particulates residing in his “etc.”) cling to it; branches scrape it. Its centimeters of oil testify still to each of these touches, depositions and engravings. But between the first and second not to mentions a change occurs. The painter describes himself absorbed, as if within a landscape that will, regardless of resistance, enumerate: that is, bring itself to his attention and to his counting. He, like his painting, transgresses dimensions. In oil as on ground, he moves not only “across the heath” but “through the hedgerows” (door de hei in Dutch). While recent exhibitions have cast Van Gogh’s images as flat, albeit immense, projections, to speak of the artist’s paintings is inevitably to speak of this movement through and to trace the former carrying — the dragging resistance — of his own body and brush.

“The ground that was painted and the ground that was tilled became increasingly one and the same.”

In the third not to mention the artist turns to his body — tired and hot — before moving a final time to the bodies of others. “The figures don’t stand still.” His complaint formed a critique of those who, like the painter Gustave Courbet, predicated their realism upon a return to the studio. (Of the figures within Courbet’s 1849 Stone Breakers, a work perennially invoked as foundational to the Realist movement, the painter wrote nonchalantly: “I made an appointment with them at my studio for the next day.”)⁴ Whereas Courbet conceived of the figure — of the peasant — as a transferable image disposed to the economics of the studio, Van Gogh insisted on his own absorption within the life of another. “The more I work on it,” he continues in the same to Theo, “the more peasant life absorbs me (me absorbeert).”⁴

Vincent Van Gogh, Women Picking Olives, 1889. Oil on Canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Through his work, the ground that was painted and the ground that was tilled became increasingly one and the same. The elements which Van Gogh would characterize as not mentionable –– flies, dust, and detritus –– would become, if at first paradoxically, proof. Proof of being there. They mark him and his canvases as they mark the laboring bodies to which he bore witness (which included women at work amidst those very trees.) The not mentionables insist on paintings not just as images but as objects. They make a proposition, too: that beauty lies in the counting and in the keeping hold of fragments which, however small, remain singular. Beauty, of such a kind, insists on the insolubility of seemingly dissolved parts; on the ribbon which may be picked out, to draw from Dillard’s analogy, from the greater weave. Beauty is an insistence on presence.

The painter, and his canvas, hold space for the ‘not to mention’ to be mentioned still. And since questions of recognition become questions of ethics, its insistence ought to weigh on us. What would it mean, the painting asks, to consider the grasshopper? What would it mean to be burdened by that which appears — all but — gone?

¹Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh (Amsterdam, September 18, 1877. No. 131). The letter was composed after van Gogh attended Rev. Jeremie Meijjes’s Sermon on Ecclesiastes XI:7–XII:7. For the original and translated letters, see vangoghletters.org.

²Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (Harper’s Magazine Press, 1974), 24.

³ “Grasshopper Found Embedded in van Gogh Masterpiece,” on the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art’s site. Link: https://nelson-atkins.org/grasshopper-found-embedded-van-gogh-masterpiece/.

⁴ Gustave Courbet, Letter to Francis Wey (November 26, 1849), translated in Marilyn Stokstad and Michael Cothren, Art History (Boston: Prentice Hall, 2011), 972. See Linda Nochlin, Realism: Style and Civilization (Baltimore: Penguin, 1971), 120–1; and, T. J. Clark, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 79–81.

⁵ Van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh (Neunen, on or about Tuesday, July 14, 1885. No. 515.).

Alejandro (Ale) Nodarse Jammal is an artist and art historian. They are a Ph.D. Candidate in History of Art & Architecture at Harvard University and are completing an MFA at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art. They think often about art — its history and its practice — in relationship to observation, memory, language, and ethics.

Head, The Monkees and the Search of Authenticity

Ana Roberts September 24, 2024

In 1968, Micky Dolenz jumped off the Gerald Desmond Bridge. Some eighty minutes later, he did it again, this time joined by the rest of The Monkees—Peter Tork, Davy Jones, and Michael Nesmith. Head, the 1968 film penned by Jack Nicholson and starring The Monkees, was the vehicle for this bridge jump—a filmic suicide that served equally as a career one...

Micky Dolenz falls from the Gerald Desmond Bridge, Head (1968).

Ana Roberts, September 24th, 2024

In 1968, Micky Dolenz jumped off the Gerald Desmond Bridge. Some eighty minutes later, he did it again, this time joined by the rest of The Monkees—Peter Tork, Davy Jones, and Michael Nesmith. Head, the 1968 film penned by Jack Nicholson and starring The Monkees, was the vehicle for this bridge jump—a filmic suicide that served equally as a career one. Not that there was much life left in The Monkees by 1968; the final episode of their show had aired in March, and their latest album, The Birds, the Bees & the Monkees, had failed to top the charts in America and didn’t even break the top ten in the UK—their first to miss both marks.

The Vietnam War, the assassinations of both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, riots in Chicago, and Soviet pressures across Eastern Europe all contributed to a waning optimism, within which there was hardly a place for the naïve antics of the Prefab Four. Yet Head is far from naïve. It is a psychedelic experiment—intentionally mind-numbing and academically stimulating—serving as a fourth-wall-breaking political critique of everything from the American collegiate sports system to dandruff commercials, with war, media, and reality thrown in for good measure. The film flopped spectacularly. It made just $16,000 from its $750,000 budget and was derided by Monkees fans, hippies, academics, and critics alike. It was too conceptual for the core fan base, mostly teen girls, and too Monkees for anyone else the film was aiming for.

Yet Head has prevailed. In the years following its release, it built a cult following and achieved a niche but significant level of critical success, regarded as a cornerstone object of the era that encompasses the themes, politics, and feelings of the late '60s. It was entered into the Criterion Collection in 2010 and hailed by Criterion critic Chuck Stephens as “arguably the most authentically psychedelic film made in 1960s Hollywood.” Stephens is right—Head is a staggeringly authentic film in so many ways. Much of the joy of watching it lies in seeing The Monkees, unable to play anything but their teeny-bopper TV show selves, juxtaposed with legitimate, psychedelic social criticism. It is within this brilliant contradiction that the question arises: How did the era’s least authentic band create its most authentic film? And why was it so readily rejected and ignored as a false work, with no authentic merits, by the contemporary counterculture—among whom authenticity was a primary obsession?

