Three of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel October 19, 2024

The Three of Swords is the beginning of intellectual development and the origin of understanding. This materializes as, of course, pain. It is the card of primordial heartbreak and separation that necessitates thought…

Name: Sorrow, the Three of Swords

Number: 3

Astrology: Saturn in Libra

Qabalah: Binah of Vau

Chris Gabriel October 19, 2024

The Three of Swords is the beginning of intellectual development and the origin of understanding. This materializes as, of course, pain. It is the card of primordial heartbreak and separation that necessitates thought.

In Rider, we have a simple, brilliant, iconic image: a heart pierced by three swords on a rainy background.

In Thoth, a flower falls apart as three swords pierce its center on a dark organic background. The card relates to Saturn in Libra, the little flower crushed by leaden weight.

In Marseille, we have two bent swords and one central sword atop two flowering stalks, upon which there are 22 leaves and berries, the number of Hebrew letters. As the card has the number 3, it relates to Binah, Understanding.As Swords it is the Prince. Thus, sorrow is the understanding of the Prince.

This is a deeply Buddhist card. We can take the Prince in question to be Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, and see the realization of his truth that Life is Suffering. Freud, perhaps offers a clearer view of this: sorrow is separation from the Mother. It is only when the child is not fully one with the mother, when their needs are not met perpetually, that sorrow begins. Tears start, tears that mean “give me what I want”.

The Buddha recognizes that this sorrow is simply a fundamental part of ourselves. We desire, and so we sorrow. Without wants and needs, there would be no sorrow. Without love, there would be no heartbreak. This sort of pain is the source of our knowledge, and our need to develop knowledge. If we never burnt ourselves, we would not know to beware of fire, if we had not been stung, or bitten, we wouldn’t know the dangers around us. If we had not fallen, we wouldn’t know how to stand. These endless sorrows develop our understanding.

To wish for an unbroken heart, an uncrushed flower, is to wish for an empty mind. This is what meditation allows us to do. It forms the ability to return to the unbroken, the whole. One may wish to spend their whole life meditating, to be untouched and unharmed by the world, but this is only one small step on our journey through the tarot.

When we pull this card, we may come to understand something which has been troubling us, we may realize what the problem is, but not how to deal with it. Knowledge is not curative. This is a start to a strategy. This is a problem that needs fixing.

By bringing our attention to this issue, we can move toward greatness.

‘Dont Look Back’ and Self Made Myth

Ana Roberts October 16, 2024

On the road to immortality, Dylan was learning from his mistakes and shaping the mythology of himself. One of those mistakes, it seemed, was inviting a young documentary filmmaker on tour with him. ‘Don’t Look Back’ captures Dylan in a way he never would be captured again, and for a good reason…

Ana Roberts, October 16th, 2024

In 1967, Bob Dylan was a prophet speaking truth to power with his guitar and voice, and informing the minds of a million young people searching for direction. He was settled in this role and comfortable enough to experiment within it. Yet just 2 years earlier, the foundations of this persona were a little less steady. On the road to immortality, Dylan was learning from his mistakes and shaping the mythology of himself. One of those mistakes, it seemed, was inviting a young documentary filmmaker on tour with him. ‘Don’t Look Back’ captures Dylan in a way he never would be captured again, and for a good reason.

D.A. Pennebaker followed Dylan in 1965, touring England, at the very start of his electric revolution, still playing live shows with his acoustic and harmonica. He is seen hanging with Joan Baez, Donovan, and a group of managers, journalists, and fans, with Allen Ginsberg appearing in the background of the now iconic opening sequence set to “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” a proto-music video before the term existed. It is a remarkably candid film and stands as a pinnacle of 1960s-era cinéma vérité. Pennebaker does not interact with him; he serves as a fly on the wall and tries to, through the powers of sheer observation, understand the truth of his subject. The Dylan that the public sees in this film largely aligns with his established persona—a mercurial, elusive genius—yet the consistency of this behavior reveals a soft inauthenticity. The more we watch him interact with journalists and play the role of the aloof prophet, the more his predictability begins to erode the myth. Instead of reinforcing his mystique, it undermines it. We see not a spontaneous artist but an actor fully conscious of his role. At once relentlessly confrontational and perpetually elusive, his time on tour is punctuated by petulant encounters with journalists, lazy days, and frustrated evenings spent in hotel rooms, trading songs with Baez while he sits at his typewriter, and the occasional flash of anger. Where the consistency of Dylan begins to undermine his façade, it is the latter of these, the moments of anger, which one can guess are to blame for Dylan’s refusal to ever be filmed by him. Even in these moments, as he tries to recover from the broken façade he inadvertently revealed, we can see shivers of regret in the young Dylan’s eyes—fear that his image of a “cool cat,” unfazed by the world around him, has slipped in front of an audience and, worse, a camera.

There is a single scene that stands out, and one that resides most strongly in the public consciousness of the film, where Dylan, while his hotel room is filled with various figures from the contemporary British music scene, including Donovan and Alan Price, having recently left the Animals, tries to get to the bottom of who threw a glass out the window. It is the antithesis of the Dylan he presents: he is not the elusive figure, the freewheelin’ Dylan, the mocking Dylan. Instead, he is a petty, angry figure concerned about his own perception. He tells a drunken Englishman who he suspects threw the glass that “I ain’t taking no fucking responsibility for cats I don’t know, man… I know a thousand cats that look just like you.” Later, when the dust has settled, Donovan plays a song and Dylan, immediately after, plays “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” a pointed upstaging of the younger artist, clearly in the presence of his hero. These ten minutes of footage stand alone in Dylan’s career—a glimpse behind the glass onion. It is in these moments that we see such concern about the way he is presented, agonizingly self-aware and furious at the possibility that he might not be in full control of his image. Yet this does not weaken Dylan’s genius; it amplifies it. It is the reason for his success. He is a master at building the mythology around him, knowing, like Freud, that if he gives too much of himself, too inconsistent a version of himself, it won’t be a strong bedrock on which the fans can create the myths. ‘Don’t Look Back’ stands alone in documentaries because it pays attention to the man behind the curtain, and Dylan’s work remains more powerful when the curtain is not pulled back.

“‘Another Side of Bob Dylan’ is the Temptation of Christ, the 40 days and nights in the desert—it is the prophet going alone, leaving those who believe they need him, only to force them to dig deeper into his message.”

Bob Dylan in the hotel room in ‘Dont Look Back’. (1967).

It is not this film alone that reveals the personal construction of Dylan, though it gives a wondrous insight into it. Between 1963 and 1965, Dylan put out five albums, and to listen to each is to hear in stark detail the active construction of an icon. He refines his ability with each album, taking the elements that most readily captured his listeners and expanding them constantly, while refusing to be pigeonholed in style or content. We can see this perhaps most clearly in the three-album run of ‘The Times They Are a-Changin’’, ‘Another Side of Bob Dylan’, and ‘Bringing It All Back Home’. ‘The Times They Are a-Changin’’, his third record and the first to contain all original songs, builds off the previous album, leaning into revolutionary-minded, political anthems and civil-rights era ideas, blended with majesty into his brand of beat-inspired folk music. It is a logical continuation to ‘The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan’, cementing his reputation as the voice of his generation, reporting on the issues in ways only the kids understand. Yet ‘Another Side of Bob Dylan’, released some eight months later, entirely rejects this image. The name itself is a refusal to be defined as anything, a rejection of the label of prophet, which only makes the role more powerful as listeners try to rectify the two. “My Back Pages” confronts any attempts to pinpoint political views: “Equality, I spoke the word / As if a wedding vow / Ah, but I was so much older then / I’m younger than that now,” a cry that he is changing, an offer to attempt an understanding of what he believes. ‘Another Side of Bob Dylan’ is the Temptation of Christ, the 40 days and nights in the desert—it is the prophet going alone, leaving those who believe they need him, only to force them to dig deeper into his message.

