The New Painting

Guillaume Apollinaire September 17, 2024

The new painters have been sharply criticized for their preoccupation with geometry. And yet, geometric figures are the essence of draftsmanship. Geometry, the science that deals with space, its measurement and relationships, has always been the most basic rule of painting.

Jost Amman, Wenzel Jamnitzer. 16th Century.

Guillaume Apollinaire, September 17th, 2024

Guillaume Apollinaire was a poet, playwright, novelist, and art critic who inspired and was admired by the Cubists and Surrealists, movements that he himself coined the terms for. Here, he writes in strong defence of Cubism against the public disdain, and shows how despite the modernity of their style, they are applying ancient laws and ideas that grounds them in tradition. He draws a comparison between Euclidian Geometry and Cubism first in a series of lectures in 1911 and then put them into words here, in 1912.

The new painters have been sharply criticized for their preoccupation with geometry. And yet, geometric figures are the essence of draftsmanship. Geometry, the science that deals with space, its measurement and relationships, has always been the most basic rule of painting.

Until now, the three dimensions of Euclidean geometry sufficed to still the anxiety provoked in the souls of great artists by a sense of the infinite – anxiety that cannot be called scientific, since art and science are two separate domains.

The new painters do not intend to become geometricians, any more than their predecessors did. But it may be said that geometry is to the plastic arts what grammar is to the art of writing. Now today's scientists have gone beyond the three dimensions of Euclidean geometry. Painters have, therefore, very naturally been led to a preoccupation with those new dimensions of space that are collectively designated, in the language of modern studios, by the term fourth dimension.

Without entering into mathematical explanations pertaining to another field, and confining myself to plastic representation as I see it, I would say that in the plastic arts the fourth dimension is generated by the three known dimensions: it represents the immensity of space eternalized in all directions at a given moment. It is space itself, or the dimension of infinity; it is what gives objects plasticity. It gives them their just proportion in a given work, where as in Greek art, for example, a kind of mechanical rhythm is constantly destroying proportion.

Greek art had a purely human conception of beauty. It took man as the measure of perfection. The art of the new painters takes the infinite universe as its ideal, and it is to the fourth dimension alone that we owe this new measure of perfection that allows the artist to give objects the proportions appropriate to the degree of plasticity he wishes them to attain.

Wishing to attain the proportions of the ideal and not limiting themselves to humanity, the young painters offer us works that are more cerebral than sensual. They are moving further and further away from the old art of optical illusion and literal proportions, in order to express the grandeur of metaphysical forms.

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) was a poet, playwright, novelist and art critic.

Ten of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 14, 2024

The Ten of Wands is the bitter end of Fire’s descent from Heaven. It has fallen from the spiritual heights it thrives in down to the material world. This is a card of weight, labor, and responsibilities that crush the spirit…

Name: Oppression, the Ten of Wands

Number: 10

Astrology: Saturn in Sagittarius

Qabalah: Malkuth of Yod

Chris Gabriel September 14, 2024

The Ten of Wands is the bitter end of Fire’s descent from Heaven. It has fallen from the spiritual heights it thrives in down to the material world. This is a card of weight, labor, and responsibilities that crush the spirit.

In Rider, we find a man bearing ten large wands, he is bending under the weight of his heavy load. In the distance we see a town, his destination still far off.

In Thoth, two leaden wands crush the eight light blue wands beneath them. It is oppression, Saturn in Sagittarius. As with the Five of Wands, Saturn is smothering the freedom of the fire which is escaping out the sides. This is especially pronounced here, as Sagittarius demands freedom of movement. The two lead wands are modified Eastern Phurbas, ritual dagger-staffs.

In Marseille, we find a similar configuration to Thoth, though the two vertical wands are beneath the crosshatched eight. Flowers are sprouting from the sides, life from the deadened, crystallized fires. As a ten, this card symbolizes Malkuth, the Kingdom, and being Wands, it belongs to the King. Thus it is the King’s Kingdom.

This card is the material reality of hierarchical power where the lofty philosophies and justifications behind oppressive regimes and states rest on the oppression of their people. While the Five of Wands showed us a tyrannical king causing strife in his court, this card is the oppressed peasantry who live under them.

The image that arises is that of the Fasci, a bundle of sticks that are weak on their own but strong together. An ancient Roman symbol taken up by many governments throughout history, but most significantly by Mussolini and his Fascist government. The ideal of strength through unity is one thing, but the question of who is to carry that heavy bundle is another. Saturn is the oppressive state, and Sagittarius is the people. They are anathema. Sagittarius needs to move freely, and Saturn needs to restrict and stabilize to maintain its power. Revolt is inevitable.

Materially, we can see this as a fire being smothered, whether this is at the onset when one adds too much wood to a tiny fire and chokes it of oxygen, or when a fire is raging and one covers it to kill it.

This is certainly not a comfortable card. When it comes up in a reading it can indicate serious pressures, smothering responsibilities, and exhaustion. This is a card of labor, hard work. Rider shows that the destination is in view, that the toils have a clear end, but there is no such promise in Marseille and Thoth, the oppression is simply there, dull and stupid work that must be done.

We can counter this by keeping the inner fire burning and finding outlets where it can run free.

Rediscovering Living Time

Tuukka Toivonen September 12, 2024

Amid our species' many disagreements, the steady progression of time seems to be the one thing that everyone can agree upon and hold in common. The ticking of the clock offers a comforting backbeat to our daily comings and goings, promoting synchrony and order where there might otherwise be disorganization or chaos. Our eagerness to keep track of the passing of minutes and hours — as much through casual glances at our screens and other timepieces as intentional planning — is unmatched in its frequency by almost any other habit...

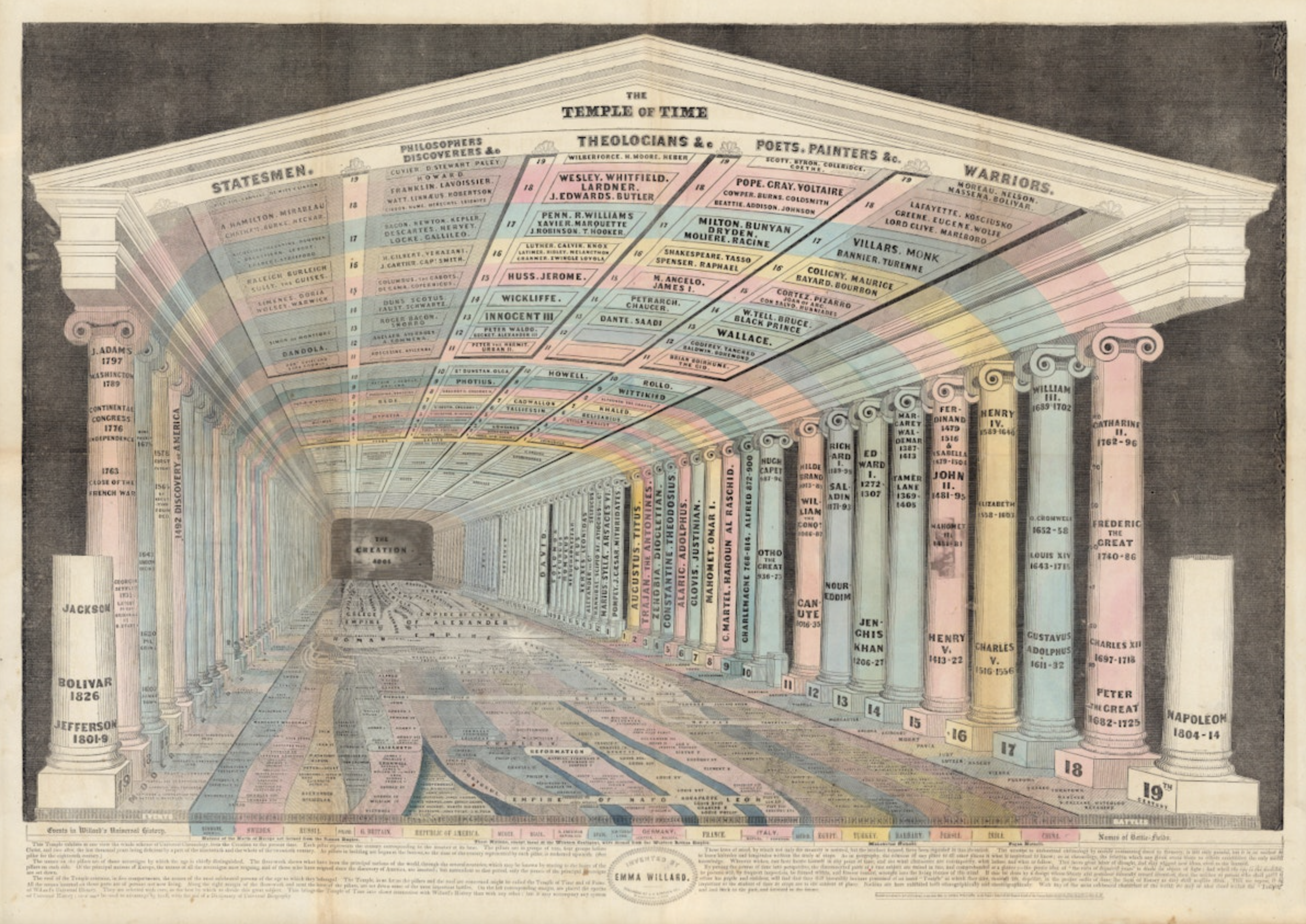

“The Temple of Time” (1846). Emma Willard.

