What Do The Fungi Want?

Tuukka Toivonen May 14, 2024

Creative ideas grow, mutate and flourish through conversations between people. However casual or mundane, these exchanges have the potential to reveal novel possibilities, or dramatically shift the course of a fledgling idea. Direct interactions are a tremendous source of motivation for creators. The best ones possess a much-overlooked generative power…

Fly Agaric Watercolor, 1892. Leigh Woods.

Tuukka Toivonen May 14, 2024

Creative ideas grow, mutate and flourish through conversations between people. However casual or mundane, these exchanges have the potential to reveal novel possibilities, or dramatically shift the course of a fledgling idea. Direct interactions are a tremendous source of motivation for creators. The best ones possess a much-overlooked generative power.

This was the basic premise of the research I was involved in as a sociologist until, a few years ago, I stumbled across interspecies creativity. I had become intrigued by how certain colleagues – designers and artists, especially – spoke passionately about how they sought to ‘create with and for nature’ or even ‘as nature’ when making new textiles, garments or artworks. They felt strongly that it was time to start treating living organisms and ecosystems as genuine collaborators and co-creators in their process.

Atlas des Champignons (1827). M. E. Descourtilz,

Spellbound by the prospect of novel ideas and designs emerging from humans collaborating with algae, mycelium and slime mould, I started to wonder about the practical and philosophical implications of such phenomena. For me, the question was not only about understanding the material qualities of particular organisms, it was about how humans might transform themselves into genuine co-creators in relation to nonhumans.

The notion of ‘creating with nature’ can be confounding – it was for me. Beyond the crude physical barriers that keep nonhuman and human lives separate, prevailing worldviews order us to place animals, plants, insects and fungi in a fundamentally different category from humans who – whilst animal – have developed complex cultures, technologies and societies, making us ‘unstoppable’, even ‘superior’. As a result of this human-centric conditioning, we are hopelessly unaccustomed to viewing nonhuman life as intelligent. Experts of human organizational life argue that perspective-taking – in essence, making an effort to imagine the point of view of another person or persons – is key to successful communication and management, and even constitutive of our ability to be ‘fully human’. There is no such chorus calling us to seriously listen or sensitize ourselves to the perspectives of nonhumans.

To explore species-crossing creativity further (in the hope of transcending or ameliorating the non/human barrier), we decided to hold in-depth conversations with a dozen biodesigners and bioartists, as well as a few progressive entrepreneurs. The creators were growing sneakers with bacteria that produce nanocellulose, working with microalgae to purify water contaminated by fashion dyes, and sewing fabrics from wild plants, among other fascinating experimental practices.

One outspoken participant explained that, in the early stages of the creative process, he always sought to engage as directly and viscerally with a living organism as possible, relentlessly looking for promising ways to collaborate. Having developed a particular interest in working with mycelium at a mass scale, he soon became curious not only about the material co-design possibilities of this organism, but also its behaviours and its needs. A simple yet pivotal question emerged: ‘What does the fungi want?’ His next steps as a designer and entrepreneur would be derived from that simple query.

Nearly all the creators we spoke to expressed an active curiosity about the needs of the organisms they were engaging with. Working with diverse plant species as well as digital technology, one participant recounted how she explored the way plants sense the world, their sensitivity to light and sound, and their ways of communicating with other organisms. Another spoke of the profundity of learning to collaborate with organisms whose existence on earth predated that of humans by millions of years.

“By subtly observing and interacting with diverse organisms, creators can establish equality of existence with all forms of life.”

The Intruder (c.1860). John Anster Fitzgerald.

What does it mean, really, to think in terms of what a nonhuman organism ‘needs’, ‘wants’ or ‘likes’? Do such queries belie a deeper significance, an alternative way to view human-nature relations?

The visionary work of the British anthropologist Tim Ingold may help us understand why inquiring into the ‘needs’ and ‘wants’ of organisms is not just naïve anthropomorphism. In his discussion of how the people of the North American Cree Nation situate themselves in relation to their surroundings, Ingold uncovered a relevant mode of being that transcends central dichotomies that govern our (Western) thinking with regards to nonhuman life:

“From the Cree perspective, personhood is not the manifest form of humanity; rather the human is one of many outward forms of personhood. And so when Cree hunters claim that a goose is in some sense like a man, far from drawing a figurative parallel across two fundamentally separate domains, they are rather pointing to the real unity that underwrites their differentiation” (from Tim Ingold’s The Perception of the Environment, 2001).

