Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941498045?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Alexander Calder performs his circus"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

A Brief History of White Magic, Part 1.

Flora Knight June 4, 2024

The history of White Magic is the history of a middle way, and the history of harnessed imagination. Different from ‘Black Magic’, which is magic with the intention of harm or wrongdoing, White Magic is about transcendence, knowledge, self-improvement and the betterment of the world…

A medieval illustration of a magic circle, showing the middle way.

Flora Knight June 4, 2024

The history of White Magic is the history of a middle way, and the history of harnessed imagination. Different from ‘Black Magic’, which is magic with the intention of harm or wrongdoing, White Magic is about transcendence, knowledge, self-improvement and the betterment of the world. The very word "magi", from which our “magic” comes, is a Persian word for the learned class. White Magic is both high art and science, concerned with releasing the powers of imagination through a practiced harmony with the universe.

It begins in our earliest records and continues through to modernity. To fully understand it, we must see it as one of the three governing schools of thought that have existed since early civilisation, alongside science and religion. It is both a separate pursuit and a synthesis of these two, a middle way. The distinctions between these three schools can be best understood as:

1. In religion, one requests manipulation of the created universe by God or his agents.

2. In science, one manipulates parts of the created universe oneself.

3. In magic, one manipulates parts of the created universe with non-physical agencies.

In the ancient world, all three approaches were legitimate. In medieval times, religion was the only way forward, and dabbling in science and magic was considered impious. Today, in modernity, science has become the accepted way to understand the world, with increasingly less space for religion or magic. The magical mind understands magic as the link and reconciliation between science and religion, without condemning either.

It is ultimately difficult to disentangle these three threads across history for they have lived in a constant state of dialogue. Magic is ultimately a continuation of pre-Christian pagan ritual and Neo-Platonic thought—the earliest ideas of science and religion. While these two progressed and changed, magic at its core remained remarkably consistent. Nonetheless, its history reveals its subtleties.

I. Antiquity

The ancient world, in this case Egypt, Rome, and Greece, laid the foundations for all magic that followed. The distinctions in this era are less clear. Paganism and polytheism ruled, and magic was a part of daily life. The traditions and ideas that developed here informed all magic and witchcraft that followed. These cultures took from one another, and this interchange allowed for pagan tolerance, paganism at this time simply meaning the practicing of a religion outside of the ‘mainstream’, where Gods from each culture were absorbed into the others.

For the history of white magic, the most important pagan god is Thoth, also known, in Rome and Greece, as Hermes and Mercury respectively. Thoth is the god of magic, the moon, trade, learning, and books. Egyptian writing attributed to Thoth laid the foundations for all European magic that followed and Jewish influence in Egypt also helped create these base principles. It was during this time that an important distinction was made: that of the difference between theurgy and thaumaturgy, or high and low magic, respectively. Theurgy is the raising of consciousness above the material world to the realization of a restored world. Thaumaturgy, or sorcery, is the production of wonders by the powers of the mind. In the Jewish story of Aaron and Moses against the Pharaoh’s magicians, the men duelled each other by transforming rods into serpents. This was an act of Thaumaturgy and there is a close relationship between this form of magic and the religious ideas of miracles.

Stories and symbols from this era pervade the history of witchcraft and white magic. The Egyptian funerary rites, administered by Thoth, created the idea of ‘secret passwords’ or cryptic spells. The use of wax figurines, or voodoo dolls, also came from this process. Farming practices led to the idea of a guiding star, which was later adopted by Christianity and Masonic symbolism. In the world of ancient Egypt, the distinctions mentioned meant little; magic was intertwined with religion and science and all three combined as a way to understand the world.

A layout of the interior chambers of the Temple of Solomon.

Around 950BC, The Temple of Solomon was built in the then Egyptian city of Jerusalem. It is the most important physical site of magic, laying the building blocks of not just magical architecture but also sacred geometry and the conception of the magical universe as a whole. It was built to house the Ark of the Covenant and is the earliest forerunner of pagan mystery religions—a way of combining magic, paganism, and spirituality with mainstream religion. We see its influence in Templar magic, the Freemasons, and in the rise of ‘magic spell books,’ one of the most important in Renaissance magic being the ‘Clavicle of Solomon.’

II. Early Christianity

As Christianity spread across the world, four threads emerged that play a vital role in the history of white magic and witchcraft. These are Gnosticism, Hermetic literature, Neo-Platonic philosophy, and the Jewish Qabalah. Gnosticism was the amalgamation of pagan magic and Christianity. Hermetic literature reflected the Christian impact on Greek philosophy and Egyptian magic. Neo-Platonic philosophy was the resurgence of Greek thinking, and Jewish Qabalah was a form of Jewish mysticism. All four of these threads are essential to the conception of witchcraft, and there is endless scholarship on all of them. It is Hermetic literature and Qabalah, however, that have remained the most potent influence on modern witch-cults, the Golden Dawn, and Wicca itself.