Tuukka Toivonen September 12, 2024

Amid our species' many disagreements, the steady progression of time seems to be the one thing that everyone can agree upon and hold in common. The ticking of the clock offers a comforting backbeat to our daily comings and goings, promoting synchrony and order where there might otherwise be disorganization or chaos. Our eagerness to keep track of the passing of minutes and hours — as much through casual glances at our screens and other timepieces as intentional planning — is unmatched in its frequency by almost any other habit. There might be few moments quite as jarring as realizing one’s favored timekeeper has ground to a halt, threatening the sense of normalcy and soothing constancy afforded by clock time that our existential security seems to almost entirely rest upon. Less disorientating yet equally puzzling are the moments of flow when we become totally engrossed in soloing on the guitar, conversing with a friend or scaling up the side of a mountain, causing time as we know it to all but vanish.

Yet it is precisely these kinds of — often subtle — ruptures in one’s temporal experience that opens the door to alternative perceptions of time that can ultimately enrich our lives. Such anomalies invite active curiosity about the many mysteries and unknowns of time. Does it really progress as constantly or exist as abstractly as our attachment to machinic clock time has taught us to believe? Is time as much a co-production and outcome of life itself as it is a pace-setter? And could it be that there are cycles and makers of time that our preoccupation with the apparent precision and linearity of clock time serves to conceal? How would our lives and the way in which we partake in the more-than-human world change and expand if we explored other dimensions of time more perceptively and sensorially?

For many of us, being whisked away to a new time zone presents a type of experience that tends to fracture our sense of temporal reality quite radically — one that speaks directly to the question of how (re-)adjustment to time unfolds. We tend to normalize the sense of temporal shock by quickly adjusting our clocks to local time as soon as (or even before) we land, or by having our digital timepieces automatically adjusted for us. But our jetlagged bodies and biorhythms are not so easily persuaded, and the result is a physiological and mental sense of disorientation and fatigue at inconvenient moments. What we may not realize, however, is that the symptoms of jetlag emanate from a desynchrony of the multiple cycles we depend upon for digestion, body temperature regulation, different modes of thought, wakefulness and rest. It is therefore not the case that our acclimatization depends purely on our intentional efforts to wrestle with drowsiness — rather, it is that the complex rhythms that constitute us and the numerous symbionts we host (billions of gut microbes included) all must find a way to re-align. Restoring our “normal” sense of time and wellbeing hinges upon invisible processes through which multiple interdependent instruments — the living orchestrations of which comprise us — reach an adequate degree of synchrony and dialogue. What makes this process of readjustment truly astonishing is how it unfolds as an integrated collaboration between the vast intricacies of our biological bodies, our new environments and the way in which our home planet rotates while orbiting the sun.

As for the question of whether time marches on as precisely and exists as abstractly as we have been led to believe, exploring heliogeophysical and ecological perspectives (often neglected amid a preoccupation with physics) can help us to see a more nuanced and potent reality. First, not only do daylight hours continue to vary as the Earth travels around the sun — necessitating bodily and societal adjustments — but it actually takes the Earth slightly more than 365 days to complete one such cycle. Likewise, one rotation of the Earth on its axis does not take exactly twenty-four hours, with the Moon, earthquakes and other occurrences causing subtle fluctuations. Though imperceptible, these variations point to profound lessons about both the nature of our universe and as our own time-keeping practices and assumptions. As the historian of chronobiology and ecological restoration Mark Hall so aptly reminds us, ours is in actuality a world where “[o]rganisms do not live their lives by a metronome” but rather one where, amid constant environmental change, circadian rhythms “require continual fine-tuning” (Hall 2019, p. 385)¹. Such re-calibrations are guided by stimuli both internal and external, encompassing our solar system, our physiology as well as our social rhythms and interactions. Paradoxically enough, these multiple time-shapers that help ground our temporal experience all turn out to be far less precise and absolute than we tend to think and far more alive and idiosyncratic thanour dominant temporal cultures would imply.

“Instead of forgetting the vibrancy of living time or abandoning it in the shadow of clock time, how might you explore, and indeed celebrate, the polyphonies and polyrhythms that constitute our world and give new meaning to how time is created?”

Ecological perspectives can further enrich our understanding of time, especially if we turn to a niche group of phenologists who observe and think about the timing of diverse plant and animal species’ life-cycles. As distant as our increasingly urban and technological lives have become from the vibrant more-than-human world, most of us still retain some attachment to seasonal changes and an appreciation for their enmeshment with natural life. We intuitively realize that the appearance of swallows and other migratory birds in the Northern Hemisphere is a sign of spring (just as their return to lands in the Southern Hemisphere is taken as a sign of spring or early summer there). The blooming of certain flowers — and the simultaneous appearance of pollinators — likewise stimulates oursense of the seasons changing. The same is true of loud choruses of cicadas becoming replaced with the chirping of crickets as summer turns into autumn in places such as Japan. What phenologists have done is to bring a systematic approach to such observations of life’s cycles and developed a more refined understanding of how the rhythms of different organisms interact. For instance, flowering timings have most probably evolved with pollinators while the leaves on the same plants seem to time their cycles in relation to the herbivores that consume them. Scholars such as Bastian and Bayliss² have also brought attention to the immense value of traditional and indigenous phenological knowledges, such as calendars attuned to highly localized patterns of plant and animal life. The beauty of such calendars — that include the Japanese shi-ju-ni-ko calendar that tracks not four but forty-two seasons — is that they help bring about a sense of integration between human communities and more-than-human ecologies.

“Picture of Nations; or Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire”, (1836). Emma Willard.

In my mind, the most profound contribution of phenologists is that they show how time and its experience can be seen as collaboratively, organically constructed by multiple species, through sequences of events, interactions and degrees of synchrony. Here, the ebb and flow of life itself, its subtle orchestrations and movements, are the master time-keeper. Our mechanical timepieces and digital devices suddenly seem to offer only a vague and incomplete assessment of ‘what time it is’. Such an ecological, alternative conception of time has the power to ground our experience once again in the living world, pointing to novel possibilities for co-existence, regeneration and planetary awareness.

When we start unraveling the layers and beliefs that shape our own relationship to time, we begin to notice how entrenched notions of temporality — often linked to a need to feel productive and to conform, minute by minute, to the strictures of linear time — conceal not just how our bodies adapt to temporal disruptions and planetary movements, but an entire world of multiple times and modes of co-existence. I would now like to invite you to take a moment to reflect on how you might approach time as something that is plural, co-shaped and profoundly alive — in other words, as living time. Instead of forgetting the vibrancy of living time or abandoning it in the shadow of clock time, how might you explore, and indeed celebrate, the polyphonies and polyrhythms that constitute our world and give new meaning to how time is created? Is it possible that such an active, practical re-envisioning of time could eventually help bring more flourishing to all of the Earth’s inhabitants?

Let me leave you with a short passage from the ecological anthropologist Anna Tsing’s remarkable book, The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015), reflecting on how a full recognition of living time might allow us to generate exactly the kind of curiosity that our times require:

“Progress is a forward march, drawing other kinds of time into its rhythms. Without that driving beat, we might notice other temporal patterns. Each living thing remakes the world through seasonal pulses of growth, lifetime reproductive patterns, and geographies of expansion. Within a given species, too, there are multiple time-making projects, as organisms enlist each other and coordinate in making landscapes. The curiosity I advocate follows such multiple temporalities, revitalizing description and imagination”. (Anna Tsing 2015, p. 21.)