“They were inside the wrong thing and outside the right one. This strange combination, teamed with the genuine rebelliousness and otherness of Jack Nicholson, uniquely positioned them to make the most astute criticism of their time.”

There are simple answers to these questions if we want them. Nesmith’s affinity for Nicholson and the hippie scene, paired with a studio believing that combining a cultural zeitgeist with a teen phenomenon would be financially viable, accounts for the creation of the film. Sgt. Pepper’s had been released to critical and commercial success the year before, proving that boy bands could be both psychedelic and successful. This explains much of the film’s genesis. As for the rejection of Head by the counterculture, it feels wholly logical—the only quality the counterculture valued more than authenticity was “cool,” and The Monkees, for all their possible genius, were achingly uncool. Yet these answers do not hit at the crux of the issue: that of authenticity.

Authenticity was not a problem solely for The Monkees; it was a primary concern for almost every post-war artist who tried to shape a public image that wasn’t always in line with their true selves. Regardless of where they started, most were to some extent manufactured by a team around them. The Monkees are discussed in terms of authenticity not because they were the first or only inauthentic band of the era—arguably, they were neither—but because they were among the rare few who acknowledged their own inauthenticity. Later, with Head, they acknowledged their own attempt toward authenticity.

Frank Zappa and Davy Jones in Head (1968).

At its heart, Head is a film about freedom, and the failed attempt to achieve it in a world that wants not just The Monkees, but all public figures, to be a shiny, televised version of themselves, sanitized even in their rebellion. After the opening suicide, each of the four band members kisses the same groupie and is told that they are indistinguishable from one another. They race through various genres and films, moving in unrelated vignettes as if they were aliens dropped randomly across a film studio lot. They fight in the trenches of war, ride horseback across the great American West, and solve a murder mystery in ominous, decadent housing. In each scenario, they try to prove that they are four real, individual people in a real band that makes real music that real people listen to. Yet, at every turn, they find that this pursuit is meaningless—everything they are doing is sanctioned, fated, directed, and written by the producers of the film they are trying to escape. They break the fourth wall repeatedly, intentionally flubbing lines, acknowledging actors, and referencing the flimsy walls of the set they are on—only to find that this, too, is in the script that Jack Nicholson, appearing as himself and playing his actual role as producer, wrote for them. From start to finish, it is a wild ride—a kind of Ouroboros that eats itself in its meta-reflective analysis. It digs through philosophical ideas again and again, only to find that it has dug so deep it returns on the other side, no closer to the surface than when it began—with a synthetic boy band playing their hits to an audience who don’t truly know them, and would rather keep it that way.

The film was released at the tail end of the capital-S "Sixties," before the killing at the Rolling Stones concert in Altamont turned the whole decade into a bad trip. Despite the turmoil in the world, there was still a tie-dyed, tune-in, drop-out, mind-expanding, world-changing hopefulness that believed art, youth, truth, and rebellion could really change the world. The Monkees, for most of their career, had been a distillation of this attitude—neatly packaged by executives to be sold for syndication on TV channels across the world and played relentlessly on every wavelength. They were able to operate as both insiders and outsiders, feeling less shame about their participation in the system that everyone else was pretending not to be part of. They were inside the wrong thing and outside the right one. This strange combination, teamed with the genuine rebelliousness and otherness of Jack Nicholson, uniquely positioned them to make the most astute criticism of their time. That this critique is seen to come from the most unlikely place is, perhaps, incorrect—they were the only ones who could do it so explicitly.

Head is bombastic and exaggerated, but it cuts through to something that everyone else was too scared to be honest about. The Beatles danced around the ideas on Glass Onion, Dylan nodded to them with Ballad of a Thin Man, and even Elvis, in his countless motion pictures, tried to comment on them. But all cared too much about their artistry to acknowledge that they were participating in a system they claimed to be outside of. It took The Monkees, the least cool of all, to truly speak truth to power, and they paid the price for it. In the closing minutes of the film, as the final Monkee falls to his watery death, the director wheels their soaked bodies away in a large aquarium, the band struggling as they awake, and stores it neatly on a studio lot—to be used again whenever deemed fit.

Ana Roberts is a writer, musician and culture critic.

The Hierophant (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 21, 2024

The Hierophant is the materialization of divine wisdom and power. He is the embodiment of spiritual authority. He speaks for God and gives out his edicts to the bishops, and they spread it down the hierarchy.

Name: Hierophant or Pope

Number: V

Astrology: Taurus

Qabalah: Vau

Chris Gabriel September 21, 2024

The Hierophant is the materialization of divine wisdom and power. He is the embodiment of spiritual authority. He speaks for God and gives out his edicts to the bishops, and they spread it down the hierarchy.

In Rider, we find a young pope with a false beard sitting on a throne. He is adorned in scarlet. One hand raises a staff, his papal ferula, while the other is held aloft with two fingers to God. He has an ornate papal tiara. Beside him are two pillars, and beneath him are two tonsured clergymen and the Keys of Heaven.

In Thoth, we have a statuesque Hierophant. His bearded face is a mask and he is adorned in orange. One hand raises a Borromean staff, the other points down with two fingers. He wears a simple mitre on his head and on his chest,a star with the Aeonic Child inside. Beside him are two elephants and a bull, Taurean symbols. Before him is the “woman girt with a sword” as described in Liber Al, The Book of the Law. All around him are the four elemental Cherubs, and above is a five petaled flower encircled by a serpent and 9 nails.

In Marseille, we have an old pope sitting on his throne in a scarlet cloak. Both his bare and gloved hands are marked by crosses. His gloved hand raises the papal ferula, while the other raises two fingers to God. Beneath him are two tonsured clergymen.

The Hierophant or Pope is the head of the Church. He metes out orders from God and rules through hierarchy. For each church under his rule, he ensures that they function and share his dogma.

As Taurus, this is a card concerning stubborn commitment to the set way. It is also about simplicity and comfort. In this way, fast food, soda, and comfort foods are similar to the Church. Warhol describes it well: “A coke is a coke and no amount of money can get you a better coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the cokes are the same and all the cokes are good.” This is the Hierophant, he creates a spiritual doctrine made available to all.

The Hierophant makes that possible through a set of clear methods. He oversees the structured, accessible, universal path to God. His wisdom is standardized, not ephemeral. The Magician and High Priestess are spiritual forces as well, but they don’t follow dogmas in the same way; they have direct, personal routes to the divine. The Church and the Pope, on the other hand, have a grand and strict purpose.