A representation of the Qabalah Cube.

Qabalah didn’t flourish in its entirety until the Renaissance, but in the days of early Christianity, many of its ideas were conceived. In a brief history, the most encompassing for us is the Qabalistic Cube as a representation of the universe. The Qabalah was a break from Christian thinking, placing transcendence and introspection as its core tenets. The Cube was a representation of the universe that mirrored man's consciousness, a tree of life that placed all existence along a single thread. It was an early example, along with the Temple of Solomon, of a portrayed fourfold universe—an important number and conception in all later witchcraft. It also represented the twelve zodiac signs and assigned them characteristics, with mental activity represented by Mercury, love by Venus, order by Jupiter, and inspiration by the Sun. The Qabalah Cube consists of ten interconnected spheres, or sephiroth, representing different aspects of divine emanation and the journey of the soul. Each sphere embodies spiritual principles and cosmic forces, which together form a multidimensional map of existence. It is a tool for understanding the interconnectedness of the universe, the divine hierarchy, and symbolizes the eternal quest for unity and harmony within the cosmos. Through meditation and study of its intricate pathways, practitioners seek spiritual enlightenment and alignment with the divine will.

Hermetic literature is another important development of this era. These works took the form of compilations of allegedly ancient texts, attributed to an amalgamation of Thoth and Hermes. The most relevant is the Cyranides: put together in the 4th century, it is one of the earliest magic spell books, pertaining to mystic remedies, spells, and the practical and magical properties of plants, animals, and amulets. There were a whole host of Hermetic texts related to these properties, as well as groundwork for astrology and the foundations of alchemy. These texts are almost all lost and exist only in fragments, but their influence on witchcraft is paramount.

For the first thousand years of its recorded existence, white magic was a central way of understanding the world. It was not altogether a distinct path, but a necessary strand of thinking that informed and complimented religious and scientific thought. In these periods, each new culture and civilisation imbued it with their own mythology, ideas and conceptions and it adapted these disparate influences into a unique way of thinking which pervaded across the world. As Christianity began to spread, the magical way was forced underground, taking with it a millennia of hidden and forbidden knowledge.

Flora Knight is an occultist and historian.

Tyler Cowen Playlist

Music on the Other Side

I don’t like the term “world music” — isn’t all music “world music”? But until aliens visit us, this will have to do. These are from various popular music traditions, with broadly African and African-American emphases.

Tyler Cowen June 3, 2024

I don’t like the term “world music” — isn’t all music “world music”? But until aliens visit us, this will have to do. These are from various popular music traditions, with broadly African and African-American emphases.

Tyler Cowen is Holbert L. Harris Chair of Economics at George Mason University and serves as chairman and general director of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. With colleague Alex Tabarrok, Cowen is coauthor of the popular economics blog Marginal Revolution and cofounder of the online educational platform Marginal Revolution University.

The Knight of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel June 1, 2024

The Knight of Cups is a court card and the highest card in the suit of Cups. In each iteration we find a bluish gray horse, mounted by a fair haired rider bearing a cup. This is a card of confusion and desire…

Name: Knight of Cups

Astrology: Pisces, Fire of Water

Qabalah: Yod of He י of ה

Chris Gabriel June 1, 2024

The Knight of Cups is a court card and the highest card in the suit of Cups. In each iteration we find a bluish gray horse, mounted by a fair haired rider bearing a cup. This is a card of confusion and desire.

In Marseille, we find a rather plain rider, lacking the armor of the other two cards. He is smiling, holding a large golden cup with red detail. His horse appears satisfied. Both he and his horse have blonde hair.

In Rider, we find a much more determined figure, bearing a stern demeanor and firm grasp of his cup. He has a winged helmet, armor, and a tunic decorated with fish. His shoes are winged. His horse seems to hesitate as they prepare to cross a river and approach a mountain range.

In Thoth, we see a figure in the midst of great activity, his horse galloping ahead. He has dark armor and two large wings. His cup holds a crab, even though he is the image of Pisces. He is surrounded by waves, and beneath him is a peacock.

The image Rider and Thoth evoke to me is that of the Flying Fish, who leaps from his home in the sea to surf the waves with his fins. And just as the saying goes, the Knight of Cups is a “fish out of water”. He is Pisces as Flying Fish. His Knightly nature is that of Fire, but his suit is Water, meaning there is fundamental conflict; He is the Fish who fights against his own needs.

As such, we find the flying fish’s human correlation in the Surfer. One who leaves the land to dominate and harness the water. This is the nature of the Knight of Cups, surfing the power of the ocean, but never far from drowning.