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.

¹ Hall, M. (2019). Chronophilia; or, Biding Time in a Solar System. Environmental Humanities, 11(2), 373–401. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-7754523

² Bastian, M., & Bayliss Hawitt, R. (2023). Multi-species, ecological and climate change temporalities: Opening a dialogue with phenology. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 6(2), 1074–1097. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486221111784

The Hermit (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 7, 2024

An old man stands with staff in one hand and a raised lantern in the other. He is lighting the dark path ahead. This is a card of hidden potential, vision, and the isolation that is necessary to realize greatness.

Name: The Hermit

Number: IX

Astrology: Virgo

Qabalah: Yod י

Chris Gabriel September 7, 2024

An old man stands with staff in one hand and a raised lantern in the other. He is lighting the dark path ahead. This is a card of hidden potential, vision, and the isolation that is necessary to realize greatness.

In Marseille, we find a wrinkled old man, with a long gray beard and hair. He holds a red staff and his lantern holds a red flame.

In Rider, we find a cloaked old man looking down, also donning a big gray beard. He raises up a lantern that contains a small star.

In Thoth, we have a more complex image, the Hermit here is not visibly human. He carries a geometric lantern with a little Sun and is surrounded by wheat. Before him is a serpent entwined egg, while Cerberus the three headed hell hound is at his feet, and along his leg, crawls a sperm in the style of Hartsoeker.

The Hermit is Virgo, and like the Lovers of Gemini, it is a sign ruled by Mercury. Both signs embody aspects of Mercury the God. Gemini is Mercurius Duplex and Virgo is the disguised Mercury from the Greek flood myth: Hermes the Hermit. Mercury, like Odin, dons a disguise when he needs to learn from the Earth. As Mercurius Duplex he comes to represent the unification of opposites like spirit and matter, masculine and feminine, life and death.

The hermit deals in seeds and seeding and, in this way, he is a magician. His letter Yod is a hand and the seed of all other letters.

The letter Yod is the seed of all other letters.

Hartsoeker's vision of sperm.

Seeds are potential, within each seed is the promise of an actualized plant. Within sperm, the human seed, is the potential for a human being. The Sperm in Thoth is a recreation of Nicolaas Hartsoeker’s vision of sperm as literally containing a microscopic human.

Just as a good farmer knows when to plant his seeds, the Hermit knows when to seed an idea, a symbol, a spell, or a word. Proper timing and placement is key. This is where the downtrodden gaze in Rider, and the Cerberus in Thoth come into play. The seeds of a Magician are not planted in soil but in the dark underground, in Hades, the Unconscious.

Alejandro Jodorowsky relates the Hermit’s number 9 to the nine months of pregnancy. The seed is buried and spends its allotted time in the dark and fertile womb.

Sometimes we need to spend time in isolation, in hermitude to be born again, to fertilize our own ideas and dreams.

The Hermit also differs from the Lovers in that the Lovers relates to copulation, while the Hermit is related to masturbation. Hermes was said to have invented masturbation, and his hermit disciples were said to worship him by masturbating. Chaos Magicians believe masturbating to the image or idea of a symbol plants it in the Unconscious.

Consider the idiom ‘sow the seed’; sowing seeds of decay, distrust, love etc. Ideas are the seeds that Mercury is most interested in. A well placed word or expression can drastically alter reality, it can save lives or end them by its utterance.

The Hermit sees the potential in all of these: ideas, seeds, and sperm. All of these that tend to be carelessly discarded are the very stuff of miracles in the hands of one who deals in potentials. He takes them up in his lantern and lights a path in the darkness of the undecided future.

When pulling this card, we may be faced with a period of boredom and isolation. This can be wasted and suffered through, or it can be a time of growth and development. We can be a seed that grows while hidden, or lay fallow. The choice is ours.

Simple Expression of the Complex Thought

Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman September 4, 2024

In his column in The New York Times, the art critic Edgar Allen Jewell wrote a review of a new show hosted by the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. He expressed his befuddlement at this distinctly modern art, devoid of figuration or tangible form, singling out the work of Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb. Yet, in an unusual act of humble awareness, he offered up the inches of his column to these same artists if they cared offer a response...

Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis. 1950-51.

Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman September 4th, 2024

In his column in The New York Times, the art critic Edgar Allen Jewell wrote a review of a new show hosted by the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. He expressed his befuddlement at this distinctly modern art, devoid of figuration or tangible form, singling out the work of Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb. Yet, in an unusual act of humble awareness, he offered up the inches of his column to these same artists if they cared offer a response. It was Barnett Newman, who had shown in the same exhibition but not been spotlighted by Jewell, who Rothko and Gottlieb came to with this offer, and Newman penned the following work that the two others signed their name to in agreement. The following essay served as a sort of defacto manifesto for this new form of American painting they were creating – a neo-expressionist style interested in myths, symbols, and emotions above all else. It first appeared in Jewell’s column in June of 1943.

To the artist the workings of the critical mind is one of life's mysteries. That is why, we suppose, the artist's complaint that he is misunderstood, especially by the critic, has become a noisy commonplace. It is therefore an event when the worm turns and the critic quietly, yet publicly, confesses his 'befuddlement,' that he is 'nonplused' before our pictures at the federation show. We salute this honest, we might say cordial, reaction toward our 'obscure' paintings, for in other critical quarters we seem to have created a bedlam of hysteria. And we appreciate the gracious opportunity that is being offered us to present our views.

We do not intend to defend our pictures. They make their own defense. We consider them clear statements. Your failure to dismiss or disparage them is prima facie evidence that they carry some communicative power. We refuse to defend them not because we cannot. It is an easy matter to explain to the befuddled that The Rape of Persephone is a poetic expression of the essence of the myth; the presentation of the concept of seed and its earth with all the brutal implications; the impact of elemental truth. Would you have us present this abstract concept, with all its complicated feelings, by means of a boy and girl lightly tripping?

It is just as easy to explain The Syrian Bull as a new interpretation of an archaic image, involving unprecedented distortions. Since art is timeless, the significant rendition of a symbol, no matter how archaic, has as full validity today as the archaic symbol had then. Or is the one 3000 years old truer? ...easy program notes can help only the simple-minded.

No possible set of notes can explain our paintings. Their explanation must come out of a consummated experience between picture and onlooker. The point at issue, it seems to us, is not an 'explanation' of the paintings, but whether the intrinsic ideas carried within the frames of these pictures have significance. We feel that our pictures demonstrate our aesthetic beliefs, some of which we, therefore, list:

Adolph Gottlieb, The Rape of Persephone. 1943.

1. To us art is an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by those willing to take the risks.

2. This world of the imagination is fancy-free and violently opposed to common sense.

3. It is our function as artists to make the spectator see the world our way - not his way.

4. We favor the simple expression of the complex thought. We are for the large shape because it has the impact of the unequivocal. We wish to reassert the picture plane. We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.

5. It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academism. There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject-matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.

Consequently, if our work embodies these beliefs it must insult any one who is spiritually attuned to interior decoration; pictures for the home; pictures for over the mantel; pictures of the American scene; social pictures; purity in art; prize-winning potboilers; the National Academy, the Whitney Academy, the Corn Belt Academy; buckeyes; trite tripe, etc.

Adolph Gottlieb (1903-1974), Mark Rothko (1903-1970), and Barnett Newman (1095-1970) were American Abstract Artists who together created a new visual language built on symbols, mythology, and color.

The Guldara Stupa (Artefact V)

Ben Timberlake September 3, 2024

The Guldara Stupa is one of the most beautiful Buddhist ruins in Afghanistan. It sits at the head of a valley on a proud spur of rock. Behind it is the remains of the adjoining monastery. The stupa is comprised of a square base with two concentric drums above it. Atop them, a dome, partially shattered and missing its spire...

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 5

Description: Guldara Stupa

Location: Logar Province, Afghanistan

Age: 2000 Years Old

Ben Timberlake September 3, 2024

The Guldara Stupa is one of the most beautiful Buddhist ruins in Afghanistan. It sits at the head of a valley on a proud spur of rock. Behind it is the remains of the adjoining monastery. The stupa is comprised of a square base with two concentric drums above it. Atop them, a dome, partially shattered and missing its spire.