‘Bringing It All Back Home’ is the completion of this journey—it is when Dylan knew he had found greatness. He blends folk with rock music deftly, never allowing any song to fall simply into either category. Gone are the directly political songs; rather, he is able to embed the possibility of revolution into every line, turning songs of the personal into rambling prophecies of the last days of earth, as with “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” Each line can be taken as its own maxim, its own prophecy, and Dylan throughout this album confirms his role as the oracle. “He not busy being born / Is busy dying / Temptation’s page flies out the door / You follow, find yourself at war” captures this ability to at once capture specificity and remain entirely open to interpretation. *Bringing It All Back Home* is the realization that the prophet is most powerful when they can never be understood. Each song makes you confident you are in the presence of, and listening to, something important, and if you don’t understand it in time you will—the prophecy will reveal itself. It is in these three albums we see Dylan embrace the inauthentic and use it to further his message; it is here we see him realize that authenticity leads to understanding, and when you are understood your message ends. Dylan embraces the inauthentic, and it lets him live forever.

Ana Roberts is a writer, musician, and cultural critic.

Sentences on Conceptual Art (1969)

Sol LeWitt October 15, 2024

Two years before this text was written, Sol LeWitt published ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’ which can rightly be seen as the first public recognition of a new art form that was sweeping the avant-garde. LeWitt was a pioneering artist in this field, and as he proved in that writing, it’s greatest practicing theorist. This text is a follow up to that work, written when ‘Conceptual Art’ as a genre is widely accepted and recognised. His goal, then, was not to explain but to illuminate, and provide a set of maxims that artists can follow to create art that transcends the boundaries of what was seen as possible.

Sol LeWitt, 123/Six Three-Part Variations Using Each Kind of Cube Once, 1968-1969.

Sol LeWitt, October 15th, 2024

Two years before this text was written, Sol LeWitt published ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’ which can rightly be seen as the first public recognition of a new art form that was sweeping the avant-garde. LeWitt was a pioneering artist in this field, and as he proved in that writing, it’s greatest practicing theorist. This text is a follow up to that work, written when ‘Conceptual Art’ as a genre is widely accepted and recognised. His goal, then, was not to explain but to illuminate, and provide a set of maxims that artists can follow to create art that transcends the boundaries of what was seen as possible. It was first published in 1969 in issue 1 of "‘Art-Language’.

1. Conceptual Artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.

2. Rational judgements repeat rational judgements.

3. Illogical judgements lead to new experience.

4. Formal Art is essentially rational.

5. Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.

6. If the artist changes his mind midway through the execution of the piece he compromises the result and repeats past results.

7. The artist’s will is secondary to the process he initiates from idea to completion. His wilfulness may only be ego.

8. When words such as painting and sculpture are used, they connote a whole tradition and imply a consequent acceptance of this tradition, thus placing limitations on the artist who would be reluctant to make art that goes beyond the limitations.

9. The concept and idea are different. The former implies a general direction while the latter are the components. Ideas implement the concept.

10. Ideas alone can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical.

11. Ideas do not necessarily proceed in logical order. They may set one off in unexpected directions but an idea must necessarily be completed in the mind before the next one is formed.

12. For each work of art that becomes physical there are many variations that do not.

13. A work of art may be understood as a conductor from the artist's mind to the viewer's. But it may never reach the viewer, or it may never leave the artist's mind.

14. The words of one artist to another may induce an ideas chain, if they share the same concept.

15. Since no form is intrinsically superior to another, the artist may use any form, from an expression of words, (written or spoken) to physical reality, equally.

16. If words are used, and they proceed from ideas about art, then they are art and not literature, numbers are not mathematics.

17. All ideas are art if they are concerned with art and fall within the conventions of art.

18. One usually understands the art of the past by applying the conventions of the present thus misunderstanding the art of the past.

19. The conventions of art are altered by works of art.

20. Successful art changes our understanding of the conventions by altering our perceptions.

21. Perception of ideas leads to new ideas.

22. The artist cannot imagine his art, and cannot perceive it until it is complete.

23. One artist may mis-perceive (understand it differently than the artist) a work of art but still be set off in his own chain of thought by that misconstrual.

24. Perception is subjective.

25. The artist may not necessarily understand his own art. His perception is neither better nor worse than that of others.

26. An artist may perceive the art of others better than his own.

27. The concept of a work of art may involve the matter of the piece or the process in which it is made.

28. Once the idea of the piece is established in the artist's mind and the final form is decided, the process is carried out blindly. There are many side-effects that the artist cannot imagine. These may be used as ideas for new works.

29. The process is mechanical and should not be tampered with. It should run its course.

30. There are many elements involved in a work of art. The most important are the most obvious.

31. If an. artist uses the same form in a group of works, and changes the material, one would assume the artist's concept involved the material.

32. Banal ideas cannot be rescued bv beautiful execution

33. It is difficult to bungle a good idea.

34. When an artist learns his craft too well he makes slick art.

35. These sentences comment on art, but are not art.

Sol LeWitt (1928-2007) was an American artist and art theorist who was a founding figrue in the ‘Conceptual Art’ and ‘Minimalist’ movements.

The Chariot (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel October 12, 2024

The Chariot secures the domain of the royal cards which have come before it. This is the card of empire and of the strength which maintains it. Each iteration shows an armored figure and his chariot...

Name: The Chariot

Number: VII

Astrology: Cancer

Qabalah: Cheth

Chris Gabriel October 12, 2024

The Chariot secures the domain of the royal cards which have come before it. This is the card of empire and of the strength which maintains it. Each iteration shows an armored figure and his chariot.

In Rider, we find a stern looking man adorned in beautiful armor. His skirt bears alchemical symbols, and his shoulder pads are lunar faces. He has a starry crown and wields a baton. His gray chariot has a winged disk, and starry curtains, and At the center is the mark of a wheel and axle. His chariot is drawn by two monochrome sphinxes. Behind him is a large kingdom.

In Thoth, we find a traditional knight in amber armor seated in Lotus position. He bears cup of the Holy Grail, blue with the red blood of Christ in the center. His helmet is topped with a blue crab. His red chariot is drawn by the four beasts in sphinx form.

In Marseille, we find a young man with long blonde hair, wearing colorful armor with shoulder pads which are lunar faces. He bears a baton. His chariot is drawn by two horses of red and blue.

In each iteration, we find an armored man balancing dual forces, the hard and the soft, the severe and the gentle. The Chariot is Cancer, it is the two claws and hard shell of the crab. This is the nature of the imperial army, the hard defenses keep what is within safe.

Cancer is the sign of empire; it occupies much of July, a month named for Julius Caesar, and of course the United States was born in Cancer. Cancer is concerned with the home, and with the domain. For a crab this can be a tide pool or a rock, but for an individual or a nation, the question is how large of a home one can have. How far can our borders span? How much space can be made safe? How much space can be controlled?

The Hebrew letter associated with the Chariot is Cheth, meaning the fence. Thus the domain of Cancer establishes walls and fences, and defends them with the military. A nation’s borders are defined solely by violence, in a constant test of whether the claws of cancer can frighten away those who would seize it.

In the personal dimension, the Chariot is the car. As Gary Numan says: Here in my car I feel safest of all. I can lock all my doors; it’s the only way to live: in cars.

And as Paglia writes, advancing past “a room of one’s own” to a car of one’s own. The car is chariot, armor, and weapon all in one. It allows for endless individual travel, safety, and expansion. It is the dream of Cancer.

When we pull this card, we may have to defend our space from an imposing force, or we may have to hop in the car and make space somewhere far away.

The Power of a Heavy Sigh

Vestal Malone October 10, 2024

A mirror, a polaroid selfie, the surface of a cool mountain lake pre-immersion… we see ourselves in these reflections, but they don't explain who we are, or why, or how others perceive us. Bodies, images, faces, names, styles, reputations, and qualities of character; all a part of some definition of ourselves, yet none truly capture the whole. Only the mind's eye, carefully listening from the inside out with breath as guide, can see the physical and emotional self in their entirety...

Analogical Diagram, Tobias Cohen’s Ma’aseh Tuviyah.

Vestal Malone October 10, 2024

A mirror, a polaroid selfie, the surface of a cool mountain lake pre-immersion… we see ourselves in these reflections, but they don't explain who we are, or why, or how others perceive us. Bodies, images, faces, names, styles, reputations, and qualities of character; all a part of some definition of ourselves, yet none truly capture the whole. Only the mind's eye, carefully listening from the inside out with breath as guide, can see the physical and emotional self in their entirety.

The perfectly divine design machine of the human body may appear symmetrical but its balance is asymmetrical: our liver, gallbladder, the “good side” of our face for the family portrait, right or left handed, goofy foot or regular, all contribute to a lack of balance within ourselves. Even those that appear symmetrical - the kidneys, lungs, eyes, legs, ovaries, and arms - have subtle differences. And the gray matter, balanced atop the spine, encased by the skull, with the duties that control every aspect of our existence – the sacred left brain, the mundane right brain – separate yet united, floating and dancing with the breath. The simple wisdom of this twin organism can create a breath and relax the body without the mind's conscious choice getting in the way. The heavy sigh.

