Sator Squares (Artefact III)

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies…

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 3

Location: Across Europe and the Americas.

Age: 2000 years

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies.

Sator Square in the village of Oppède le Vieux.

The “it” in question is the Sator Square. A Latin, five-line palindrome, it can be read from left or right, upwards or downwards. The earliest ones occur at Roman sites throughout the empire and by the Middle Ages, they had spread across northern Europe and were used as magical symbols to cure, prevent, and sometimes play a role in all sorts of wickedness. The one pictured here is set in the doorway of a medieval house in the semi-ruined village of Oppède le Vieux, Provence, France, carved to ward off evil spirits.

There are several different translations of the Latin, depending on how the square is read. Here is a simple version to get us started:

AREPO is taken to be a proper name, so, AREPO, SATOR (the gardener/ sower), TENET (holds), OPERA (works), ROTAS (the wheels/plow), which could come out something like ‘Arepo the gardener holds and works the wheels/plow’. Other similar translations include ‘The farmer Arepo works his wheels’ or ‘The sower Arepo guides the plow with care’.

Some academics insist that the square is read in a boustrophedon style, meaning ‘as the ox plows’, which is to say reading one line forwards and the next line backwards, as a farmer would work a field. Such a method would not only emphasize the agricultural nature of the square but also allow a more lyrical reading and could be very loosely translated thus: “as ye sow, so shall ye reap.”

“Early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stated that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.”

Sator Square with A O in chi format.

There are multiple translations and theories surrounding Sator Squares. They became the focus for intense academic debate about 150 years ago. Most of the early studies assumed that they were Christian in origin. The earliest known examples at that time appeared on 6th and 7th century Christian manuscripts and focussed on the Paternoster anagram contained within: by rearranging the letters, the Sator Square spells out Paternoster or ‘our father’, with the leftover A and O symbolizing the Alpha and the Omega.

However, in the 1920s and 30s, two Sator Squares were discovered within the ruins of Pompeii. The fatal eruption of Vesuvius that buried the city occurred in AD 79, and it is very unlikely that there were any Christians there so soon after Christ’s death. But the city did have a large Jewish community, and many contemporary scholars see the Jewish Tau symbol in the TENET cross of the palindrome, as well as other Talmudic references across the square, as proof of its Jewish origins. Pompeii’s Jews faced pogroms throughout their history, and it makes sense that they might try to hide an expression of their faith within a Roman word puzzle.

Sator Squares spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and appear in the margins of Christian manuscripts, in important treatises on magic, and in a medical book as a cure for dog-bites. Over time, they gained popularity amongst the poor as a folk remedy, even amongst those who had no knowledge of Latin or were even illiterate. (Being ignorant of meaning might increase the potency of the magic by concealing the essential gibberish of the script). In 16th century Lyon, France, a person was reportedly cured of insanity after eating three crusts of bread with the Sator Square written on them.

As the square traveled across time and country, nowhere was it used more enthusiastically than in Germany and parts of the Low Countries, where the words were etched onto wooden plates and thrown into fires to extinguish them. There are early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stating that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.