The role of a stupa has been described as ‘an engine for salvation, a spiritual lighthouse, a source of the higher, ineffable illumination that brought enlightenment’¹. The design is thought to have evolved from earlier conical burial mounds on circular bases that were being built in the century before the birth of the Buddha, from the Mediterranean all the way down to the Ganges Valley. According to early Buddhist texts, Buddha himself demonstrated to his followers how to build the first stupa by folding his cloak into a square as a base, then putting his alms bowl upside-down and on top of the cloak, with his staff on top of that to represent the spire.

Ancient sculpture of the Buddha alongside a corinthian column.

The Guldara Stupa, whose name translates to ‘stupa of the flower valley,’ is the best surviving example of the sophisticated architectural developments during the Kushan period. This Empire, which flourished from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE, epitomized the cultural exchange and fusion between East and West along the Silk Road. Originally nomads from Central Asia, Kushans created a vast kingdom spanning parts of modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India. They adeptly blended elements from Greek, Roman, Persian, and Indian traditions to create a unique syncretic culture. This melding and harmonization was evident in their art, and particularly in the Gandharan style, which combined Hellenistic techniques with Buddhist themes. A Greek influence entered with Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BC and continued through subsequent Hellenistic kingdoms. Prior to this the Buddha was represented symbolically, but the Greeks introduced more human representations of the Buddha: realistic proportions, naturalistic facial features, and the contrapposto stance. Many Gandharan Buddhas appear in Greek-style clothing with wavy hair and long noses set on oval faces, typical of classical sculpture. In the sculpture here he appears sat at a banquet beside a corinthian column.

“In a single structure, philosophies and ideas from thousands of miles over converge in perfect harmony.”

The Kushans were also instrumental in the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road, patronizing Buddhist art and architecture while maintaining a religiously tolerant empire. Their capitals, like Bagram, became cosmopolitan centers where goods and ideas from China, India, and the Mediterranean world converged. Their coinage featured Greek inscriptions alongside Indian languages, and depicted both Greek and Indian deities. In governance, they adopted titles from various traditions, such as "King of Kings" (Shah-in Shah), reflecting Persian influence. This Kushan synthesis not only shaped the cultural landscape of Central and South Asia but also facilitated the transmission of ideas and technologies between East and West, leaving a lasting legacy that extended far beyond their political boundaries.

Corinthian pilasters with their Corinthian capitals.

The Guldara Stupa reflects this assimilation. The core structure is a classic stupa design that served both symbolic and practical functions in Buddhist practice. Its form represents cosmic order and the path to enlightenment, while its circular base allows for circumambulation (pradakshina), a key ritual in Buddhist worship. Yet the harmonious proportions of the square base are similar to the Temple of Hera on Samos and the engaged pilasters,with their corinthian capitals, are almost pure classical world finished in flaked local schist. In a single structure, philosophies and ideas from thousands of miles over converge in perfect harmony.

The decline of Buddhism in Afghanistan was not a sudden event but a gradual process that occurred over several centuries. While Buddhism flourished in the region from the 1st to 7th centuries CE, its influence began to wane with the spread of Islam from the west starting in the 7th century. Archaeological evidence, however, suggests that Buddhist practices persisted in some areas long after the initial Muslim conquests. The transition was not uniformly abrupt or violent, as sometimes portrayed in later folklore. Instead, there was a period of coexistence, with some Buddhist sites remaining active even as Islam gained prominence. The process of conversion was complex, influenced by political, economic, and social factors. By the 11th century, Islam had become the predominant faith in the Kabul region and most of Afghanistan, though pockets of Buddhist practice may have survived in remote areas.

The abandonment of many Buddhist sites was likely due to a combination of factors, including changing patronage patterns, shifts in trade routes, and the gradual adoption of Islam by the local population. Interestingly, some Buddhist architectural and artistic elements were incorporated into early Islamic structures in the region, reflecting a degree of cultural continuity amid religious change. The last definitive evidence of active Buddhist practice in Afghanistan dates to around the 10th century, marking the end of a remarkable era of religious and cultural flourishing that had lasted for nearly a millennium.

Ben Timberlake at the Guldara Stupa.

It was Guldara’s remote position that probably accounts for its remarkable preservation. In the 19th century it was looted by the British explorer and archaeologist Charles Masson. (It’s a little mean to use the word ‘looted’: he ‘opened’ the stupa looking for relics and artifacts as was the practice at the time). Masson was a fascinating character. His actual name was James Lewis but he deserted from the East India Company’s army in 1827 and adopted the alias Charles Masson. He spent much of the 1830s living in Kabul, travelling the country extensively and documenting the Buddhist archaeological sites there. His work was crucial in bringing these sites the attention of Western scholars. Guldara was his favourite, “perhaps the most complete and beautiful monument of the kind in these countries’.

I visited Guldara this July. It is an hour’s drive from Kabul to the village at the head of the valley, then another 20 minutes up the dry riverbed that tested our 4x4, and finally a half an hour’s trek up to the site itself. There is something deeply spiritual about the Stupa. It seems to belong profoundly to the place - to the valley - and yet floats above it. Its lines and proportions are as graceful as the surrounding mountains while its myriad of eastern and western architectural forms have integrated to be more than the sum of their parts. It is a site of quiet conjunction, of perfect harmony. Of peace.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

¹ The Buddhas of Bamiya, Llewelyn Morgan.

The Queen of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 31, 2024

The Queen of Wands is a court card, and the second highest in the suit of Wands. In each iteration we find our Queen, enrobed, crowned, and bearing a Wand. This is a card of aggression and desire...

Name: Queen of Wands

Astrology: Aries, Water of Fire

Qabalah: He ה of Yod י

Chris Gabriel August 31, 2024

The Queen of Wands is a court card, and the second highest in the suit of Wands. In each iteration we find our Queen, enrobed, crowned, and bearing a Wand. This is a card of aggression and desire.

In Marseille, we find the Queen looking down, her golden wand’s base in her lap, a symbolic phallus. Her long hair and robes flow about her. Both of her hands are at her waist.

In Rider, we find the Queen on a throne adorned with lions. Her right hand bears her wands and her left a Sunflower. Below her stage sits a little black cat. She is a young woman with a demure gaze.

In Thoth, we find the Queen inflamed. Her hair is made of fire that give way to the flames all around her. She looks directly down. Her crown is topped by a hawk, and her wand by a pinecone. She is petting a cheetah.

The Queen of Wands is a card of duality - fire and water, aggression and love, innocence and experience.

A phrase that comes to mind is “Cute Aggression”, the urge to squeeze and bite cute things without actually wanting to cause harm. It’s a confusion of two drives, maternal love and aggression. This is the nature of the Queen of Wands, the struggle between these drives.

Aries is the first sign and known as the “baby of the zodiac”, it is just learning how to exist. Kittens bite and scratch, without any malice, in acts of innocent violence: this is the domain of the Queen of Wands. Animal aggression can be read as the Saturnian child devouring drive, or as the innocent violence of Aries. One wants to maintain power, while the other is trying to gain power.

This follows with the twin of violence, sex. The development of sexuality through aggression, which appears as teasing and name-calling, is opposed to the aggression that expresses itself sexually.

This is the domain of the Queen of Wands who balances these things in her hands, the wand and the flower, the masculine and the feminine, the phallus and yoni.

This card often can indicate a person, often an Aries, but generally a very dominant woman unafraid to express her opinions.The card is the elemental inverse of the Knight of Cups, who balances water and fire, but chooses confused chastity that keeps his heart pure at the cost of his aggressive will, whereas the Queen of Wands takes on the far more difficult task of approaching the world willfully while fighting to keep her heart pure.

When we pull this card, we are often met with this same dilemma, the balancing of love and will. The Queen is telling us “And whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not unto men;”

Towards Alienation

Arcadia Molinas August 29, 2024

Engaging in an uncomfortable reading practice, favouring ‘foreignization’, has the potential to expand our subjectivities and lead us to embrace the cultural other instead of rejecting it. In this walk away from fluency, we find ourselves heading towards alienation. But what does it mean to be alienated as a reader, how does it feel, and perhaps most importantly, how does it happen?

Interessenspharen, 1979. Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt.