Flying Fish, Kristen Middleton

Symbolically, we see this as the archetypal Grail Knight, the knight not only seeking the cup, but seeking to be worthy of the cup. The Grail Knight must have an absolutely pure and perfect Heart to be worthy of the Grail, but this is exceedingly rare, for the pure heart exists in opposition to our base drives. Like fire and water they combat each other. In the Grail stories this leads to terrible failure, with a character like Klingsor going as far as to castrate himself in an attempt to be pure enough for the Grail.

Thus this card is characterized by confusion and conflict. There is the overwhelming desire to obtain the Grail, to surf larger and larger waves, but it is always met equally by Nature, and it’s bestial demands to crawl in the dust of the Earth.

When dealt this card, we may be confronted with our own confused desires, or with a figure who embodies this conflict, it may even be as simple as a Pisces that we know.

Hannah Peel Playlist

Archival - July 17, 2024

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941492687?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Carl Sagan testifying before congress in 1985 on climate change"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

The Poetic Diary of Ramuntcho Matta (Excerpt II)

Ramuntcho Matta May 30, 2024

How to become a better me?

But first, what do you call me? How do you call me? There are no special lines, no direct lines. There are only paths mades of confusions, pains and distraught. Paths mades of encounters, dances and sleeps…

Ramuntcho Matta May 30, 2024

I.

How to become a better me?

But first, what do you call me? How do you call me? There are no special lines, no direct lines. There are only paths mades of confusions, pains and distraught. Paths mades of encounters, dances and sleeps.

In the South of France there is a land that does not want to be a country. The people there do not want borders. Are there borders anyway?

I am here with a Basque cake, I sit on a bench and they come, all dressed in white, in red and strange hats.

All dressed in white?

It reminds me a song,

All dressed in black?

They come and they dance, each village has their own version. Does your body remember the dance? It does but you can’t recall.

Basque Identity is a moving cross, a representation of the four elements. But we know we have five elements. We have five fingers because we are five elements.

Every day, I will practice my five elements. Water > earth > wood > metal > fire. 3 times, sometimes more. This is the first exercise. At the beginning you will feel very little but after a few weeks you will start to enter in a new dimension and after 4 years you will be water, earth, wood, metal and fire.

You already have this in you but you are not trained to feed yourselves with those sensations.

II.

As a child becomes a flower when they see a flower…

you have to be water that becomes earth,

earth that becomes wood,

wood that becomes metal,

metal that becomes fire,

fire that becomes water,

water that becomes…

That becoming is the essence of being.

Being an animal,

being a human,

being a chair,

a nice meal,

an old stone.

The other day I was invited to present my drawings. In my life of brushstrokes, sometimes words show up. Where they come from is not relevant, where they drive me… that’s the point.

I started to play with my guitar and a dog showed up, so i wanted him to sing, and here we are, a dog’s song… the blues of a dog.

What is “me“ for a dog ? What is his “self“, his “I“? What is the balance between “I“ and “me“ that could make a better “self“?

A dog does not care about this because he does not care about knowing more: instead, he feels more. Much more.

I remember the song.

All dressed in black,

walking the dog,

being a dog…

III.

I can show you how to enter into that dimension. There are exercises and practices but if you are not ready it will be useless. Brion Gysin and Bill Burroughs wanted to create a school but very soon they felt that this kind of knowledge is not for everybody. So transmission should be more maieutics.

Back to the drawing: you see the triangle… “me“ is the body. “I“ the mind. How much of your body is your self? How much of your mind?

Do you mind?

Do you body?

“I don’t mind“,

What a curious sentence.

The rhythm of the phrases is at least as important as the meaning of the words. This is what Bill used to say.

Now you can feel more,

Feeling is not a knowledge

It is a dimension of being.

Ramuntcho Matta is a producer, sound designer and visual artist.

Robert Downey Jr.

2hr 19m

5.28.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with Robert Downey Jr. about the interplay between actors.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/xiwi2xdr/widget?token=1c1c08f443098bccd120651ce70adcf3" frameborder="0"></iframe>