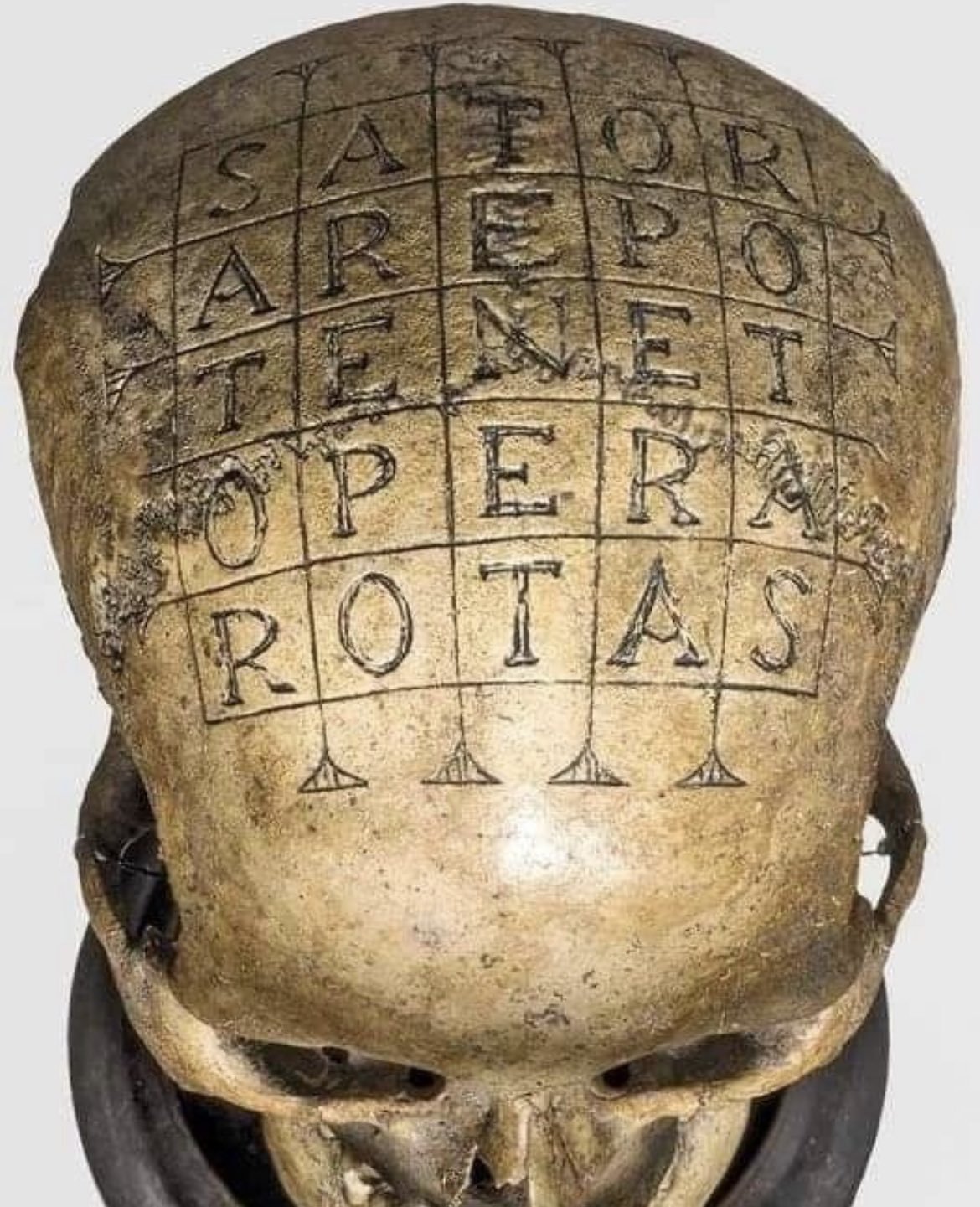

Oath Skull with Sator Square carved into bone.

From the same period comes a more sinister use of the square: The Oath Skull. Discovered in Münster in 2015 it is a human skull engraved with the Sator Square and radiocarbon dated between the 15th and 16th Centuries. It is believed to have been used by the Vedic Courts, a shadowy and ruthless court system that operated in Westphalia during that time. All proceedings of the courts were secret, even the names of judges were withheld, and death sentences were carried out by assassination or lynching. One of the few ways the accused could clear their names was by swearing an oath. Vedic courts used Oath Skulls as a means of underscoring the life-or-death nature of proceedings, and it is thought that the inclusion of the Sator Square on this skull added another level of mysticism - and the threat of eternal damnation - to the oath ritual.

When the poor of Europe headed for the New World, they took their beliefs with them. Sator Squares were used in the Americas until the late 19th century to treat snake bites, fight fires, and prevent miscarriages.

For 2000 years, interest in the Sator Squares has not waned, and a new generation has been exposed to them through the release of Christopher Nolan’s film TENET, named after the square. The film, about people who can move forwards and backwards in time, makes other references too: ‘Sator’ is the name of the arch villain played by Kenneth Branagh; ‘Arepo’ is the name of another character, a Spanish art forger whose paintings are kept in a vault protected by ‘Rotas Security’. In the film, ‘Tenet’ is the name of the intelligence agency that is fighting to keep the world from a temporal Armageddon.

Sator Squares have been described as history’s first meme. They have outlasted empires and nations, spreading across the western world and taking on newfound significance to each civilization that adopts them. Arepo should be proud of his work.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

Film

<div style="padding:41.67% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941483167?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The Naked Youth clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Iggy Pop Playlist

Iggy Confidential

Archival - May 8, 2015

Iggy Pop is an American singer, songwriter, musician, record producer, and actor. Since forming The Stooges in 1967, Iggy’s career has spanned decades and genres. Having paved the way for ‘70’s punk and ‘90’s grunge, he is often considered “The Godfather of Punk.”

The Four of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 25, 2024

The Four of Swords is air, at a point of stillness and equilibrium. This is a card of calm, and of temporary resolution to internal problems…

Name: Truce

Number: 4

Astrology: Jupiter in Libra

Qabalah: Chesed of Vau ו

Chris Gabriel May 25, 2024

The Four of Swords is air, at a point of stillness and equilibrium. This is a card of calm, and of temporary resolution to internal problems.

In Rider, we see a Gisant, or a tomb effigy. A young man depicted at rest, his image forever in prayer. His tomb bears a sword, and above him are the other three. In the top left corner, a stained glass window depicts a priest giving rites to a kneeling person.

In Thoth, we see four swords aimed at the center of a flower, forming a cross. We have the purple of Jupiter and the green of Libra. This is an expansive peace, a magnanimous truce. It calls to mind the Christmas Truce of World War 1 - out of jollity and a higher spirituality came temporary peace and mutual joy.

In Marseille, we have four arched swords and a central flower. Through Qabalah, we arrive at the Chesed of Vau, or the Mercy of Prince. The Mercy of the Prince is a Truce.

In this card we see beautiful but fragile rest, the violence of the suit brought to a brief standstill out of reverence to a higher force. This is a family dinner with differences put aside, a holiday party when bitter relatives agree to keep the peace for the sake of the season. There is something “higher” calling us to pause personal conflicts, whether it’s the religiosity and “goodwill” of a holiday, or the wellbeing of children and family. This is precisely the realm of Jupiter, that mercy and joy that beneficently orders conflict to cease for a moment.

This is in no way a solution, and may very well devolve into conflict if not carefully maintained, but it is a respite. We also see a serious divide in spiritual outlook between Rider and Thoth, when four, the stable number, is applied to swords. Is stability only truly attained in the grave? Or can a brief armistice give us the same thing?

Hamlet, yearning for peace, declares death the only end to heartache and the thousand natural shocks, but even then, the fear that this rest is illusion pervades his mind.