Ingold explains that, unlike Western approaches that begin from an assumption of fundamental difference between humans and animals (leading us to search for possible analogies and anthropomorphisms, describing many animal behaviours and features in terms of their resemblance to humans), indigenous communities have typically done the opposite: starting from an assumption of similarity. For this reason, in such communities “it is not ‘anthropomorphic’ […], to compare the animal to the human, any more than it is ‘naturalistic’ to compare the human to the animal, since in both cases the comparison points to a level on which human and animal share a common existential status, namely as living beings and persons”. It is owing to this holistic worldview that the Cree assign personhood and utmost value to animals, forests, rivers and other parts of the living world, the all-important commonality with humans being their aliveness, animateness, or their potential to become an animate being.

And so we find that hidden inside our question – what does the organism need? – lies an entirely different, non-dichotomous approach to being. Indeed, by subtly observing and interacting with diverse organisms, creators can establish equality of existence with all forms of life.

It is not that we should believe that fungi or microalgae – or larger animate entities such as rivers or lakes – possess a will or preferences exactly like those of humans. Rather, it is that through these acts of curiosity and questioning, we place ourselves on a single life plane, opening up space for genuine interaction. . From this vantage point, asking ‘what does the fungi want?’, is a radical act in the context of a technological society, contesting the deep dichotomies of ‘modern’ life. Importantly, adopting this orientation rejects the totalizing tendency to position science as the only legitimate route to gaining knowledge, by restoring our ability to enter into direct, unmediated and authentic relations with other forms of life. This way of questioning can take us a surprisingly long way towards transforming ourselves into genuine collaborators and co-creators for other species.

So, what did the fungi want? In the case of the particular designer mentioned earlier, one Bob Hendrix, the answer turned out to be that they wanted to digest and recycle organic matter, specifically, humans. That insight led the designer down a path of developing mycelium-based coffins, with a view to helping humans to become useful, welcome participants in more-than-human ecosystems at the end of their lives, gifting life-giving soil with precious nutrients and energy.

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - May 1, 2015

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

The World (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 11, 2024

The World card is a cosmogram, meaning it depicts the whole of the cosmos. We find a naked woman floating within a ring, her legs crossed and something flowing about her. She is Maya, the embodied force of creation and illusion. Her dancing and spinning manifests the material world. The Four Cherubs frame the corners as symbols of the states of matter…

Name: The World

Number: XXI

Astrology: Saturn

Qabalah: Tau ת

Chris Gabriel May 11, 2024

The World card is a cosmogram, meaning it depicts the whole of the cosmos. We find a naked woman floating within a ring, her legs crossed and something flowing about her. She is Maya, the embodied force of creation and illusion. Her dancing and spinning manifests the material world. The Four Cherubs frame the corners as symbols of the states of matter. This card, while containing lofty spiritual imagery, pertains to mundane material reality.

In Marseilles, our lady has a wand and a red/green sash. She is smiling and looking down. In the corners sit a winged angel, an eagle, and a lion, each of them bearing a Nimbus. Only the Bull, the Cherub of Earth, is uncrowned. The ring is a blue wreath with yellow ties, set on a pure white background.

In Rider, she has two wands and a gray, saturnine sash. She has a Mona Lisa smile and is looking down. Here the Cherubs are emerging out of clouds and have no nimbus. The ring is vegetable green with red ties and the card is set on a blue sky.

In Thoth, we have a drastically different image. World gives way to the vast Universe and the lady is no longer human, but living gold. Her sash is a serpent, and she is dancing. The Cherubs appear almost as a fountain structure, pouring fourth energy. The ring is the perspective of a round sky, the wheel of the Zodiac, and the endless stars beyond. The card is set on a resurrected Saturn, no longer dead, but verdant. The eye of God is looking down at the motions within the ring, and below is the geometric emanation of these lofty elements.

How are we to make sense of this beautiful but complex imagery?

Let’s start with a sort of spiritual “math”. Just as our journey through the Major Arcana begins with airy Zero, here we find the empty hole of the number filled in by material reality. Potential becoming actualized.

0=2, as the magicians declare. Nothing is lonely, and in it’s loneliness begets difference. By dividing itself into what we call light and dark, good and evil, night and day, masculine and feminine, it creates the tension necessary for the theater of existence.

And of course it doesn’t stop there, two makes itself four, and on and on until we have our endlessly varied World.

The sash is the serpentine, spiraling energy of creation and the direction of this divine expansion flows along

The Cherubs are the four Living Creatures of Ezekiel, the four elements, and the four fixed signs of the Zodiac. They are the divided Tetragrammaton:

The Lion is Leo and Fire

The Eagle is Scorpio and Water

The Angel is Aquarius and Air

The Bull is Taurus and Earth

These four elements, as our study of tarot will make clear, make up reality itself. We can bring this to a more scientific view, as we often struggle with differentiating the Philosopher’s elements from mundane elements.

Water is not H20, but all liquids, Earth is not dirt, but all solids, etc. The philosophical elements are states of matter and their corresponding mystical significance.