Arcadia Molinas August 29, 2024

Last time, translator Lawrence Venuti and philosopher Friedreich Schleirmacher showed us the radical potential of walking away from fluency when reading books in translation. Engaging in an uncomfortable reading practice, they argued, favouring ‘foreignization’, has the potential to expand our subjectivities and lead us to embrace the cultural other instead of rejecting it. In this walk away from fluency, we find ourselves heading towards alienation. But what does it mean to be alienated as a reader, how does it feel, and perhaps most importantly, how does it happen?

The concept of culturemes can help us get closer to an understanding of alienation. Culturemes are social phenomena that have meaning to members of one culture but not to another, so that when they are compared to a corresponding phenomenon in another culture, they are revealed to be specific to only the first culture. They can have an ingrained historical, social or geographical relevance that can result in misconceptions or misunderstandings when being translated. This includes jokes, folklore, idioms, religion or expressions. If we pay attention to the translation of culturemes, we can evaluate how alienation is functioning in the translated text and sketch the contours of its effect on the reader.

Panza de Burro by Andrea Abreu made my body come alive from just one sitting. Even in its original Spanish, the book is alienating. Abreu takes us into the mind of her ten-year old narrator, nicknamed “Shit”, as she spends a warm, cloudy summer in a working-class neighbourhood of Tenerife with her best friend Isora. The language is mercilessly juvenile, deliciously phonetic and profoundly Canarian. The Canarian accent, more like the Venezuelan or Cuban accents of Latin America than a mainland Spanish accent, is emulated in a way similar to what Irvine Welsh does for the Scots dialect in Trainspotting. This means, for example, that a lot of the ends of words are cut off, “usted” becomes “usté”, “nada más” becomes “namás”. On top of this are all the Canarian idiosyncrasies that Abreu employs to paint a vivid sense of place: the food, the weather, the games the children play. Abreu demands her reader move towards her characters, their language, their codes and their culture and with it demands a somatic response from her reader. The translation of such a book should be a fertile ground for the experience of alienation, done two-fold.

“Meeting halfway is a political act that not only allows people to exist at the frontier but brings everyone closer to the frontier too.”

Widening, 1980. Ruth Wolf-Rehfeltd.

On the first page of Panza de Burro, Shit and Isora are eating snacks and sweets at a birthday party, “munchitos, risketos, gusanitos, conguitos, cubanitos, sangüi, rosquetitos de limón, suspiritos, fanta, clipper, sevená, juguito piña, juguito manzana”. Most of these will be familiar to anyone who has grown up in Spain, including the intentional spelling mistakes (“sevená” for example is meant to emulate the Canarian pronunciation of 7-Up). Julia Sanches, in her translation, Dogs of Summer, writes “There were munchitos potato chips, cheese doodles and Gusanitos cheese puffs. There were Conguitos chocolate sweets, cubanitos wafers and sarnies. There were lemon donuts and tiny meringues, orange Fanta, strawberry pop, 7-Up, apple juice and pineapple juice”. The alienating words are still present in the translation, munchitos, gusanitos, conguitos, their rhythm, their sound, carry an echo of their cultural significance and with them maintain the sticky, childish essence of the Canarian birthday party. They are there to flood your senses, which is what, at its best, alienation can hope to do. Yet the words themselves, the look of them, the sound of them, could have also done their infantilizing, somatic job of taking us into the soda pop-flavoured heart of the birthday party taking place on a muggy Canarian day without their tagging English accompaniment “cheese puffs”. To be able to chew the words around for yourself is essential to experience alienation. To experience the foreign, your mouth must move in ways and shapes hitherto unfamiliar to it. In other instances, however, Sanches keeps Canarian culturemes intact, for example the term of endearment “miniña” is untouched in the translated text, which again with its heavily onomatopoeic sound thrusts the unfamiliar reader into a new context, this time for endearment, and so expands the sounds and shapes of affection and proximity.

Gloria Anzaldúa, feminist and queer scholar, wrote Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, a book which takes the alienating project to its logical extreme. The book is not only an exercise in alienation through language but in alienation through form too. Drawing inspiration from her Chicana identity, an identity inherently at a crossroads between Mexicana and tejana cultures, she advocates for a wider “borderlands culture”, a culture that can represent and hold space for the in-between, the interdisciplinary and the intercontinental. In the preface she explains her project, “The switching of "codes" in this book from English to Castilian Spanish to the North Mexican dialect to Tex-Mex to a sprinkling of Nahuatl to a mixture of all of these, reflects my language, a new language-the language of the Borderlands. There, at the juncture of cultures, languages cross-pollinate and are revitalized; they die and are born. Presently this infant language... this bastard language, Chicano Spanish, is not approved by any society. But we Chicanos no longer feel that we need to beg entrance, that we need always to make the first overture –to translate to Anglos, Mexicans and Latinos, apology blurting out of our mouths with every step. Today we ask to be met halfway. This book is our invitation to you-from the new mestizas.”

Anzaldúa wrote a guide on how to live on the borderlands, how to embrace linguistic and cultural hybridity, supporting Venuti and Schleirmacher’s claim that a wider acceptance of difference, of meeting halfway, is a political act that not only allows people to exist at the frontier, but brings everyone closer to the frontier too. Being on the frontier means going towards alienation, it means offering your body to new expressions and new experiences, it is to remain open, to walk on the border like a tightrope, to feel the tension in your muscles from the balance and to come out taught at the other end.

Arcadia Molinas is a writer, editor, and translator from Madrid. She currently works as the online editor of Worms Magazine and has published a Spanish translation of Virginia Woolf’s diaries with Funambulista.

Music Lover’s Field Companion

John Cage August 27, 2024

I have come to the conclusion that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom. For this purpose I have recently moved to the country. Much of my time is spent poring over "field companions on fungi. These I obtain at half price in second-hand bookshops, which latter are in some rare cases next door to shops selling dog-eared sheets of music, such an occurrence being greeted by me as irrefutable evidence that I am on the right track...

Artwork by Lois Long, for John Cage’s 'Mushroom Book' 1972.

John Cage August 27 2024

I have come to the conclusion that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom. For this purpose I have recently moved to the country. Much of my time is spent poring over "field companions on fungi. These I obtain at half price in second-hand bookshops, which latter are in some rare cases next door to shops selling dog-eared sheets of music, such an occurrence being greeted by me as irrefutable evidence that I am on the right track.

The winter for mushrooms, as for music, is a most sorry season. Only in caves and houses where matters of temperature and humidity, and in concert halls where matters of trusteeship and box office are under constant surveillance, do the vulgar and accepted forms thrive. American commercialism has brought about a grand deterioration of the Psalliota campestris, affecting through exports even the European market. As a demanding gourmet sees but does not purchase the marketed mushroom, so a lively musician reads from time to time the announcements of concerts and stays quietly at home. If, energetically, Collybia velutipes should fruit in January, it is a rare event, and happening on it while stalking in a forest is almost beyond one's dearest expectations, just as it is exciting in New York to note that the number of people attending a winter concert requiring the use of one's faculties is on the upswing (1954: 129 out of l2,000,000; 1955: 136 out of 12,000,000).

In the summer, matters are different. Some three thousand different mushrooms are thriving in abundance, and right and left there are Festivals of Contemporary Music. It is to be regretted, however, that the consolidation of the acquisitions of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, currently in vogue, has not produced a single new mushroom. Mycologists are aware that in the present fungous abundance, such as it is, the dangerous Amanitas play an extraordinarily large part. Should not program chairmen, and music lovers in general, come the warm months, display some prudence?

I was delighted last fall (for the effects of summer linger on, viz. Donaueschingen, C. D. M. I., etc.) not only to revisit in Paris my friend the composer Pierre Boulez, rue Beautreillis, but also to attend the Exposition du Champignon, rue de Buffon. A week later in Cologne, from my vantage point in a glass-encased control booth, I noticed an audience dozing off, throwing, as it were, caution to the winds, though present at a loud-speaker emitted program of Elektronische Musik. I could not help recalling the riveted attention accorded another loud-speaker, rue de Buffon, which delivered on the hour a lecture describing mortally poisonous mushrooms and means for their identification.

“The second movement was extremely dramatic, beginning with the sounds of a buck and a doe leaping up to within ten feet of my rocky podium. The expressivity of this movement was not only dramatic but unusually sad from my point of view, for the animals were frightened simply because I was a human being.”

John Cage and Lois Long.