When dealt this card, we are being offered a temporary resolution, either to the internal conflicts within our restless minds, or the disagreements we have with those around us. Keep the truce, appreciate the respite, but prepare for things to break down, and quickly!

Questlove Playlist

WrdAlYnckvc

Archival - May Evening, 2024

Questlove has been the drummer and co-frontman for the original all-live, all-the-time Grammy Award-winning hip-hop group The Roots since 1987. Questlove is also a music history professor, a best-selling author and the Academy Award-winning director of the 2021 documentary Summer of Soul.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/942461068?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The Ranting of an Independent Filmmaker clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

The Power of Regret

Claudia Cockerell May 23, 2024

In the winter of 1981, a 22-year-old Texan called Bruce was on a train through Europe. A girl boarded at Paris and sat down next to him. They started chatting, and it felt like they’d known each other their whole lives. After a while they were holding hands. When it came to her stop they parted ways with a kiss. They never traded numbers, and Bruce didn’t even know her surname. “I never saw her again, and I’ve always wished I stepped off that train,” he wrote, 40 years on, in his submission to The World Regret Survey.

Melancholy, 1891. Edvard Munch.

Claudia Cockerell May 23, 2024

In the winter of 1981, a 22-year-old Texan called Bruce was on a train through Europe. A girl boarded at Paris and sat down next to him. They started chatting, and it felt like they’d known each other their whole lives. After a while they were holding hands. When it came to her stop they parted ways with a kiss. They never traded numbers, and Bruce didn’t even know her surname. “I never saw her again, and I’ve always wished I stepped off that train,” he wrote, 40 years on, in his submission to The World Regret Survey.

It’s a website you should visit if you ever need some perspective. Set up by author Daniel Pink, it asked thousands of people from hundreds of countries to anonymously share their biggest regrets in life. It’s strangely intimate, delving into the things people wish they’d done, or not done at all, and the answers run the gamut of the human condition.

For all the people who regret cheating on their partners, there are just as many who wish they’d never married them in the first place. One 66-year-old man in Florida regrets “being too promiscuous,” while a 17-year-old in Massachusetts says “I wish I asked out the girls I was interested in.” The stories range from quotidian (“When I was 13 I quit the saxophone because I thought it was too uncool to keep playing”) to tragic (“Not taking my grandmother candy on her deathbed. She specifically requested it”).

Sometimes we feel schadenfreude when reading about other people’s failings, but there’s something about regret that is pathos-filled and painfully relatable. Flicking through the answers, many of people’s biggest regrets are the things they didn’t do. We fantasise about what could have been if only we’d moved countries, switched jobs, taken more risks, or told someone we loved them.

“It just wasn’t meant to be. I still long for the sea - and to be near the waves”.

Pink wrote a book about his findings, called The Power of Regret. “We’re built to seek pleasure and to avoid pain - to prefer chocolate cupcakes to caterpillar smoothies and sex with our partner to an audit with the tax man”, he states. Why then, do we use our regrets to self-flagellate, more often wondering “if only…” rather than comforting ourselves with “at least”?

“One of the biggest regrets I have is not moving to California after graduating college. Instead I stayed in the midwest, married a girl, and ended up getting divorced because it just wasn't meant to be. I still long for the sea - and to be near the waves,” writes one man in Nebraska. This pining reflects the rose tinted lens through which we look at what could have been. California with its rolling waves and sandy beaches is synonymous with a life of freedom, love, and joy.

Studland Beach, 1912. Vanessa Bell.

Instead of categorising regrets by whether they are work, money, or romance related, Pink has created a new system, arguing that regrets fall into four core categories: foundation, moral, boldness and connection regrets. Within these groups, there are regrets of the things we did do (often moral), and things we didn’t do (often connection and boldness regrets). The things we didn’t do are frequently more painful because, as Pink says, ‘inactions, by laying eggs under our skin, incubate endless speculation’. So you’re better off setting up that business, or asking that girl out, or stepping off the train, because of the inherently limited nature of contemplating action versus inaction.

The actions which we do end up regretting are often moral failings that fall under the umbrella of a ten commandments breach. As well as adultery, larceny and the like, there’s poignant memories of childhood cruelty. A 56-year-old woman in Kansas still beats herself up about something she did 45 years earlier: “Throwing rocks at my former best friend in 6th grade as she walked home from school. I was walking behind her with my “new” friends. Terrible.”

But regrets can have a galvanising effect, if we choose to let them. Instead of wallowing in the sadness of wishing we could rewind time, or take back something horrible we said or did, we can use that angsty feeling as an impetus for change. “When regret smothers, it can weigh us down. But when it pokes, it can lift us up,” says Pink. There’s an old proverb which has probably been cross-stitched earnestly onto many a cushion, but I still like it as a mantra for overcoming pangs of regret: “The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second-best time is today.”

Claudia Cockerell is a journalist and classicist.

Tom O’Neill

2hr 45m

5.22.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with ‘CHAOS’ author Tom O’Neill about the mystery of Charles Manson’s magnetic persona.

<iframe width="100%" height="265" src="https://clyp.it/fwiyxjwa/widget?token=3ce0e3b91ac2095d250fc664df72fa2f" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Grasping at Gesture

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

Hand Catching Lead, 1968. Richard Serra.