In this way, this card provides a view of all physical reality.

When we draw this card, we are often reaching a standstill, a moment of pause to look at ourselves, our actions, and our world from the distance of the heavenly machinations that form it.

Questlove Playlist

EdgrWrght: The Wonder Workout

Archival - May Afternoon, 2024

Questlove has been the drummer and co-frontman for the original all-live, all-the-time Grammy Award-winning hip-hop group The Roots since 1987. Questlove is also a music history professor, a best-selling author and the Academy Award-winning director of the 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941492710?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Interview de Thelonious Monk"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

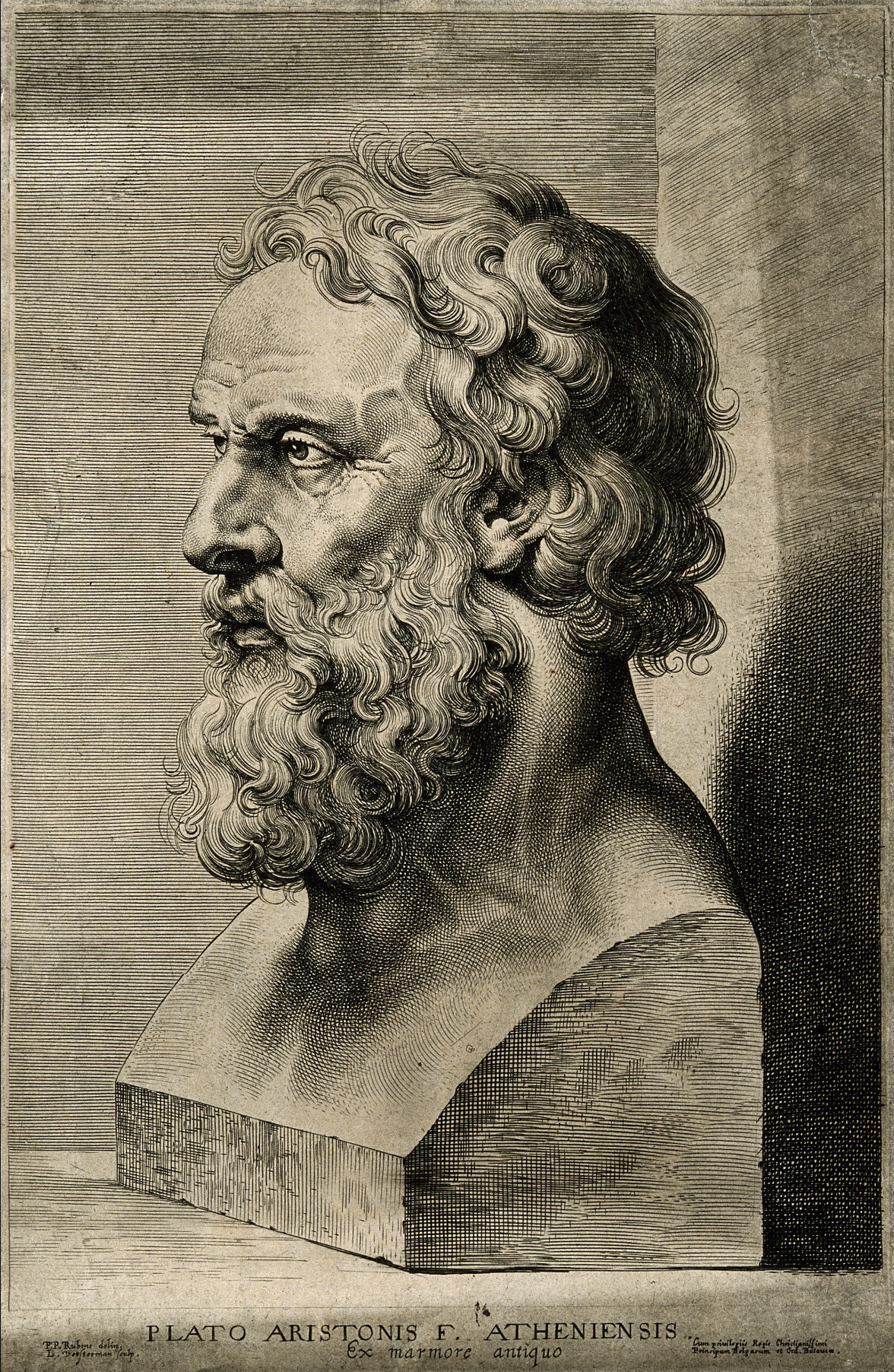

Footnotes to Plato (c.428-347BC)

Nicko Mroczkowski May 9, 2024

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name…

Rafael's School of Athens, 1511.

Nicko Mroczkowski May 9, 2024

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name.