Through the Hierophant, we are given the invitation and rules to the tarot. The old doctrines hold the truths tighter than we’re used to. What Thoth shows freely is hidden deep within Rider and Marseille. The Hierophant is in no rush to save the world, he is comfortable patiently and diligently following the divine rules set millennia before.

When you pull the Hierophant it may be that you must utilize your knowledge, or gain help from someone wise. This can be practical knowledge and spiritual knowledge.

The Postmodern Condition

Jean-Francois Lyotard September 19, 2024

Science has always been in conflict with narratives. Judged by the yardstick of science, the majority of them prove to be fables. But to the extent that science does not restrict itself to stating useful regularities and seeks the truth, it is obliged to legitimate the rules of its own game. It then produces a discourse of legitimation with respect to its own status, a discourse called philosophy…

Roy Litchenstein, Sunrise. 1963.

Jean-Francois Lyotard, September 19th, 2024

Commissioned by the government of Quebec, Lyotard undertook a philosophical study on the affects of modern life and capitalist culture on the metaphysical health of the world. He finds an inivetability to a lack of consensus and sees differences and conflict as inherent in the modern world, yet he remains positive that postmodernism retains the modernists ideals of maintaining the hope for a new kind of social existence.

Science has always been in conflict with narratives. Judged by the yardstick of science, the majority of them prove to be fables. But to the extent that science does not restrict itself to stating useful regularities and seeks the truth, it is obliged to legitimate the rules of its own game. It then produces a discourse of legitimation with respect to its own status, a discourse called philosophy. I will use the term modern to designate any science that legitimates itself with reference to a metadiscourse of this kind making an explicit appeal to some grand narrative, such as the dialectics of Spirit, the hermeneutics of meaning, the emancipation of the rational or working subject, or the creation of wealth. For example, the rule of consensus between the sender and addressee of a statement with truth-value is deemed acceptable if it is cast in terms of a possible unanimity between rational minds: this is the Enlightenment narrative, in which the hero of knowledge works toward a good ethico-political end - universal peace. As can be seen from this example, if a metanarrative implying a philosophy of history is used to legitimate knowledge, questions are raised concerning the validity of the institutions governing the social bond: these must be legitimated as well. Thus justice is consigned to the grand narrative in the same way as truth.

Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives. This incredulity is undoubtedly a product of progress in the sciences: but that progress in turn presupposes it. To the obsolescence of the metanarrative apparatus of legitimation corresponds, most notably, the crisis of metaphysical philosophy and of the university institution which in the past relied on it. The narrative function is losing its functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal. It is being dispersed in clouds of narrative language elements - narrative, but also denotative, prescriptive, descriptive, and so on. Conveyed within each cloud are pragmatic valencies specific to its kind. Each of us lives at the intersection of many of these. However, we do not necessarily establish stable language combinations, and the properties of the ones we do establish are not necessarily communicable.

Thus the society of the future falls less within the province of a Newtonian anthropology (such as stucturalism or systems theory) than a pragmatics of language particles. There are many different language games - a heterogeneity of elements. They only give rise to institutions in patches - local determinism.

The decision makers, however, attempt to manage these clouds of sociality according to input/output matrices, following a logic which implies that their elements are commensurable and that the whole is determinable. They allocate our lives for the growth of power. In matters of social justice and of scientific truth alike, the legitimation of that power is based on its optimizing the system's performance - efficiency. The application of this criterion to all of our games necessarily entails a certain level of terror, whether soft or hard: be operational (that is, commensurable) or disappear.

The logic of maximum performance is no doubt inconsistent in many ways, particularly with respect to contradiction in the socio-economic field: it demands both less work (to lower production costs) and more (to lessen the social burden of the idle population). But our incredulity is now such that we no longer expect salvation to rise from these inconsistencies, as Marx did.

Still, the postmodern condition is as much a stranger to disenchantment as it is to the blind positivity of delegitimation. Where, after the metanarratives, can legitimacy reside? The operativity criterion is technological; it has no relevance for judging what is true or just. Is legitimacy to be found in consensus obtained through discussion, as Jurgen Habermas thinks? Such consensus does violence to the heterogeneity of language games. And invention is always born of dissension. Postmodern knowledge is not simply a tool of the authorities; it refines our sensitivity to differences and reinforces our ability to tolerate the incommensurable. Its principle is not the expert's homology, but the inventor's paralogy.

Here is the question: is a legitimation of the social bond, a just society, feasible in terms of a paradox analogous to that of scientific activity? What would such a paradox be?

Jean-Francois Lyotard (1924 –1998) was a philosopher, sociologists and literary theorist.

The New Painting

Guillaume Apollinaire September 17, 2024

The new painters have been sharply criticized for their preoccupation with geometry. And yet, geometric figures are the essence of draftsmanship. Geometry, the science that deals with space, its measurement and relationships, has always been the most basic rule of painting.

Jost Amman, Wenzel Jamnitzer. 16th Century.

Guillaume Apollinaire, September 17th, 2024

Guillaume Apollinaire was a poet, playwright, novelist, and art critic who inspired and was admired by the Cubists and Surrealists, movements that he himself coined the terms for. Here, he writes in strong defence of Cubism against the public disdain, and shows how despite the modernity of their style, they are applying ancient laws and ideas that grounds them in tradition. He draws a comparison between Euclidian Geometry and Cubism first in a series of lectures in 1911 and then put them into words here, in 1912.

The new painters have been sharply criticized for their preoccupation with geometry. And yet, geometric figures are the essence of draftsmanship. Geometry, the science that deals with space, its measurement and relationships, has always been the most basic rule of painting.

Until now, the three dimensions of Euclidean geometry sufficed to still the anxiety provoked in the souls of great artists by a sense of the infinite – anxiety that cannot be called scientific, since art and science are two separate domains.

The new painters do not intend to become geometricians, any more than their predecessors did. But it may be said that geometry is to the plastic arts what grammar is to the art of writing. Now today's scientists have gone beyond the three dimensions of Euclidean geometry. Painters have, therefore, very naturally been led to a preoccupation with those new dimensions of space that are collectively designated, in the language of modern studios, by the term fourth dimension.