To begin to know the self from the inside out, one must invite the mind to follow as breath fills the lungs, like a pitcher filling with water. Focus and notice the body's details, truly observing each cell, and you can begin creating an opportunity to hit the “pause” and then “reset” button allowing the body to harmonize itself. The heavy sigh.

Sitting at the office or in traffic, dancing, surfing, receiving bodywork or practicing yoga are all opportunities to follow the breath with the mind, bring oxygen, and clear stagnation. The breath is the best chiropractor, especially lying or sitting still. As the lungs move to inflate and then release, travel along the mind's path until the focus blurs and flow begins. The body is designed to release itself, but it needs the mind to get out of the way as it waits for the heavy sigh. It can't be controlled, only invited, and when it comes, a powerful release to mind and body happens in the exhale.

After her University education (BA in English Literature and philosophy, minor in music), Vestal Malone followed the call to study her hobbies of yoga and therapeutic touch a the Pacific School of Healing Arts and continued in the Master's program of Transformational Bodywork with her mentors, Fred and Cheryl Mitouer, and assisting with their teaching. She went on to teach her own Therapeutic Touch workshops in Japan, hatha yoga in America, and study Cranial Sacral Therapy with Hugh Milne and John Upledger. She has had the honor of doing bodywork with professional athletes, laymen and nobility for over 25 years. Vestal is a mom, a backyard organic gardener, and sings soprano in her church choir on a little island in the middle Pacific ocean. She hails from Colorado and Wyoming and migrates every summer to her family ranch to ground in the dust of her roots.

The Seven of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel October 5, 2024

The Seven of Wands is a card fighting against the odds. It symbolizes the willingness to fight a losing battle, and bravery in spite of terrible danger.

Name: Valour, the Seven of Wands

Number: 7

Astrology: Mars in Leo

Qabalah: Netzach of Yod

Chris Gabriel October 5, 2024

The Seven of Wands is a card fighting against the odds. It symbolizes the willingness to fight a losing battle, and bravery in spite of terrible danger.

In Rider, we find a young man in a green tunic battling off 6 wands wielded by unseen enemies beneath him. His face is angry. He has no support, but he goes on fighting.

In Thoth, we find 6 fine ritual wands crushed by a simple club. This is the base creative and violent energies that overcome what is structured and established, a battering ram that breaks in an ornate door. It is Mars in Leo, so there is a strong element of Pride, this is proving oneself against authority, or defending one's name from insult.

In Marseille, we have 6 wands crossed, and one beneath. Foliage sprouts from the sides. Qabalistically it is the Love of the King. The Love of the King is prideful and brave.

This card brings to mind many great battles, not least the Battle of Thermopylae where the 300 Spartans overcame a Persian army that numbered in the hundreds of thousands. A closer fit, however, is the Battle of Bunker Hill, where raggedy American militiamen held their own against the great British army. Though they lost, they proved their bravery was a match for superior training.

Perhaps the most direct example still, is the Battle of Stamford Bridge, marking the end of the Viking age. The key figure is an unknown Viking Berserker who makes a chokepoint on Stamford Bridge, single handedly holding off the English army. He kills 40 on his own, and is finally taken down by a soldier with a spear who struck him from under the bridge.

The Seven of Wands is past the point of Victory, the Six of Wands. This is not about fighting to win, this is fighting when all is lost.

Norman Rockwell, 1943. Oil on Canvas.

This is the card of Valour, of the lone soldier fighting an entire army. These countless historical events color the card well, but its ideas can be closer to home too. This is the card for when we hold our own opinion in spite of opposition. This is going against the grain, even when it’s uncomfortable.

The Norman Rockwell painting Freedom of Speech shows it well; a lone man standing up to voice his opposing opinion to the town. This is the willingness to engage in controversy, to dissent. Of course, this is not always positive. The subject of Rockwell’s painting is a man dissenting against the consensus to build a new school after it had burned down. The battles fought bravely for pride are often quite ridiculous.

When you pull this card, you may be faced with opposition, and you must face it bravely. Speak up, even when everyone else disagrees.

Life Is Right (1904)

Rainer Maria Rilke October 3, 2024

In 1902, while attending military college an hour outside of Vienna, Austria, the 19 year old Xavier Kappus began a correspondence with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, a respected and established writer who had, many years earlier, been tutored by the very same school master as Kappus himself. Seeking advice and criticism on his poetry, over 6 years and 10 letters, Rilke taught him something altogether more important...

Rainer Maria Rilke, October 3rd, 2024

In 1902, while attending military college an hour outside of Vienna, Austria, the 19 year old Xavier Kappus began a correspondence with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, a respected and established writer who had, many years earlier, been tutored by the very same school master as Kappus himself. Seeking advice and criticism on his poetry, over 6 years and 10 letters, Rilke taught him something altogether more important - a way to understand the world and navigate the difficulties of life with wonder, love, creativity, and hopefulness. The letters were collected into a book published as ‘Letters to a Young Poet’, which remains one of the most seminal and essential works of the 20th Century. The letter reproduced here was written in November of 1904, while Rilke was in Sweden.

My Dear Mr. Kappus,

In this time that has gone by without a letter I have been partly traveling, partly so busy that I could not write. And even today writing comes hard to me because I have already had to write a lot of letters so that my hand is tired. If I could dictate, I would say a great deal to you, but as it is, take only a few words for your long letter.

I think of you, dear Mr. Kappus, often and with such concentrated wishes that that really ought to help you somehow. Whether my letters can really be a help, I often doubt. Do not say: yes, they are. Just accept them and without much thanks, and let us await what comes.

There is perhaps no use my going into your particular points now; for what I could say about your tendency to doubt or about your inability to bring outer and inner life into unison, or about all the other things that worry you—: it is always what I have already said: always the wish that you may find patience enough in yourself to endure, and simplicity enough to believe; that you may acquire more and more confidence in that which is difficult, and in your solitude among others. And for the rest, let life happen to you. Believe me: life is right, in any case.

And about emotions: all emotions are pure which gather you and lift you up; that emotion is impure which seizes only one side of your being and so distorts you. Everything that you can think in the face of your childhood, is right. Everything that makes more of you than you have heretofore been in your best hours, is right. Every heightening is good if it is in your whole blood, if it is not intoxication, not turbidity, but joy which one can see clear to the bottom. Do you understand what I mean?

And your doubt may become a good quality if you train it. It must become knowing, it must become critical. Ask it, whenever it wants to spoil something for you, why something is ugly, demand proofs from it, test it, and you vail find it perplexed and embarrassed perhaps, or perhaps rebellious. But don’t give in, insist on arguments and act this way, watchful and consistent, every single time, and the day will arrive when from a destroyer it will become one of your best workers— perhaps the cleverest of all that are building at your life.

That is all, dear Mr. Kappus, that I am able to tell you today. But I am sending you at the same time the reprint of a little poetical work * that has now appeared in the Prague periodical Deutsche Arbeit. There I speak to you further of life and of death and of how both are great and splendid.

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) was an Austrian poet and novelist whose lyricism and literary intensity expanded the possibilities of the German language.

Disturbed Images

Lamia Priestley October 1, 2024

A roll of belly fat melts into a makeup-caked face; a bag of chips morphs into a family portrait; a butt cheek transforms into a policeman’s bicep. Gross and sickly, loud and pink, Frank Manzano’s collection of video works, Current Value (2023), uses AI imagery to depict the grotesque in everyday scenes of American suburban life—fistfights, plastic surgery, arrests.

Lamia Priestley October 1, 2024

A roll of belly fat melts into a makeup-caked face; a bag of chips morphs into a family portrait; a butt cheek transforms into a policeman’s bicep. Gross and sickly, loud and pink, Frank Manzano’s collection of video works, Current Value (2023), uses AI imagery to depict the grotesque in everyday scenes of American suburban life—fistfights, plastic surgery, arrests.

Still from Holistic Consumption Challenge (Current Value), Frank Manzano. (2023).