In this flourishing new culture, thinkers began to try and understand the world in a more organised way. From this, Western philosophy was born, and science came along with it. These thinkers asked themselves: what is the world made of, and how does it work? This was not a new question, most likely every culture before had asked it in some way, but what made the Ancient Greeks unique was their systematic approach. Because they also asked a secondary question, which, arguably, is still the starting point of any scientific inquiry: what is the correct way to talk about what something is?

L. Vosterman, after Rubens. c. 1620.

Each of the very first philosophers answered this question with one thing: ‘substance’, or stuff. They believed that the right way to understand the world is in terms of a single type of matter, which is present in different proportions in everything that exists. Thales of Miletus, perhaps the earliest Greek philosopher, believed that all things come from water; solid matter, life, and heat are all special phases of the same liquid. For him, then, the true way to talk about an apple, for example, is as a particularly dense piece of moisture. Heraclitus, on the other hand, believed that everything is made of fire; all existence is in flux, like the dancing flame, of which an apple is a fleeting shape.

We don’t know much more about these thinkers, as not much of their work survives; most of the accounts we have are second hand. We only know for sure that each proposed a different ultimate substance that everything is made out of. Then, a little while later, along came a philosopher called Plato.

Despite its prominence, ‘Plato’ was actually a nickname meaning ‘broad’ – there is disagreement about its origin, but the most popular theory is that it comes from his time as a wrestler. His real name is thought to have been ‘Aristocles’. Whatever he was really called, Plato changed everything. Instead of arguing, like his predecessors, for a different kind of ultimate substance, he observed that substance alone is not enough to explain what exists: there is also form. In other words, he more or less invented the distinction between form and content.

One could spend a lifetime analysing these terms, and there are whole volumes of art and literary theory that address their nuances; but it’s also a common-sense distinction that we use every day. The form of something is its shape, structure, composition; the content, or substance, is the stuff it’s made of. So the form of an apple is a sweet fruit with a specific genetic profile, and its content is various hydrocarbons and trace elements. The form of a literary work is its style and composition – poetry or prose, past or present tense, first- or third-person, etc. – and its content is its subject matter, what it describes and what happens in it.

An attempt at a classification of the perfect form of a rabbit. (1915)

We can already see Plato’s influence on modern knowledge in these examples. The correct way to talk about something, for him, was primarily in terms of its form, and only secondarily in terms of its substance. This is still the case for us today. There is a powerful justification for this preference: it allows us to talk about things generally. This is basically the foundation of any science; we would get absolutely nowhere if we only analysed particular individuals. There are just too many things out there. No two animals of the same species, for example, will ever have exactly the same make-up – even if they’re clones. They have eaten different things, had different experiences; they also, quite frankly, create and shed cells so rapidly and unpredictably that differences in their substance are inevitable. What they do have in common, though, is their anatomy, behaviour, and an overall genetic profile that produces these things.

Forms are peculiar, however, because they don’t exist in the same way as substances do. While there are concrete definitions of substances, the same cannot be said for forms. There are, for example, no perfect triangles in existence, and we could probably never create one – zoom in enough, and something will always be slightly out of place. So how did Plato come up with the idea of something that can never be experienced in real life? The answer is precisely because of things like triangles. Mathematics, and especially geometry, is the original language of forms, and it can describe a perfect triangle or circle, even though one may never exist. The success of mathematical inquiries in Plato’s time allowed him to recognise that the concept of forms which worked in geometry can be applied to understand the world more generally.

Forms are perfect specimens of imperfect things, are exemplars, or things we aspire to – they are the way things ought to be, in a perfect world. ‘Form’ in Plato’s work is also sometimes translated as ‘idea’ or ‘ideal’. And so, Plato’s answer to the question of how to conduct scientific inquiry was this: the correct way to talk about something is in terms of how it should be. Despite our imperfect world, rational thinking – the capacity of the human mind for grasping things like mathematical truths – can do this, and that’s what sets human beings and their societies apart from the rest of nature.

Perfect Platonic Solids

It gets a little strange from this point on: Plato believes that forms really exist, but in a separate, perfect world. Our souls start out there and then make their way to the material world to be born, but still have implicit knowledge of their original home, and this is where reason originates. Improbable, yes, but not completely absurd. Plato was clearly trying to explain, to a society that was just beginning to understand the importance of perfect knowledge, how it could exist in our imperfect world of change and difference. Two millennia later, Kant would show that it’s due to the way the human mind is structured, but we don’t really know how this happened either.

Really, we’re still playing Plato’s game. The basic realisation that to know the world, we must study the general and the perfect, and ignore the non-essential characteristics of particular individuals – this is his legacy. Of course, this way of thinking is so deeply ingrained in Western culture that it can be hard to grapple with; it’s so fundamental that we take it for granted. But what we call knowledge today would not be possible at all without it. Seeing this, we can imagine what the influential British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead meant when he wrote that ‘the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists in a series of footnotes to Plato’.