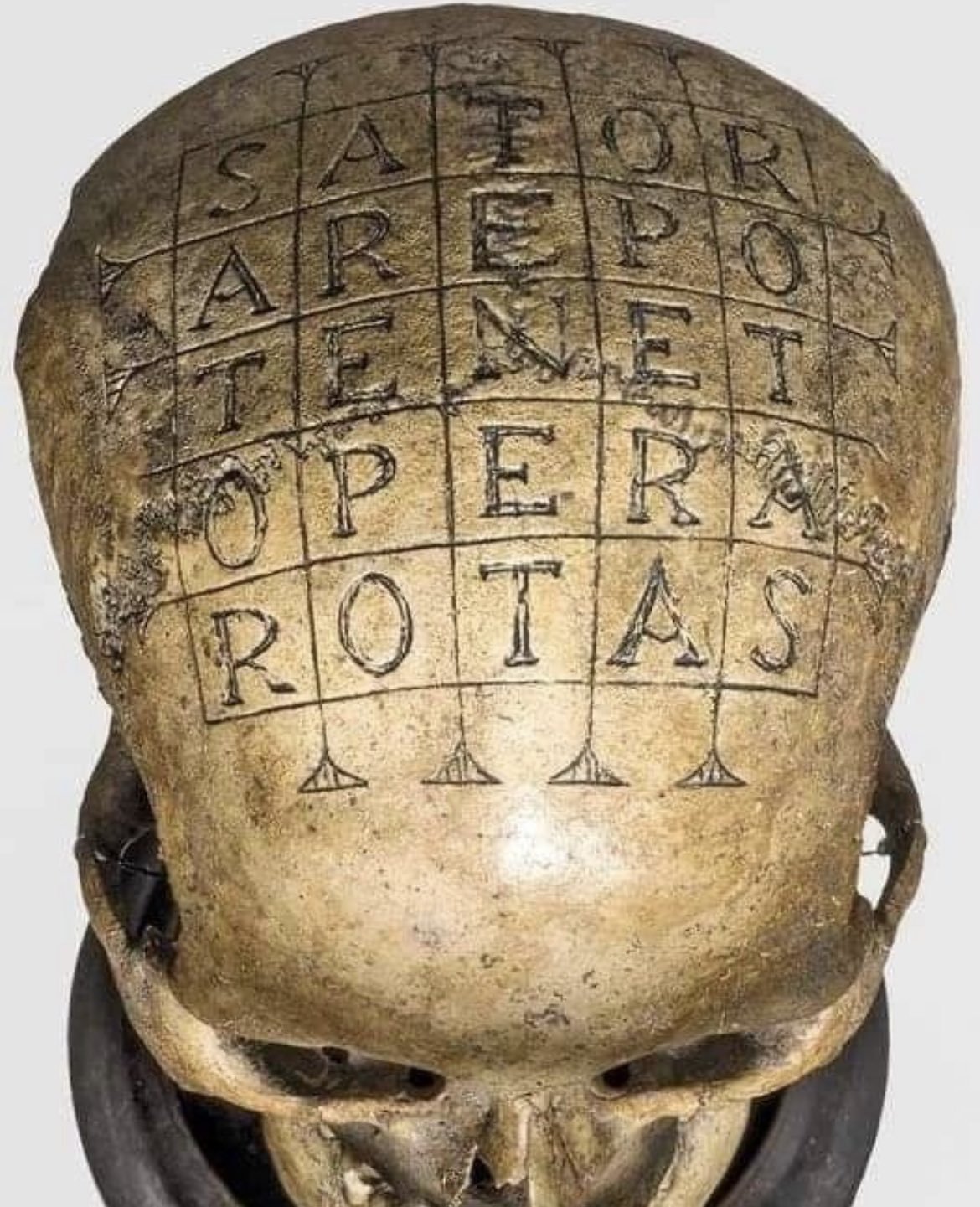

Sator Squares (Artefact III)

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies…

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 3

Location: Across Europe and the Americas.

Age: 2000 years

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies.

Sator Square in the village of Oppède le Vieux.

The “it” in question is the Sator Square. A Latin, five-line palindrome, it can be read from left or right, upwards or downwards. The earliest ones occur at Roman sites throughout the empire and by the Middle Ages, they had spread across northern Europe and were used as magical symbols to cure, prevent, and sometimes play a role in all sorts of wickedness. The one pictured here is set in the doorway of a medieval house in the semi-ruined village of Oppède le Vieux, Provence, France, carved to ward off evil spirits.

There are several different translations of the Latin, depending on how the square is read. Here is a simple version to get us started:

AREPO is taken to be a proper name, so, AREPO, SATOR (the gardener/ sower), TENET (holds), OPERA (works), ROTAS (the wheels/plow), which could come out something like ‘Arepo the gardener holds and works the wheels/plow’. Other similar translations include ‘The farmer Arepo works his wheels’ or ‘The sower Arepo guides the plow with care’.

Some academics insist that the square is read in a boustrophedon style, meaning ‘as the ox plows’, which is to say reading one line forwards and the next line backwards, as a farmer would work a field. Such a method would not only emphasize the agricultural nature of the square but also allow a more lyrical reading and could be very loosely translated thus: “as ye sow, so shall ye reap.”

“Early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stated that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.”

Sator Square with A O in chi format.

There are multiple translations and theories surrounding Sator Squares. They became the focus for intense academic debate about 150 years ago. Most of the early studies assumed that they were Christian in origin. The earliest known examples at that time appeared on 6th and 7th century Christian manuscripts and focussed on the Paternoster anagram contained within: by rearranging the letters, the Sator Square spells out Paternoster or ‘our father’, with the leftover A and O symbolizing the Alpha and the Omega.