Rapid cuts between faces result in pile ups of interchangeable characters. An endless treadmill of trash, plastic consumer products, and open mouths, the videos’ choppiness creates what the Chicago-based artist describes as “the human parade”—a crazed illustration of people as stuff. Manzano describes his work as an exploration of “consumerism, massification, the loss of the self.” These themes are felt not just in the works’ subject matter but in the evidence of the mass market AI tools Manzano uses to make many of his images.

Manzano has a fondness for corpulent characters, big butts, cellulite, stretched thighs and teethy smiles. Outside of his focus on flesh, the videos themselves exert a materiality in their reference to the aesthetics of consumer visual culture and their artefacts. There’s the digital lines of security footage, the jacked up saturation of reality TV, the studio lighting of an 80s sitcom, the low res crunchy feel of camcorder home videos. The images look either consumer-grade (camcorder) or like something used to capture consumers (CCTV). But amongst the visual styles referenced in Manzano’s work, one can distinguish something entirely new, the artefacts of AI images.

To create this pastiche, Manzano uses a combination of his own photos, sourced images and ones he generates with AI image tools like Wombo. On a visual level, the artefacts of AI images—the airbrushed smooth skin, confused edges between fingers, gibberish logos and half-baked eyes—contribute to a feeling of the uncanny in these illustrations of the American underbelly. More than just a formal contribution though, these artefacts place the images into a context. Viewers who, over the past few years, have developed a familiarity with AI generated images online, will recognise them here and have some understanding of the process by which they are created—using a dataset of preexisting images. It’s clear that although Current Value’s images have the trademarks of documentary or recorded reality, many of them aren’t real.

“There’s something profane in the limitation of a finite dataset. The images have no hope of transcendence.”

The disturbing nature of Manzano’s videos is due, not to this irreality, but rather to the images’ self-aware embrace of their artificial generation. The AI artefacts are significant because of what they mean in the context of Manzano’s unaspiring video world. Not only are his subjects debased but so too are the images—a perfect marriage of subject and form.

Origins of Fetishization (Current Value), Frank Manzano. 2023.

The philosopher Hannes Bajohr offers a useful framework for understanding this earthbound quality of AI images in his article Algorithmic Empathy: Toward a Critique of Aesthetic AI (2022). Bajohr advocates for interpreting AI arts on their own terms, looking at how they’re made—their “technical substrate”—to develop their aesthetic critiques. Bajohr draws a parallel between artificial neural networks and the ancient aesthetic principle of mimesis—the attempt to imitate or reproduce reality in the creation of art. He outlines two opposing concepts of imitation as it relates to AI images. The first he attributes to the philosopher Hans Blumenberg’s explanation. It describes imitation as construction, which sees “the approximation of an existing state through the inference of the rules that bring it about.” The second concept of imitation, which better describes AI image making, is “imitatio naturae” (imitation of nature). A classical idea that was repopularised in the Renaissance, “imitatio naturae” sees imitation as a mere repetition of the real without the “procedural insight” of imitation as construction. In the case of AI image making, “nature” would be the dataset, and so that from which all representations are derived.

This first approach to imitation, that of construction, implies the possibility of depicting something new. Bajohr emphasises that with the knowledge of a thing’s creation—of its building blocks—moving beyond that thing is possible while in “imitatio naturae”, the representation derives directly from the thing itself. Nature, and so the dataset, is the absolute resource. An artificial neural network can’t truly imagine anything beyond its own dataset, never something outside of that which has already been represented.

There’s something profane in the limitation of a finite dataset. The images have no hope of transcendence. Image generators are so far unable to replicate the mysterious process by which a great artist goes about transforming an ordinary landscape into an image that might produce ineffable revelations in its viewers. The artist—studying how light falls, the relationships of colours, the phenomenon of perspective—might inexplicably assemble a few strokes of paint to reveal something much greater than valleys, woods, hills and streams, much greater than nature.

Manzano’s images are trapped. His subjects lead unambitious lives, marginalised by a cycle of consumerism, greed, lust, violence, and vanity; they're governed by their instincts, unable to escape themselves. So too, AI images exist only in immanence. Image generators simulate master artists’ styles from the past, merely recycling them, destined to make unambitious copies.

Current Value’s images are provocations. They’re affective, disturbing representations of the gutters of material culture because they themselves belong there, unable to dream themselves out.

Lamia Priestley is an art historian, writer and researcher working at the intersection of art, fashion and technology. With a background in Italian Renaissance Art, Lamia is currently the Artist Liaison at the digital fashion house DRAUP, where she works with artists to produce generative digital collections.

The Nine of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 28, 2024

The Nine of Wands is a card of perseverance through darkness. It represents the indomitable will of the lone survivor, who has the strength necessary to make it through to the end...

Name: Strength, the Nine of Wands

Number: 9

Astrology: Moon in Sagittarius

Qabalah: Yesod of Yod

Chris Gabriel September 28, 2024

The Nine of Wands is a card of perseverance through darkness. It represents the indomitable will of the lone survivor, who has the strength necessary to make it through to the end.

In Rider, we find a bandaged and raggedy man, standing with the help of one of the nine wands. Yet he is standing. This is a survivor who bears the marks of his struggle. Around him are 8 wands stuck in the ground. While the rest have gone or died, he remains.

In Thoth, we find the 9 wands as arrows. 8 Lunar arrows coming down. The central wand is connecting the Moon below to the Sun above. In many ways this is the most ritualistically significant card in the Thoth deck. It symbolizes the ritual of the Great Work of Thelema, that of Samekh. The movement past the Psyche and toward the Dæmon or Genius. This is the Mysterium Conjunctionis of the Alchemists, the marriage of the Sun and Moon.

In Marseille, we find a similar arrangement to Thoth, as 8 wands cross one another and a central wand is beneath them. Through Qabalah we find the name of this card to be “The Foundation of the King”. The Foundation of the King is Strength.

In some ways this is a dark card, concerned with immense struggle and difficulty, but here Nietzsche’s wisdom of “what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger” is affirmed. This is the path necessary for greatness.

This card makes me think of Apollo 11 and the “Moonshot”, mankind making the terrible and difficult journey through space to reach the Moon and the achievement of the impossible.

It also calls to mind the Star Spangled Banner:

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O'er the ramparts we watch'd, were so gallantly streaming?

And the Rockets' red glare, the Bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our Flag was still there;

The flag still standing amidst the chaos of war.

This is Nietzsche’s will to power that has brought man through the darkness of time. Even more, it is the will to dream and to achieve what is beyond - it is the best in us. Nietzsche even symbolized it with archery; in Zarathustra he feared this tendency could cease: Alas! there cometh the time when man will no longer launch the arrow of his longing beyond man—and the string of his bow will have unlearned to whizz!

The Nine of Wands is the arrow of our longing, the rocket to the moon, and the golden thread in the Labyrinth. It is what keeps us going.

When we pull this card, we may be faced with struggle and difficulty, but we must and will come out of it stronger. We may also be inspired with a great goal, a dream that we must achieve. It may be that this great dream helps us through the darkness.

On the Grasshopper

Ale Nodarse September 26, 2024

In November of 2017 a grasshopper was found lodged within the depths of Vincent van Gogh’s 1889 Olive Trees. Conservators celebrated the quiet revelation. Such an insect, they suspected, might finally divulge the season of the painting’s completion, the month — within that most productive, and final, year of van Gogh’s life — in which turbulent oil had come to rest. Further searching through pigment ensued. Tracing the most minute of ripples, as if to follow the insect’s final movements, proved futile. No such eddies emerged. The grasshopper, they concluded, died before it had been sealed in its oily envelope...

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, 1889. Oil on canvas, Nelson Atkins Museum, Kansas City.

Ale Nodarse, September 26, 2024

“And the almond tree shall flourish, and the grasshopper shall be a burden.” — Vincent van Gogh¹

“Terror and a beauty insoluble are a ribband of blue woven into the fringes of things both great and small.” — Annie Dillard²

In November of 2017 a grasshopper was found lodged within the depths of Vincent van Gogh’s 1889 Olive Trees.³ Conservators celebrated the quiet revelation. Such an insect, they suspected, might finally divulge the season of the painting’s completion, the month — within that most productive, and final, year of van Gogh’s life — in which turbulent oil had come to rest. Further searching through pigment ensued. Tracing the most minute of ripples, as if to follow the insect’s final movements, proved futile. No such eddies emerged. The grasshopper, they concluded, died before it had been sealed in its oily envelope.