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

In the first of these texts on gesture, I traced an unreliable and partial history of hand gestures – from roman orators and Martine Syms, to teens on TikTok and TikToks of tech bros using Apple Vision Pro – and how, somewhere along the way we lost our gestures, or lost control of them; gesticulating wildly in the open air.

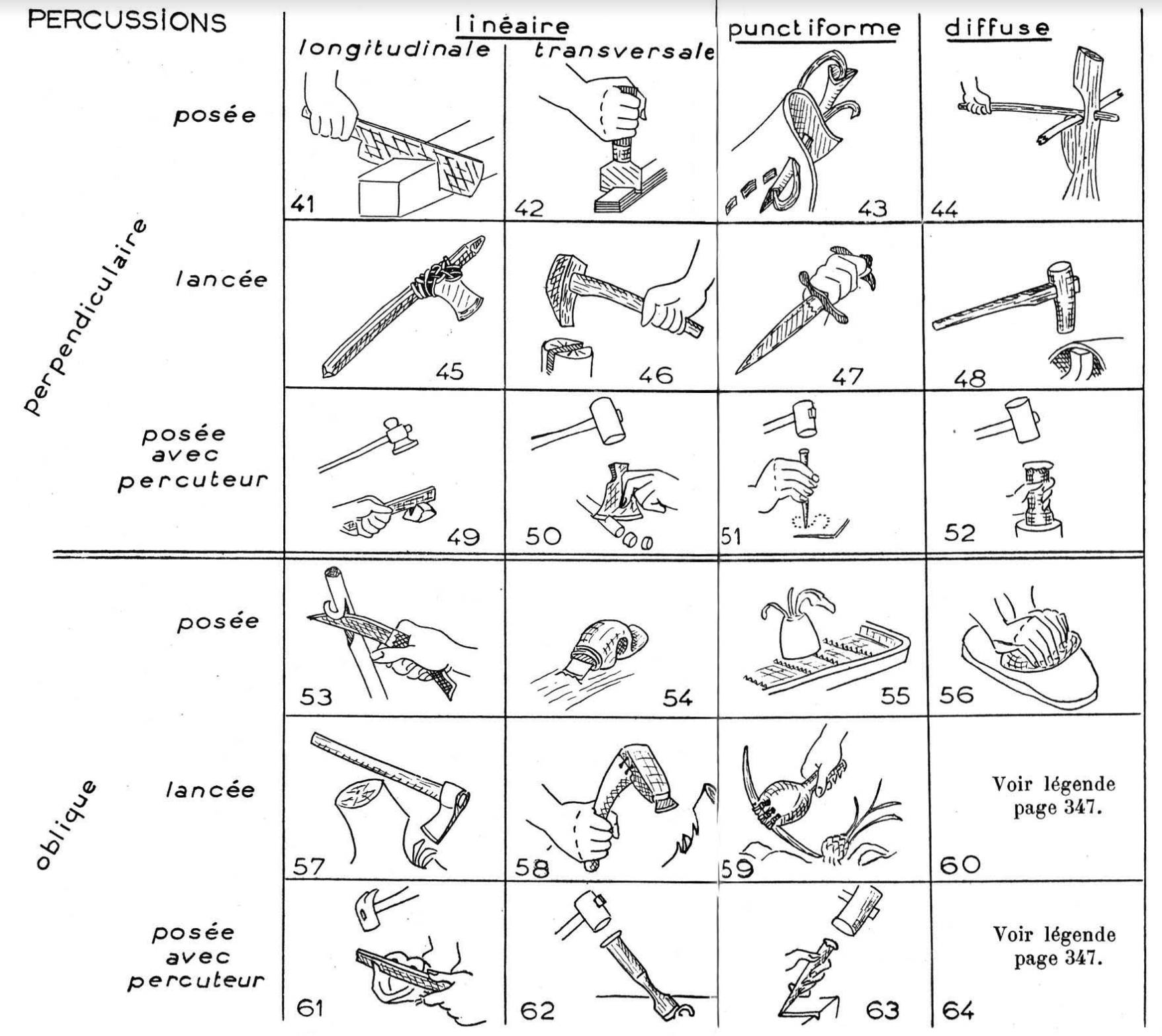

Man and Matter, 1943. Leroi-Gourhan.

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

‘The essential traits of human technical gesticulation are undoubtedly connected with grasping’¹ said Andre Leroi-Gourhan in his 1965 book, Gesture and Speech. A pioneering anthropologist, Leroi-Gourhan traced evolving relationships between hands, tools, gestures, languages, and thoughts, and developed a corresponding science for such. He is associated with Structuralist school, which means that he sought out the underlying processes (or structures) that make systems meaningful. Leroi-Gourhan’s Gesture and Speech does many things: It traces a bio-cultural evolution of postures, hands, brains, tools, art and language, up to the present day; conducts cross-cultural analysis of the rhythms and organization of human society, value systems, social behavior and techno-economic apparatus; and, amidst nascent developments in robotics and early experiments in automation, speculates on the future of our species.

“Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot.”

Alcuni Monumenti del Museo Carrafa, 1778.

The book begins with a history of the human brain and hand, with Leroi-Gourhan explaining: ‘it seemed to me that the first thing to do was to measure the results of what can be done with the hand to see what [our]brains can think.’² In pursuing both brain and hand he opposed the prevailing approach in evolution studies to focus only on the ‘cerebral’. Leroi-Gourhan was interested in how thought is embodied, how it springs from material conditions.