However, in the 1920s and 30s, two Sator Squares were discovered within the ruins of Pompeii. The fatal eruption of Vesuvius that buried the city occurred in AD 79, and it is very unlikely that there were any Christians there so soon after Christ’s death. But the city did have a large Jewish community, and many contemporary scholars see the Jewish Tau symbol in the TENET cross of the palindrome, as well as other Talmudic references across the square, as proof of its Jewish origins. Pompeii’s Jews faced pogroms throughout their history, and it makes sense that they might try to hide an expression of their faith within a Roman word puzzle.

Sator Squares spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and appear in the margins of Christian manuscripts, in important treatises on magic, and in a medical book as a cure for dog-bites. Over time, they gained popularity amongst the poor as a folk remedy, even amongst those who had no knowledge of Latin or were even illiterate. (Being ignorant of meaning might increase the potency of the magic by concealing the essential gibberish of the script). In 16th century Lyon, France, a person was reportedly cured of insanity after eating three crusts of bread with the Sator Square written on them.

As the square traveled across time and country, nowhere was it used more enthusiastically than in Germany and parts of the Low Countries, where the words were etched onto wooden plates and thrown into fires to extinguish them. There are early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stating that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.

Oath Skull with Sator Square carved into bone.

From the same period comes a more sinister use of the square: The Oath Skull. Discovered in Münster in 2015 it is a human skull engraved with the Sator Square and radiocarbon dated between the 15th and 16th Centuries. It is believed to have been used by the Vedic Courts, a shadowy and ruthless court system that operated in Westphalia during that time. All proceedings of the courts were secret, even the names of judges were withheld, and death sentences were carried out by assassination or lynching. One of the few ways the accused could clear their names was by swearing an oath. Vedic courts used Oath Skulls as a means of underscoring the life-or-death nature of proceedings, and it is thought that the inclusion of the Sator Square on this skull added another level of mysticism - and the threat of eternal damnation - to the oath ritual.

When the poor of Europe headed for the New World, they took their beliefs with them. Sator Squares were used in the Americas until the late 19th century to treat snake bites, fight fires, and prevent miscarriages.

For 2000 years, interest in the Sator Squares has not waned, and a new generation has been exposed to them through the release of Christopher Nolan’s film TENET, named after the square. The film, about people who can move forwards and backwards in time, makes other references too: ‘Sator’ is the name of the arch villain played by Kenneth Branagh; ‘Arepo’ is the name of another character, a Spanish art forger whose paintings are kept in a vault protected by ‘Rotas Security’. In the film, ‘Tenet’ is the name of the intelligence agency that is fighting to keep the world from a temporal Armageddon.

Sator Squares have been described as history’s first meme. They have outlasted empires and nations, spreading across the western world and taking on newfound significance to each civilization that adopts them. Arepo should be proud of his work.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

Film

<div style="padding:41.67% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941483167?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The Naked Youth clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - May 8, 2015

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

The Four of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 25, 2024

The Four of Swords is air, at a point of stillness and equilibrium. This is a card of calm, and of temporary resolution to internal problems…

Name: Truce

Number: 4

Astrology: Jupiter in Libra

Qabalah: Chesed of Vau ו

Chris Gabriel May 25, 2024

The Four of Swords is air, at a point of stillness and equilibrium. This is a card of calm, and of temporary resolution to internal problems.

In Rider, we see a Gisant, or a tomb effigy. A young man depicted at rest, his image forever in prayer. His tomb bears a sword, and above him are the other three. In the top left corner, a stained glass window depicts a priest giving rites to a kneeling person.

In Thoth, we see four swords aimed at the center of a flower, forming a cross. We have the purple of Jupiter and the green of Libra. This is an expansive peace, a magnanimous truce. It calls to mind the Christmas Truce of World War 1 - out of jollity and a higher spirituality came temporary peace and mutual joy.

In Marseille, we have four arched swords and a central flower. Through Qabalah, we arrive at the Chesed of Vau, or the Mercy of Prince. The Mercy of the Prince is a Truce.

In this card we see beautiful but fragile rest, the violence of the suit brought to a brief standstill out of reverence to a higher force. This is a family dinner with differences put aside, a holiday party when bitter relatives agree to keep the peace for the sake of the season. There is something “higher” calling us to pause personal conflicts, whether it’s the religiosity and “goodwill” of a holiday, or the wellbeing of children and family. This is precisely the realm of Jupiter, that mercy and joy that beneficently orders conflict to cease for a moment.

This is in no way a solution, and may very well devolve into conflict if not carefully maintained, but it is a respite. We also see a serious divide in spiritual outlook between Rider and Thoth, when four, the stable number, is applied to swords. Is stability only truly attained in the grave? Or can a brief armistice give us the same thing?

Hamlet, yearning for peace, declares death the only end to heartache and the thousand natural shocks, but even then, the fear that this rest is illusion pervades his mind.

