The Poetic Diary of Ramuntcho Matta (Excerpt II)

Ramuntcho Matta May 30, 2024

How to become a better me?

But first, what do you call me? How do you call me? There are no special lines, no direct lines. There are only paths mades of confusions, pains and distraught. Paths mades of encounters, dances and sleeps…

Ramuntcho Matta May 30, 2024

I.

How to become a better me?

But first, what do you call me? How do you call me? There are no special lines, no direct lines. There are only paths mades of confusions, pains and distraught. Paths mades of encounters, dances and sleeps.

In the South of France there is a land that does not want to be a country. The people there do not want borders. Are there borders anyway?

I am here with a Basque cake, I sit on a bench and they come, all dressed in white, in red and strange hats.

All dressed in white?

It reminds me a song,

All dressed in black?

They come and they dance, each village has their own version. Does your body remember the dance? It does but you can’t recall.

Basque Identity is a moving cross, a representation of the four elements. But we know we have five elements. We have five fingers because we are five elements.

Every day, I will practice my five elements. Water > earth > wood > metal > fire. 3 times, sometimes more. This is the first exercise. At the beginning you will feel very little but after a few weeks you will start to enter in a new dimension and after 4 years you will be water, earth, wood, metal and fire.

You already have this in you but you are not trained to feed yourselves with those sensations.

II.

As a child becomes a flower when they see a flower…

you have to be water that becomes earth,

earth that becomes wood,

wood that becomes metal,

metal that becomes fire,

fire that becomes water,

water that becomes…

That becoming is the essence of being.

Being an animal,

being a human,

being a chair,

a nice meal,

an old stone.

The other day I was invited to present my drawings. In my life of brushstrokes, sometimes words show up. Where they come from is not relevant, where they drive me… that’s the point.

I started to play with my guitar and a dog showed up, so i wanted him to sing, and here we are, a dog’s song… the blues of a dog.

What is “me“ for a dog ? What is his “self“, his “I“? What is the balance between “I“ and “me“ that could make a better “self“?

A dog does not care about this because he does not care about knowing more: instead, he feels more. Much more.

I remember the song.

All dressed in black,

walking the dog,

being a dog…

III.

I can show you how to enter into that dimension. There are exercises and practices but if you are not ready it will be useless. Brion Gysin and Bill Burroughs wanted to create a school but very soon they felt that this kind of knowledge is not for everybody. So transmission should be more maieutics.

Back to the drawing: you see the triangle… “me“ is the body. “I“ the mind. How much of your body is your self? How much of your mind?

Do you mind?

Do you body?

“I don’t mind“,

What a curious sentence.

The rhythm of the phrases is at least as important as the meaning of the words. This is what Bill used to say.

Now you can feel more,

Feeling is not a knowledge

It is a dimension of being.

Ramuntcho Matta is a producer, sound designer and visual artist.

Sator Squares (Artefact III)

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies…

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 3

Location: Across Europe and the Americas.

Age: 2000 years

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies.

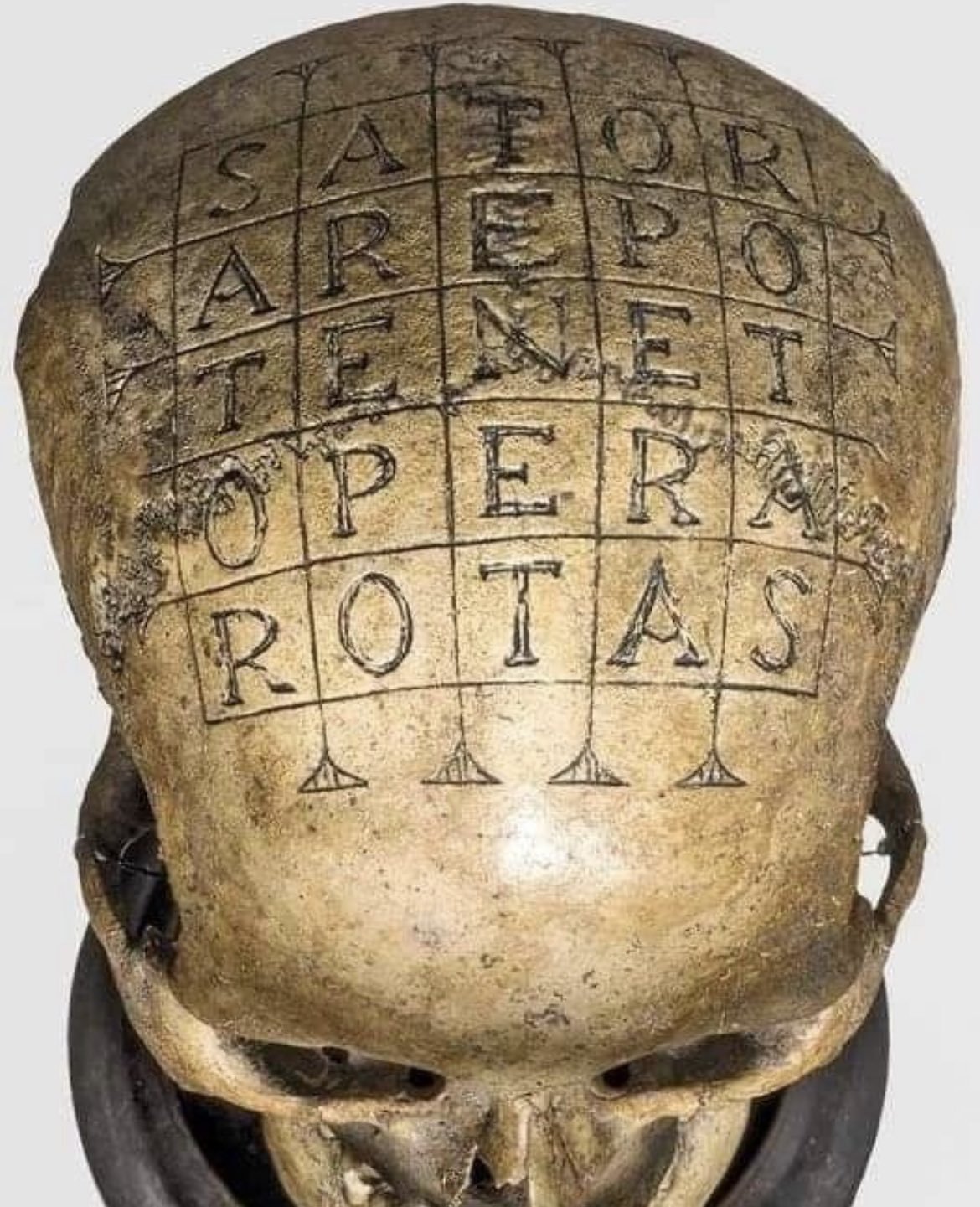

Sator Square in the village of Oppède le Vieux.

The “it” in question is the Sator Square. A Latin, five-line palindrome, it can be read from left or right, upwards or downwards. The earliest ones occur at Roman sites throughout the empire and by the Middle Ages, they had spread across northern Europe and were used as magical symbols to cure, prevent, and sometimes play a role in all sorts of wickedness. The one pictured here is set in the doorway of a medieval house in the semi-ruined village of Oppède le Vieux, Provence, France, carved to ward off evil spirits.

There are several different translations of the Latin, depending on how the square is read. Here is a simple version to get us started:

AREPO is taken to be a proper name, so, AREPO, SATOR (the gardener/ sower), TENET (holds), OPERA (works), ROTAS (the wheels/plow), which could come out something like ‘Arepo the gardener holds and works the wheels/plow’. Other similar translations include ‘The farmer Arepo works his wheels’ or ‘The sower Arepo guides the plow with care’.

Some academics insist that the square is read in a boustrophedon style, meaning ‘as the ox plows’, which is to say reading one line forwards and the next line backwards, as a farmer would work a field. Such a method would not only emphasize the agricultural nature of the square but also allow a more lyrical reading and could be very loosely translated thus: “as ye sow, so shall ye reap.”

“Early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stated that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.”

Sator Square with A O in chi format.

There are multiple translations and theories surrounding Sator Squares. They became the focus for intense academic debate about 150 years ago. Most of the early studies assumed that they were Christian in origin. The earliest known examples at that time appeared on 6th and 7th century Christian manuscripts and focussed on the Paternoster anagram contained within: by rearranging the letters, the Sator Square spells out Paternoster or ‘our father’, with the leftover A and O symbolizing the Alpha and the Omega.

However, in the 1920s and 30s, two Sator Squares were discovered within the ruins of Pompeii. The fatal eruption of Vesuvius that buried the city occurred in AD 79, and it is very unlikely that there were any Christians there so soon after Christ’s death. But the city did have a large Jewish community, and many contemporary scholars see the Jewish Tau symbol in the TENET cross of the palindrome, as well as other Talmudic references across the square, as proof of its Jewish origins. Pompeii’s Jews faced pogroms throughout their history, and it makes sense that they might try to hide an expression of their faith within a Roman word puzzle.

Sator Squares spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and appear in the margins of Christian manuscripts, in important treatises on magic, and in a medical book as a cure for dog-bites. Over time, they gained popularity amongst the poor as a folk remedy, even amongst those who had no knowledge of Latin or were even illiterate. (Being ignorant of meaning might increase the potency of the magic by concealing the essential gibberish of the script). In 16th century Lyon, France, a person was reportedly cured of insanity after eating three crusts of bread with the Sator Square written on them.