So, what can be done with the hand? Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot; they could grip and grasp and gesture. Now grasping is not specific to humans – qualitatively, the hand that grasps remains a relatively rudimentary device that's accompanied us across many evolutionary stages – and there are a variety of types and properties of grasps. Studying the transition from instinctive to cultural uses of hands, Leroi-Gourhan observed the functional shift from the mouth to the hand, from the hand to the grasped tool, and finally the hand that operates the machine. When it comes to grasping, ‘the actions of the teeth shift to the hand, which handles the portable tool; then the tool shifts still further away, and a part of the gesture is transferred from the arm to the hand-operated machine’. This he describes as a gradual exteriorization, or ‘secretion’ of the hand-and-brain into the tool.

But gesture still somewhat eludes us, its location ambiguous. Gesture is not in and of the hand, nor in and of the tool, rather gesture is the meeting of brain, hand and tool, the driving force and thought that sets the tool to action. To bring these gestures to light, Leroi-Gourhan developed the methodology for which he is best known: the Chaîne Opératoire.

The Chaîne Opératoire, or operational chain, is a method that makes processes visible by documenting the sequence of techniques that bring things into being – be they tangible artifacts, ephemeral performances, or even the acquisition of intangible status. Leroi-Gourhan described a technique as ‘made of both gesture and tool, organized in a chain by a true syntax’. The use of ‘syntax’ here (Structuralists had a thing for linguistics) establishes a relationship between the processes and the performance of language where there is room for both shared meaning and individual flourishes. Here, gesture, like the arrangement of words in a sentence, is relational, acquiring its shape and meaning through the interaction of mind, body, tool, material and social worlds in which it participates.

This whole time thinking about grasping hands I’ve had a film in mind: Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead, in which morsels of lead fall from above, are caught, and then released by the artist's hand. Far from mechanically consistent, sometimes Serra grasps the object, sometimes he grasps at it, narrowing missing and smacking fingers to palm. From 1968 into the early 70s Serra made a series of other hand films whose subject matter are just as the titles suggest: in Hand Catching Lead a hand, of course, catches lead; in Hands Scraping (1968) two pairs of hands gather up lead shavings which have accumulated on the floor/filled the frame; in Hands Tied two tied-uphands untie themselves.

“The creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool.. can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties.”

Hands Scraping, 1968. Richard Serra.

Curator Søren Grammel said Serra’s hand works ‘demonstrate a particular action that can be applied to a material’. I suppose that’s what the Chaîne Opératoire gets at too, as well as demonstrating how the material acts on us; in Hand Catching Lead, the lead rubs off onto Serra’s blackened hands. And just as the Chaîne Opératoire observes the network of gestures that fulfill an operation, the duration of Serra’s films cosplay pragmatism, lasting as long as it takes to complete the task (however arbitrary): How many pieces of lead can you catch or not catch until you are exhausted/cramp-up/are no longer interested? How long does it take to sweep up lead shavings or untie a knot?

Serra’s Hand Catching Lead was prompted in part by being asked to document the making of House of Cards (a sculpture where four large lead sheets are propped against one another to form the sides of a cube). But a film following the making process would, he felt, be too literal and merely illustrative. Instead, Hand Catching Lead is a ‘filmic analogy’ of the creative process. Serra knew that the creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool like the Chaîne Opératoire can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties. It seems we have come up against the limits of this approach, and of Structuralism's commitment to linguistics. Returning to Agamben, who we met in the first text: ‘being-in-language is not something that could be said in sentences, the gesture is essentially always a gesture of not being able to figure something out in language; it is always a gag in the proper meaning of the term…’³ Perhaps then Serra’s grasps are gags, grasping at lead, at air and at the irrepresentable nature of being-in-gesture.

¹ Andre Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1993) [1965]), 238

² ibid.,146

³ Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000) 59

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer, researcher and editor. She is the co-founding editor of motor dance journal.

Film

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941497753?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The biggest difference between bad art and great art"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

Lobby Loyde - Play with George Guitar (Out of Print)

Matt Sweeney May 20, 2024

Australian rock legend Lobby Loyd is sorta like Lemmy, Neil Young, and Malcolm Young and this album is him on a ton of acid. His band Coloured Balls’ essential 1973 album is “Ball Power.” A mint copy of the vinyl cost like $500 in the ‘90’s.

Matt Sweeney May 20, 2024

Australian rock legend Lobby Loyd is sorta like Lemmy, Neil Young, and Malcolm Young and this album is him on a ton of acid. His band Coloured Balls’ essential 1973 album is “Ball Power.” A mint copy of the vinyl cost like $500 in the ‘90’s.

Matt Sweeney is a record producer and the host of the popular music series “Guitar Moves”. He is a member of The Hard Quartet (debut album out Fall of 2024). Rick reached out to Matt Sweeney in 2005 after hearing his “Superwolf” album, and invited him to play on albums by Johnny Cash, Neil Diamond, Adele and many others. Follow Matt Sweeney via Instagram.

The Six of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 11, 2024

The World card is a cosmogram, meaning it depicts the whole of the cosmos. We find a naked woman floating within a ring, her legs crossed and something flowing about her. She is Maya, the embodied force of creation and illusion. Her dancing and spinning manifests the material world. The Four Cherubs frame the corners as symbols of the states of matter…

Name: Science

Number: Six

Astrology: Mercury in Aquarius

Qabalah: Tiphereth of Vau ו

Chris Gabriel May 18, 2024

The Six of Swords is a rare positive card in the suit. Here the winds of thought are well directed, and applied with intention and effect. This is a card of knowledge, and the acquisition thereof.