Without entering into mathematical explanations pertaining to another field, and confining myself to plastic representation as I see it, I would say that in the plastic arts the fourth dimension is generated by the three known dimensions: it represents the immensity of space eternalized in all directions at a given moment. It is space itself, or the dimension of infinity; it is what gives objects plasticity. It gives them their just proportion in a given work, where as in Greek art, for example, a kind of mechanical rhythm is constantly destroying proportion.

Greek art had a purely human conception of beauty. It took man as the measure of perfection. The art of the new painters takes the infinite universe as its ideal, and it is to the fourth dimension alone that we owe this new measure of perfection that allows the artist to give objects the proportions appropriate to the degree of plasticity he wishes them to attain.

Wishing to attain the proportions of the ideal and not limiting themselves to humanity, the young painters offer us works that are more cerebral than sensual. They are moving further and further away from the old art of optical illusion and literal proportions, in order to express the grandeur of metaphysical forms.

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) was a poet, playwright, novelist and art critic.

Ten of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 14, 2024

The Ten of Wands is the bitter end of Fire’s descent from Heaven. It has fallen from the spiritual heights it thrives in down to the material world. This is a card of weight, labor, and responsibilities that crush the spirit…

Name: Oppression, the Ten of Wands

Number: 10

Astrology: Saturn in Sagittarius

Qabalah: Malkuth of Yod

Chris Gabriel September 14, 2024

The Ten of Wands is the bitter end of Fire’s descent from Heaven. It has fallen from the spiritual heights it thrives in down to the material world. This is a card of weight, labor, and responsibilities that crush the spirit.

In Rider, we find a man bearing ten large wands, he is bending under the weight of his heavy load. In the distance we see a town, his destination still far off.

In Thoth, two leaden wands crush the eight light blue wands beneath them. It is oppression, Saturn in Sagittarius. As with the Five of Wands, Saturn is smothering the freedom of the fire which is escaping out the sides. This is especially pronounced here, as Sagittarius demands freedom of movement. The two lead wands are modified Eastern Phurbas, ritual dagger-staffs.

In Marseille, we find a similar configuration to Thoth, though the two vertical wands are beneath the crosshatched eight. Flowers are sprouting from the sides, life from the deadened, crystallized fires. As a ten, this card symbolizes Malkuth, the Kingdom, and being Wands, it belongs to the King. Thus it is the King’s Kingdom.

This card is the material reality of hierarchical power where the lofty philosophies and justifications behind oppressive regimes and states rest on the oppression of their people. While the Five of Wands showed us a tyrannical king causing strife in his court, this card is the oppressed peasantry who live under them.

The image that arises is that of the Fasci, a bundle of sticks that are weak on their own but strong together. An ancient Roman symbol taken up by many governments throughout history, but most significantly by Mussolini and his Fascist government. The ideal of strength through unity is one thing, but the question of who is to carry that heavy bundle is another. Saturn is the oppressive state, and Sagittarius is the people. They are anathema. Sagittarius needs to move freely, and Saturn needs to restrict and stabilize to maintain its power. Revolt is inevitable.

Materially, we can see this as a fire being smothered, whether this is at the onset when one adds too much wood to a tiny fire and chokes it of oxygen, or when a fire is raging and one covers it to kill it.

This is certainly not a comfortable card. When it comes up in a reading it can indicate serious pressures, smothering responsibilities, and exhaustion. This is a card of labor, hard work. Rider shows that the destination is in view, that the toils have a clear end, but there is no such promise in Marseille and Thoth, the oppression is simply there, dull and stupid work that must be done.

We can counter this by keeping the inner fire burning and finding outlets where it can run free.

Rediscovering Living Time

Tuukka Toivonen September 12, 2024

Amid our species' many disagreements, the steady progression of time seems to be the one thing that everyone can agree upon and hold in common. The ticking of the clock offers a comforting backbeat to our daily comings and goings, promoting synchrony and order where there might otherwise be disorganization or chaos. Our eagerness to keep track of the passing of minutes and hours — as much through casual glances at our screens and other timepieces as intentional planning — is unmatched in its frequency by almost any other habit...