As the square traveled across time and country, nowhere was it used more enthusiastically than in Germany and parts of the Low Countries, where the words were etched onto wooden plates and thrown into fires to extinguish them. There are early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stating that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.

Oath Skull with Sator Square carved into bone.

From the same period comes a more sinister use of the square: The Oath Skull. Discovered in Münster in 2015 it is a human skull engraved with the Sator Square and radiocarbon dated between the 15th and 16th Centuries. It is believed to have been used by the Vedic Courts, a shadowy and ruthless court system that operated in Westphalia during that time. All proceedings of the courts were secret, even the names of judges were withheld, and death sentences were carried out by assassination or lynching. One of the few ways the accused could clear their names was by swearing an oath. Vedic courts used Oath Skulls as a means of underscoring the life-or-death nature of proceedings, and it is thought that the inclusion of the Sator Square on this skull added another level of mysticism - and the threat of eternal damnation - to the oath ritual.

When the poor of Europe headed for the New World, they took their beliefs with them. Sator Squares were used in the Americas until the late 19th century to treat snake bites, fight fires, and prevent miscarriages.

For 2000 years, interest in the Sator Squares has not waned, and a new generation has been exposed to them through the release of Christopher Nolan’s film TENET, named after the square. The film, about people who can move forwards and backwards in time, makes other references too: ‘Sator’ is the name of the arch villain played by Kenneth Branagh; ‘Arepo’ is the name of another character, a Spanish art forger whose paintings are kept in a vault protected by ‘Rotas Security’. In the film, ‘Tenet’ is the name of the intelligence agency that is fighting to keep the world from a temporal Armageddon.

Sator Squares have been described as history’s first meme. They have outlasted empires and nations, spreading across the western world and taking on newfound significance to each civilization that adopts them. Arepo should be proud of his work.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

The Four of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 25, 2024

The Four of Swords is air, at a point of stillness and equilibrium. This is a card of calm, and of temporary resolution to internal problems…

Name: Truce

Number: 4

Astrology: Jupiter in Libra

Qabalah: Chesed of Vau ו

Chris Gabriel May 25, 2024

The Four of Swords is air, at a point of stillness and equilibrium. This is a card of calm, and of temporary resolution to internal problems.

In Rider, we see a Gisant, or a tomb effigy. A young man depicted at rest, his image forever in prayer. His tomb bears a sword, and above him are the other three. In the top left corner, a stained glass window depicts a priest giving rites to a kneeling person.

In Thoth, we see four swords aimed at the center of a flower, forming a cross. We have the purple of Jupiter and the green of Libra. This is an expansive peace, a magnanimous truce. It calls to mind the Christmas Truce of World War 1 - out of jollity and a higher spirituality came temporary peace and mutual joy.

In Marseille, we have four arched swords and a central flower. Through Qabalah, we arrive at the Chesed of Vau, or the Mercy of Prince. The Mercy of the Prince is a Truce.

In this card we see beautiful but fragile rest, the violence of the suit brought to a brief standstill out of reverence to a higher force. This is a family dinner with differences put aside, a holiday party when bitter relatives agree to keep the peace for the sake of the season. There is something “higher” calling us to pause personal conflicts, whether it’s the religiosity and “goodwill” of a holiday, or the wellbeing of children and family. This is precisely the realm of Jupiter, that mercy and joy that beneficently orders conflict to cease for a moment.

This is in no way a solution, and may very well devolve into conflict if not carefully maintained, but it is a respite. We also see a serious divide in spiritual outlook between Rider and Thoth, when four, the stable number, is applied to swords. Is stability only truly attained in the grave? Or can a brief armistice give us the same thing?

Hamlet, yearning for peace, declares death the only end to heartache and the thousand natural shocks, but even then, the fear that this rest is illusion pervades his mind.

When dealt this card, we are being offered a temporary resolution, either to the internal conflicts within our restless minds, or the disagreements we have with those around us. Keep the truce, appreciate the respite, but prepare for things to break down, and quickly!

The Power of Regret

Claudia Cockerell May 23, 2024

In the winter of 1981, a 22-year-old Texan called Bruce was on a train through Europe. A girl boarded at Paris and sat down next to him. They started chatting, and it felt like they’d known each other their whole lives. After a while they were holding hands. When it came to her stop they parted ways with a kiss. They never traded numbers, and Bruce didn’t even know her surname. “I never saw her again, and I’ve always wished I stepped off that train,” he wrote, 40 years on, in his submission to The World Regret Survey.

Melancholy, 1891. Edvard Munch.

Claudia Cockerell May 23, 2024

In the winter of 1981, a 22-year-old Texan called Bruce was on a train through Europe. A girl boarded at Paris and sat down next to him. They started chatting, and it felt like they’d known each other their whole lives. After a while they were holding hands. When it came to her stop they parted ways with a kiss. They never traded numbers, and Bruce didn’t even know her surname. “I never saw her again, and I’ve always wished I stepped off that train,” he wrote, 40 years on, in his submission to The World Regret Survey.

It’s a website you should visit if you ever need some perspective. Set up by author Daniel Pink, it asked thousands of people from hundreds of countries to anonymously share their biggest regrets in life. It’s strangely intimate, delving into the things people wish they’d done, or not done at all, and the answers run the gamut of the human condition.

For all the people who regret cheating on their partners, there are just as many who wish they’d never married them in the first place. One 66-year-old man in Florida regrets “being too promiscuous,” while a 17-year-old in Massachusetts says “I wish I asked out the girls I was interested in.” The stories range from quotidian (“When I was 13 I quit the saxophone because I thought it was too uncool to keep playing”) to tragic (“Not taking my grandmother candy on her deathbed. She specifically requested it”).

Sometimes we feel schadenfreude when reading about other people’s failings, but there’s something about regret that is pathos-filled and painfully relatable. Flicking through the answers, many of people’s biggest regrets are the things they didn’t do. We fantasise about what could have been if only we’d moved countries, switched jobs, taken more risks, or told someone we loved them.

“It just wasn’t meant to be. I still long for the sea - and to be near the waves”.

Pink wrote a book about his findings, called The Power of Regret. “We’re built to seek pleasure and to avoid pain - to prefer chocolate cupcakes to caterpillar smoothies and sex with our partner to an audit with the tax man”, he states. Why then, do we use our regrets to self-flagellate, more often wondering “if only…” rather than comforting ourselves with “at least”?

“One of the biggest regrets I have is not moving to California after graduating college. Instead I stayed in the midwest, married a girl, and ended up getting divorced because it just wasn't meant to be. I still long for the sea - and to be near the waves,” writes one man in Nebraska. This pining reflects the rose tinted lens through which we look at what could have been. California with its rolling waves and sandy beaches is synonymous with a life of freedom, love, and joy.

Studland Beach, 1912. Vanessa Bell.

Instead of categorising regrets by whether they are work, money, or romance related, Pink has created a new system, arguing that regrets fall into four core categories: foundation, moral, boldness and connection regrets. Within these groups, there are regrets of the things we did do (often moral), and things we didn’t do (often connection and boldness regrets). The things we didn’t do are frequently more painful because, as Pink says, ‘inactions, by laying eggs under our skin, incubate endless speculation’. So you’re better off setting up that business, or asking that girl out, or stepping off the train, because of the inherently limited nature of contemplating action versus inaction.

The actions which we do end up regretting are often moral failings that fall under the umbrella of a ten commandments breach. As well as adultery, larceny and the like, there’s poignant memories of childhood cruelty. A 56-year-old woman in Kansas still beats herself up about something she did 45 years earlier: “Throwing rocks at my former best friend in 6th grade as she walked home from school. I was walking behind her with my “new” friends. Terrible.”

But regrets can have a galvanising effect, if we choose to let them. Instead of wallowing in the sadness of wishing we could rewind time, or take back something horrible we said or did, we can use that angsty feeling as an impetus for change. “When regret smothers, it can weigh us down. But when it pokes, it can lift us up,” says Pink. There’s an old proverb which has probably been cross-stitched earnestly onto many a cushion, but I still like it as a mantra for overcoming pangs of regret: “The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second-best time is today.”

Claudia Cockerell is a journalist and classicist.

Grasping at Gesture

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

Hand Catching Lead, 1968. Richard Serra.

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

In the first of these texts on gesture, I traced an unreliable and partial history of hand gestures – from roman orators and Martine Syms, to teens on TikTok and TikToks of tech bros using Apple Vision Pro – and how, somewhere along the way we lost our gestures, or lost control of them; gesticulating wildly in the open air.