But enough of the contemporary musical scene; it is well known. More important is to determine what are the problems confronting the contemporary mushroom. To begin with, I propose that it should be determined which sounds further the growth of which mushrooms; whether these latter, indeed, make sounds of their own; whether the gills of certain mushrooms are employed by appropriately small-winged insects for the production of pizzicati and the tubes of the Boleti by minute burrowing ones as wind instruments; whether the spores, which in size and shape are extraordinarily various, and in number countless, do not on dropping to the earth produce gamelan-like sonorities; and finally, whether all this enterprising activity which I suspect delicately exists, could not, through technological means, be brought, amplified and magnified, into our theatres with the net result of making our entertainments more interesting.

What a boon it would be for the recording industry (now part of America'. sixth largest) if it could be shown that the performance, while at table, of an LP of Beethoven's Quartet Opus Such-and-Such so alters the chemical nature of Amanita muscaria as to render it both digestible and delicious!

Lest I be found frivolous and light-headed and, worse, an "impurist" for having brought about the marriage of the agaric with Euterpe, observe that composers are continually mixing up music with something else. Karlheinz Stockhausen is clearly interested in music and juggling, constructing as he does "global structures," which can be of service only when tossed in the air; while my friend Pierre Boulez, as he revealed in a recent article (Nouvelle Revue Française, November 1954), is interested in music and parentheses and italics! This combination of interests seems to me excessive in number. I prefer my own choice of the mushroom. Furthermore it is avant-garde.

I have spent many pleasant hours in the woods conducting performances of my silent piece~ transcriptions, that is, for an audience of myself, since they were much longer than the popular length which I have had published. At one performance, I passed the first movement by attempting the identification of a mushroom which remained successfully unidentified. The second movement was extremely dramatic, beginning with the sounds of a buck and a doe leaping up to within ten feet of my rocky podium. The expressivity of this movement was not only dramatic but unusually sad from my point of view, for the animals were frightened simply because I was a human being. However, they left hesitatingly and fittingly within the structure of the work. The third movement was a return to the theme of the first, but with all those profound, so-well-known alterations of world feeling associated by German tradition with the A-B-A.

In the space that remains, I would like to emphasize that I am not interested in the relationships between sounds and mushrooms any more than I am in those between sounds and other sounds. These would involve an introduction of logic that is not only out of place in the world, but time consuming. We exist in a situation demanding greater earnestness, as I can testify, since recently I was hospitalized after having cooked and eaten experimentally some Spathyema foetida, commonly known as skunk cabbage. My blood pressure went down to fifty, stomach was pumped, etc. It behooves us therefore to see each thing directly as it is, be it the sound of a tin whistle or the elegant Lepiota procera.

John Cage was an American composer, writer, music theorist and amateur mycologist. He was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde and amongst the most consequential and important composers of the 20th Century.

The Emperor (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 24, 2024

The Emperor is the beginning of the Tarot’s journey through the Zodiac, and it starts, as with ‘The Canterbury Tales’, when “the yonge sonne hath in the Ram his half cours yronne”. This is a card of paternal, masculine power. In each iteration we see the Emperor crowned, enthroned, and bearing a scepter…

Name: The Emperor

Number: IV

Astrology: Aries

Qabalah: Tzaddi

Chris Gabriel August 24, 2024

The Emperor is the beginning of the Tarot’s journey through the Zodiac, and it starts, as with ‘The Canterbury Tales’, when “the yonge sonne hath in the Ram his half cours yronne”. This is a card of paternal, masculine power. In each iteration we see the Emperor crowned, enthroned, and bearing a scepter.

In Rider, we find an aged Emperor with a long white beard and a deep red cloak covering his armor. He is facing ahead. His scepter is a ‘crux ansata’, a variation on the Ankh of the Egyptians, that is a symbol of the whole of things (0, the Creative Nothing and “+” the Cross as Four elements), for this is the King of the World. In his other hand is a globe of gold. His throne has four ram heads. The background is made up of fiery mountains.

In Thoth, we find the Emperor depicted entirely with a fiery palette. He has a shorter beard, and a tunic bearing symbols of his dominion. The Bee is of particular interest here, serving as a symbol of natural hierarchy. His scepter bears the head of a ram, and his globe is in the form of Boehme’s Globus Cruciger. A shield depicting a double Phoenix lays at his feet alongside a sheep with a flag. Behind him are two large rams. Unlike the Rider Emperor, he has crossed legs, this posture, along with his arms form the Alchemical sign of Sulphur.

In Marseille, we once again find the Emperor older, with gray hair and a beard. He has a golden cross necklace, a crown that appears like fire, and a scepter bearing the Globus Cruciger. A shield bearing an eagle lays at his cross feet.

The Emperor is the card of the Good King, the good father, the righteous power in Man, not a wicked king, or an unjust ruler. This is a King Arthur, the one who is powerful by nature. The Bee in Thoth is a symbol shared with the Empress, the Lovers, and Art. Together they form an alchemical narrative, a Chymical Wedding. Bees form beautiful geometric hives, and unlike wasps, they give sweet honey. This is the ideal form of hierarchy, one that is natural and bears great fruits for all.

Explainer of Boehme’s Globus Cruciger.

As Aries is the first sign, we see the Emperor is primus inter pares, first among equals. Aries is the ‘baby of the zodiac’, and like Arthur is given rulership very early on. Aries the Ram uses his horns to force his way through, though his horns protect him, his butting head causes a tremendous shock.

This too is the nature of a King - if they are ‘Great’ in the historical sense, they are not easy on those around them. Great Kings are terrible cataclysms. The Globus Cruciger that he bears, according to the alchemist Jakob Boehme, is the image of lightning striking the world. And the yogic posture, which forms Sulphur, is an ideogram constituted by a simple stick figure crowned by fire, a fiery man.

The Emperor is like a Ram that makes sparks with each thrust of his horns, and sets himself aflame. In old stories, we like to see a young person gain the mandate of Heaven and go to war, fighting their way to the top and then wielding tough but just judgment. In our day to day lives however, this may not be the case.

As we bring the scale of this card down, we find the Father, the masculine man, and while the divine fire is in the righteous, this is a figure that can be ill dignified and, if not checked, become a tyrant, an arrogant aggressive man who believes in his own superiority.

Yogic posture ideogram.

This is where Aries' opposition to Libra comes in handy. It is what Crowley saw as “Love and Will” and, even further, the idea that Love is the Law. If the King’s law is not Love, then he is unjust, an overabundance of the aggressive Aries without the balance of Libra’s scales.

The balance of these energies makes a great King and an even greater Father. Paternal authority should be reserved entirely to keep his Kingdom, his home at peace and loving, not to tyrannize those he rules.

When the Emperor is pulled in a reading, I find it tends to relate directly to a Father, or to a position of authority. This can be someone’s literal father or a father figure, or a position they are in or want to be in. It can also simply indicate the energy of Aries.

I Am For An Art… (1961)

Claes Oldenburg August 22, 2024

I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.

I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all, an art given the chance of having a starting point of zero...

Oldenburg in The Store, 107 East Second Street, New York, 1961. Robert R. McElroy.

Claes Oldenburg August 22 2024

I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.

I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all, an art given the chance of having a starting point of zero.

I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap & still comes out on top.

I am for an art that imitates the human, that is comic, if necessary, or violent, or whatever is necessary.

I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself.

I am for an artist who vanishes, turning up in a white cap painting signs or hallways.

I am for art that comes out of a chimney like black hair and scatters in the sky.

I am for art that spills out of an old man's purse when he is bounced off a passing fender.

I am for the art out of a doggy's mouth, falling five stories from the roof.

I am for the art that a kid licks, after peeling away the wrapper. I am for an art that joggles like everyones knees, when the bus traverses an excavation.

I am for art that is smoked, like a cigarette, smells, like a pair of shoes.

I am for art that flaps like a flag, or helps blow noses, like a handkerchief.

Pastry Case, 1961. Claes Oldenburg.

I am for art that is put on and taken off, like pants, which develops holes, like socks, which is eaten, like a piece of pie, or abandoned with great contempt, like a piece of shit.

I am for art covered with bandages, I am for art that limps and rolls and runs and jumps. I am for art that comes in a can or washes up on the shore.

I am for art that coils and grunts like a wrestler. I am for art that sheds hair.