In Rider, we find a ferryman guiding a skiff with a huddled woman and child. The sky is grey, and the waters before them are still. This is a card of safety and retreat, and especially in the context of the grim visages that fill the suit of Swords, this is a positive card.

In Thoth, we find six swords aimed directly at a rose within a cross. About the swords are a geometric figure, a squared circle that has formed out of the chaotic shapes fluttering about the borders. We have the purplish greys of Aquarius and the gold of Mercury. This is the cross of the Rosicrucians. This card is the mind understanding the machinations of the universe.

In Marseille, we see six arched swords and a central flower. Qabalah tells us the six of swords is Tiphereth of Vau, or the Beauty of the Prince.

The Beauty of the Prince is his science, the way he learns, understands, and applies that knowledge.

As I’ve expressed before, the suit of swords evokes Hamlet, and this is the image of Hamlet the Scientist, Hamlet the Psychologist. Seen as such, we can interpret a great deal of Hamlet’s actions as experiments; consider the Mousetrap. Hamlet hypothesizes that Claudius kills his father, he puts on a play he calls “The Mousetrap” to prove this. The play’s the experiment!

As for Rider, we can think again to Hamlet, to his general ability to survive the treacherous court, feigning madness, going unpunished for murder, making off with pirates, evading execution, etc. His death is in many ways a suicide (which we’ll see later in the suit). But clearly, his understanding of his situation allows him to survive and escape death.

Thoth shows this science applied to the rosy cross, which is the symbol on the back of all Thoth cards. The rosy cross is a cosmogram, whose arms are the four elements, and whose petals are the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. In essence, an esoteric depiction of the universe, making this card a symbol of esoteric study itself.

When dealt this card we are being given an opportunity to develop our understanding of the things around us, to create a science of ourselves, and to then apply that knowledge in our lives.

Hannah Peel Playlist

Metatron’s Cube 2

Archival - April 23, 2024

Mercury Prize, Ivor Novello and Emmy-nominated, RTS and Music Producers Guild winning composer, with a flow of solo albums and collaborative releases, Hannah Peel joins the dots between science, nature and the creative arts, through her explorative approach to electronic, classical and traditional music.

Film

<div style="padding:80% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941483130?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="C.C. and Company clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

More Than Meets the Eye - 1. Light, Science, Life.

Matthew Maruca May 16, 2024

In 1917, halfway through a career of developing theories and equations that changed our understanding of the world, Albert Einstein famously said “for the rest of my life, I will reflect on what light is.”

"Spectra of various light sources, solar, stellar, metallic, gaseous, electric" - Les Phénomènes de la Physique (1868). René Henri Digeon

Matthew Maruca May 16, 2024

In 1917, halfway through a career of developing theories and equations that changed our understanding of the world, Albert Einstein famously said “for the rest of my life, I will reflect on what light is.”

Substance or energy? Particle or wave? Light is a mysterious force, which links our internal experience to the external world. Or, does it create our internal experience, from the external world?

In our basic experience, light allows us to see. From the youngest age, we come to know that the “light switch” illuminates a dark room, allowing us to experience the room, without bumping into objects, tripping over things, and hurting ourselves. The world is already there, and we are a part of it, but without visible light, our conscious experience of the world is significantly limited. And it is vastly expanded by the presence of light.

We must then ask if this biological, biochemical, photochemical phenomenon that we call “light” allows our brain to consciously experience the material world around us, or if it is light that is actually creating our experience of the world. When the light is gone, we don’t have the same experience of the world; and when it’s present, we do. So it must be - in some way - creating our experience. What then, are we actually experiencing? To answer this, we must understand what exactly light is.

Light. And Science.

From the Bible to the Big Bang, several of the most influential stories of creation start with vibration or energy, which is not light. In many religions, this is the “Word”, the Cosmic Sound “Aum”, the voice of God the Creator; in science it is simply considered vibrational energy. And then, after the vibration, there is light.

Le Monde Physique (1882). Alexandre-Blaise Desgoffe.

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night.

And the evening and the morning were the first day.”

(Genesis 1:1-5, KJV)

This Biblical account of creation, where the voice of God is speech, is sound and vibrations, and comes before light is reflected in the scientific accounts of the origin of the universe. Light did not appear until some 380,000 years after the initial “Big Bang”, and while the first photons were created shortly after the Big Bang, they were immediately re-absorbed by different particles and so the universe was “opaque” during this time. Only after the universe cooled to a temperature of around 3000K, could protons and electrons begin to combine to form hydrogen, allowing perceptible light to move freely without being immediately absorbed. And then, there was light, in the form that we see.

From the perspective of science, light is a form of energy, the result of one of the four fundamental forces (a.k.a “interactions”), which govern everything in the known universe. Light is the term we use to describe the visible range of the broader spectrum of “electromagnetic radiation”, which comprises both the light we can see, and forms of radiation we cannot see, such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared light, ultraviolet light, X-rays, gamma rays, and so on. The photons responsible for light are one of the fundamental particles created by the initial Big Bang.

It wasn’t until 1801, when a British physicist named Thomas Young performed an experiment called “the double-slit experiment”, that we began to grasp what light really is, a question we are still grappling with. Young projected light through two parallel slits in one surface, with another surface behind it. When the light hit the back surface, he expected to see a pattern showing the slits through which the light had passed. Instead, what he saw was several, spaced-out lines of light, indicating that the light traveled more like waves, canceling itself out in certain places, while becoming stronger in others. This opened up the debate as to whether light is really a particle or a wave.