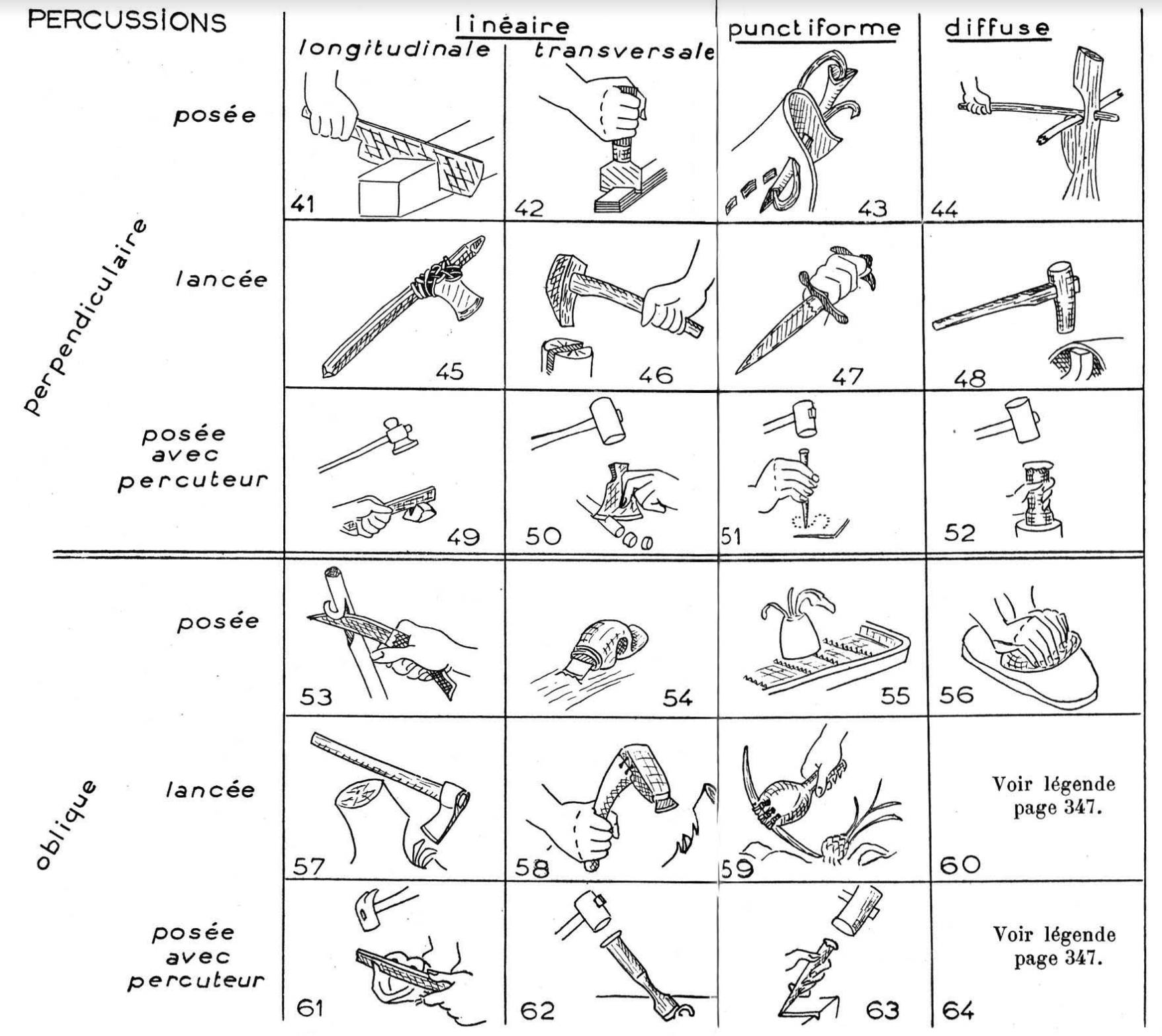

Man and Matter, 1943. Leroi-Gourhan.

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

‘The essential traits of human technical gesticulation are undoubtedly connected with grasping’¹ said Andre Leroi-Gourhan in his 1965 book, Gesture and Speech. A pioneering anthropologist, Leroi-Gourhan traced evolving relationships between hands, tools, gestures, languages, and thoughts, and developed a corresponding science for such. He is associated with Structuralist school, which means that he sought out the underlying processes (or structures) that make systems meaningful. Leroi-Gourhan’s Gesture and Speech does many things: It traces a bio-cultural evolution of postures, hands, brains, tools, art and language, up to the present day; conducts cross-cultural analysis of the rhythms and organization of human society, value systems, social behavior and techno-economic apparatus; and, amidst nascent developments in robotics and early experiments in automation, speculates on the future of our species.

“Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot.”

Alcuni Monumenti del Museo Carrafa, 1778.

The book begins with a history of the human brain and hand, with Leroi-Gourhan explaining: ‘it seemed to me that the first thing to do was to measure the results of what can be done with the hand to see what [our]brains can think.’² In pursuing both brain and hand he opposed the prevailing approach in evolution studies to focus only on the ‘cerebral’. Leroi-Gourhan was interested in how thought is embodied, how it springs from material conditions.

So, what can be done with the hand? Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot; they could grip and grasp and gesture. Now grasping is not specific to humans – qualitatively, the hand that grasps remains a relatively rudimentary device that's accompanied us across many evolutionary stages – and there are a variety of types and properties of grasps. Studying the transition from instinctive to cultural uses of hands, Leroi-Gourhan observed the functional shift from the mouth to the hand, from the hand to the grasped tool, and finally the hand that operates the machine. When it comes to grasping, ‘the actions of the teeth shift to the hand, which handles the portable tool; then the tool shifts still further away, and a part of the gesture is transferred from the arm to the hand-operated machine’. This he describes as a gradual exteriorization, or ‘secretion’ of the hand-and-brain into the tool.

But gesture still somewhat eludes us, its location ambiguous. Gesture is not in and of the hand, nor in and of the tool, rather gesture is the meeting of brain, hand and tool, the driving force and thought that sets the tool to action. To bring these gestures to light, Leroi-Gourhan developed the methodology for which he is best known: the Chaîne Opératoire.

The Chaîne Opératoire, or operational chain, is a method that makes processes visible by documenting the sequence of techniques that bring things into being – be they tangible artifacts, ephemeral performances, or even the acquisition of intangible status. Leroi-Gourhan described a technique as ‘made of both gesture and tool, organized in a chain by a true syntax’. The use of ‘syntax’ here (Structuralists had a thing for linguistics) establishes a relationship between the processes and the performance of language where there is room for both shared meaning and individual flourishes. Here, gesture, like the arrangement of words in a sentence, is relational, acquiring its shape and meaning through the interaction of mind, body, tool, material and social worlds in which it participates.

This whole time thinking about grasping hands I’ve had a film in mind: Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead, in which morsels of lead fall from above, are caught, and then released by the artist's hand. Far from mechanically consistent, sometimes Serra grasps the object, sometimes he grasps at it, narrowing missing and smacking fingers to palm. From 1968 into the early 70s Serra made a series of other hand films whose subject matter are just as the titles suggest: in Hand Catching Lead a hand, of course, catches lead; in Hands Scraping (1968) two pairs of hands gather up lead shavings which have accumulated on the floor/filled the frame; in Hands Tied two tied-uphands untie themselves.

“The creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool.. can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties.”

Hands Scraping, 1968. Richard Serra.

Curator Søren Grammel said Serra’s hand works ‘demonstrate a particular action that can be applied to a material’. I suppose that’s what the Chaîne Opératoire gets at too, as well as demonstrating how the material acts on us; in Hand Catching Lead, the lead rubs off onto Serra’s blackened hands. And just as the Chaîne Opératoire observes the network of gestures that fulfill an operation, the duration of Serra’s films cosplay pragmatism, lasting as long as it takes to complete the task (however arbitrary): How many pieces of lead can you catch or not catch until you are exhausted/cramp-up/are no longer interested? How long does it take to sweep up lead shavings or untie a knot?

Serra’s Hand Catching Lead was prompted in part by being asked to document the making of House of Cards (a sculpture where four large lead sheets are propped against one another to form the sides of a cube). But a film following the making process would, he felt, be too literal and merely illustrative. Instead, Hand Catching Lead is a ‘filmic analogy’ of the creative process. Serra knew that the creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool like the Chaîne Opératoire can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties. It seems we have come up against the limits of this approach, and of Structuralism's commitment to linguistics. Returning to Agamben, who we met in the first text: ‘being-in-language is not something that could be said in sentences, the gesture is essentially always a gesture of not being able to figure something out in language; it is always a gag in the proper meaning of the term…’³ Perhaps then Serra’s grasps are gags, grasping at lead, at air and at the irrepresentable nature of being-in-gesture.

¹ Andre Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1993) [1965]), 238

² ibid.,146

³ Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000) 59

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer, researcher and editor. She is the co-founding editor of motor dance journal.

The Six of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 11, 2024

The World card is a cosmogram, meaning it depicts the whole of the cosmos. We find a naked woman floating within a ring, her legs crossed and something flowing about her. She is Maya, the embodied force of creation and illusion. Her dancing and spinning manifests the material world. The Four Cherubs frame the corners as symbols of the states of matter…

Name: Science

Number: Six

Astrology: Mercury in Aquarius

Qabalah: Tiphereth of Vau ו

Chris Gabriel May 18, 2024

The Six of Swords is a rare positive card in the suit. Here the winds of thought are well directed, and applied with intention and effect. This is a card of knowledge, and the acquisition thereof.

In Rider, we find a ferryman guiding a skiff with a huddled woman and child. The sky is grey, and the waters before them are still. This is a card of safety and retreat, and especially in the context of the grim visages that fill the suit of Swords, this is a positive card.

In Thoth, we find six swords aimed directly at a rose within a cross. About the swords are a geometric figure, a squared circle that has formed out of the chaotic shapes fluttering about the borders. We have the purplish greys of Aquarius and the gold of Mercury. This is the cross of the Rosicrucians. This card is the mind understanding the machinations of the universe.

In Marseille, we see six arched swords and a central flower. Qabalah tells us the six of swords is Tiphereth of Vau, or the Beauty of the Prince.