Nicko Mroczkowski

Chris Pine

1hr 32m

5.8.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with actor Chris Pine about reaching a flow state in art.

<iframe width="100%" height="75" src="https://clyp.it/m2ngpdkj/widget?token=c9990ff05247ba6edd04ad0257eb8e58" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Children’s Drawings

Ale Nodarse May 7, 2024

Children’s drawings abound. They have few dates and fewer titles, but nonetheless they pile up. Assembled on fridges or tucked away in shoeboxes, they belong to a world of their own. It’s a world they, with few inhibitions, create –– and a world which is fragile. If such drawings survive, it’s most often because they have been saved by someone else. In other words, if drawings from your childhood survive, then you most likely have someone to thank…

Ale Nodarse May 7, 2024

Children’s drawings abound. They have few dates and fewer titles, but nonetheless they pile up. Assembled on fridges or tucked away in shoeboxes, they belong to a world of their own. It’s a world they, with few inhibitions, create –– and a world which is fragile. If such drawings survive, it’s most often because they have been saved by someone else. In other words, if drawings from your childhood survive, then you most likely have someone to thank.

Children’s drawings may be quaint, but they are powerful, too. In Bologna, in 1882, an Italian archaeologist and art historian called Corrado Ricci took shelter from the rain beneath a covered archway. That portico, to Ricci’s amazement, was filled with adolescent scribblings, with graffitied words and drawings. Here was a “permanent exhibition of literature and art” — one of rare modesty and more than occasional impropriety¹. The exhibition moved him and led him to collect children’s drawings, assembled in a book titled ‘The Art of Children’ (L’arte dei bambini). Lamenting the drawings’ anonymity, Ricci was determined to trace their history. The Art of Children is replete with works from his collection. It charts a course from first lines to full figures and makes a case for the life of a child’s mind. It charts, as well, the beginnings of a particular branch of developmental psychology. One in which, for instance, a “Table and Chair” becomes a proof of spatial cognition; and where a quickly dashed “Sun” rises in attestation as if to say: Observe the work of a child, year six.²

Human children have drawn for millennia (and so, quite likely, did their neanderthal cousins)³. Remarkable though it is, this fact ought not surprise us. Ricci’s revelation, that such drawings have much to teach us, did however seem surprising (at least to many of his peers). Turning away from the product of children’s drawing to the process of its collection (on the fridge or in the shoebox), we might wonder: What causes us to marvel at a child’s drawing in the first place?

This act of marveling has a history. One of the earliest images of a child’s drawing was not by a painter, but by an archaeologist and antiquarian. That painting, Giovanni Caroto’s c. 1515 Portrait of a Boy With Drawing, is marvelously strange.⁴ Strange, given that children were rarely depicted apart from their parents — as having their own distinct lives.⁵ And stranger, still, because this child holds a drawing. Curving slightly at the grasped edge, the paper reveals a standing figure, a partial head, and, just above the boy’s thumb, an eye placed in profile.

Why set such a drawing in painting? Scholars have sought a familial link between the artist and the boy.⁶ His carrot-colored hair has provoked speculation that he is indeed the artist’s son (or younger nephew), namely since Caroto means “Carrot.” But Caroto’s other vocation remains suggestive. As an archaeologist, he spent years compiling a list of the antiquities in his hometown of Verona, tasked with the setting of “timeless” fragments back into time.⁷ Viewed as testimonies of human creation, every fragment –– drawn and discovered –– could be beheld as eloquent. Whether made by his relative or not, Caroto found the boy’s drawing worthy of similar preservation.

Children’s drawings, a marvel in their own right, raise a question that children do not ask. What do we — looking back, looking ahead — consign to loss? And what do we save?

¹Corrado Ricci, L’arte dei bambini (The Art of Children) (Bologna: Zanichelli, 1887), 3–4.

²Helga Eng, The Psychology of Children's Drawings: From the First Stroke to the Coloured Drawing (London: Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., 1931). (Fig. 62, reproduced from her text.)

³Jean-Claude Marquet (et al.), “The Earliest Unambiguous Neanderthal Engravings on Cave Walls: La Roche–Cotard, Loire Valley, France,” PLoS ONE (2023): 1–53.

⁴The painting, made with oil on board, is kept at the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona, Italy.

⁵Phillipe Ariès, Centuries of Childhood, 43. Ariès proposed, not without significant controversy, that the turning point for the representation and understanding of the child as such was the beginning of the seventeenth century. .

⁶Francesca Rossi (et al.), Caroto (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2020), 134.

⁷Caroto captured Verona’s antiquities through a series of engravings first published in 1540, with a text by antiquarian and humanist Torello Saraina.

