The Could-Have-Beens

Ale Nodarse June 13, 2024

Art has a name for the path not taken: the pentimento. The word is Italian, and it is usually preserved as such in English…

“Saint Paul, Hermit”, Salvator Rosa, Mid-seventeenth-century. Pen and brown and black ink with wash.

Ale Nodarse June 13, 2024

Art has a name for the path not taken: the pentimento.

The word is Italian, and it is usually preserved as such in English. (Although, if you fancy Victorian novels, you might just stumble upon the now demoded “pentiment”). A 1611 English-Italian dictionary provides an initial translation:

Pentimento: repentance, penitency, sorrowing for something done or past.¹

The primary focus is regret. The word’s original context was a religious one: the act of repenting for one’s sins. Outside the religious sphere, however, a pentimento might be described more generically: as the ability within us “to change one’s mind” or “to have a change of heart.”

In analyses of painting and drawing, however, the term took on another meaning. The pentimento came to describe any visible alteration to a work of art: any moment where the artist visibly changed her mind. Drawn pentimenti (the plural form of pentimento) allow us to follow the artist’s process, to trace ideas (half-) formed. With each pentimento, we follow a maze of creative possibility — without the risk of getting lost.

Certain artists capitalized on these marks, turning erstwhile mistakes into a litany of meandering forms. In a drawing of Saint Paul (above), by the Italian artist, actor and poet, Salvator Rosa (1615–1673), the Biblical hermit appears in a state of bewilderment. He is (the trees tell us) in the wilderness, but it’s his flailing arms that signal wild. Looking closely at the drawing, we can follow the artist’s moves: all of those blurred limbs, so many pentimenti, stretching out below the final pair of fully raised hands. The effect is cinematic.

Saint Paul was defined by his repentance. He lived alone in the desert. He survived on crumbs — brought by a raven, the story goes — and prayer.² In Rosa’s image, however, repentance finds another form. The artistic definition comes into play as pentimento changes from sorrow to possibility, from a penitential gesture to a dazzling abundance of could-have-beens: to multiverses in ink.

No doubt, all of these marks could cause confusion. One seventeenth-century critic likened this compositional style to a “mass of sardines in barrel,” or, worse, a “market of maggoty nuts.”³ But a certain beauty, in all its perplexity, resides in this memorialization to the vagaries of journeys, embarked or imagined.

And so, if we allow it, the pentimento asks. Can we still marvel, without regret, at all the paths not taken?

¹Giovanni Florio, A Worlde of Wordes (London: Arnold Hatfield, 1598/1616), 366.

²This was also depicted in images. See, for example, Saint Paul the Hermit Being Fed by a Raven, an oil painting by an anonymous Spanish artist in the Wellcome Collection, London.

³Marco Boschini, The Map of Painterly Navigation (La Carta del Navegar Pitoresco), translated in Philip Sohm, The Artist Grows Old: The Aging of Art and Artists in Italy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 125. Boschini, a Venetian, pointed his critique at artists in seventeenth-century Florence.

Alejandro (Ale) Nodarse Jammal is an artist and art historian. They are a Ph.D. Candidate in History of Art & Architecture at Harvard University and are completing an MFA at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art. They think often about art — its history and its practice — in relationship to observation, memory, language, and ethics.

A Brief History of White Magic. II, From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance.

Flora Knight June 11, 2024

The Medieval period heralded the start of the modern conception of witchcraft, shaping how we imagine it today. As Roman civilization collapsed into barbarism, the period from the Dark Ages to the High Middle Ages remained muddy and obscure, but two prevailing ideas emerged: the magical quest and spiritual alchemy…

A Rosicrucianism seal, dense in magical symbolism.

Flora Knight June 11, 2024

The Medieval period heralded the start of the modern conception of witchcraft, shaping how we imagine it today. As Roman civilization collapsed into barbarism, the period from the Dark Ages to the High Middle Ages remained muddy and obscure, but two prevailing ideas emerged: the magical quest and spiritual alchemy. This era also saw the rise of 'witches'—folk healers using natural ingredients and traditional remedies that later informed the stereotypical witch. Alchemy, botanical mysticism, and, towards the end of the High Middle Ages, Dante’s "Divine Comedy" and the profound vision of the universe it created established a magical world that perseveres today.

Witchcraft and white magic during this time existed as a niche practice, a hangover from paganism and the 'Old Religions.' It is difficult to judge exactly how much magic was integrated into society, but there are several notable examples of its continued existence. Chartres Cathedral is rife with alchemical statues, magical imagery, and mathematical structures that point towards ancient and early Christian magic. There is also scholarship relating the rise of Gothic architecture, with its Pythagorean mathematical structure, to an ongoing interest in and practice of magic, especially among building groups such as the stonemasons and freemasons. Green Men statues, figures made out of natural material such as leaves or twigs, also pervade many churches of this time in England. Nature festivals such as maypole dances all point to magic being a continued part of life, not fully embraced but not completely rejected by the church. The alchemical process was also adapted into the understanding of the human psyche—alchemy was a way to realize a higher power, with the fastest route to this being through the earth. A naturalist and magical combination—witchcraft and herbalism—led to a higher plane of existence.