The Beauty of the Prince is his science, the way he learns, understands, and applies that knowledge.

As I’ve expressed before, the suit of swords evokes Hamlet, and this is the image of Hamlet the Scientist, Hamlet the Psychologist. Seen as such, we can interpret a great deal of Hamlet’s actions as experiments; consider the Mousetrap. Hamlet hypothesizes that Claudius kills his father, he puts on a play he calls “The Mousetrap” to prove this. The play’s the experiment!

As for Rider, we can think again to Hamlet, to his general ability to survive the treacherous court, feigning madness, going unpunished for murder, making off with pirates, evading execution, etc. His death is in many ways a suicide (which we’ll see later in the suit). But clearly, his understanding of his situation allows him to survive and escape death.

Thoth shows this science applied to the rosy cross, which is the symbol on the back of all Thoth cards. The rosy cross is a cosmogram, whose arms are the four elements, and whose petals are the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. In essence, an esoteric depiction of the universe, making this card a symbol of esoteric study itself.

When dealt this card we are being given an opportunity to develop our understanding of the things around us, to create a science of ourselves, and to then apply that knowledge in our lives.

More Than Meets the Eye - 1. Light, Science, Life.

Matthew Maruca May 16, 2024

In 1917, halfway through a career of developing theories and equations that changed our understanding of the world, Albert Einstein famously said “for the rest of my life, I will reflect on what light is.”

"Spectra of various light sources, solar, stellar, metallic, gaseous, electric" - Les Phénomènes de la Physique (1868). René Henri Digeon

Matthew Maruca May 16, 2024

In 1917, halfway through a career of developing theories and equations that changed our understanding of the world, Albert Einstein famously said “for the rest of my life, I will reflect on what light is.”

Substance or energy? Particle or wave? Light is a mysterious force, which links our internal experience to the external world. Or, does it create our internal experience, from the external world?

In our basic experience, light allows us to see. From the youngest age, we come to know that the “light switch” illuminates a dark room, allowing us to experience the room, without bumping into objects, tripping over things, and hurting ourselves. The world is already there, and we are a part of it, but without visible light, our conscious experience of the world is significantly limited. And it is vastly expanded by the presence of light.

We must then ask if this biological, biochemical, photochemical phenomenon that we call “light” allows our brain to consciously experience the material world around us, or if it is light that is actually creating our experience of the world. When the light is gone, we don’t have the same experience of the world; and when it’s present, we do. So it must be - in some way - creating our experience. What then, are we actually experiencing? To answer this, we must understand what exactly light is.

Light. And Science.

From the Bible to the Big Bang, several of the most influential stories of creation start with vibration or energy, which is not light. In many religions, this is the “Word”, the Cosmic Sound “Aum”, the voice of God the Creator; in science it is simply considered vibrational energy. And then, after the vibration, there is light.

Le Monde Physique (1882). Alexandre-Blaise Desgoffe.

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night.

And the evening and the morning were the first day.”

(Genesis 1:1-5, KJV)

This Biblical account of creation, where the voice of God is speech, is sound and vibrations, and comes before light is reflected in the scientific accounts of the origin of the universe. Light did not appear until some 380,000 years after the initial “Big Bang”, and while the first photons were created shortly after the Big Bang, they were immediately re-absorbed by different particles and so the universe was “opaque” during this time. Only after the universe cooled to a temperature of around 3000K, could protons and electrons begin to combine to form hydrogen, allowing perceptible light to move freely without being immediately absorbed. And then, there was light, in the form that we see.

From the perspective of science, light is a form of energy, the result of one of the four fundamental forces (a.k.a “interactions”), which govern everything in the known universe. Light is the term we use to describe the visible range of the broader spectrum of “electromagnetic radiation”, which comprises both the light we can see, and forms of radiation we cannot see, such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared light, ultraviolet light, X-rays, gamma rays, and so on. The photons responsible for light are one of the fundamental particles created by the initial Big Bang.

It wasn’t until 1801, when a British physicist named Thomas Young performed an experiment called “the double-slit experiment”, that we began to grasp what light really is, a question we are still grappling with. Young projected light through two parallel slits in one surface, with another surface behind it. When the light hit the back surface, he expected to see a pattern showing the slits through which the light had passed. Instead, what he saw was several, spaced-out lines of light, indicating that the light traveled more like waves, canceling itself out in certain places, while becoming stronger in others. This opened up the debate as to whether light is really a particle or a wave.

It is understood that electromagnetic radiation, a spectrum that includes visible light as well as forms of radiation we cannot see, is created and emitted in the process of nuclear fusion. This began first in the origin of our universe and now occurs in stars such as our sun, when hydrogen atoms are pushed together under tremendous pressure to form larger helium atoms. Some of the matter which makes up these atoms is converted, but not created, into energy and radiated out as light.

Another common way that light is emitted is from electromagnetic interactions between energy and atoms. In a fluorescent lamp, electricity is injected into a tube filled with mercury vapor. The mercury atoms absorb this electricity but then become unstable and quickly re-emit it as mainly invisible light. This light is then absorbed by the phosphor coating on the inside of the tube, which converts it in a range that is visible to the human eye. and is then re-emitted. This process of conversion of photons with higher quantum energies into lower ones is called “fluorescence”. The energy began in the form of electricity on a copper wire being injected into the light tube (before this, it may have been energy trapped in coal, oil, or moving in the form of wind, solar, or geothermal energy, as well).

That’s just a brief summary of the science of light, what it is, and where it comes from. There is still so much we don’t understand about the nature of light but, we know, at least, that light is absolutely fundamental to our existence.

Light. And Life.

What would happen if the sun didn’t come up tomorrow or the next day and ever after? Very quickly, within days or weeks, Earth would begin to freeze. The energy of the sun provides the warmth which is a prerequisite for life on Earth but the sun offers more than warmth. The light that comes to earth powers photosynthesis—the production of all plant matter, powered by sunlight splitting water, allowing it to bind with carbon dioxide and make sugar, the basic building block of all plant matter. Without sunlight, no crops could grow and just as importantly, all of the ocean’s phytoplankton, and land’s jungles and rainforests would die, robbing the atmosphere of its oxygen. Without oxygen, complex life, which is based on energy-producing mitochondria that use oxygen to generate energy, would fail. Life on Earth is the result of the conditions provided by sunlight. Life is not just built by sunlight, but it is sustained by its power. Light is essential for keeping the “system of life” in motion.

Cloud Shadow With Red Diffusion Light During the Disturbance Period (1884). Eduard Pechuël-Loesche.

Earlier on, we established that light is a fundamental part of our conscious experience of the world. And while there are still questions as to the nature of lightself, we know even less about the nature of consciousness.The two are closely linked, and great spiritual teachers throughout history have described our consciousness as a form of energy which is either directly connected or very closely related to light.

Traditional Chinese Medicine speaks of “Qi”, the life force energy which courses through our meridians, giving us life, and, when out of balance, can lead to disease. People have practiced exercises like “tai chi” and “qi gong” for millennia to care for this energy. A very similar perspective exists in the traditional religions of India as the concept of “prana”, and practices like meditation and “pranayama” breathwork sustain, nourish, and enhance this vital “life force” energy. In the West, scientists have found tremendous benefits from meditation (a PubMed search on the term yields over 10,000 results), yet they lack clear, definite mechanisms to explain these effects. Many doctors and leading healthcare institutions are beginning to prescribe alternative treatments like acupuncture and meditation to support patients’ health and well-being. This “life force” energy may not exactly be light; it may be more like electricity. But in the same way that solar power can be converted into electricity, and electricity can be converted back into light in a lamp, these different forms of energy within us are related, even if we don’t fully understand them.

It’s clear that the existence of life on Earth is inextricably linked to the conditions given by sunlight. We could even say that life on Earth is the result of the conditions provided by sunlight. Life, as we know it, is a product of the interaction between sunlight and the elements on the Earth’s surface.

Matt Maruca is an entrepreneur and journalist interested in health, science, and scientific techniques for better living, with a focus on the power of light. He is the Founder & CEO of Ra Optics, a company that makes premium light therapy products to support optimal health in the modern age. In his free time, he enjoys meditation, surfing, reading, and travel.

What Do The Fungi Want?

Tuukka Toivonen May 14, 2024

Creative ideas grow, mutate and flourish through conversations between people. However casual or mundane, these exchanges have the potential to reveal novel possibilities, or dramatically shift the course of a fledgling idea. Direct interactions are a tremendous source of motivation for creators. The best ones possess a much-overlooked generative power…

Fly Agaric Watercolor, 1892. Leigh Woods.

Tuukka Toivonen May 14, 2024

Creative ideas grow, mutate and flourish through conversations between people. However casual or mundane, these exchanges have the potential to reveal novel possibilities, or dramatically shift the course of a fledgling idea. Direct interactions are a tremendous source of motivation for creators. The best ones possess a much-overlooked generative power.

This was the basic premise of the research I was involved in as a sociologist until, a few years ago, I stumbled across interspecies creativity. I had become intrigued by how certain colleagues – designers and artists, especially – spoke passionately about how they sought to ‘create with and for nature’ or even ‘as nature’ when making new textiles, garments or artworks. They felt strongly that it was time to start treating living organisms and ecosystems as genuine collaborators and co-creators in their process.