Alejandro (Ale) Nodarse Jammal is an artist and art historian. They are a Ph.D. Candidate in History of Art & Architecture at Harvard University and are completing an MFA at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art. They think often about art — its history and its practice — in relationship to observation, memory, language, and ethics.

Film

<div style="padding:41.24% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941483162?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The Castle of Sand clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Tyler Cowen Playlist

Choral Music

Was the human voice the very first musical instrument? I don’t know, but I expect it will end up as the very last one. In the meantime, the choral pieces people have been producing amount to one of music’s most underexplored traditions.

Tyler Cowen May 6, 2024

Was the human voice the very first musical instrument? I don’t know, but I expect it will end up as the very last one. In the meantime, the choral pieces people have been producing amount to one of music’s most underexplored traditions.

Tyler Cowen is Holbert L. Harris Chair of Economics at George Mason University and serves as chairman and general director of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. With colleague Alex Tabarrok, Cowen is coauthor of the popular economics blog Marginal Revolution and cofounder of the online educational platform Marginal Revolution University.

Strength (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 4, 2024

Strength depicts a woman with power over a lion. She has overcome this extremely dangerous beast by means of influence and control, though each deck posits a very different form of control…

Name: Strength, Force, Lust

Number: XI or VIII

Astrology: Leo

Qabalah: Teth ט

Chris Gabriel May 4, 2024

Strength depicts a woman with power over a lion. She has overcome this extremely dangerous beast by means of influence and control, though each deck posits a very different form of control.

In Marseilles we find a well-dressed noble woman opening the mouth of the lion. She is smiling. While one hand is opening his mouth, the other is in front of it, revealing her degree of control. The lion’s eyes, like his mouth, are wide open, he looks up as she looks down. The card is called “La Force”, the force being that bestial force of the lion, and the taming, civilizing, force of the woman.

In Rider, we see a similar image. Our lady here is dressed in white and adorned with flowers. She is crowned by infinity, an explicit mirroring of the hat in Marseilles. The lion here is far more tame, almost reduced to a dog, licking at her happily, with his eyes closed. She is closing his mouth. This card is called Strength, which is the strength of the woman to close the lion’s mouth, and of course, the physical strength of the lion himself.

In Thoth we are given a drastically different image, and evocative name, Lust. Here we have a reinterpreted scene from Revelation: the Whore of Babylon and the Great Beast. Moving beyond the repressive, chaste attitudes of the past two cards, here the woman controls the lion from on top. She has reigned the beast, and rides him. She is naked and bearing a cup, and the beast not only has many faces, but a serpentine tail (the Serpent is the ideogram of Teth).

The profound differences across these decks reveal just how significant this particular card is.

This is a card about Sex. Of course one can interpret these means of control as they appear in relationships, but this is a mystical art, and the important work here is understanding how this relates to self control.

The Freudian Libido, immense and dangerous, is given an emblem here. In the past, repression or chaos were our only options for dealing with this energy.

We tame the beast, or we are devoured by it. The radical, psychoanalytic development of sublimation, is shown in Thoth. Here we are given the option to not simply repress and subdue our animal urges, but to ride them where we will. Primal drives are the most powerful forces of nature, effectively directing them means harnessing a great power. Yet, this is difficult and dangerous thing, so much so that we even have a phrase for it: riding the tiger.

This is a card of creative and developmental energies, how they can overwhelm us, and how to understand and utilize this overflow.

When dealt this card, we are to consider our own creative energies, our sexuality. One can often expect an influx of these! And how will you deal with it? Use force to tame it, spiritual strength to control it, or ride the tiger of lust?

Hannah Peel Playlist

Tree of Life

Archival - April 22, 2024

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941494171?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The toy shop Jules Engel"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Boltzmann Brains — 1. Chaos in the DVD

Irà Sheptûn May 2, 2024

If you want to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe…

Celestograph, 1893. August Strinberg.

Irà Sheptûn May 2, 2024

“If you want to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.” Carl Sagan

Let’s pretend it’s 2006. You’ve just come back from the kitchen to continue watching a movie on DVD. The screen has now faded to black and the DVD logo is bouncing slowly from wall to wall in the box of the screen. You observe over time, the logo hits many different points within the rectangle of the box. One wouldn’t be alone in wondering how often the DVD logo will lock perfectly into one of the corners of the screen before bouncing back again. Naturally, this varies depending on the pixel size of the screen as well as the logo itself and its fixed velocity, but for a standard NTSC-format DVD Player with 4:3 aspect ratio, we can approximate the phenomenon to occur roughly every 500 – 600 bounces, or once every 3 hours. Now, suppose we blew up our screen slowly to the size of the observable universe, how often would we score a perfect corner lock-in then? The idea becomes completely absurd: we can all safely agree the probability is inconceivably, astonishingly tiny. But not impossible.