The plein-air painter knew intimately the grasshopper (or sprinkhaan, in the artist’s native Dutch) and its kin. He complained of the travails of painting “on the spot itself” in a letter to his brother Theo, four years before Olive Trees was painted (July 14, 1885):

“I must have picked a good hundred flies and more off the 4 canvases that you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand etc. — not to mention that, when one carries them across the heath and through hedgerows for a few hours, the odd branch or two scrapes across them &c. Not to mention that when one arrives on the heath after a couple of hours’ walk in this weather, one is tired and hot. Not to mention that the figures don’t stand still like professional models, and the effects that one wants to capture change as the day wears on.”

The grasshopper of the Olive Trees, one suspects, arrived in such a bout of flies, or with a wind of dust and sand, or perhaps by a branch depositing the insect’s carcass upon wet canvas. In any case, the painter’s not to mentions, his niet meegerekend — or, more accurately, his “not counted (any)mores” — disclose, like the grasshopper, unanticipated revelations. For after a concession to his reader he does indeed count: a good hundred, 4, a few, or two, a couple.

Van Gogh rendered the canvas a thing which absorbs. Flies (living, or like the grasshopper, already dead) are drawn to it; dust and sand (and the innumerable particulates residing in his “etc.”) cling to it; branches scrape it. Its centimeters of oil testify still to each of these touches, depositions and engravings. But between the first and second not to mentions a change occurs. The painter describes himself absorbed, as if within a landscape that will, regardless of resistance, enumerate: that is, bring itself to his attention and to his counting. He, like his painting, transgresses dimensions. In oil as on ground, he moves not only “across the heath” but “through the hedgerows” (door de hei in Dutch). While recent exhibitions have cast Van Gogh’s images as flat, albeit immense, projections, to speak of the artist’s paintings is inevitably to speak of this movement through and to trace the former carrying — the dragging resistance — of his own body and brush.

“The ground that was painted and the ground that was tilled became increasingly one and the same.”

In the third not to mention the artist turns to his body — tired and hot — before moving a final time to the bodies of others. “The figures don’t stand still.” His complaint formed a critique of those who, like the painter Gustave Courbet, predicated their realism upon a return to the studio. (Of the figures within Courbet’s 1849 Stone Breakers, a work perennially invoked as foundational to the Realist movement, the painter wrote nonchalantly: “I made an appointment with them at my studio for the next day.”)⁴ Whereas Courbet conceived of the figure — of the peasant — as a transferable image disposed to the economics of the studio, Van Gogh insisted on his own absorption within the life of another. “The more I work on it,” he continues in the same to Theo, “the more peasant life absorbs me (me absorbeert).”⁴

Vincent Van Gogh, Women Picking Olives, 1889. Oil on Canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Through his work, the ground that was painted and the ground that was tilled became increasingly one and the same. The elements which Van Gogh would characterize as not mentionable –– flies, dust, and detritus –– would become, if at first paradoxically, proof. Proof of being there. They mark him and his canvases as they mark the laboring bodies to which he bore witness (which included women at work amidst those very trees.) The not mentionables insist on paintings not just as images but as objects. They make a proposition, too: that beauty lies in the counting and in the keeping hold of fragments which, however small, remain singular. Beauty, of such a kind, insists on the insolubility of seemingly dissolved parts; on the ribbon which may be picked out, to draw from Dillard’s analogy, from the greater weave. Beauty is an insistence on presence.

The painter, and his canvas, hold space for the ‘not to mention’ to be mentioned still. And since questions of recognition become questions of ethics, its insistence ought to weigh on us. What would it mean, the painting asks, to consider the grasshopper? What would it mean to be burdened by that which appears — all but — gone?

¹Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh (Amsterdam, September 18, 1877. No. 131). The letter was composed after van Gogh attended Rev. Jeremie Meijjes’s Sermon on Ecclesiastes XI:7–XII:7. For the original and translated letters, see vangoghletters.org.

²Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (Harper’s Magazine Press, 1974), 24.

³ “Grasshopper Found Embedded in van Gogh Masterpiece,” on the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art’s site. Link: https://nelson-atkins.org/grasshopper-found-embedded-van-gogh-masterpiece/.

⁴ Gustave Courbet, Letter to Francis Wey (November 26, 1849), translated in Marilyn Stokstad and Michael Cothren, Art History (Boston: Prentice Hall, 2011), 972. See Linda Nochlin, Realism: Style and Civilization (Baltimore: Penguin, 1971), 120–1; and, T. J. Clark, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 79–81.

⁵ Van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh (Neunen, on or about Tuesday, July 14, 1885. No. 515.).

Alejandro (Ale) Nodarse Jammal is an artist and art historian. They are a Ph.D. Candidate in History of Art & Architecture at Harvard University and are completing an MFA at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art. They think often about art — its history and its practice — in relationship to observation, memory, language, and ethics.

Head, The Monkees and the Search of Authenticity

Ana Roberts September 24, 2024

In 1968, Micky Dolenz jumped off the Gerald Desmond Bridge. Some eighty minutes later, he did it again, this time joined by the rest of The Monkees—Peter Tork, Davy Jones, and Michael Nesmith. Head, the 1968 film penned by Jack Nicholson and starring The Monkees, was the vehicle for this bridge jump—a filmic suicide that served equally as a career one...

Micky Dolenz falls from the Gerald Desmond Bridge, Head (1968).

Ana Roberts, September 24th, 2024

In 1968, Micky Dolenz jumped off the Gerald Desmond Bridge. Some eighty minutes later, he did it again, this time joined by the rest of The Monkees—Peter Tork, Davy Jones, and Michael Nesmith. Head, the 1968 film penned by Jack Nicholson and starring The Monkees, was the vehicle for this bridge jump—a filmic suicide that served equally as a career one. Not that there was much life left in The Monkees by 1968; the final episode of their show had aired in March, and their latest album, The Birds, the Bees & the Monkees, had failed to top the charts in America and didn’t even break the top ten in the UK—their first to miss both marks.

The Vietnam War, the assassinations of both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, riots in Chicago, and Soviet pressures across Eastern Europe all contributed to a waning optimism, within which there was hardly a place for the naïve antics of the Prefab Four. Yet Head is far from naïve. It is a psychedelic experiment—intentionally mind-numbing and academically stimulating—serving as a fourth-wall-breaking political critique of everything from the American collegiate sports system to dandruff commercials, with war, media, and reality thrown in for good measure. The film flopped spectacularly. It made just $16,000 from its $750,000 budget and was derided by Monkees fans, hippies, academics, and critics alike. It was too conceptual for the core fan base, mostly teen girls, and too Monkees for anyone else the film was aiming for.

Yet Head has prevailed. In the years following its release, it built a cult following and achieved a niche but significant level of critical success, regarded as a cornerstone object of the era that encompasses the themes, politics, and feelings of the late '60s. It was entered into the Criterion Collection in 2010 and hailed by Criterion critic Chuck Stephens as “arguably the most authentically psychedelic film made in 1960s Hollywood.” Stephens is right—Head is a staggeringly authentic film in so many ways. Much of the joy of watching it lies in seeing The Monkees, unable to play anything but their teeny-bopper TV show selves, juxtaposed with legitimate, psychedelic social criticism. It is within this brilliant contradiction that the question arises: How did the era’s least authentic band create its most authentic film? And why was it so readily rejected and ignored as a false work, with no authentic merits, by the contemporary counterculture—among whom authenticity was a primary obsession?

“They were inside the wrong thing and outside the right one. This strange combination, teamed with the genuine rebelliousness and otherness of Jack Nicholson, uniquely positioned them to make the most astute criticism of their time.”

There are simple answers to these questions if we want them. Nesmith’s affinity for Nicholson and the hippie scene, paired with a studio believing that combining a cultural zeitgeist with a teen phenomenon would be financially viable, accounts for the creation of the film. Sgt. Pepper’s had been released to critical and commercial success the year before, proving that boy bands could be both psychedelic and successful. This explains much of the film’s genesis. As for the rejection of Head by the counterculture, it feels wholly logical—the only quality the counterculture valued more than authenticity was “cool,” and The Monkees, for all their possible genius, were achingly uncool. Yet these answers do not hit at the crux of the issue: that of authenticity.