Four depictions of Saturn from an illustrated manuscript of Picatrix.

Healers were also prevalent, though they existed outside of official medical practices. Doctors of the time were learned and studied Aristotle and Galen, 'scientific texts' rather than indigenous practices, but the actual effect on the patient of these two approaches was nearly identical, so it came down to wealth and preference. Herbs, plants, tinctures, and potions were widespread, and though mostly passed down orally, there are a number of examples of written texts. The most important of these is the "Picatrix," a book of magic and spells originally written in Arabic, most likely in the 10th century. It contains numerous recipes for herbal and magical medicines as well as incantations.

A Spell From Picatrix

O Master of sublime name and great power, supreme Master; O Master Saturn: Thou, the Cold, the Sterile, the Mournful, the Pernicious; Thou, whose life is sincere and whose word sure; Thou, the Sage and Solitary, the Impenetrable; Thou, whose promises are kept; Thou who art weak and weary; Thou who hast cares greater than any other, who knowest neither pleasure nor joy; Thou, the old and cunning, master of all artifice, deceitful, wise, and judicious; Thou who bringest prosperity or ruin, and makest men to be happy or unhappy! I conjure thee, O Supreme Father, by Thy great benevolence and Thy generous bounty, to do for me what I ask…

The final major element of Medieval witchcraft is Dante’s "Divine Comedy." A synthesis of High Medieval culture, in which orthodox science and religion combine with white magic and ancient mystical religion. As briefly as possible, for perhaps no single text in history has as much scholarship, Dante is important to witchcraft in many ways. The “Divine Comedy” solidified a celestial and zodiac way of thinking, showed a path to a higher plane through the soul and introspection—the true purpose and essence of all white magic. It depicted the whole spectrum of human consciousness in terms of love—an all-inclusive system. This system was adapted and existed in the sorcery of the time. Where all good and bad in Dante’s world come from love, in sorcery or witchcraft all came from the Prima Materia, or first material. Prima Materia is ill-defined in contemporary works, but it is not unfair to suggest that sorcery even at this time was used as much as a philosophical framework to see the world as any sort of scientific process.

Witches Sabbath, Goya. 1798. Depiction of a renaissance witch cult.

The Renaissance, running roughly from the mid-15th to the early 18th century, was the most bountiful time regarding magic and witchcraft, for both good and bad. Before examining how white magic developed during this time, it is important to consider how it was persecuted and repressed. This was the time of the witch trials and the beginning of the ‘Old Hag’ understanding of witchcraft. Almost all of this can be attributed to a single book—"Malleus Maleficarum" by Heinrich Kramer—published profusely in the latter half of the 15th century. Prior to this, witchcraft was frowned upon by the Christian church but not treated as much more than a small pseudoscience that caused little harm. Kramer, however, argued that witchcraft was a communing with the devil and should be punished by death, with confessions extracted by torture. The entirety of the witch trials can be attributed to this work, and in the period that followed, thousands of women were brutally murdered and tortured. Modern scholarship suggests that almost none of these women were practicing modern or contemporary witchcraft, a malevolent act, though some would have been indulging in rituals of white magic. It is also important to note that the figures in magic at this time were mostly men. It was a deeply patriarchal society, and though we have records of women using magic, these come almost exclusively from the witch trials, where the magic recorded as being used, entirely under coercion and torture, was black magic, fall less prevalent in society than the white magic that quietly permeated across the culture.

“He was devoted to the planets and the natural healing magic of them and the earthly world that represented them, but he emphasized that he was simply amplifying natural forces.”

While the witch trials were flourishing and popular thought was turning against magic, important developments were happening in Italy and across Europe. Marsilio Ficino was hired by Cosimo de Medici to translate ancient texts, reflecting the Renaissance obsession with Ancient Greece. During this period, he discovered a Hermetic text, the "Corpus Hermeticum." This was an important magical text that contained spells, incantations, and, most influentially, astrological readings that integrated characteristics and healing into the conception of the zodiac. As the public tide turned against sorcery and witchcraft, Ficino was careful to present the text as natural magic rather than angelic or demonic magic, avoiding any response from the Church. Ficino used astrology in medicinal ways, creating talismans, culling plants and herbs, and contemplating symbolic imagery. He was devoted to the planets and the natural healing magic of them and the earthly world that represented them, but he emphasized that he was simply amplifying natural forces. This work laid important groundwork for modern magic. Pico della Mirandola took the ideas of Ficino and added the invocation of spirits. Though these two figures contributed enormously to the 20th-century flourishing of magic, during their time, it remained in the realm of the intelligentsia, and the public conception of magic remained as it was in Medieval times, with herbal medicine, love philtres, and charm spells still at its center.