Celestograph, 1893. August Strinberg.

In the latter half of the Nineteenth Century, physicists were busy laying the foundations of what we now understand as statistical thermodynamics – the art of using the rules that govern the very small components of a system that are probabilistic in nature, to build up a clear picture of the system’s behaviour in general. These small components (individual particles amongst many) have position and momenta that are constantly changing. It is useful to think of a closed system as a new deck of cards, with each particle represented by a single card in the deck. A central concept of statistical thermodynamics is entropy, often synonymous with disorder, where higher entropy systems are subject to greater randomness and uncertainty in their behaviour. If I were to take a random card and place it somewhere else in our new deck as you observed, you’d probably have an easier time reverting the deck back to its original order than if I shuffled it thoroughly. You might say the one-card rearrangement is of lower entropy than the thoroughly shuffled deck, due to the degree of disorder inherent to the shuffling of the cards from their standard order, right? Well, you’d be correct! There are many more possible configurations in our higher entropy shuffled deck that are all equally likely compared to any one-card manoeuvre. However, this description of entropy as a measure of disorder can often be misleading, as we’ll soon discover.

Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann, who alongside his contemporaries, was concerned with understanding how the properties that define the state of a closed system (such as average energy, temperature, or pressure) could be interpreted from the more probabilistic behaviour of the individual particles that make up a given thermodynamic process. The Second Law of Thermodynamics says that the entropy of a closed system can only stay constant or increase over time. Boltzmann contested that perhaps entropy could be thought of more as a statistical property – the chances of staying the same or increasing are high, however the chances of decreasing are not zero, subject to behavioural fluctuations in the particles of the system. Recall our shuffled deck of cards: it’s highly unlikely to return to its original order through constant random shuffling, but the possibility must occur with infinite time!

“The system experiences a fluctuation to lower entropy; an ordered state arising from a more disordered one.”

One might now see how the description of entropy as a measure of disorder can cause some problems. Let’s say we have a deck of cards arranged by suit, and another arranged by increasing number. Which is more inherently entropic? Both decks are undeniably examples of a certain order within their own closed systems. If we accept that both are rearranged from the same initial structure, one must have higher entropy than the other to account for the number of rearrangements to get the structure it is now in. In this way, we can properly define entropy as a measure of the number of ways you can arrange these particles without changing the overall state of the system. In other words, how many ways can I shuffle the deck without adding new cards or taking any away?

Celestograph, 1893. August Strinberg.

But wait! Aren’t these so-called entropic fluctuations to order not a gross violation of the Second Law? If entropy is a statistical property, these fluctuations become inherent to the nature of the Second Law and not a violation, because the net direction of entropy will still tend to increase. Returning to our DVD Player (assuming that the little DVD logo travels around the box with random motion) we can say our closed system will increase in entropy as with every wall bounce the DVD logo makes as it loses predictability in its path. Over infinite time, all possible positions of the DVD logo in the two-dimensional box will be true, and shall increase steadily in entropy with every bounce.

But what of our exciting statistically improbable instances where the logo perfectly locks into a corner? According to Boltzmann, in these instances, the system experiences a fluctuation to lower entropy; an ordered state arising from a more disordered one. However, this is all still outweighed by the increasing net entropy of our DVD Player; the energy used up to power our little dancing logo on its journey of increasing uncertainty, and the heat expended by its humble efforts’ ad infinitum. With this same reasoning, Boltzmann introduced new ideas around the nature of our early universe and how it came to be well before the formulation of Lemaître’s theory of the Primeval Atom, or as it’s now known, The Big Bang Theory.

Now, try to imagine a vast cosmos, infinite in age. All the different regions of this system have more or less reached an equal share of energy: it is uniformly distributed, or what we call in Thermal Equilibrium. At this stage in the lifecycle of a cosmos it has reached maximal entropy, or Heat Death. As we know, it’s not impossible for such infinitely large systems to experience large fluctuations. Given the infinite age of this cosmos, any statistically unlikely event (no matter how improbable) must be true. It is not impossible that one of these local regions in space and time might fluctuate just enough from maximal entropy to form a new ‘world’, if only for a short period of aeons. This new ‘world’ might be indistinguishable from the world that you and I live in; a lower-entropy state of unspent energy and potential, arising by sheer improbability, from an otherwise vast and dead cosmos, trapped in maximal entropy.

There is a chance, then, that we are ‘the moment’ in the truest sense of the term. Could we be special and lucky enough to exist within such an unlikely ‘new world’? Could ours be the moment the DVD logo locks perfectly into the corner of the screen - a Boltzmann Universe?