Atlas des Champignons (1827). M. E. Descourtilz,

Spellbound by the prospect of novel ideas and designs emerging from humans collaborating with algae, mycelium and slime mould, I started to wonder about the practical and philosophical implications of such phenomena. For me, the question was not only about understanding the material qualities of particular organisms, it was about how humans might transform themselves into genuine co-creators in relation to nonhumans.

The notion of ‘creating with nature’ can be confounding – it was for me. Beyond the crude physical barriers that keep nonhuman and human lives separate, prevailing worldviews order us to place animals, plants, insects and fungi in a fundamentally different category from humans who – whilst animal – have developed complex cultures, technologies and societies, making us ‘unstoppable’, even ‘superior’. As a result of this human-centric conditioning, we are hopelessly unaccustomed to viewing nonhuman life as intelligent. Experts of human organizational life argue that perspective-taking – in essence, making an effort to imagine the point of view of another person or persons – is key to successful communication and management, and even constitutive of our ability to be ‘fully human’. There is no such chorus calling us to seriously listen or sensitize ourselves to the perspectives of nonhumans.

To explore species-crossing creativity further (in the hope of transcending or ameliorating the non/human barrier), we decided to hold in-depth conversations with a dozen biodesigners and bioartists, as well as a few progressive entrepreneurs. The creators were growing sneakers with bacteria that produce nanocellulose, working with microalgae to purify water contaminated by fashion dyes, and sewing fabrics from wild plants, among other fascinating experimental practices.

One outspoken participant explained that, in the early stages of the creative process, he always sought to engage as directly and viscerally with a living organism as possible, relentlessly looking for promising ways to collaborate. Having developed a particular interest in working with mycelium at a mass scale, he soon became curious not only about the material co-design possibilities of this organism, but also its behaviours and its needs. A simple yet pivotal question emerged: ‘What does the fungi want?’ His next steps as a designer and entrepreneur would be derived from that simple query.

Nearly all the creators we spoke to expressed an active curiosity about the needs of the organisms they were engaging with. Working with diverse plant species as well as digital technology, one participant recounted how she explored the way plants sense the world, their sensitivity to light and sound, and their ways of communicating with other organisms. Another spoke of the profundity of learning to collaborate with organisms whose existence on earth predated that of humans by millions of years.

“By subtly observing and interacting with diverse organisms, creators can establish equality of existence with all forms of life.”

The Intruder (c.1860). John Anster Fitzgerald.

What does it mean, really, to think in terms of what a nonhuman organism ‘needs’, ‘wants’ or ‘likes’? Do such queries belie a deeper significance, an alternative way to view human-nature relations?

The visionary work of the British anthropologist Tim Ingold may help us understand why inquiring into the ‘needs’ and ‘wants’ of organisms is not just naïve anthropomorphism. In his discussion of how the people of the North American Cree Nation situate themselves in relation to their surroundings, Ingold uncovered a relevant mode of being that transcends central dichotomies that govern our (Western) thinking with regards to nonhuman life:

“From the Cree perspective, personhood is not the manifest form of humanity; rather the human is one of many outward forms of personhood. And so when Cree hunters claim that a goose is in some sense like a man, far from drawing a figurative parallel across two fundamentally separate domains, they are rather pointing to the real unity that underwrites their differentiation” (from Tim Ingold’s The Perception of the Environment, 2001).

Ingold explains that, unlike Western approaches that begin from an assumption of fundamental difference between humans and animals (leading us to search for possible analogies and anthropomorphisms, describing many animal behaviours and features in terms of their resemblance to humans), indigenous communities have typically done the opposite: starting from an assumption of similarity. For this reason, in such communities “it is not ‘anthropomorphic’ […], to compare the animal to the human, any more than it is ‘naturalistic’ to compare the human to the animal, since in both cases the comparison points to a level on which human and animal share a common existential status, namely as living beings and persons”. It is owing to this holistic worldview that the Cree assign personhood and utmost value to animals, forests, rivers and other parts of the living world, the all-important commonality with humans being their aliveness, animateness, or their potential to become an animate being.

And so we find that hidden inside our question – what does the organism need? – lies an entirely different, non-dichotomous approach to being. Indeed, by subtly observing and interacting with diverse organisms, creators can establish equality of existence with all forms of life.

It is not that we should believe that fungi or microalgae – or larger animate entities such as rivers or lakes – possess a will or preferences exactly like those of humans. Rather, it is that through these acts of curiosity and questioning, we place ourselves on a single life plane, opening up space for genuine interaction. . From this vantage point, asking ‘what does the fungi want?’, is a radical act in the context of a technological society, contesting the deep dichotomies of ‘modern’ life. Importantly, adopting this orientation rejects the totalizing tendency to position science as the only legitimate route to gaining knowledge, by restoring our ability to enter into direct, unmediated and authentic relations with other forms of life. This way of questioning can take us a surprisingly long way towards transforming ourselves into genuine collaborators and co-creators for other species.

So, what did the fungi want? In the case of the particular designer mentioned earlier, one Bob Hendrix, the answer turned out to be that they wanted to digest and recycle organic matter, specifically, humans. That insight led the designer down a path of developing mycelium-based coffins, with a view to helping humans to become useful, welcome participants in more-than-human ecosystems at the end of their lives, gifting life-giving soil with precious nutrients and energy.

Tuukka Toivonen, Ph.D. (Oxon.) is a sociologist interested in ways of being, relating and creating that can help us to reconnect with – and regenerate – the living world. Alongside his academic research, Tuukka works directly with emerging regenerative designers and startups in the creative, material innovation and technology sectors.

The World (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 11, 2024

The World card is a cosmogram, meaning it depicts the whole of the cosmos. We find a naked woman floating within a ring, her legs crossed and something flowing about her. She is Maya, the embodied force of creation and illusion. Her dancing and spinning manifests the material world. The Four Cherubs frame the corners as symbols of the states of matter…

Name: The World

Number: XXI

Astrology: Saturn

Qabalah: Tau ת

Chris Gabriel May 11, 2024

The World card is a cosmogram, meaning it depicts the whole of the cosmos. We find a naked woman floating within a ring, her legs crossed and something flowing about her. She is Maya, the embodied force of creation and illusion. Her dancing and spinning manifests the material world. The Four Cherubs frame the corners as symbols of the states of matter. This card, while containing lofty spiritual imagery, pertains to mundane material reality.

In Marseilles, our lady has a wand and a red/green sash. She is smiling and looking down. In the corners sit a winged angel, an eagle, and a lion, each of them bearing a Nimbus. Only the Bull, the Cherub of Earth, is uncrowned. The ring is a blue wreath with yellow ties, set on a pure white background.

In Rider, she has two wands and a gray, saturnine sash. She has a Mona Lisa smile and is looking down. Here the Cherubs are emerging out of clouds and have no nimbus. The ring is vegetable green with red ties and the card is set on a blue sky.

In Thoth, we have a drastically different image. World gives way to the vast Universe and the lady is no longer human, but living gold. Her sash is a serpent, and she is dancing. The Cherubs appear almost as a fountain structure, pouring fourth energy. The ring is the perspective of a round sky, the wheel of the Zodiac, and the endless stars beyond. The card is set on a resurrected Saturn, no longer dead, but verdant. The eye of God is looking down at the motions within the ring, and below is the geometric emanation of these lofty elements.

How are we to make sense of this beautiful but complex imagery?

Let’s start with a sort of spiritual “math”. Just as our journey through the Major Arcana begins with airy Zero, here we find the empty hole of the number filled in by material reality. Potential becoming actualized.

0=2, as the magicians declare. Nothing is lonely, and in it’s loneliness begets difference. By dividing itself into what we call light and dark, good and evil, night and day, masculine and feminine, it creates the tension necessary for the theater of existence.

And of course it doesn’t stop there, two makes itself four, and on and on until we have our endlessly varied World.

The sash is the serpentine, spiraling energy of creation and the direction of this divine expansion flows along

The Cherubs are the four Living Creatures of Ezekiel, the four elements, and the four fixed signs of the Zodiac. They are the divided Tetragrammaton:

The Lion is Leo and Fire

The Eagle is Scorpio and Water

The Angel is Aquarius and Air

The Bull is Taurus and Earth

These four elements, as our study of tarot will make clear, make up reality itself. We can bring this to a more scientific view, as we often struggle with differentiating the Philosopher’s elements from mundane elements.

Water is not H20, but all liquids, Earth is not dirt, but all solids, etc. The philosophical elements are states of matter and their corresponding mystical significance.

In this way, this card provides a view of all physical reality.

When we draw this card, we are often reaching a standstill, a moment of pause to look at ourselves, our actions, and our world from the distance of the heavenly machinations that form it.

Footnotes to Plato (c.428-347BC)

Nicko Mroczkowski May 9, 2024

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name…

Rafael's School of Athens, 1511.

Nicko Mroczkowski May 9, 2024

Ancient Greece was the cradle of Western civilisation. Art, agriculture, and commerce had progressed to the point of creating, apparently for the first time, a culture of intellectuals. Many of the things that we now call ‘institutions’ – democracy, the legal process, the education system – had their start in this period. It was even here that ‘Europe’ got its name.

In this flourishing new culture, thinkers began to try and understand the world in a more organised way. From this, Western philosophy was born, and science came along with it. These thinkers asked themselves: what is the world made of, and how does it work? This was not a new question, most likely every culture before had asked it in some way, but what made the Ancient Greeks unique was their systematic approach. Because they also asked a secondary question, which, arguably, is still the starting point of any scientific inquiry: what is the correct way to talk about what something is?