I am for art you can sit on. I am for art you can pick your nose with or stub your toes on.

I am for art from a pocket, from deep channels of the ear, from the edge of a knife, from the corners of the mouth, stuck in the eye or worn on the wrist.

I am for art under the skirts, and the art of pinching cockroaches.

I am for the art of conversation between the sidewalk and a blind mans metal stick.

I am for the art that grows in a pot, that comes down out of the skies at night, like lightning, that hides in the clouds and growls. I am for art that is flipped on and off with a switch.

I am for art that unfolds like a map, that you can squeeze, like your sweetys arm, or kiss, like a pet dog. Which expands and squeaks, like an accordion, which you can spill your dinner on, like an old tablecloth.

I am for an art that you can hammer with, stitch with, sew with, paste with, file with.

I am for an art that tells you the time of day, or where such and such a street is.

I am for an art that helps old ladies across the street.

I am for the art of the washing machine. I am for the art of a government check. I am for the art of last wars raincoat.

I am for the art that comes up in fogs from sewer-holes in winter. I am for the art that splits when you step on a frozen puddle. I am for the worms art inside the apple. I am for the art of sweat that develops between crossed legs.

I am for the art of neck-hair and caked tea-cups, for the art between the tines of restaurant forks, for the odor of boiling dishwater.

I am for the art of sailing on Sunday, and the art of red and white gasoline pumps.

I am for the art of bright blue factory columns and blinking biscuit signs.

I am for the art of cheap plaster and enamel. I am for the art of worn marble and smashed slate. I am for the art of rolling cobblestones and sliding sand. I am for the art of slag and black coal. I am for the art of dead birds.

I am for the art of scratchings in the asphalt, daubing at the walls. I am for the art of bending and kicking metal and breaking glass, and pulling at things to make them fall down.

I am for the art of punching and skinned knees and sat-on bananas. I am for the art of kids' smells. I am for the art of mama-babble.

I am for the art of bar-babble, tooth-picking, beerdrinking, egg-salting, in-suiting. I am for the art of falling off a barstool.

I am for the art of underwear and the art of taxicabs. I am for the art of ice-cream cones dropped on concrete. I am for the majestic art of dog-turds, rising like cathedrals.

I am for the blinking arts, lighting up the night. I am for art falling, splashing, wiggling, jumping, going on and off.

I am for the art of fat truck-tires and black eyes.

Performances at Oldenburg's The Store, 1962. Robert R. McElroy.

I am for Kool-art, 7-UP art, Pepsi-art, Sunshine art, 39 cents art, 15 cents art, Vatronol art, Dro-bomb art, Vam art, Menthol art, L & M art, Ex-lax art, Venida art, Heaven Hill art, Pamryl art, San-o-med art, Rx art, 9.99 art, Now art, New art, How art, Fire sale art, Last Chance art, Only art, Diamond art, Tomorrow art, Franks art, Ducks art, Meat-o-rama art.

I am for the art of bread wet by rain. I am for the rat's dance between floors.

I am for the art of flies walking on a slick pear in the electric light. I am for the art of soggy onions and firm green shoots. I am for the art of clicking among the nuts when the roaches come and go. I am for the brown sad art of rotting apples.

I am for the art of meowls and clatter of cats and for the art of their dumb electric eyes.

I am for the white art of refrigerators and their muscular openings and closings.

I am for the art of rust and mold. I am for the art of hearts, funeral hearts or sweetheart hearts, full of nougat. I am for the art of worn meathooks and singing barrels of red, white, blue and yellow meat.

I am for the art of things lost or thrown away, coming home from school. I am for the art of cock-and-ball trees and flying cows and the noise of rectangles and squares. I am for the art of crayons and weak grey pencil-lead, and grainy wash and sticky oil paint, and the art of windshield wipers and the art of the finger on a cold window, on dusty steel or in the bubbles on the sides of a bathtub.

I am for the art of teddy-bears and guns and decapitated rabbits, exploded umbrellas, raped beds, chairs with their brown bones broken, burning trees, firecracker ends, chicken bones, pigeon bones and boxes with men sleeping in them.

I am for the art of slightly rotten funeral flowers, hung bloody rabbits and wrinkly yellow chickens, bass drums & tambourines, and plastic phonographs. I am for the art of abandoned boxes, tied like pharaohs. I am for an art of watertanks and speeding clouds and flapping shades.

I am for U.S. Government Inspected Art, Grade A art, Regular Price art, Yellow Ripe art, Extra Fancy art, Ready-to-eat art, Best-for-less art, Ready-tocook art, Fully cleaned art, Spend Less art, Eat Better art, Ham art, pork art, chicken art, tomato art, banana art, apple art, turkey art, cake art, cookie art.

add:

I am for an art that is combed down, that is hung from each ear, that is laid on the lips and under the eyes, that is shaved from the legs, that is brushed on the teeth, that is fixed on the thighs, that is slipped on the foot.

square which becomes blobby

Claes Oldenburg, 1929 – 2022, was a Swedish-born American sculptor best known for his public art installations, typically featuring large replicas of everyday objects. In 1961 he opened The Store in Downtown New York which hosted performances, conceptual art pieces and happenings, as well as selling work he made in the space to punters and passerbys, removing the middle-man from the commercialisation of the art world. He wrote this text for an exhibition catalogue in 1961, reworked it when he opened the store and then republished it again in 1970 for an exhibition in London, from which this version is taken.

Mystery and Creation (1928)

Giorgio de Chirico August 20, 2024

To become truly immortal a work of art must escape all human limits: logic and common sense will only interfere. But once these barriers are broken it will enter the regions of childhood vision and dream.

Piazza D'Italia, 1964. Giorgio de Chirico.

Giorgio de Chirico August 20 2024

To become truly immortal a work of art must escape all human limits: logic and common sense will only interfere. But once these barriers are broken it will enter the regions of childhood vision and dream.

Profound statements must be drawn by the artist from the most secret recesses of his being; there no murmuring torrent, no birdsong, no rustle of leaves can distract him.

What I hear is valueless; only what I see is living, and when I close my eyes my vision is even more powerful. It is most important that we should rid art of all that it has contained of recognizable material to date, all familiar subject matter, all traditional ideas, all popular symbols must be banished forthwith. More important still, we must hold enormous faith in ourselves: it is essential that the revelation we receive, the conception of an image which embraces a certain thing, which has no sense in itself, which has no subject, which means absolutely nothing from the logical point of view, I repeat, it is essential that such a revelation or conception should speak so strongly in us, evoke such agony or joy, that we feel compelled to paint, compelled by an impulse even more urgent than the hungry desperation which drives a man to tearing at a piece of bread like a savage beast.

I remember one vivid winter's day at Versailles. Silence and calm reigned supreme. Everything gazed at me with mysterious, questioning eyes. And then I realized that every corner of the palace, every column, every window possessed a spirit, an impenetrable soul. I looked around at the marble heroes, motionless in the lucid air, beneath the frozen rays of that winter sun which pours down on us without love, like perfect song. A bird was warbling in a window cage. At that moment I grew aware of the mystery which urges men to create certain strange forms. And the creation appeared more extraordinary than the creators. Perhaps the most amazing sensation passed on to us by prehistoric man is that of presentiment. It will always continue. We might consider it as an eternal proof of the irrationality of the universe. Original man must have wandered through a world full of uncanny signs. He must have trembled at each step.

Giorgio de Chirico was an Italian artist and writer born in 1888, who founded the movement of Metaphysical Painting. He was inspired by Neitzsche and Shopenhauer in his philosophy, that informed both his visual and written work, and his own writing was a major source of inspiration to Andre Breton and the Surrealist Movement. This essay was first published in 1928 by Breton in ‘Surrealism and Painting’.

Five of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel August 17, 2024

The Five of Swords is a card of undoing, of our dreams that come crashing down. Here the Swords which have been gently building start to fall apart like a house of cards. This is the representation of a failed hypothesis...

Name: Defeat, the Five of Swords

Number: 5

Astrology: Air, Venus in Aquarius

Qabalah: Gevurah of Vau

Chris Gabriel August 17, 2024

The Five of Swords is a card of undoing, of our dreams that come crashing down. Here the Swords which have been gently building start to fall apart like a house of cards. This is the representation of a failed hypothesis.

In Rider, we find a smiling rogue picking up swords that have been lost in battle. Behind him two men mourn before a sea. The sky is cloudy. Two swords lay on the ground, and three are in hand. He is picking up the pieces, unmoved by what has occurred.