When dealt this card, we are being offered a temporary resolution, either to the internal conflicts within our restless minds, or the disagreements we have with those around us. Keep the truce, appreciate the respite, but prepare for things to break down, and quickly!

Questlove Playlist

WrdAlYnckvc

Archival - May Evening, 2024

Questlove has been the drummer and co-frontman for the original all-live, all-the-time Grammy Award-winning hip-hop group The Roots since 1987. Questlove is also a music history professor, a best-selling author and the Academy Award-winning director of the 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/942461068?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The Ranting of an Independent Filmmaker clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

The Power of Regret

Claudia Cockerell May 23, 2024

In the winter of 1981, a 22-year-old Texan called Bruce was on a train through Europe. A girl boarded at Paris and sat down next to him. They started chatting, and it felt like they’d known each other their whole lives. After a while they were holding hands. When it came to her stop they parted ways with a kiss. They never traded numbers, and Bruce didn’t even know her surname. “I never saw her again, and I’ve always wished I stepped off that train,” he wrote, 40 years on, in his submission to The World Regret Survey.

Melancholy, 1891. Edvard Munch.

Claudia Cockerell May 23, 2024

In the winter of 1981, a 22-year-old Texan called Bruce was on a train through Europe. A girl boarded at Paris and sat down next to him. They started chatting, and it felt like they’d known each other their whole lives. After a while they were holding hands. When it came to her stop they parted ways with a kiss. They never traded numbers, and Bruce didn’t even know her surname. “I never saw her again, and I’ve always wished I stepped off that train,” he wrote, 40 years on, in his submission to The World Regret Survey.

It’s a website you should visit if you ever need some perspective. Set up by author Daniel Pink, it asked thousands of people from hundreds of countries to anonymously share their biggest regrets in life. It’s strangely intimate, delving into the things people wish they’d done, or not done at all, and the answers run the gamut of the human condition.

For all the people who regret cheating on their partners, there are just as many who wish they’d never married them in the first place. One 66-year-old man in Florida regrets “being too promiscuous,” while a 17-year-old in Massachusetts says “I wish I asked out the girls I was interested in.” The stories range from quotidian (“When I was 13 I quit the saxophone because I thought it was too uncool to keep playing”) to tragic (“Not taking my grandmother candy on her deathbed. She specifically requested it”).

Sometimes we feel schadenfreude when reading about other people’s failings, but there’s something about regret that is pathos-filled and painfully relatable. Flicking through the answers, many of people’s biggest regrets are the things they didn’t do. We fantasise about what could have been if only we’d moved countries, switched jobs, taken more risks, or told someone we loved them.

“It just wasn’t meant to be. I still long for the sea - and to be near the waves”.

Pink wrote a book about his findings, called The Power of Regret. “We’re built to seek pleasure and to avoid pain - to prefer chocolate cupcakes to caterpillar smoothies and sex with our partner to an audit with the tax man”, he states. Why then, do we use our regrets to self-flagellate, more often wondering “if only…” rather than comforting ourselves with “at least”?

“One of the biggest regrets I have is not moving to California after graduating college. Instead I stayed in the midwest, married a girl, and ended up getting divorced because it just wasn't meant to be. I still long for the sea - and to be near the waves,” writes one man in Nebraska. This pining reflects the rose tinted lens through which we look at what could have been. California with its rolling waves and sandy beaches is synonymous with a life of freedom, love, and joy.

Studland Beach, 1912. Vanessa Bell.

Instead of categorising regrets by whether they are work, money, or romance related, Pink has created a new system, arguing that regrets fall into four core categories: foundation, moral, boldness and connection regrets. Within these groups, there are regrets of the things we did do (often moral), and things we didn’t do (often connection and boldness regrets). The things we didn’t do are frequently more painful because, as Pink says, ‘inactions, by laying eggs under our skin, incubate endless speculation’. So you’re better off setting up that business, or asking that girl out, or stepping off the train, because of the inherently limited nature of contemplating action versus inaction.

The actions which we do end up regretting are often moral failings that fall under the umbrella of a ten commandments breach. As well as adultery, larceny and the like, there’s poignant memories of childhood cruelty. A 56-year-old woman in Kansas still beats herself up about something she did 45 years earlier: “Throwing rocks at my former best friend in 6th grade as she walked home from school. I was walking behind her with my “new” friends. Terrible.”

But regrets can have a galvanising effect, if we choose to let them. Instead of wallowing in the sadness of wishing we could rewind time, or take back something horrible we said or did, we can use that angsty feeling as an impetus for change. “When regret smothers, it can weigh us down. But when it pokes, it can lift us up,” says Pink. There’s an old proverb which has probably been cross-stitched earnestly onto many a cushion, but I still like it as a mantra for overcoming pangs of regret: “The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second-best time is today.”

Claudia Cockerell is a journalist and classicist.