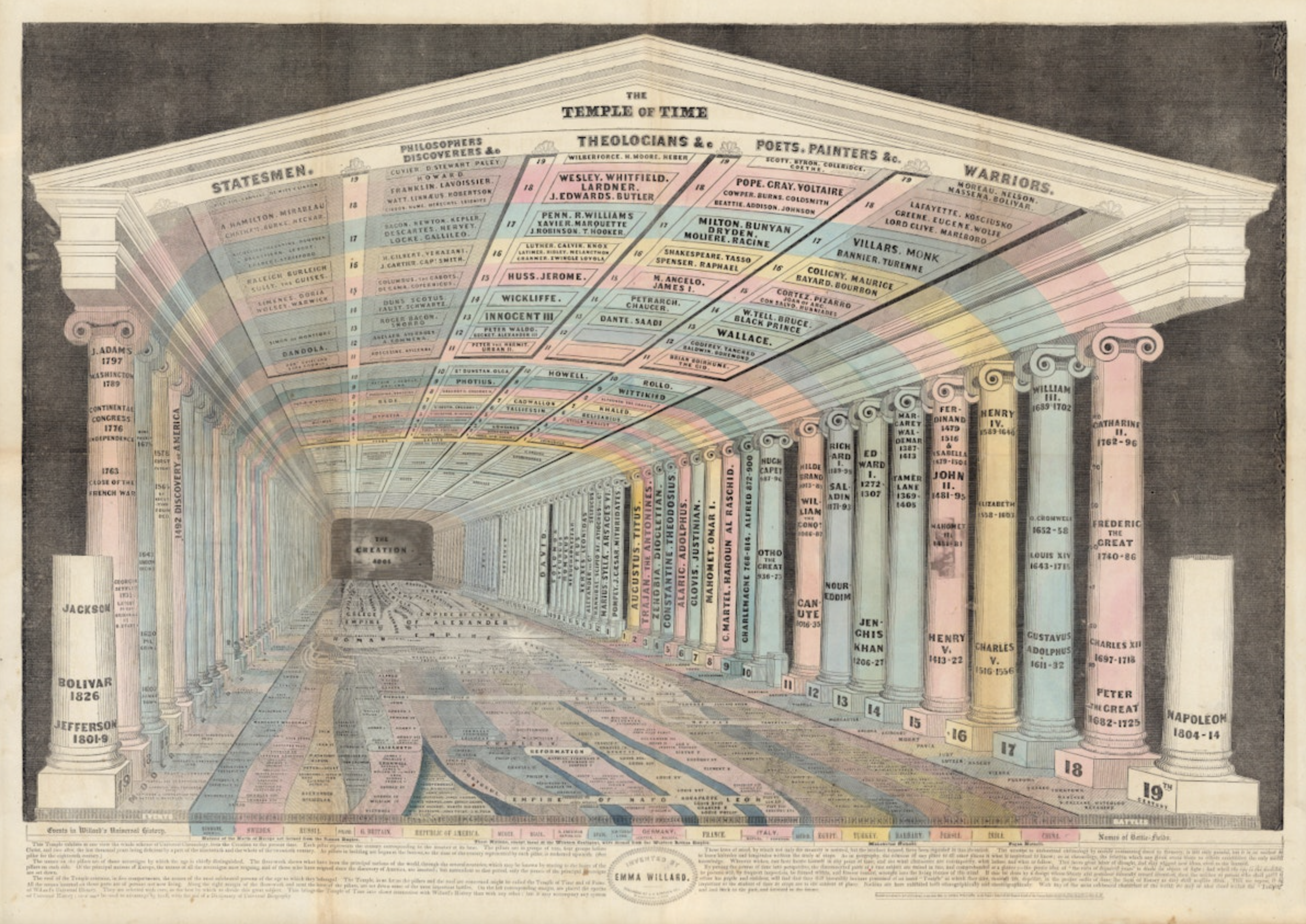

“The Temple of Time” (1846). Emma Willard.

Tuukka Toivonen September 12, 2024

Amid our species' many disagreements, the steady progression of time seems to be the one thing that everyone can agree upon and hold in common. The ticking of the clock offers a comforting backbeat to our daily comings and goings, promoting synchrony and order where there might otherwise be disorganization or chaos. Our eagerness to keep track of the passing of minutes and hours — as much through casual glances at our screens and other timepieces as intentional planning — is unmatched in its frequency by almost any other habit. There might be few moments quite as jarring as realizing one’s favored timekeeper has ground to a halt, threatening the sense of normalcy and soothing constancy afforded by clock time that our existential security seems to almost entirely rest upon. Less disorientating yet equally puzzling are the moments of flow when we become totally engrossed in soloing on the guitar, conversing with a friend or scaling up the side of a mountain, causing time as we know it to all but vanish.

Yet it is precisely these kinds of — often subtle — ruptures in one’s temporal experience that opens the door to alternative perceptions of time that can ultimately enrich our lives. Such anomalies invite active curiosity about the many mysteries and unknowns of time. Does it really progress as constantly or exist as abstractly as our attachment to machinic clock time has taught us to believe? Is time as much a co-production and outcome of life itself as it is a pace-setter? And could it be that there are cycles and makers of time that our preoccupation with the apparent precision and linearity of clock time serves to conceal? How would our lives and the way in which we partake in the more-than-human world change and expand if we explored other dimensions of time more perceptively and sensorially?

For many of us, being whisked away to a new time zone presents a type of experience that tends to fracture our sense of temporal reality quite radically — one that speaks directly to the question of how (re-)adjustment to time unfolds. We tend to normalize the sense of temporal shock by quickly adjusting our clocks to local time as soon as (or even before) we land, or by having our digital timepieces automatically adjusted for us. But our jetlagged bodies and biorhythms are not so easily persuaded, and the result is a physiological and mental sense of disorientation and fatigue at inconvenient moments. What we may not realize, however, is that the symptoms of jetlag emanate from a desynchrony of the multiple cycles we depend upon for digestion, body temperature regulation, different modes of thought, wakefulness and rest. It is therefore not the case that our acclimatization depends purely on our intentional efforts to wrestle with drowsiness — rather, it is that the complex rhythms that constitute us and the numerous symbionts we host (billions of gut microbes included) all must find a way to re-align. Restoring our “normal” sense of time and wellbeing hinges upon invisible processes through which multiple interdependent instruments — the living orchestrations of which comprise us — reach an adequate degree of synchrony and dialogue. What makes this process of readjustment truly astonishing is how it unfolds as an integrated collaboration between the vast intricacies of our biological bodies, our new environments and the way in which our home planet rotates while orbiting the sun.

As for the question of whether time marches on as precisely and exists as abstractly as we have been led to believe, exploring heliogeophysical and ecological perspectives (often neglected amid a preoccupation with physics) can help us to see a more nuanced and potent reality. First, not only do daylight hours continue to vary as the Earth travels around the sun — necessitating bodily and societal adjustments — but it actually takes the Earth slightly more than 365 days to complete one such cycle. Likewise, one rotation of the Earth on its axis does not take exactly twenty-four hours, with the Moon, earthquakes and other occurrences causing subtle fluctuations. Though imperceptible, these variations point to profound lessons about both the nature of our universe and as our own time-keeping practices and assumptions. As the historian of chronobiology and ecological restoration Mark Hall so aptly reminds us, ours is in actuality a world where “[o]rganisms do not live their lives by a metronome” but rather one where, amid constant environmental change, circadian rhythms “require continual fine-tuning” (Hall 2019, p. 385)¹. Such re-calibrations are guided by stimuli both internal and external, encompassing our solar system, our physiology as well as our social rhythms and interactions. Paradoxically enough, these multiple time-shapers that help ground our temporal experience all turn out to be far less precise and absolute than we tend to think and far more alive and idiosyncratic thanour dominant temporal cultures would imply.

“Instead of forgetting the vibrancy of living time or abandoning it in the shadow of clock time, how might you explore, and indeed celebrate, the polyphonies and polyrhythms that constitute our world and give new meaning to how time is created?”