Marianne Williamson

1hr 23m

5.1.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with Marianne Williamson about ‘Miracle Mindedness’

<iframe width="100%" height="75" src="https://clyp.it/p42mxxml/widget?token=e8488bba20cc252565f2d2003ea4585e" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:67.8% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941492722?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Martin Scorsese on Kubrick's 2001 A Space Odyssey and D.W. Griffith"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Nonviolent Communication - Our Brains, Stereotypes, and Strategies

Wayland Myers April 30, 2024

Fifteen years ago, learning that I'd written a book on Nonviolent Communication, my wife's Community Nursing professor asked if I would come to the community clinic and share some of what I knew about NVC with a small group of men. They were beginning the process of reintegrating themselves into civilian life after having completed multi-year prison sentences and a six-month stint in halfway houses. The evening was part of a support program made available to them and I was keen to share some of the wisdom and humanity I’ve derived from this unique framework for helping people create compassionate connections with others and themselves.I readily agreed...

Fragment from an 18th Century Memento Mori, Poland

Wayland Myers April 30, 2024

Fifteen years ago, learning that I'd written a book on Nonviolent Communication, my wife's Community Nursing professor asked if I would come to the community clinic and share some of what I knew about NVC with a small group of men. They were beginning the process of reintegrating themselves into civilian life after having completed multi-year prison sentences and a six-month stint in halfway houses. The evening was part of a support program made available to them and I was keen to share some of the wisdom and humanity I’ve derived from this unique framework for helping people create compassionate connections with others and themselves.I readily agreed.

When preparing for talks like this one, I think about the particular audience I'll be speaking with and try to imagine which parts of NVC they might find interesting and relevant. When I thought about what to share with these men, I drew a blank. I also unhappily discovered that when thinking about the evening with them, I felt anxiety about how the evening might go far more than I usually do. What was going on?

It wasn’t until recently, when in preparation for writing a new book on NVC of which these articles are a part, that I explored the most recent findings concerning how our brains work and discovered that the strength of my anxious feelings wasn’t my fault. Particular brain structures and neurological processes that bestowed the most survival and reproduction advantages to our ancestors had kicked in. Without my conscious involvement, my brain had, in an instant, automatically performed a safety assessment using whatever information concerning people who’d been in prisons I absorbed up to that point in my life. The problem was,having never met someone who had done a multi year prison sentence, the only information my brain had to work with was whatever I’d seen in movies, TV, documentaries, and the media. Oh boy! The more primal parts of our brains go to work even before we become consciously aware of things, and they aren’t sophisticated enough to discern the difference between reasonably reliable information and total fictions. As a result, mine had created a stereotype of “these types of men” that it felt was accurate enough to sound the prophylactic alarms (generating feelings of anxiety). This was not the mental and emotional energy I wanted the men to encounter when I met them. My dream was for them to have the happy surprise of meeting someone who was open-minded, respectful, and had no pre-existing prejudices. But back then, I just criticized myself for not being a very good practitioner of what I was trying to teach.

“To view another through the lens of the stereotypes, activated emotions, or moralistic appraisals is like putting on glasses whose prescription is designed to help you find the evidence that confirms your prejudicial views”

In the practice of NVC stereotypes, preconceptions, and any other ways that we formulate or work from assumptions about the “type” of person another is are barriers. They make it much more difficult to practice the “in-to-me-see” part of NVC, which is its heart, and where its power to calm conflict and facilitate mutually beneficial relationships comes from.

To view another through the lens of the stereotypes, activated emotions, or moralistic appraisals is like putting on glasses whose prescription is designed to help you find the evidence that confirms your prejudicial views and the emotions offered up by your primal brain to try and keep you safe. Good luck creating mutually enriching connections wearing those glasses.

Yet, given how automated the creation of this prejudice is, what can we do? I don’t know how to stop my brain from doing what it is designed to do, but I have discovered that I can stay alert to the possibility that it may happen. When it does, I remind myself that the stereotype and whatever emotions accompany it are simply the products of well intended but unsophisticated parts of my brain. Sustaining this perspective enables me to relate to those most likely incorrect phantasms my mind has produced in a detached, observing, kind of way. “There’s nothing to necessarily believe here.”, I say, “You can move on.” Doing this greatly helps me to proceed along the path I’d prefer to follow, which is to learn from the person in front of me who they actually are.

In my next instalment, I will return to the story of my night at the community clinic with the six men who were ex-prisoners. I will share how I handled a difficult moment then, and how I would handle that moment now with the deeper, more mature understanding of NVC I have 15 years later.

Wayland Myers, Ph.D. is a psychologist who writes books and articles on Nonviolent Communication and other applications of compassion. He was introduced to the Nonviolent Communication process in 1986 by its creator Dr. Marshall Rosenberg, and has since used it extensively in his personal and professional lives with profound and deeply valued results.

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - April 24, 2015

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”