Tom O’Neill

2hr 45m

5.22.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with ‘CHAOS’ author Tom O’Neill about the mystery of Charles Manson’s magnetic persona.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/fwiyxjwa/widget?token=3ce0e3b91ac2095d250fc664df72fa2f" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Grasping at Gesture

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

Hand Catching Lead, 1968. Richard Serra.

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

In the first of these texts on gesture, I traced an unreliable and partial history of hand gestures – from roman orators and Martine Syms, to teens on TikTok and TikToks of tech bros using Apple Vision Pro – and how, somewhere along the way we lost our gestures, or lost control of them; gesticulating wildly in the open air.

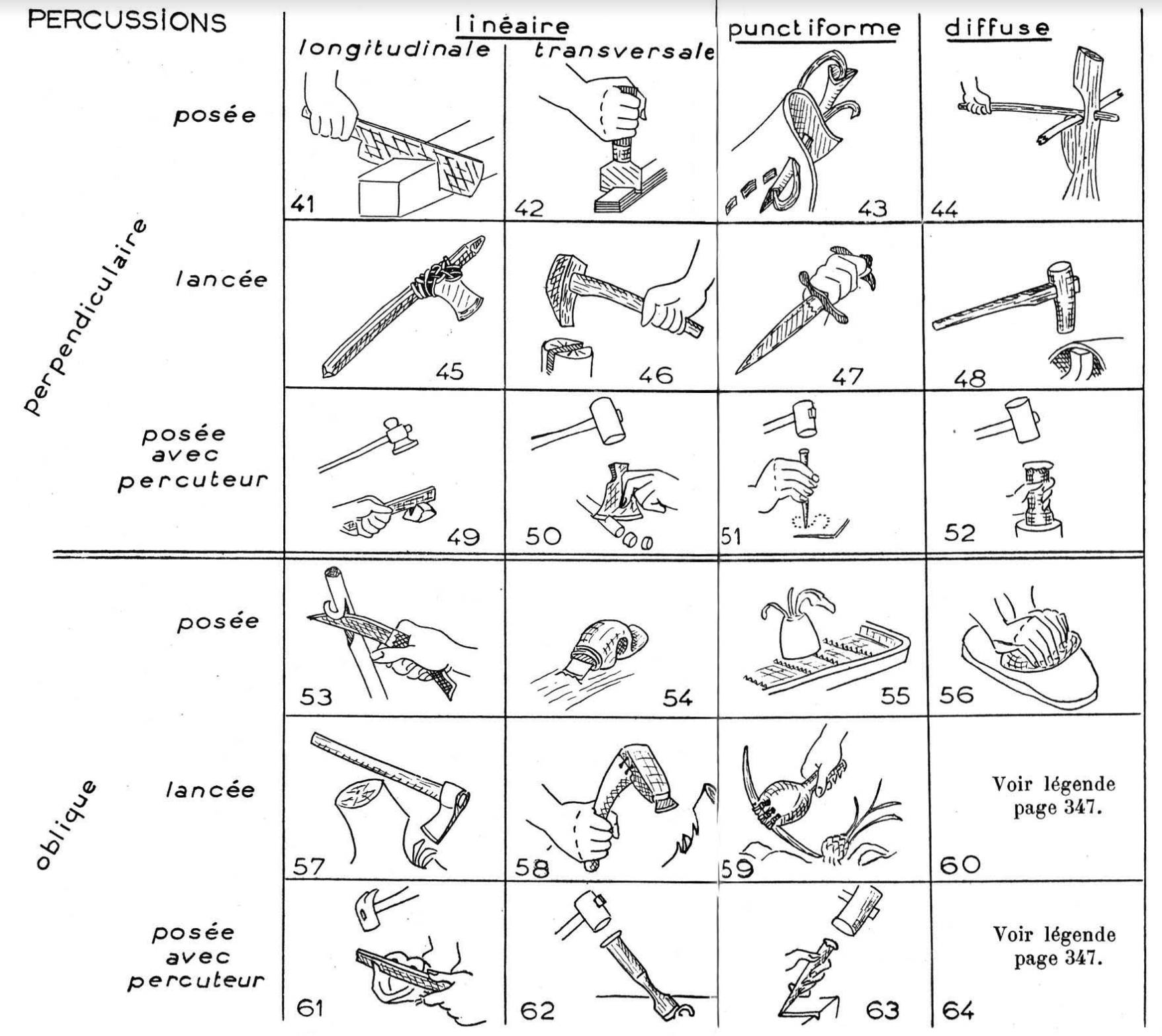

Man and Matter, 1943. Leroi-Gourhan.