Ecological perspectives can further enrich our understanding of time, especially if we turn to a niche group of phenologists who observe and think about the timing of diverse plant and animal species’ life-cycles. As distant as our increasingly urban and technological lives have become from the vibrant more-than-human world, most of us still retain some attachment to seasonal changes and an appreciation for their enmeshment with natural life. We intuitively realize that the appearance of swallows and other migratory birds in the Northern Hemisphere is a sign of spring (just as their return to lands in the Southern Hemisphere is taken as a sign of spring or early summer there). The blooming of certain flowers — and the simultaneous appearance of pollinators — likewise stimulates oursense of the seasons changing. The same is true of loud choruses of cicadas becoming replaced with the chirping of crickets as summer turns into autumn in places such as Japan. What phenologists have done is to bring a systematic approach to such observations of life’s cycles and developed a more refined understanding of how the rhythms of different organisms interact. For instance, flowering timings have most probably evolved with pollinators while the leaves on the same plants seem to time their cycles in relation to the herbivores that consume them. Scholars such as Bastian and Bayliss² have also brought attention to the immense value of traditional and indigenous phenological knowledges, such as calendars attuned to highly localized patterns of plant and animal life. The beauty of such calendars — that include the Japanese shi-ju-ni-ko calendar that tracks not four but forty-two seasons — is that they help bring about a sense of integration between human communities and more-than-human ecologies.

“Picture of Nations; or Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire”, (1836). Emma Willard.

In my mind, the most profound contribution of phenologists is that they show how time and its experience can be seen as collaboratively, organically constructed by multiple species, through sequences of events, interactions and degrees of synchrony. Here, the ebb and flow of life itself, its subtle orchestrations and movements, are the master time-keeper. Our mechanical timepieces and digital devices suddenly seem to offer only a vague and incomplete assessment of ‘what time it is’. Such an ecological, alternative conception of time has the power to ground our experience once again in the living world, pointing to novel possibilities for co-existence, regeneration and planetary awareness.

When we start unraveling the layers and beliefs that shape our own relationship to time, we begin to notice how entrenched notions of temporality — often linked to a need to feel productive and to conform, minute by minute, to the strictures of linear time — conceal not just how our bodies adapt to temporal disruptions and planetary movements, but an entire world of multiple times and modes of co-existence. I would now like to invite you to take a moment to reflect on how you might approach time as something that is plural, co-shaped and profoundly alive — in other words, as living time. Instead of forgetting the vibrancy of living time or abandoning it in the shadow of clock time, how might you explore, and indeed celebrate, the polyphonies and polyrhythms that constitute our world and give new meaning to how time is created? Is it possible that such an active, practical re-envisioning of time could eventually help bring more flourishing to all of the Earth’s inhabitants?

Let me leave you with a short passage from the ecological anthropologist Anna Tsing’s remarkable book, The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015), reflecting on how a full recognition of living time might allow us to generate exactly the kind of curiosity that our times require:

“Progress is a forward march, drawing other kinds of time into its rhythms. Without that driving beat, we might notice other temporal patterns. Each living thing remakes the world through seasonal pulses of growth, lifetime reproductive patterns, and geographies of expansion. Within a given species, too, there are multiple time-making projects, as organisms enlist each other and coordinate in making landscapes. The curiosity I advocate follows such multiple temporalities, revitalizing description and imagination”. (Anna Tsing 2015, p. 21.)

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.

¹ Hall, M. (2019). Chronophilia; or, Biding Time in a Solar System. Environmental Humanities, 11(2), 373–401. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-7754523

² Bastian, M., & Bayliss Hawitt, R. (2023). Multi-species, ecological and climate change temporalities: Opening a dialogue with phenology. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 6(2), 1074–1097. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486221111784

The Hermit (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 7, 2024

An old man stands with staff in one hand and a raised lantern in the other. He is lighting the dark path ahead. This is a card of hidden potential, vision, and the isolation that is necessary to realize greatness.

Name: The Hermit

Number: IX

Astrology: Virgo

Qabalah: Yod י

Chris Gabriel September 7, 2024

An old man stands with staff in one hand and a raised lantern in the other. He is lighting the dark path ahead. This is a card of hidden potential, vision, and the isolation that is necessary to realize greatness.

In Marseille, we find a wrinkled old man, with a long gray beard and hair. He holds a red staff and his lantern holds a red flame.

In Rider, we find a cloaked old man looking down, also donning a big gray beard. He raises up a lantern that contains a small star.

In Thoth, we have a more complex image, the Hermit here is not visibly human. He carries a geometric lantern with a little Sun and is surrounded by wheat. Before him is a serpent entwined egg, while Cerberus the three headed hell hound is at his feet, and along his leg, crawls a sperm in the style of Hartsoeker.

The Hermit is Virgo, and like the Lovers of Gemini, it is a sign ruled by Mercury. Both signs embody aspects of Mercury the God. Gemini is Mercurius Duplex and Virgo is the disguised Mercury from the Greek flood myth: Hermes the Hermit. Mercury, like Odin, dons a disguise when he needs to learn from the Earth. As Mercurius Duplex he comes to represent the unification of opposites like spirit and matter, masculine and feminine, life and death.

The hermit deals in seeds and seeding and, in this way, he is a magician. His letter Yod is a hand and the seed of all other letters.

The letter Yod is the seed of all other letters.

Hartsoeker's vision of sperm.

Seeds are potential, within each seed is the promise of an actualized plant. Within sperm, the human seed, is the potential for a human being. The Sperm in Thoth is a recreation of Nicolaas Hartsoeker’s vision of sperm as literally containing a microscopic human.

Just as a good farmer knows when to plant his seeds, the Hermit knows when to seed an idea, a symbol, a spell, or a word. Proper timing and placement is key. This is where the downtrodden gaze in Rider, and the Cerberus in Thoth come into play. The seeds of a Magician are not planted in soil but in the dark underground, in Hades, the Unconscious.

Alejandro Jodorowsky relates the Hermit’s number 9 to the nine months of pregnancy. The seed is buried and spends its allotted time in the dark and fertile womb.

Sometimes we need to spend time in isolation, in hermitude to be born again, to fertilize our own ideas and dreams.

The Hermit also differs from the Lovers in that the Lovers relates to copulation, while the Hermit is related to masturbation. Hermes was said to have invented masturbation, and his hermit disciples were said to worship him by masturbating. Chaos Magicians believe masturbating to the image or idea of a symbol plants it in the Unconscious.

Consider the idiom ‘sow the seed’; sowing seeds of decay, distrust, love etc. Ideas are the seeds that Mercury is most interested in. A well placed word or expression can drastically alter reality, it can save lives or end them by its utterance.

The Hermit sees the potential in all of these: ideas, seeds, and sperm. All of these that tend to be carelessly discarded are the very stuff of miracles in the hands of one who deals in potentials. He takes them up in his lantern and lights a path in the darkness of the undecided future.