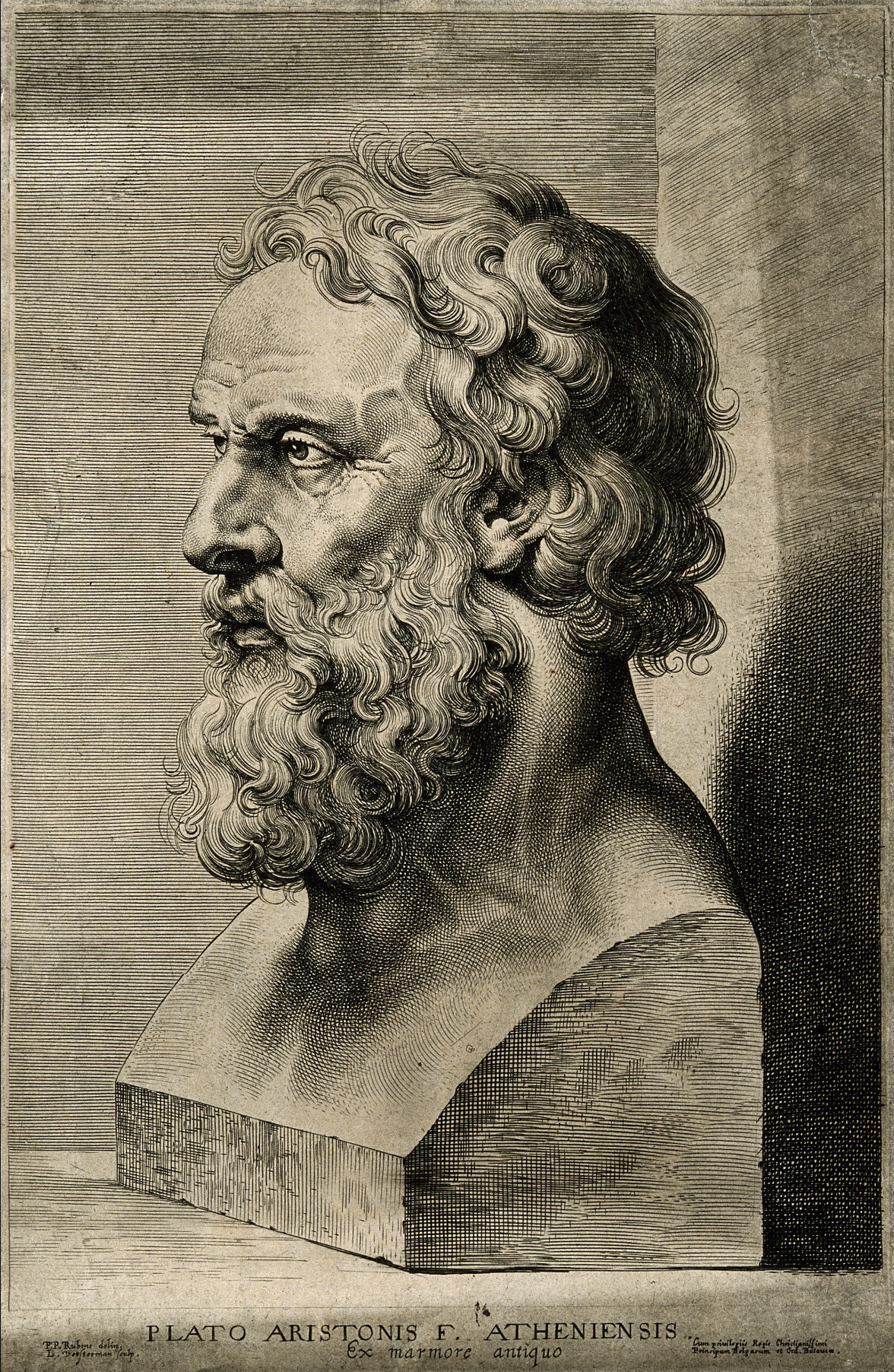

L. Vosterman, after Rubens. c. 1620.

Each of the very first philosophers answered this question with one thing: ‘substance’, or stuff. They believed that the right way to understand the world is in terms of a single type of matter, which is present in different proportions in everything that exists. Thales of Miletus, perhaps the earliest Greek philosopher, believed that all things come from water; solid matter, life, and heat are all special phases of the same liquid. For him, then, the true way to talk about an apple, for example, is as a particularly dense piece of moisture. Heraclitus, on the other hand, believed that everything is made of fire; all existence is in flux, like the dancing flame, of which an apple is a fleeting shape.

We don’t know much more about these thinkers, as not much of their work survives; most of the accounts we have are second hand. We only know for sure that each proposed a different ultimate substance that everything is made out of. Then, a little while later, along came a philosopher called Plato.

Despite its prominence, ‘Plato’ was actually a nickname meaning ‘broad’ – there is disagreement about its origin, but the most popular theory is that it comes from his time as a wrestler. His real name is thought to have been ‘Aristocles’. Whatever he was really called, Plato changed everything. Instead of arguing, like his predecessors, for a different kind of ultimate substance, he observed that substance alone is not enough to explain what exists: there is also form. In other words, he more or less invented the distinction between form and content.

One could spend a lifetime analysing these terms, and there are whole volumes of art and literary theory that address their nuances; but it’s also a common-sense distinction that we use every day. The form of something is its shape, structure, composition; the content, or substance, is the stuff it’s made of. So the form of an apple is a sweet fruit with a specific genetic profile, and its content is various hydrocarbons and trace elements. The form of a literary work is its style and composition – poetry or prose, past or present tense, first- or third-person, etc. – and its content is its subject matter, what it describes and what happens in it.

An attempt at a classification of the perfect form of a rabbit. (1915)

We can already see Plato’s influence on modern knowledge in these examples. The correct way to talk about something, for him, was primarily in terms of its form, and only secondarily in terms of its substance. This is still the case for us today. There is a powerful justification for this preference: it allows us to talk about things generally. This is basically the foundation of any science; we would get absolutely nowhere if we only analysed particular individuals. There are just too many things out there. No two animals of the same species, for example, will ever have exactly the same make-up – even if they’re clones. They have eaten different things, had different experiences; they also, quite frankly, create and shed cells so rapidly and unpredictably that differences in their substance are inevitable. What they do have in common, though, is their anatomy, behaviour, and an overall genetic profile that produces these things.

Forms are peculiar, however, because they don’t exist in the same way as substances do. While there are concrete definitions of substances, the same cannot be said for forms. There are, for example, no perfect triangles in existence, and we could probably never create one – zoom in enough, and something will always be slightly out of place. So how did Plato come up with the idea of something that can never be experienced in real life? The answer is precisely because of things like triangles. Mathematics, and especially geometry, is the original language of forms, and it can describe a perfect triangle or circle, even though one may never exist. The success of mathematical inquiries in Plato’s time allowed him to recognise that the concept of forms which worked in geometry can be applied to understand the world more generally.

Forms are perfect specimens of imperfect things, are exemplars, or things we aspire to – they are the way things ought to be, in a perfect world. ‘Form’ in Plato’s work is also sometimes translated as ‘idea’ or ‘ideal’. And so, Plato’s answer to the question of how to conduct scientific inquiry was this: the correct way to talk about something is in terms of how it should be. Despite our imperfect world, rational thinking – the capacity of the human mind for grasping things like mathematical truths – can do this, and that’s what sets human beings and their societies apart from the rest of nature.

Perfect Platonic Solids

It gets a little strange from this point on: Plato believes that forms really exist, but in a separate, perfect world. Our souls start out there and then make their way to the material world to be born, but still have implicit knowledge of their original home, and this is where reason originates. Improbable, yes, but not completely absurd. Plato was clearly trying to explain, to a society that was just beginning to understand the importance of perfect knowledge, how it could exist in our imperfect world of change and difference. Two millennia later, Kant would show that it’s due to the way the human mind is structured, but we don’t really know how this happened either.

Really, we’re still playing Plato’s game. The basic realisation that to know the world, we must study the general and the perfect, and ignore the non-essential characteristics of particular individuals – this is his legacy. Of course, this way of thinking is so deeply ingrained in Western culture that it can be hard to grapple with; it’s so fundamental that we take it for granted. But what we call knowledge today would not be possible at all without it. Seeing this, we can imagine what the influential British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead meant when he wrote that ‘the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists in a series of footnotes to Plato’.