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

‘The essential traits of human technical gesticulation are undoubtedly connected with grasping’¹ said Andre Leroi-Gourhan in his 1965 book, Gesture and Speech. A pioneering anthropologist, Leroi-Gourhan traced evolving relationships between hands, tools, gestures, languages, and thoughts, and developed a corresponding science for such. He is associated with Structuralist school, which means that he sought out the underlying processes (or structures) that make systems meaningful. Leroi-Gourhan’s Gesture and Speech does many things: It traces a bio-cultural evolution of postures, hands, brains, tools, art and language, up to the present day; conducts cross-cultural analysis of the rhythms and organization of human society, value systems, social behavior and techno-economic apparatus; and, amidst nascent developments in robotics and early experiments in automation, speculates on the future of our species.

“Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot.”

Alcuni Monumenti del Museo Carrafa, 1778.

The book begins with a history of the human brain and hand, with Leroi-Gourhan explaining: ‘it seemed to me that the first thing to do was to measure the results of what can be done with the hand to see what [our]brains can think.’² In pursuing both brain and hand he opposed the prevailing approach in evolution studies to focus only on the ‘cerebral’. Leroi-Gourhan was interested in how thought is embodied, how it springs from material conditions.

So, what can be done with the hand? Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot; they could grip and grasp and gesture. Now grasping is not specific to humans – qualitatively, the hand that grasps remains a relatively rudimentary device that's accompanied us across many evolutionary stages – and there are a variety of types and properties of grasps. Studying the transition from instinctive to cultural uses of hands, Leroi-Gourhan observed the functional shift from the mouth to the hand, from the hand to the grasped tool, and finally the hand that operates the machine. When it comes to grasping, ‘the actions of the teeth shift to the hand, which handles the portable tool; then the tool shifts still further away, and a part of the gesture is transferred from the arm to the hand-operated machine’. This he describes as a gradual exteriorization, or ‘secretion’ of the hand-and-brain into the tool.

But gesture still somewhat eludes us, its location ambiguous. Gesture is not in and of the hand, nor in and of the tool, rather gesture is the meeting of brain, hand and tool, the driving force and thought that sets the tool to action. To bring these gestures to light, Leroi-Gourhan developed the methodology for which he is best known: the Chaîne Opératoire.

The Chaîne Opératoire, or operational chain, is a method that makes processes visible by documenting the sequence of techniques that bring things into being – be they tangible artifacts, ephemeral performances, or even the acquisition of intangible status. Leroi-Gourhan described a technique as ‘made of both gesture and tool, organized in a chain by a true syntax’. The use of ‘syntax’ here (Structuralists had a thing for linguistics) establishes a relationship between the processes and the performance of language where there is room for both shared meaning and individual flourishes. Here, gesture, like the arrangement of words in a sentence, is relational, acquiring its shape and meaning through the interaction of mind, body, tool, material and social worlds in which it participates.

This whole time thinking about grasping hands I’ve had a film in mind: Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead, in which morsels of lead fall from above, are caught, and then released by the artist's hand. Far from mechanically consistent, sometimes Serra grasps the object, sometimes he grasps at it, narrowing missing and smacking fingers to palm. From 1968 into the early 70s Serra made a series of other hand films whose subject matter are just as the titles suggest: in Hand Catching Lead a hand, of course, catches lead; in Hands Scraping (1968) two pairs of hands gather up lead shavings which have accumulated on the floor/filled the frame; in Hands Tied two tied-uphands untie themselves.

“The creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool.. can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties.”

Hands Scraping, 1968. Richard Serra.

Curator Søren Grammel said Serra’s hand works ‘demonstrate a particular action that can be applied to a material’. I suppose that’s what the Chaîne Opératoire gets at too, as well as demonstrating how the material acts on us; in Hand Catching Lead, the lead rubs off onto Serra’s blackened hands. And just as the Chaîne Opératoire observes the network of gestures that fulfill an operation, the duration of Serra’s films cosplay pragmatism, lasting as long as it takes to complete the task (however arbitrary): How many pieces of lead can you catch or not catch until you are exhausted/cramp-up/are no longer interested? How long does it take to sweep up lead shavings or untie a knot?

Serra’s Hand Catching Lead was prompted in part by being asked to document the making of House of Cards (a sculpture where four large lead sheets are propped against one another to form the sides of a cube). But a film following the making process would, he felt, be too literal and merely illustrative. Instead, Hand Catching Lead is a ‘filmic analogy’ of the creative process. Serra knew that the creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool like the Chaîne Opératoire can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties. It seems we have come up against the limits of this approach, and of Structuralism's commitment to linguistics. Returning to Agamben, who we met in the first text: ‘being-in-language is not something that could be said in sentences, the gesture is essentially always a gesture of not being able to figure something out in language; it is always a gag in the proper meaning of the term…’³ Perhaps then Serra’s grasps are gags, grasping at lead, at air and at the irrepresentable nature of being-in-gesture.

¹ Andre Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1993) [1965]), 238

² ibid.,146

³ Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000) 59

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer, researcher and editor. She is the co-founding editor of motor dance journal.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941497753?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The biggest difference between bad art and great art"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>