When pulling this card, we may be faced with a period of boredom and isolation. This can be wasted and suffered through, or it can be a time of growth and development. We can be a seed that grows while hidden, or lay fallow. The choice is ours.

Simple Expression of the Complex Thought

Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman September 4, 2024

In his column in The New York Times, the art critic Edgar Allen Jewell wrote a review of a new show hosted by the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. He expressed his befuddlement at this distinctly modern art, devoid of figuration or tangible form, singling out the work of Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb. Yet, in an unusual act of humble awareness, he offered up the inches of his column to these same artists if they cared offer a response...

Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis. 1950-51.

Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman September 4th, 2024

In his column in The New York Times, the art critic Edgar Allen Jewell wrote a review of a new show hosted by the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. He expressed his befuddlement at this distinctly modern art, devoid of figuration or tangible form, singling out the work of Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb. Yet, in an unusual act of humble awareness, he offered up the inches of his column to these same artists if they cared offer a response. It was Barnett Newman, who had shown in the same exhibition but not been spotlighted by Jewell, who Rothko and Gottlieb came to with this offer, and Newman penned the following work that the two others signed their name to in agreement. The following essay served as a sort of defacto manifesto for this new form of American painting they were creating – a neo-expressionist style interested in myths, symbols, and emotions above all else. It first appeared in Jewell’s column in June of 1943.

To the artist the workings of the critical mind is one of life's mysteries. That is why, we suppose, the artist's complaint that he is misunderstood, especially by the critic, has become a noisy commonplace. It is therefore an event when the worm turns and the critic quietly, yet publicly, confesses his 'befuddlement,' that he is 'nonplused' before our pictures at the federation show. We salute this honest, we might say cordial, reaction toward our 'obscure' paintings, for in other critical quarters we seem to have created a bedlam of hysteria. And we appreciate the gracious opportunity that is being offered us to present our views.

We do not intend to defend our pictures. They make their own defense. We consider them clear statements. Your failure to dismiss or disparage them is prima facie evidence that they carry some communicative power. We refuse to defend them not because we cannot. It is an easy matter to explain to the befuddled that The Rape of Persephone is a poetic expression of the essence of the myth; the presentation of the concept of seed and its earth with all the brutal implications; the impact of elemental truth. Would you have us present this abstract concept, with all its complicated feelings, by means of a boy and girl lightly tripping?

It is just as easy to explain The Syrian Bull as a new interpretation of an archaic image, involving unprecedented distortions. Since art is timeless, the significant rendition of a symbol, no matter how archaic, has as full validity today as the archaic symbol had then. Or is the one 3000 years old truer? ...easy program notes can help only the simple-minded.

No possible set of notes can explain our paintings. Their explanation must come out of a consummated experience between picture and onlooker. The point at issue, it seems to us, is not an 'explanation' of the paintings, but whether the intrinsic ideas carried within the frames of these pictures have significance. We feel that our pictures demonstrate our aesthetic beliefs, some of which we, therefore, list:

Adolph Gottlieb, The Rape of Persephone. 1943.

1. To us art is an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by those willing to take the risks.

2. This world of the imagination is fancy-free and violently opposed to common sense.

3. It is our function as artists to make the spectator see the world our way - not his way.

4. We favor the simple expression of the complex thought. We are for the large shape because it has the impact of the unequivocal. We wish to reassert the picture plane. We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.

5. It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academism. There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject-matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.

Consequently, if our work embodies these beliefs it must insult any one who is spiritually attuned to interior decoration; pictures for the home; pictures for over the mantel; pictures of the American scene; social pictures; purity in art; prize-winning potboilers; the National Academy, the Whitney Academy, the Corn Belt Academy; buckeyes; trite tripe, etc.

Adolph Gottlieb (1903-1974), Mark Rothko (1903-1970), and Barnett Newman (1095-1970) were American Abstract Artists who together created a new visual language built on symbols, mythology, and color.

The Guldara Stupa (Artefact V)

Ben Timberlake September 3, 2024

The Guldara Stupa is one of the most beautiful Buddhist ruins in Afghanistan. It sits at the head of a valley on a proud spur of rock. Behind it is the remains of the adjoining monastery. The stupa is comprised of a square base with two concentric drums above it. Atop them, a dome, partially shattered and missing its spire...

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 5

Description: Guldara Stupa

Location: Logar Province, Afghanistan

Age: 2000 Years Old

Ben Timberlake September 3, 2024

The Guldara Stupa is one of the most beautiful Buddhist ruins in Afghanistan. It sits at the head of a valley on a proud spur of rock. Behind it is the remains of the adjoining monastery. The stupa is comprised of a square base with two concentric drums above it. Atop them, a dome, partially shattered and missing its spire.

The role of a stupa has been described as ‘an engine for salvation, a spiritual lighthouse, a source of the higher, ineffable illumination that brought enlightenment’¹. The design is thought to have evolved from earlier conical burial mounds on circular bases that were being built in the century before the birth of the Buddha, from the Mediterranean all the way down to the Ganges Valley. According to early Buddhist texts, Buddha himself demonstrated to his followers how to build the first stupa by folding his cloak into a square as a base, then putting his alms bowl upside-down and on top of the cloak, with his staff on top of that to represent the spire.

Ancient sculpture of the Buddha alongside a corinthian column.

The Guldara Stupa, whose name translates to ‘stupa of the flower valley,’ is the best surviving example of the sophisticated architectural developments during the Kushan period. This Empire, which flourished from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE, epitomized the cultural exchange and fusion between East and West along the Silk Road. Originally nomads from Central Asia, Kushans created a vast kingdom spanning parts of modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India. They adeptly blended elements from Greek, Roman, Persian, and Indian traditions to create a unique syncretic culture. This melding and harmonization was evident in their art, and particularly in the Gandharan style, which combined Hellenistic techniques with Buddhist themes. A Greek influence entered with Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BC and continued through subsequent Hellenistic kingdoms. Prior to this the Buddha was represented symbolically, but the Greeks introduced more human representations of the Buddha: realistic proportions, naturalistic facial features, and the contrapposto stance. Many Gandharan Buddhas appear in Greek-style clothing with wavy hair and long noses set on oval faces, typical of classical sculpture. In the sculpture here he appears sat at a banquet beside a corinthian column.