Nicko Mroczkowski

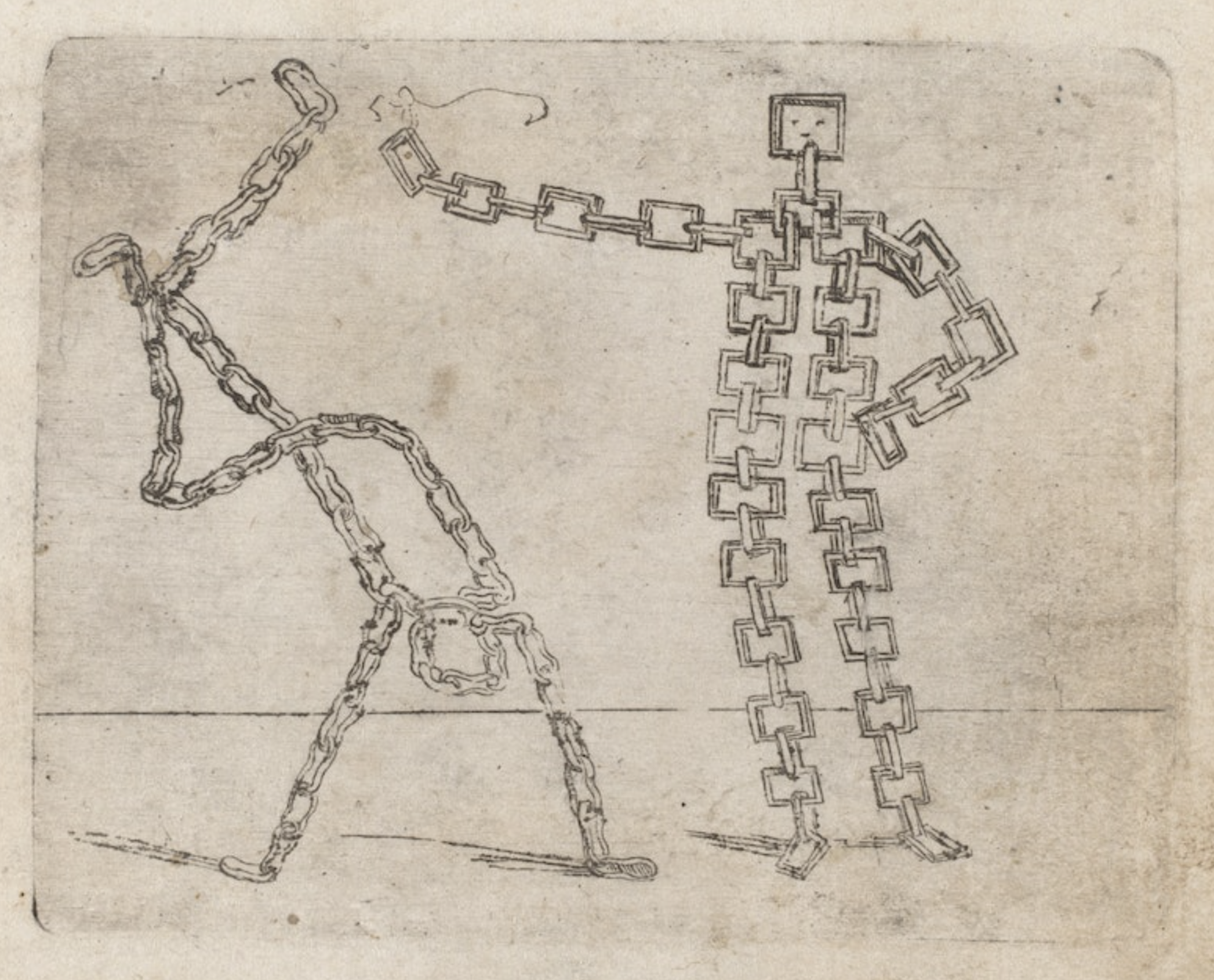

Children’s Drawings

Ale Nodarse May 7, 2024

Children’s drawings abound. They have few dates and fewer titles, but nonetheless they pile up. Assembled on fridges or tucked away in shoeboxes, they belong to a world of their own. It’s a world they, with few inhibitions, create –– and a world which is fragile. If such drawings survive, it’s most often because they have been saved by someone else. In other words, if drawings from your childhood survive, then you most likely have someone to thank…

Ale Nodarse May 7, 2024

Children’s drawings abound. They have few dates and fewer titles, but nonetheless they pile up. Assembled on fridges or tucked away in shoeboxes, they belong to a world of their own. It’s a world they, with few inhibitions, create –– and a world which is fragile. If such drawings survive, it’s most often because they have been saved by someone else. In other words, if drawings from your childhood survive, then you most likely have someone to thank.

Children’s drawings may be quaint, but they are powerful, too. In Bologna, in 1882, an Italian archaeologist and art historian called Corrado Ricci took shelter from the rain beneath a covered archway. That portico, to Ricci’s amazement, was filled with adolescent scribblings, with graffitied words and drawings. Here was a “permanent exhibition of literature and art” — one of rare modesty and more than occasional impropriety¹. The exhibition moved him and led him to collect children’s drawings, assembled in a book titled ‘The Art of Children’ (L’arte dei bambini). Lamenting the drawings’ anonymity, Ricci was determined to trace their history. The Art of Children is replete with works from his collection. It charts a course from first lines to full figures and makes a case for the life of a child’s mind. It charts, as well, the beginnings of a particular branch of developmental psychology. One in which, for instance, a “Table and Chair” becomes a proof of spatial cognition; and where a quickly dashed “Sun” rises in attestation as if to say: Observe the work of a child, year six.²

Human children have drawn for millennia (and so, quite likely, did their neanderthal cousins)³. Remarkable though it is, this fact ought not surprise us. Ricci’s revelation, that such drawings have much to teach us, did however seem surprising (at least to many of his peers). Turning away from the product of children’s drawing to the process of its collection (on the fridge or in the shoebox), we might wonder: What causes us to marvel at a child’s drawing in the first place?

This act of marveling has a history. One of the earliest images of a child’s drawing was not by a painter, but by an archaeologist and antiquarian. That painting, Giovanni Caroto’s c. 1515 Portrait of a Boy With Drawing, is marvelously strange.⁴ Strange, given that children were rarely depicted apart from their parents — as having their own distinct lives.⁵ And stranger, still, because this child holds a drawing. Curving slightly at the grasped edge, the paper reveals a standing figure, a partial head, and, just above the boy’s thumb, an eye placed in profile.

Why set such a drawing in painting? Scholars have sought a familial link between the artist and the boy.⁶ His carrot-colored hair has provoked speculation that he is indeed the artist’s son (or younger nephew), namely since Caroto means “Carrot.” But Caroto’s other vocation remains suggestive. As an archaeologist, he spent years compiling a list of the antiquities in his hometown of Verona, tasked with the setting of “timeless” fragments back into time.⁷ Viewed as testimonies of human creation, every fragment –– drawn and discovered –– could be beheld as eloquent. Whether made by his relative or not, Caroto found the boy’s drawing worthy of similar preservation.

Children’s drawings, a marvel in their own right, raise a question that children do not ask. What do we — looking back, looking ahead — consign to loss? And what do we save?

¹Corrado Ricci, L’arte dei bambini (The Art of Children) (Bologna: Zanichelli, 1887), 3–4.

²Helga Eng, The Psychology of Children's Drawings: From the First Stroke to the Coloured Drawing (London: Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., 1931). (Fig. 62, reproduced from her text.)

³Jean-Claude Marquet (et al.), “The Earliest Unambiguous Neanderthal Engravings on Cave Walls: La Roche–Cotard, Loire Valley, France,” PLoS ONE (2023): 1–53.

⁴The painting, made with oil on board, is kept at the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona, Italy.

⁵Phillipe Ariès, Centuries of Childhood, 43. Ariès proposed, not without significant controversy, that the turning point for the representation and understanding of the child as such was the beginning of the seventeenth century. .

⁶Francesca Rossi (et al.), Caroto (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2020), 134.

⁷Caroto captured Verona’s antiquities through a series of engravings first published in 1540, with a text by antiquarian and humanist Torello Saraina.

Alejandro (Ale) Nodarse Jammal is an artist and art historian. They are a Ph.D. Candidate in History of Art & Architecture at Harvard University and are completing an MFA at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art. They think often about art — its history and its practice — in relationship to observation, memory, language, and ethics.

Strength (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 4, 2024

Strength depicts a woman with power over a lion. She has overcome this extremely dangerous beast by means of influence and control, though each deck posits a very different form of control…

Name: Strength, Force, Lust

Number: XI or VIII

Astrology: Leo

Qabalah: Teth ט

Chris Gabriel May 4, 2024

Strength depicts a woman with power over a lion. She has overcome this extremely dangerous beast by means of influence and control, though each deck posits a very different form of control.

In Marseilles we find a well-dressed noble woman opening the mouth of the lion. She is smiling. While one hand is opening his mouth, the other is in front of it, revealing her degree of control. The lion’s eyes, like his mouth, are wide open, he looks up as she looks down. The card is called “La Force”, the force being that bestial force of the lion, and the taming, civilizing, force of the woman.

In Rider, we see a similar image. Our lady here is dressed in white and adorned with flowers. She is crowned by infinity, an explicit mirroring of the hat in Marseilles. The lion here is far more tame, almost reduced to a dog, licking at her happily, with his eyes closed. She is closing his mouth. This card is called Strength, which is the strength of the woman to close the lion’s mouth, and of course, the physical strength of the lion himself.

In Thoth we are given a drastically different image, and evocative name, Lust. Here we have a reinterpreted scene from Revelation: the Whore of Babylon and the Great Beast. Moving beyond the repressive, chaste attitudes of the past two cards, here the woman controls the lion from on top. She has reigned the beast, and rides him. She is naked and bearing a cup, and the beast not only has many faces, but a serpentine tail (the Serpent is the ideogram of Teth).

The profound differences across these decks reveal just how significant this particular card is.

This is a card about Sex. Of course one can interpret these means of control as they appear in relationships, but this is a mystical art, and the important work here is understanding how this relates to self control.

The Freudian Libido, immense and dangerous, is given an emblem here. In the past, repression or chaos were our only options for dealing with this energy.