Authenticity was not a problem solely for The Monkees; it was a primary concern for almost every post-war artist who tried to shape a public image that wasn’t always in line with their true selves. Regardless of where they started, most were to some extent manufactured by a team around them. The Monkees are discussed in terms of authenticity not because they were the first or only inauthentic band of the era—arguably, they were neither—but because they were among the rare few who acknowledged their own inauthenticity. Later, with Head, they acknowledged their own attempt toward authenticity.

Frank Zappa and Davy Jones in Head (1968).

At its heart, Head is a film about freedom, and the failed attempt to achieve it in a world that wants not just The Monkees, but all public figures, to be a shiny, televised version of themselves, sanitized even in their rebellion. After the opening suicide, each of the four band members kisses the same groupie and is told that they are indistinguishable from one another. They race through various genres and films, moving in unrelated vignettes as if they were aliens dropped randomly across a film studio lot. They fight in the trenches of war, ride horseback across the great American West, and solve a murder mystery in ominous, decadent housing. In each scenario, they try to prove that they are four real, individual people in a real band that makes real music that real people listen to. Yet, at every turn, they find that this pursuit is meaningless—everything they are doing is sanctioned, fated, directed, and written by the producers of the film they are trying to escape. They break the fourth wall repeatedly, intentionally flubbing lines, acknowledging actors, and referencing the flimsy walls of the set they are on—only to find that this, too, is in the script that Jack Nicholson, appearing as himself and playing his actual role as producer, wrote for them. From start to finish, it is a wild ride—a kind of Ouroboros that eats itself in its meta-reflective analysis. It digs through philosophical ideas again and again, only to find that it has dug so deep it returns on the other side, no closer to the surface than when it began—with a synthetic boy band playing their hits to an audience who don’t truly know them, and would rather keep it that way.

The film was released at the tail end of the capital-S "Sixties," before the killing at the Rolling Stones concert in Altamont turned the whole decade into a bad trip. Despite the turmoil in the world, there was still a tie-dyed, tune-in, drop-out, mind-expanding, world-changing hopefulness that believed art, youth, truth, and rebellion could really change the world. The Monkees, for most of their career, had been a distillation of this attitude—neatly packaged by executives to be sold for syndication on TV channels across the world and played relentlessly on every wavelength. They were able to operate as both insiders and outsiders, feeling less shame about their participation in the system that everyone else was pretending not to be part of. They were inside the wrong thing and outside the right one. This strange combination, teamed with the genuine rebelliousness and otherness of Jack Nicholson, uniquely positioned them to make the most astute criticism of their time. That this critique is seen to come from the most unlikely place is, perhaps, incorrect—they were the only ones who could do it so explicitly.

Head is bombastic and exaggerated, but it cuts through to something that everyone else was too scared to be honest about. The Beatles danced around the ideas on Glass Onion, Dylan nodded to them with Ballad of a Thin Man, and even Elvis, in his countless motion pictures, tried to comment on them. But all cared too much about their artistry to acknowledge that they were participating in a system they claimed to be outside of. It took The Monkees, the least cool of all, to truly speak truth to power, and they paid the price for it. In the closing minutes of the film, as the final Monkee falls to his watery death, the director wheels their soaked bodies away in a large aquarium, the band struggling as they awake, and stores it neatly on a studio lot—to be used again whenever deemed fit.

Ana Roberts is a writer, musician and culture critic.

The Hierophant (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 21, 2024

The Hierophant is the materialization of divine wisdom and power. He is the embodiment of spiritual authority. He speaks for God and gives out his edicts to the bishops, and they spread it down the hierarchy.

Name: Hierophant or Pope

Number: V

Astrology: Taurus

Qabalah: Vau

Chris Gabriel September 21, 2024

The Hierophant is the materialization of divine wisdom and power. He is the embodiment of spiritual authority. He speaks for God and gives out his edicts to the bishops, and they spread it down the hierarchy.

In Rider, we find a young pope with a false beard sitting on a throne. He is adorned in scarlet. One hand raises a staff, his papal ferula, while the other is held aloft with two fingers to God. He has an ornate papal tiara. Beside him are two pillars, and beneath him are two tonsured clergymen and the Keys of Heaven.

In Thoth, we have a statuesque Hierophant. His bearded face is a mask and he is adorned in orange. One hand raises a Borromean staff, the other points down with two fingers. He wears a simple mitre on his head and on his chest,a star with the Aeonic Child inside. Beside him are two elephants and a bull, Taurean symbols. Before him is the “woman girt with a sword” as described in Liber Al, The Book of the Law. All around him are the four elemental Cherubs, and above is a five petaled flower encircled by a serpent and 9 nails.

In Marseille, we have an old pope sitting on his throne in a scarlet cloak. Both his bare and gloved hands are marked by crosses. His gloved hand raises the papal ferula, while the other raises two fingers to God. Beneath him are two tonsured clergymen.

The Hierophant or Pope is the head of the Church. He metes out orders from God and rules through hierarchy. For each church under his rule, he ensures that they function and share his dogma.

As Taurus, this is a card concerning stubborn commitment to the set way. It is also about simplicity and comfort. In this way, fast food, soda, and comfort foods are similar to the Church. Warhol describes it well: “A coke is a coke and no amount of money can get you a better coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the cokes are the same and all the cokes are good.” This is the Hierophant, he creates a spiritual doctrine made available to all.

The Hierophant makes that possible through a set of clear methods. He oversees the structured, accessible, universal path to God. His wisdom is standardized, not ephemeral. The Magician and High Priestess are spiritual forces as well, but they don’t follow dogmas in the same way; they have direct, personal routes to the divine. The Church and the Pope, on the other hand, have a grand and strict purpose.

Through the Hierophant, we are given the invitation and rules to the tarot. The old doctrines hold the truths tighter than we’re used to. What Thoth shows freely is hidden deep within Rider and Marseille. The Hierophant is in no rush to save the world, he is comfortable patiently and diligently following the divine rules set millennia before.

When you pull the Hierophant it may be that you must utilize your knowledge, or gain help from someone wise. This can be practical knowledge and spiritual knowledge.

The Postmodern Condition

Jean-Francois Lyotard September 19, 2024

Science has always been in conflict with narratives. Judged by the yardstick of science, the majority of them prove to be fables. But to the extent that science does not restrict itself to stating useful regularities and seeks the truth, it is obliged to legitimate the rules of its own game. It then produces a discourse of legitimation with respect to its own status, a discourse called philosophy…

Roy Litchenstein, Sunrise. 1963.

Jean-Francois Lyotard, September 19th, 2024

Commissioned by the government of Quebec, Lyotard undertook a philosophical study on the affects of modern life and capitalist culture on the metaphysical health of the world. He finds an inivetability to a lack of consensus and sees differences and conflict as inherent in the modern world, yet he remains positive that postmodernism retains the modernists ideals of maintaining the hope for a new kind of social existence.

Science has always been in conflict with narratives. Judged by the yardstick of science, the majority of them prove to be fables. But to the extent that science does not restrict itself to stating useful regularities and seeks the truth, it is obliged to legitimate the rules of its own game. It then produces a discourse of legitimation with respect to its own status, a discourse called philosophy. I will use the term modern to designate any science that legitimates itself with reference to a metadiscourse of this kind making an explicit appeal to some grand narrative, such as the dialectics of Spirit, the hermeneutics of meaning, the emancipation of the rational or working subject, or the creation of wealth. For example, the rule of consensus between the sender and addressee of a statement with truth-value is deemed acceptable if it is cast in terms of a possible unanimity between rational minds: this is the Enlightenment narrative, in which the hero of knowledge works toward a good ethico-political end - universal peace. As can be seen from this example, if a metanarrative implying a philosophy of history is used to legitimate knowledge, questions are raised concerning the validity of the institutions governing the social bond: these must be legitimated as well. Thus justice is consigned to the grand narrative in the same way as truth.

Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives. This incredulity is undoubtedly a product of progress in the sciences: but that progress in turn presupposes it. To the obsolescence of the metanarrative apparatus of legitimation corresponds, most notably, the crisis of metaphysical philosophy and of the university institution which in the past relied on it. The narrative function is losing its functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal. It is being dispersed in clouds of narrative language elements - narrative, but also denotative, prescriptive, descriptive, and so on. Conveyed within each cloud are pragmatic valencies specific to its kind. Each of us lives at the intersection of many of these. However, we do not necessarily establish stable language combinations, and the properties of the ones we do establish are not necessarily communicable.