It is understood that electromagnetic radiation, a spectrum that includes visible light as well as forms of radiation we cannot see, is created and emitted in the process of nuclear fusion. This began first in the origin of our universe and now occurs in stars such as our sun, when hydrogen atoms are pushed together under tremendous pressure to form larger helium atoms. Some of the matter which makes up these atoms is converted, but not created, into energy and radiated out as light.

Another common way that light is emitted is from electromagnetic interactions between energy and atoms. In a fluorescent lamp, electricity is injected into a tube filled with mercury vapor. The mercury atoms absorb this electricity but then become unstable and quickly re-emit it as mainly invisible light. This light is then absorbed by the phosphor coating on the inside of the tube, which converts it in a range that is visible to the human eye. and is then re-emitted. This process of conversion of photons with higher quantum energies into lower ones is called “fluorescence”. The energy began in the form of electricity on a copper wire being injected into the light tube (before this, it may have been energy trapped in coal, oil, or moving in the form of wind, solar, or geothermal energy, as well).

That’s just a brief summary of the science of light, what it is, and where it comes from. There is still so much we don’t understand about the nature of light but, we know, at least, that light is absolutely fundamental to our existence.

Light. And Life.

What would happen if the sun didn’t come up tomorrow or the next day and ever after? Very quickly, within days or weeks, Earth would begin to freeze. The energy of the sun provides the warmth which is a prerequisite for life on Earth but the sun offers more than warmth. The light that comes to earth powers photosynthesis—the production of all plant matter, powered by sunlight splitting water, allowing it to bind with carbon dioxide and make sugar, the basic building block of all plant matter. Without sunlight, no crops could grow and just as importantly, all of the ocean’s phytoplankton, and land’s jungles and rainforests would die, robbing the atmosphere of its oxygen. Without oxygen, complex life, which is based on energy-producing mitochondria that use oxygen to generate energy, would fail. Life on Earth is the result of the conditions provided by sunlight. Life is not just built by sunlight, but it is sustained by its power. Light is essential for keeping the “system of life” in motion.

Cloud Shadow With Red Diffusion Light During the Disturbance Period (1884). Eduard Pechuël-Loesche.

Earlier on, we established that light is a fundamental part of our conscious experience of the world. And while there are still questions as to the nature of lightself, we know even less about the nature of consciousness.The two are closely linked, and great spiritual teachers throughout history have described our consciousness as a form of energy which is either directly connected or very closely related to light.

Traditional Chinese Medicine speaks of “Qi”, the life force energy which courses through our meridians, giving us life, and, when out of balance, can lead to disease. People have practiced exercises like “tai chi” and “qi gong” for millennia to care for this energy. A very similar perspective exists in the traditional religions of India as the concept of “prana”, and practices like meditation and “pranayama” breathwork sustain, nourish, and enhance this vital “life force” energy. In the West, scientists have found tremendous benefits from meditation (a PubMed search on the term yields over 10,000 results), yet they lack clear, definite mechanisms to explain these effects. Many doctors and leading healthcare institutions are beginning to prescribe alternative treatments like acupuncture and meditation to support patients’ health and well-being. This “life force” energy may not exactly be light; it may be more like electricity. But in the same way that solar power can be converted into electricity, and electricity can be converted back into light in a lamp, these different forms of energy within us are related, even if we don’t fully understand them.

It’s clear that the existence of life on Earth is inextricably linked to the conditions given by sunlight. We could even say that life on Earth is the result of the conditions provided by sunlight. Life, as we know it, is a product of the interaction between sunlight and the elements on the Earth’s surface.

Matt Maruca is an entrepreneur and journalist interested in health, science, and scientific techniques for better living, with a focus on the power of light. He is the Founder & CEO of Ra Optics, a company that makes premium light therapy products to support optimal health in the modern age. In his free time, he enjoys meditation, surfing, reading, and travel.

Serj Tankian

1hr 38m

5.15.24

In this clip, Rick speaks with System of a Down front man Serj Tankian about the band’s unique chemistry.

<iframe width="100%" height="75" src="https://clyp.it/fdp12viw/widget?token=8aee3c9b5ad57fd6c9ca3b5d7f90c6dc" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Film

<div style="padding:75% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/941494892?badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="Tomorrow and tomorrow clip"></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

What Do The Fungi Want?

Tuukka Toivonen May 14, 2024

Creative ideas grow, mutate and flourish through conversations between people. However casual or mundane, these exchanges have the potential to reveal novel possibilities, or dramatically shift the course of a fledgling idea. Direct interactions are a tremendous source of motivation for creators. The best ones possess a much-overlooked generative power…

Fly Agaric Watercolor, 1892. Leigh Woods.

Tuukka Toivonen May 14, 2024

Creative ideas grow, mutate and flourish through conversations between people. However casual or mundane, these exchanges have the potential to reveal novel possibilities, or dramatically shift the course of a fledgling idea. Direct interactions are a tremendous source of motivation for creators. The best ones possess a much-overlooked generative power.

This was the basic premise of the research I was involved in as a sociologist until, a few years ago, I stumbled across interspecies creativity. I had become intrigued by how certain colleagues – designers and artists, especially – spoke passionately about how they sought to ‘create with and for nature’ or even ‘as nature’ when making new textiles, garments or artworks. They felt strongly that it was time to start treating living organisms and ecosystems as genuine collaborators and co-creators in their process.