We tame the beast, or we are devoured by it. The radical, psychoanalytic development of sublimation, is shown in Thoth. Here we are given the option to not simply repress and subdue our animal urges, but to ride them where we will. Primal drives are the most powerful forces of nature, effectively directing them means harnessing a great power. Yet, this is difficult and dangerous thing, so much so that we even have a phrase for it: riding the tiger.

This is a card of creative and developmental energies, how they can overwhelm us, and how to understand and utilize this overflow.

When dealt this card, we are to consider our own creative energies, our sexuality. One can often expect an influx of these! And how will you deal with it? Use force to tame it, spiritual strength to control it, or ride the tiger of lust?

Boltzmann Brains — 1. Chaos in the DVD

Irà Sheptûn May 2, 2024

If you want to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe…

Celestograph, 1893. August Strinberg.

Irà Sheptûn May 2, 2024

“If you want to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.” Carl Sagan

Let’s pretend it’s 2006. You’ve just come back from the kitchen to continue watching a movie on DVD. The screen has now faded to black and the DVD logo is bouncing slowly from wall to wall in the box of the screen. You observe over time, the logo hits many different points within the rectangle of the box. One wouldn’t be alone in wondering how often the DVD logo will lock perfectly into one of the corners of the screen before bouncing back again. Naturally, this varies depending on the pixel size of the screen as well as the logo itself and its fixed velocity, but for a standard NTSC-format DVD Player with 4:3 aspect ratio, we can approximate the phenomenon to occur roughly every 500 – 600 bounces, or once every 3 hours. Now, suppose we blew up our screen slowly to the size of the observable universe, how often would we score a perfect corner lock-in then? The idea becomes completely absurd: we can all safely agree the probability is inconceivably, astonishingly tiny. But not impossible.

Celestograph, 1893. August Strinberg.

In the latter half of the Nineteenth Century, physicists were busy laying the foundations of what we now understand as statistical thermodynamics – the art of using the rules that govern the very small components of a system that are probabilistic in nature, to build up a clear picture of the system’s behaviour in general. These small components (individual particles amongst many) have position and momenta that are constantly changing. It is useful to think of a closed system as a new deck of cards, with each particle represented by a single card in the deck. A central concept of statistical thermodynamics is entropy, often synonymous with disorder, where higher entropy systems are subject to greater randomness and uncertainty in their behaviour. If I were to take a random card and place it somewhere else in our new deck as you observed, you’d probably have an easier time reverting the deck back to its original order than if I shuffled it thoroughly. You might say the one-card rearrangement is of lower entropy than the thoroughly shuffled deck, due to the degree of disorder inherent to the shuffling of the cards from their standard order, right? Well, you’d be correct! There are many more possible configurations in our higher entropy shuffled deck that are all equally likely compared to any one-card manoeuvre. However, this description of entropy as a measure of disorder can often be misleading, as we’ll soon discover.

Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann, who alongside his contemporaries, was concerned with understanding how the properties that define the state of a closed system (such as average energy, temperature, or pressure) could be interpreted from the more probabilistic behaviour of the individual particles that make up a given thermodynamic process. The Second Law of Thermodynamics says that the entropy of a closed system can only stay constant or increase over time. Boltzmann contested that perhaps entropy could be thought of more as a statistical property – the chances of staying the same or increasing are high, however the chances of decreasing are not zero, subject to behavioural fluctuations in the particles of the system. Recall our shuffled deck of cards: it’s highly unlikely to return to its original order through constant random shuffling, but the possibility must occur with infinite time!

“The system experiences a fluctuation to lower entropy; an ordered state arising from a more disordered one.”

One might now see how the description of entropy as a measure of disorder can cause some problems. Let’s say we have a deck of cards arranged by suit, and another arranged by increasing number. Which is more inherently entropic? Both decks are undeniably examples of a certain order within their own closed systems. If we accept that both are rearranged from the same initial structure, one must have higher entropy than the other to account for the number of rearrangements to get the structure it is now in. In this way, we can properly define entropy as a measure of the number of ways you can arrange these particles without changing the overall state of the system. In other words, how many ways can I shuffle the deck without adding new cards or taking any away?

Celestograph, 1893. August Strinberg.

But wait! Aren’t these so-called entropic fluctuations to order not a gross violation of the Second Law? If entropy is a statistical property, these fluctuations become inherent to the nature of the Second Law and not a violation, because the net direction of entropy will still tend to increase. Returning to our DVD Player (assuming that the little DVD logo travels around the box with random motion) we can say our closed system will increase in entropy as with every wall bounce the DVD logo makes as it loses predictability in its path. Over infinite time, all possible positions of the DVD logo in the two-dimensional box will be true, and shall increase steadily in entropy with every bounce.

But what of our exciting statistically improbable instances where the logo perfectly locks into a corner? According to Boltzmann, in these instances, the system experiences a fluctuation to lower entropy; an ordered state arising from a more disordered one. However, this is all still outweighed by the increasing net entropy of our DVD Player; the energy used up to power our little dancing logo on its journey of increasing uncertainty, and the heat expended by its humble efforts’ ad infinitum. With this same reasoning, Boltzmann introduced new ideas around the nature of our early universe and how it came to be well before the formulation of Lemaître’s theory of the Primeval Atom, or as it’s now known, The Big Bang Theory.

Now, try to imagine a vast cosmos, infinite in age. All the different regions of this system have more or less reached an equal share of energy: it is uniformly distributed, or what we call in Thermal Equilibrium. At this stage in the lifecycle of a cosmos it has reached maximal entropy, or Heat Death. As we know, it’s not impossible for such infinitely large systems to experience large fluctuations. Given the infinite age of this cosmos, any statistically unlikely event (no matter how improbable) must be true. It is not impossible that one of these local regions in space and time might fluctuate just enough from maximal entropy to form a new ‘world’, if only for a short period of aeons. This new ‘world’ might be indistinguishable from the world that you and I live in; a lower-entropy state of unspent energy and potential, arising by sheer improbability, from an otherwise vast and dead cosmos, trapped in maximal entropy.

There is a chance, then, that we are ‘the moment’ in the truest sense of the term. Could we be special and lucky enough to exist within such an unlikely ‘new world’? Could ours be the moment the DVD logo locks perfectly into the corner of the screen - a Boltzmann Universe?

Nonviolent Communication - Our Brains, Stereotypes, and Strategies

Wayland Myers April 30, 2024

Fifteen years ago, learning that I'd written a book on Nonviolent Communication, my wife's Community Nursing professor asked if I would come to the community clinic and share some of what I knew about NVC with a small group of men. They were beginning the process of reintegrating themselves into civilian life after having completed multi-year prison sentences and a six-month stint in halfway houses. The evening was part of a support program made available to them and I was keen to share some of the wisdom and humanity I’ve derived from this unique framework for helping people create compassionate connections with others and themselves.I readily agreed...

Fragment from an 18th Century Memento Mori, Poland

Wayland Myers April 30, 2024

Fifteen years ago, learning that I'd written a book on Nonviolent Communication, my wife's Community Nursing professor asked if I would come to the community clinic and share some of what I knew about NVC with a small group of men. They were beginning the process of reintegrating themselves into civilian life after having completed multi-year prison sentences and a six-month stint in halfway houses. The evening was part of a support program made available to them and I was keen to share some of the wisdom and humanity I’ve derived from this unique framework for helping people create compassionate connections with others and themselves.I readily agreed.

When preparing for talks like this one, I think about the particular audience I'll be speaking with and try to imagine which parts of NVC they might find interesting and relevant. When I thought about what to share with these men, I drew a blank. I also unhappily discovered that when thinking about the evening with them, I felt anxiety about how the evening might go far more than I usually do. What was going on?

It wasn’t until recently, when in preparation for writing a new book on NVC of which these articles are a part, that I explored the most recent findings concerning how our brains work and discovered that the strength of my anxious feelings wasn’t my fault. Particular brain structures and neurological processes that bestowed the most survival and reproduction advantages to our ancestors had kicked in. Without my conscious involvement, my brain had, in an instant, automatically performed a safety assessment using whatever information concerning people who’d been in prisons I absorbed up to that point in my life. The problem was,having never met someone who had done a multi year prison sentence, the only information my brain had to work with was whatever I’d seen in movies, TV, documentaries, and the media. Oh boy! The more primal parts of our brains go to work even before we become consciously aware of things, and they aren’t sophisticated enough to discern the difference between reasonably reliable information and total fictions. As a result, mine had created a stereotype of “these types of men” that it felt was accurate enough to sound the prophylactic alarms (generating feelings of anxiety). This was not the mental and emotional energy I wanted the men to encounter when I met them. My dream was for them to have the happy surprise of meeting someone who was open-minded, respectful, and had no pre-existing prejudices. But back then, I just criticized myself for not being a very good practitioner of what I was trying to teach.

“To view another through the lens of the stereotypes, activated emotions, or moralistic appraisals is like putting on glasses whose prescription is designed to help you find the evidence that confirms your prejudicial views”

In the practice of NVC stereotypes, preconceptions, and any other ways that we formulate or work from assumptions about the “type” of person another is are barriers. They make it much more difficult to practice the “in-to-me-see” part of NVC, which is its heart, and where its power to calm conflict and facilitate mutually beneficial relationships comes from.

To view another through the lens of the stereotypes, activated emotions, or moralistic appraisals is like putting on glasses whose prescription is designed to help you find the evidence that confirms your prejudicial views and the emotions offered up by your primal brain to try and keep you safe. Good luck creating mutually enriching connections wearing those glasses.