Thus the society of the future falls less within the province of a Newtonian anthropology (such as stucturalism or systems theory) than a pragmatics of language particles. There are many different language games - a heterogeneity of elements. They only give rise to institutions in patches - local determinism.

The decision makers, however, attempt to manage these clouds of sociality according to input/output matrices, following a logic which implies that their elements are commensurable and that the whole is determinable. They allocate our lives for the growth of power. In matters of social justice and of scientific truth alike, the legitimation of that power is based on its optimizing the system's performance - efficiency. The application of this criterion to all of our games necessarily entails a certain level of terror, whether soft or hard: be operational (that is, commensurable) or disappear.

The logic of maximum performance is no doubt inconsistent in many ways, particularly with respect to contradiction in the socio-economic field: it demands both less work (to lower production costs) and more (to lessen the social burden of the idle population). But our incredulity is now such that we no longer expect salvation to rise from these inconsistencies, as Marx did.

Still, the postmodern condition is as much a stranger to disenchantment as it is to the blind positivity of delegitimation. Where, after the metanarratives, can legitimacy reside? The operativity criterion is technological; it has no relevance for judging what is true or just. Is legitimacy to be found in consensus obtained through discussion, as Jurgen Habermas thinks? Such consensus does violence to the heterogeneity of language games. And invention is always born of dissension. Postmodern knowledge is not simply a tool of the authorities; it refines our sensitivity to differences and reinforces our ability to tolerate the incommensurable. Its principle is not the expert's homology, but the inventor's paralogy.

Here is the question: is a legitimation of the social bond, a just society, feasible in terms of a paradox analogous to that of scientific activity? What would such a paradox be?

Jean-Francois Lyotard (1924 –1998) was a philosopher, sociologists and literary theorist.

The New Painting

Guillaume Apollinaire September 17, 2024

The new painters have been sharply criticized for their preoccupation with geometry. And yet, geometric figures are the essence of draftsmanship. Geometry, the science that deals with space, its measurement and relationships, has always been the most basic rule of painting.

Jost Amman, Wenzel Jamnitzer. 16th Century.

Guillaume Apollinaire, September 17th, 2024

Guillaume Apollinaire was a poet, playwright, novelist, and art critic who inspired and was admired by the Cubists and Surrealists, movements that he himself coined the terms for. Here, he writes in strong defence of Cubism against the public disdain, and shows how despite the modernity of their style, they are applying ancient laws and ideas that grounds them in tradition. He draws a comparison between Euclidian Geometry and Cubism first in a series of lectures in 1911 and then put them into words here, in 1912.

The new painters have been sharply criticized for their preoccupation with geometry. And yet, geometric figures are the essence of draftsmanship. Geometry, the science that deals with space, its measurement and relationships, has always been the most basic rule of painting.

Until now, the three dimensions of Euclidean geometry sufficed to still the anxiety provoked in the souls of great artists by a sense of the infinite – anxiety that cannot be called scientific, since art and science are two separate domains.

The new painters do not intend to become geometricians, any more than their predecessors did. But it may be said that geometry is to the plastic arts what grammar is to the art of writing. Now today's scientists have gone beyond the three dimensions of Euclidean geometry. Painters have, therefore, very naturally been led to a preoccupation with those new dimensions of space that are collectively designated, in the language of modern studios, by the term fourth dimension.

Without entering into mathematical explanations pertaining to another field, and confining myself to plastic representation as I see it, I would say that in the plastic arts the fourth dimension is generated by the three known dimensions: it represents the immensity of space eternalized in all directions at a given moment. It is space itself, or the dimension of infinity; it is what gives objects plasticity. It gives them their just proportion in a given work, where as in Greek art, for example, a kind of mechanical rhythm is constantly destroying proportion.

Greek art had a purely human conception of beauty. It took man as the measure of perfection. The art of the new painters takes the infinite universe as its ideal, and it is to the fourth dimension alone that we owe this new measure of perfection that allows the artist to give objects the proportions appropriate to the degree of plasticity he wishes them to attain.

Wishing to attain the proportions of the ideal and not limiting themselves to humanity, the young painters offer us works that are more cerebral than sensual. They are moving further and further away from the old art of optical illusion and literal proportions, in order to express the grandeur of metaphysical forms.

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) was a poet, playwright, novelist and art critic.

Ten of Wands (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel September 14, 2024

The Ten of Wands is the bitter end of Fire’s descent from Heaven. It has fallen from the spiritual heights it thrives in down to the material world. This is a card of weight, labor, and responsibilities that crush the spirit…

Name: Oppression, the Ten of Wands

Number: 10

Astrology: Saturn in Sagittarius

Qabalah: Malkuth of Yod

Chris Gabriel September 14, 2024

The Ten of Wands is the bitter end of Fire’s descent from Heaven. It has fallen from the spiritual heights it thrives in down to the material world. This is a card of weight, labor, and responsibilities that crush the spirit.

In Rider, we find a man bearing ten large wands, he is bending under the weight of his heavy load. In the distance we see a town, his destination still far off.

In Thoth, two leaden wands crush the eight light blue wands beneath them. It is oppression, Saturn in Sagittarius. As with the Five of Wands, Saturn is smothering the freedom of the fire which is escaping out the sides. This is especially pronounced here, as Sagittarius demands freedom of movement. The two lead wands are modified Eastern Phurbas, ritual dagger-staffs.

In Marseille, we find a similar configuration to Thoth, though the two vertical wands are beneath the crosshatched eight. Flowers are sprouting from the sides, life from the deadened, crystallized fires. As a ten, this card symbolizes Malkuth, the Kingdom, and being Wands, it belongs to the King. Thus it is the King’s Kingdom.

This card is the material reality of hierarchical power where the lofty philosophies and justifications behind oppressive regimes and states rest on the oppression of their people. While the Five of Wands showed us a tyrannical king causing strife in his court, this card is the oppressed peasantry who live under them.

The image that arises is that of the Fasci, a bundle of sticks that are weak on their own but strong together. An ancient Roman symbol taken up by many governments throughout history, but most significantly by Mussolini and his Fascist government. The ideal of strength through unity is one thing, but the question of who is to carry that heavy bundle is another. Saturn is the oppressive state, and Sagittarius is the people. They are anathema. Sagittarius needs to move freely, and Saturn needs to restrict and stabilize to maintain its power. Revolt is inevitable.

Materially, we can see this as a fire being smothered, whether this is at the onset when one adds too much wood to a tiny fire and chokes it of oxygen, or when a fire is raging and one covers it to kill it.

This is certainly not a comfortable card. When it comes up in a reading it can indicate serious pressures, smothering responsibilities, and exhaustion. This is a card of labor, hard work. Rider shows that the destination is in view, that the toils have a clear end, but there is no such promise in Marseille and Thoth, the oppression is simply there, dull and stupid work that must be done.

We can counter this by keeping the inner fire burning and finding outlets where it can run free.

Rediscovering Living Time

Tuukka Toivonen September 12, 2024

Amid our species' many disagreements, the steady progression of time seems to be the one thing that everyone can agree upon and hold in common. The ticking of the clock offers a comforting backbeat to our daily comings and goings, promoting synchrony and order where there might otherwise be disorganization or chaos. Our eagerness to keep track of the passing of minutes and hours — as much through casual glances at our screens and other timepieces as intentional planning — is unmatched in its frequency by almost any other habit...