“In a single structure, philosophies and ideas from thousands of miles over converge in perfect harmony.”

The Kushans were also instrumental in the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road, patronizing Buddhist art and architecture while maintaining a religiously tolerant empire. Their capitals, like Bagram, became cosmopolitan centers where goods and ideas from China, India, and the Mediterranean world converged. Their coinage featured Greek inscriptions alongside Indian languages, and depicted both Greek and Indian deities. In governance, they adopted titles from various traditions, such as "King of Kings" (Shah-in Shah), reflecting Persian influence. This Kushan synthesis not only shaped the cultural landscape of Central and South Asia but also facilitated the transmission of ideas and technologies between East and West, leaving a lasting legacy that extended far beyond their political boundaries.

Corinthian pilasters with their Corinthian capitals.

The Guldara Stupa reflects this assimilation. The core structure is a classic stupa design that served both symbolic and practical functions in Buddhist practice. Its form represents cosmic order and the path to enlightenment, while its circular base allows for circumambulation (pradakshina), a key ritual in Buddhist worship. Yet the harmonious proportions of the square base are similar to the Temple of Hera on Samos and the engaged pilasters,with their corinthian capitals, are almost pure classical world finished in flaked local schist. In a single structure, philosophies and ideas from thousands of miles over converge in perfect harmony.

The decline of Buddhism in Afghanistan was not a sudden event but a gradual process that occurred over several centuries. While Buddhism flourished in the region from the 1st to 7th centuries CE, its influence began to wane with the spread of Islam from the west starting in the 7th century. Archaeological evidence, however, suggests that Buddhist practices persisted in some areas long after the initial Muslim conquests. The transition was not uniformly abrupt or violent, as sometimes portrayed in later folklore. Instead, there was a period of coexistence, with some Buddhist sites remaining active even as Islam gained prominence. The process of conversion was complex, influenced by political, economic, and social factors. By the 11th century, Islam had become the predominant faith in the Kabul region and most of Afghanistan, though pockets of Buddhist practice may have survived in remote areas.

The abandonment of many Buddhist sites was likely due to a combination of factors, including changing patronage patterns, shifts in trade routes, and the gradual adoption of Islam by the local population. Interestingly, some Buddhist architectural and artistic elements were incorporated into early Islamic structures in the region, reflecting a degree of cultural continuity amid religious change. The last definitive evidence of active Buddhist practice in Afghanistan dates to around the 10th century, marking the end of a remarkable era of religious and cultural flourishing that had lasted for nearly a millennium.

Ben Timberlake at the Guldara Stupa.

It was Guldara’s remote position that probably accounts for its remarkable preservation. In the 19th century it was looted by the British explorer and archaeologist Charles Masson. (It’s a little mean to use the word ‘looted’: he ‘opened’ the stupa looking for relics and artifacts as was the practice at the time). Masson was a fascinating character. His actual name was James Lewis but he deserted from the East India Company’s army in 1827 and adopted the alias Charles Masson. He spent much of the 1830s living in Kabul, travelling the country extensively and documenting the Buddhist archaeological sites there. His work was crucial in bringing these sites the attention of Western scholars. Guldara was his favourite, “perhaps the most complete and beautiful monument of the kind in these countries’.

I visited Guldara this July. It is an hour’s drive from Kabul to the village at the head of the valley, then another 20 minutes up the dry riverbed that tested our 4x4, and finally a half an hour’s trek up to the site itself. There is something deeply spiritual about the Stupa. It seems to belong profoundly to the place - to the valley - and yet floats above it. Its lines and proportions are as graceful as the surrounding mountains while its myriad of eastern and western architectural forms have integrated to be more than the sum of their parts. It is a site of quiet conjunction, of perfect harmony. Of peace.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

¹ The Buddhas of Bamiya, Llewelyn Morgan.

The Queen of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 31, 2024

The Queen of Wands is a court card, and the second highest in the suit of Wands. In each iteration we find our Queen, enrobed, crowned, and bearing a Wand. This is a card of aggression and desire...

Name: Queen of Wands

Astrology: Aries, Water of Fire

Qabalah: He ה of Yod י

Chris Gabriel August 31, 2024

The Queen of Wands is a court card, and the second highest in the suit of Wands. In each iteration we find our Queen, enrobed, crowned, and bearing a Wand. This is a card of aggression and desire.

In Marseille, we find the Queen looking down, her golden wand’s base in her lap, a symbolic phallus. Her long hair and robes flow about her. Both of her hands are at her waist.

In Rider, we find the Queen on a throne adorned with lions. Her right hand bears her wands and her left a Sunflower. Below her stage sits a little black cat. She is a young woman with a demure gaze.

In Thoth, we find the Queen inflamed. Her hair is made of fire that give way to the flames all around her. She looks directly down. Her crown is topped by a hawk, and her wand by a pinecone. She is petting a cheetah.

The Queen of Wands is a card of duality - fire and water, aggression and love, innocence and experience.

A phrase that comes to mind is “Cute Aggression”, the urge to squeeze and bite cute things without actually wanting to cause harm. It’s a confusion of two drives, maternal love and aggression. This is the nature of the Queen of Wands, the struggle between these drives.

Aries is the first sign and known as the “baby of the zodiac”, it is just learning how to exist. Kittens bite and scratch, without any malice, in acts of innocent violence: this is the domain of the Queen of Wands. Animal aggression can be read as the Saturnian child devouring drive, or as the innocent violence of Aries. One wants to maintain power, while the other is trying to gain power.

This follows with the twin of violence, sex. The development of sexuality through aggression, which appears as teasing and name-calling, is opposed to the aggression that expresses itself sexually.

This is the domain of the Queen of Wands who balances these things in her hands, the wand and the flower, the masculine and the feminine, the phallus and yoni.

This card often can indicate a person, often an Aries, but generally a very dominant woman unafraid to express her opinions.The card is the elemental inverse of the Knight of Cups, who balances water and fire, but chooses confused chastity that keeps his heart pure at the cost of his aggressive will, whereas the Queen of Wands takes on the far more difficult task of approaching the world willfully while fighting to keep her heart pure.

When we pull this card, we are often met with this same dilemma, the balancing of love and will. The Queen is telling us “And whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not unto men;”

Towards Alienation

Arcadia Molinas August 29, 2024