Atlas des Champignons (1827). M. E. Descourtilz,

Spellbound by the prospect of novel ideas and designs emerging from humans collaborating with algae, mycelium and slime mould, I started to wonder about the practical and philosophical implications of such phenomena. For me, the question was not only about understanding the material qualities of particular organisms, it was about how humans might transform themselves into genuine co-creators in relation to nonhumans.

The notion of ‘creating with nature’ can be confounding – it was for me. Beyond the crude physical barriers that keep nonhuman and human lives separate, prevailing worldviews order us to place animals, plants, insects and fungi in a fundamentally different category from humans who – whilst animal – have developed complex cultures, technologies and societies, making us ‘unstoppable’, even ‘superior’. As a result of this human-centric conditioning, we are hopelessly unaccustomed to viewing nonhuman life as intelligent. Experts of human organizational life argue that perspective-taking – in essence, making an effort to imagine the point of view of another person or persons – is key to successful communication and management, and even constitutive of our ability to be ‘fully human’. There is no such chorus calling us to seriously listen or sensitize ourselves to the perspectives of nonhumans.

To explore species-crossing creativity further (in the hope of transcending or ameliorating the non/human barrier), we decided to hold in-depth conversations with a dozen biodesigners and bioartists, as well as a few progressive entrepreneurs. The creators were growing sneakers with bacteria that produce nanocellulose, working with microalgae to purify water contaminated by fashion dyes, and sewing fabrics from wild plants, among other fascinating experimental practices.

One outspoken participant explained that, in the early stages of the creative process, he always sought to engage as directly and viscerally with a living organism as possible, relentlessly looking for promising ways to collaborate. Having developed a particular interest in working with mycelium at a mass scale, he soon became curious not only about the material co-design possibilities of this organism, but also its behaviours and its needs. A simple yet pivotal question emerged: ‘What does the fungi want?’ His next steps as a designer and entrepreneur would be derived from that simple query.

Nearly all the creators we spoke to expressed an active curiosity about the needs of the organisms they were engaging with. Working with diverse plant species as well as digital technology, one participant recounted how she explored the way plants sense the world, their sensitivity to light and sound, and their ways of communicating with other organisms. Another spoke of the profundity of learning to collaborate with organisms whose existence on earth predated that of humans by millions of years.

“By subtly observing and interacting with diverse organisms, creators can establish equality of existence with all forms of life.”

The Intruder (c.1860). John Anster Fitzgerald.

What does it mean, really, to think in terms of what a nonhuman organism ‘needs’, ‘wants’ or ‘likes’? Do such queries belie a deeper significance, an alternative way to view human-nature relations?

The visionary work of the British anthropologist Tim Ingold may help us understand why inquiring into the ‘needs’ and ‘wants’ of organisms is not just naïve anthropomorphism. In his discussion of how the people of the North American Cree Nation situate themselves in relation to their surroundings, Ingold uncovered a relevant mode of being that transcends central dichotomies that govern our (Western) thinking with regards to nonhuman life:

“From the Cree perspective, personhood is not the manifest form of humanity; rather the human is one of many outward forms of personhood. And so when Cree hunters claim that a goose is in some sense like a man, far from drawing a figurative parallel across two fundamentally separate domains, they are rather pointing to the real unity that underwrites their differentiation” (from Tim Ingold’s The Perception of the Environment, 2001).

Ingold explains that, unlike Western approaches that begin from an assumption of fundamental difference between humans and animals (leading us to search for possible analogies and anthropomorphisms, describing many animal behaviours and features in terms of their resemblance to humans), indigenous communities have typically done the opposite: starting from an assumption of similarity. For this reason, in such communities “it is not ‘anthropomorphic’ […], to compare the animal to the human, any more than it is ‘naturalistic’ to compare the human to the animal, since in both cases the comparison points to a level on which human and animal share a common existential status, namely as living beings and persons”. It is owing to this holistic worldview that the Cree assign personhood and utmost value to animals, forests, rivers and other parts of the living world, the all-important commonality with humans being their aliveness, animateness, or their potential to become an animate being.

And so we find that hidden inside our question – what does the organism need? – lies an entirely different, non-dichotomous approach to being. Indeed, by subtly observing and interacting with diverse organisms, creators can establish equality of existence with all forms of life.

It is not that we should believe that fungi or microalgae – or larger animate entities such as rivers or lakes – possess a will or preferences exactly like those of humans. Rather, it is that through these acts of curiosity and questioning, we place ourselves on a single life plane, opening up space for genuine interaction. . From this vantage point, asking ‘what does the fungi want?’, is a radical act in the context of a technological society, contesting the deep dichotomies of ‘modern’ life. Importantly, adopting this orientation rejects the totalizing tendency to position science as the only legitimate route to gaining knowledge, by restoring our ability to enter into direct, unmediated and authentic relations with other forms of life. This way of questioning can take us a surprisingly long way towards transforming ourselves into genuine collaborators and co-creators for other species.

So, what did the fungi want? In the case of the particular designer mentioned earlier, one Bob Hendrix, the answer turned out to be that they wanted to digest and recycle organic matter, specifically, humans. That insight led the designer down a path of developing mycelium-based coffins, with a view to helping humans to become useful, welcome participants in more-than-human ecosystems at the end of their lives, gifting life-giving soil with precious nutrients and energy.

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.