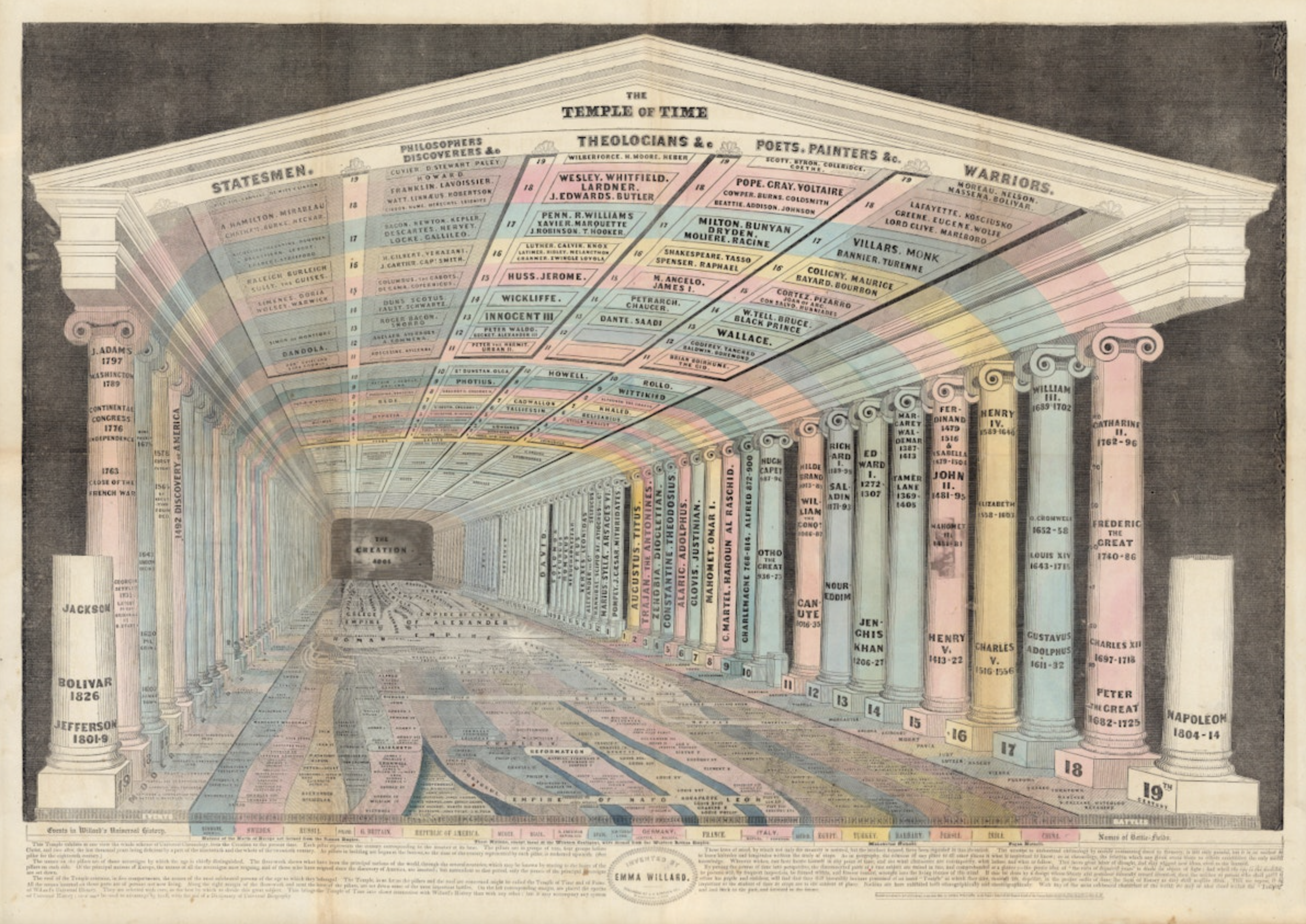

“The Temple of Time” (1846). Emma Willard.

Tuukka Toivonen September 12, 2024

Amid our species' many disagreements, the steady progression of time seems to be the one thing that everyone can agree upon and hold in common. The ticking of the clock offers a comforting backbeat to our daily comings and goings, promoting synchrony and order where there might otherwise be disorganization or chaos. Our eagerness to keep track of the passing of minutes and hours — as much through casual glances at our screens and other timepieces as intentional planning — is unmatched in its frequency by almost any other habit. There might be few moments quite as jarring as realizing one’s favored timekeeper has ground to a halt, threatening the sense of normalcy and soothing constancy afforded by clock time that our existential security seems to almost entirely rest upon. Less disorientating yet equally puzzling are the moments of flow when we become totally engrossed in soloing on the guitar, conversing with a friend or scaling up the side of a mountain, causing time as we know it to all but vanish.

Yet it is precisely these kinds of — often subtle — ruptures in one’s temporal experience that opens the door to alternative perceptions of time that can ultimately enrich our lives. Such anomalies invite active curiosity about the many mysteries and unknowns of time. Does it really progress as constantly or exist as abstractly as our attachment to machinic clock time has taught us to believe? Is time as much a co-production and outcome of life itself as it is a pace-setter? And could it be that there are cycles and makers of time that our preoccupation with the apparent precision and linearity of clock time serves to conceal? How would our lives and the way in which we partake in the more-than-human world change and expand if we explored other dimensions of time more perceptively and sensorially?

For many of us, being whisked away to a new time zone presents a type of experience that tends to fracture our sense of temporal reality quite radically — one that speaks directly to the question of how (re-)adjustment to time unfolds. We tend to normalize the sense of temporal shock by quickly adjusting our clocks to local time as soon as (or even before) we land, or by having our digital timepieces automatically adjusted for us. But our jetlagged bodies and biorhythms are not so easily persuaded, and the result is a physiological and mental sense of disorientation and fatigue at inconvenient moments. What we may not realize, however, is that the symptoms of jetlag emanate from a desynchrony of the multiple cycles we depend upon for digestion, body temperature regulation, different modes of thought, wakefulness and rest. It is therefore not the case that our acclimatization depends purely on our intentional efforts to wrestle with drowsiness — rather, it is that the complex rhythms that constitute us and the numerous symbionts we host (billions of gut microbes included) all must find a way to re-align. Restoring our “normal” sense of time and wellbeing hinges upon invisible processes through which multiple interdependent instruments — the living orchestrations of which comprise us — reach an adequate degree of synchrony and dialogue. What makes this process of readjustment truly astonishing is how it unfolds as an integrated collaboration between the vast intricacies of our biological bodies, our new environments and the way in which our home planet rotates while orbiting the sun.

As for the question of whether time marches on as precisely and exists as abstractly as we have been led to believe, exploring heliogeophysical and ecological perspectives (often neglected amid a preoccupation with physics) can help us to see a more nuanced and potent reality. First, not only do daylight hours continue to vary as the Earth travels around the sun — necessitating bodily and societal adjustments — but it actually takes the Earth slightly more than 365 days to complete one such cycle. Likewise, one rotation of the Earth on its axis does not take exactly twenty-four hours, with the Moon, earthquakes and other occurrences causing subtle fluctuations. Though imperceptible, these variations point to profound lessons about both the nature of our universe and as our own time-keeping practices and assumptions. As the historian of chronobiology and ecological restoration Mark Hall so aptly reminds us, ours is in actuality a world where “[o]rganisms do not live their lives by a metronome” but rather one where, amid constant environmental change, circadian rhythms “require continual fine-tuning” (Hall 2019, p. 385)¹. Such re-calibrations are guided by stimuli both internal and external, encompassing our solar system, our physiology as well as our social rhythms and interactions. Paradoxically enough, these multiple time-shapers that help ground our temporal experience all turn out to be far less precise and absolute than we tend to think and far more alive and idiosyncratic thanour dominant temporal cultures would imply.

“Instead of forgetting the vibrancy of living time or abandoning it in the shadow of clock time, how might you explore, and indeed celebrate, the polyphonies and polyrhythms that constitute our world and give new meaning to how time is created?”

Ecological perspectives can further enrich our understanding of time, especially if we turn to a niche group of phenologists who observe and think about the timing of diverse plant and animal species’ life-cycles. As distant as our increasingly urban and technological lives have become from the vibrant more-than-human world, most of us still retain some attachment to seasonal changes and an appreciation for their enmeshment with natural life. We intuitively realize that the appearance of swallows and other migratory birds in the Northern Hemisphere is a sign of spring (just as their return to lands in the Southern Hemisphere is taken as a sign of spring or early summer there). The blooming of certain flowers — and the simultaneous appearance of pollinators — likewise stimulates oursense of the seasons changing. The same is true of loud choruses of cicadas becoming replaced with the chirping of crickets as summer turns into autumn in places such as Japan. What phenologists have done is to bring a systematic approach to such observations of life’s cycles and developed a more refined understanding of how the rhythms of different organisms interact. For instance, flowering timings have most probably evolved with pollinators while the leaves on the same plants seem to time their cycles in relation to the herbivores that consume them. Scholars such as Bastian and Bayliss² have also brought attention to the immense value of traditional and indigenous phenological knowledges, such as calendars attuned to highly localized patterns of plant and animal life. The beauty of such calendars — that include the Japanese shi-ju-ni-ko calendar that tracks not four but forty-two seasons — is that they help bring about a sense of integration between human communities and more-than-human ecologies.

“Picture of Nations; or Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire”, (1836). Emma Willard.