In Thoth, we find a reversed pentagram, a falling star made of chipped swords. Geometric figures sputter about it with falling petals. The card has the violet of Aquarius and the Green of Venus. Venus in Aquarius has dreams and desires, but lacks the grounding to actualize them, creating a distance and alienation.

In Marseille, we have a single central sword whose tip is weaving through the four arched around it. Through Qabalah, we find it signifies “The Anger of the Prince”.

The Anger of the Prince is Defeat. It is an anger toward reality, after his expectations, measurements, methods and plans were undone..

This is not defeat at the hands of another, but self undoing.

My great grandfather was a Mason, and a piece of advice he gave me was to “measure twice, cut once”.This card occurs as a result of incorrect measurements. We can imagine a car stranded out of gas on the side of the road, a disappointed couple and an amused tow truck driver taking a modern form of the Rider card..

The suit of Swords pertains to the mental sphere, which is the origin of our many defeats, foibles, expectations, and visions which fall apart when they meet the real world.

Aesop’s Astronomer, who despite his calculations of the stars falls into a well.

While the Five of Wands gives us the image of a tyrannical ruler who weighs too heavily upon his people, the Five of Swords is the image of a totally removed ruler, like Marie Antoinette, who when told that the peasants had no bread, replied: "Then let them eat cake."

While we often attribute the ‘airheadedness' of these dynamics to an ‘overdeveloped imagination’, it is in fact a failure of imagination.

It makes me think of how so many want to make art, only they need millions of dollars, expensive equipment, and the like, while the truly great artists find a way to bring their vision into reality with what they have in hand. They set aside unreal expectations for the sake of the art itself. Which requires more imagination?

The great thing about this card is that it functions as a prerequisite for the Six of Swords, which represents Science. These are the failed hypotheses, the experiments gone awry, the countless mistakes that are needed to develop a functional methodology.

When we pull this card, we are being shown a part of ourselves that holds these unreal ideas, illusions that we maintain which will be brought tumbling down by the world.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, we can be like the smiling fellow, pick up the pieces and try again. This is how we develop a true understanding of the world.

A Forager’s Take on Fairytales Pt. 1

Izzy Johns August 15, 2024

Long ago in Drumline, County Clare, in the late 19th Century, an old farmer and his wife huddled for warmth in a mud hut. Many a cold winter passed, and finally, the man agreed to build his wife a house of bricks and mortar. He set to work the following Spring. Not a day had passed when the old man received a visit from a traveler, who spoke these words…

Izzy Johns August 15 2024

Long ago in Drumline, County Clare, in the late 19th Century, an old farmer and his wife huddled for warmth in a mud hut. Many a cold winter passed, and finally, the man agreed to build his wife a house of bricks and mortar.

He set to work the following Spring. Not a day had passed when the old man received a visit from a traveler, who spoke these words:

“I wouldn’t build there if I was you. That’s the wrong place. If you build there you won’t be short of company, whatever else.”

The old man paid him no mind, but sure enough, the moment he and his wife lay down to rest in their new home, they were plagued by noise and disruption. Furniture was knocked over, cutlery strewn across the floor, crockery smashed. They couldn’t get a wink of sleep. But, as sure as day, whenever they went to investigate, they found nothing and no one. The old couple sought the help of the local preacher, who recognised this as the work of the Sidhe, the Little Folk of this land. He tried to exorcize the house, but to no avail.

After five sleepless nights, the man wearily set off to the market to sell their cows. It was the Gale day, the day that their rent was due, and money was sparse. English colonisers had seized land from the Irish farmers some years before. Now they were renting it back to them, and the rent was high.

The old man got a fair price for the cows, and he stopped at a roadside pub on the way home. It was there that he encountered the traveler once again. In desperation, the man begged the traveler for advice. He would do anything so that the Little Folk would let him rest. The traveler walked him home, and took him to stand in the yard, on the far side of the house.

He said:

“Now, look out there and tell me what you see.”

[…] “The yard?”

“No,” he says, “look again.”

“The road?”

“No. Look carefully.”

“Oh, that old Whitethorn bush? Sure, that’s there forever. That could be there since the start o’ the world.”

“D’you tell me that now?”

The old man walked out to the gable o’ the house, called [him], then says, “come over here.”

He did.

“Look out there, and tell me what do you see?”

He looked out from that gable end, and there, no farther away than the end o’ the garden, was another Whitethorn bush, standing alone.

“Now,” says the old man, “I told you. I warned you. The fairies’ path is between them bushes and beyond. And you’re after building your house on it.”

Upon the instruction of the traveler, the man built two doors in either side of the house, in line with the Whitethorns. From then on, the Little Folk had a clear passage, and the man and his wife were not bothered again.¹

“The higher you climb, the further you travel, the greater the view”

British Goblins, 1880. Wirt Sikes.

I was very struck by this account. It feels different to the rich, meandering folk-tale jewels I love so much, that are wrapped in mythos and allegory. Instead, this tale falls into the realm of family and community stories, that are still “lived in”, in this case, by the old couple’s grandson, who told this story to Eddie Lenihan in the living room of the very same house. He said that he still leaves the two doors ajar each night so as to let the fairies pass. There’s no use in locking them, he says, for they’ll only be open again by the morning.

Make no mistake, this story is not hearsay. A book of fairy tales might read like a book of fiction, but it isn’t. What we see in this tale, and so many others like it, is a relic of a complex faith system from times gone by, and it’s important that we storytellers hold it in that way. This story comes from Ireland, where the fairies are called Sídhe, or Sí, though often called by euphemisms to avoid catching their attention. The Sidhe are the descendants of the people of Danu, the Tuatha Dé Danann, a race of fallen Gods and Goddesses that dwell in the liminality between our world and the otherworld, the An Saol Eile. It’s only fair to acknowledge their providence, not least is it a crucial act of cultural preservation.

Fairies have a range of habitats depending on where you are live. In Ireland, they are particularly fond of two places: a lone Whitethorn (Hawthorn) tree, and the forts - those grand, grassy mounds of earth, often covered in a greater diversity of wild plants than their surroundings. In this tale, the old couple has disturbed not a habitat, but a passage between habitats. More savvy builders would have driven four hazel rods into the ground, marking out the proposed foundations of the house. If by the next day any rod had moved, the house should be built elsewhere.

The fairies in this story star in a role that I’ve seen in countless tales; defending their habitat from ecological destruction. Here, they were able to communicate with the intruders and resolve the problem quickly. It’s a good thing that the old couple were forthcoming. Fairies will always give warnings, but it’s perfectly within their power to cause grave suffering if those warnings aren’t heeded. They can be at best didactic and at worst violent, but they have no interest in troubling a person who isn’t troubling them. I can’t condone the violence, but I marvel at how proficient they are at protecting and stewarding the land. Plus, they greatly enrich the ecosystem. Various tales see fairies fertilizing soil for generous farmers, and producing abundances of wildflowers and fungi. It’s said that the rings of mushrooms we see in woodlands and meadows are where they’ve danced.

The Intruder, c.1860. John Anster Fitzgerald.

Thinking about this with an Ecologist’s gaze, fairies are a fascinating species. They might well be a larger genus with loads of regionally-specific variants like small people, spriggans, buccas, elves, bockles and knockers, browneys, goblins, dryads, gnomes and piskies. There’s a wealth of anecdotal evidence of their existence, thousands and thousands of stories, stretching back millenia, yet we’ve never successfully captured and studied them. Perhaps what makes this species most unique is their ability to outwit ours. Their cunning gently prods at our human arrogance, contesting our claim to be the most “developed” of species.

Far less frequently in the UK do we hear tales of the Little Folk interfering with larger property developments. In London, for example, you’ll scarcely come across a piece of land that hasn’t been leveled ten times over, and most Whitethorns are confined to cultivated hedges. I wonder how many forts have been destroyed in my neighborhood. Our lack of understanding of the fairies’ life cycles and physiology makes it pointless to speculate on why larger builds don’t experience ramifications from the little folk. It’s hard not to wonder if heavy machinery, giant crews of contractors and big blocks of hundreds of dwellings haven’t been too much for the fairies to contend with. I hate to think that, unbeknownst to us, urbanization might have wiped them out. If fairies are still around, it’s clear that they’re gravely endangered.