Rosicrucianism arose at this time, a magical brotherhood from whom most modern beliefs and theories of white magic originated. A series of pamphlets published in the early 17th century marked the beginning of this new order with a story of the mysterious C.R. C.R had travelled far across the world to the Holy Land, meeting magical leaders in each country and learning much from the Turks in Damascus. He returned to Europe and formed an order that followed these six rules:

The Temple of the Rose Cross, Teophilus Schweighardt Constantiens, 1618. Magical depiction of a Rosicrucianist clubhouse.

1. None should profess to any other vocation than to cure the sick.

2. There will be no distinctive habit or clothing.

3. There will be meetings every year at their headquarters.

4. They will find a worthy person to succeed them upon their death.

5. The word C.R. will be their mark, seal, and character.

6. The order will be kept secret for 100 years.

They took their symbolism from alchemical treatises and the trump cards of the Tarot, and their magic was a benevolent one, using mathematics, mechanics, Qabalah, and astrology for scientific gain. Much of sacred geometry came from Rosicrucianism, with their headquarters informed by the Temple of Solomon, geomancy, and magical mathematics. Their significance lies in being a secret order devoted to magic, with influence across society. Rosicrucianism remained at the heart of magic for centuries, informing societies across the western world right up the ‘The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn’ and Aleister Crowley. It marked a conclusion to the centuries long journey white magic had taken, removing it from an oral tradition and folk practice into an organised and formalised order.

Flora Knight is an occultist and historian.

The Three of Disks (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel June 8, 2024

The Three of Disks is the beginning of material development in the suit of Disks, making it a very beneficial card. This is a card of labor and hard work, of laying the foundation for something great; the molehill that will become a mountain…

Name: Works, The Three of Disks

Number: 3

Astrology: Mars in Capricorn

Qabalah: Binah of He ה

Chris Gabriel June 8, 2024

The Three of Disks is the beginning of material development in the suit of Disks, making it a very beneficial card. This is a card of labor and hard work, of laying the foundation for something great; the molehill that will become a mountain.

In Rider, we see a craftsman, a monk, and an artist. They are working on a cathedral, beautifying a base structure. The column of the cathedral is mounted by the three disks. Each figure is doing their part, the monk overseeing, the artist designing, and craftsman realizing the design in stone.

In Thoth, we see three wheels forming a three faced pyramid. The wheels are the red of Mars, and the surrounding indigo is the Earth of Capricorn, moving almost cymatically. In the center of each wheel we find a symbol. Salt, Sulphur, and Mercury.

These are the three Alchemical Principles, the masculine Sulphur, the feminine Salt, and the androgynous Mercury..

We find this trinity reflected in the majors where the Magician is Mercury, and the Emperor and Empress are Sulphur and Salt. This trinity is what allows for the materialization occurring in the card. This is “Blood, sweat, and tears”.

In Marseille, we find two disks being surmounted by a third. This is the image of a sprout arising from the earth. Qabalistically, the card is the Binah of He, or the Understanding of the Princess.

The Understanding of the Princess is Work. Work is the condition of all material development. Even when we feel as if things “fall into our laps” colossal work had to occur beforehand. As William Blake says, “To create a little flower is the labor of ages.”

This card is that labor. And on the scale of ages, the little flower differs not from the cathedral.

Being Mars in Capricorn, this is the foundational groundwork that it takes to create and reach great heights. Mars is the aggressive action, and Capricorn is the Goat who scales the mountain.

The Alchemical Principles are all vital parts of this creative process, the macrocosmic display of Thoth is brought down to humanity in Rider. The Monk guides what the artist envisions, what the artist envisions the craftsman materializes. We contain all three of these within ourselves.

One can almost envision the disks as gears, turning one another, if one is stuck, or smaller than the rest, the work cannot function. One can apply this to teamwork as well.

When dealt this card, we are being asked to labor, to work toward something great, to materialize our visions, and to refine our creative process.

More Than Meets the Eye - 2. Health and Light.

Matthew Maruca June 6, 2024

So, we understand that light doesn’t just allow us to see by illuminating the world, it is the very thing that allows us to live within this world. Light is the energy source that powers all life on earth, and if it causes us to be alive, what else might it be doing to us? What follows is a brief and incomplete overview of the last 150 years of studies of light, and the crucial role in our physical and psychological well being it plays…

C. Reithmuller Lantern, Chromolithograph. c.1890.

Matthew Maruca June 6, 2024

So, we understand that light doesn’t just allow us to see; by powering the evolution of living organisms, and their various functions, light actually caused the process of vision to exist. . If light is powering our existence, what else might it be doing to us? What follows is a brief and incomplete overview of the last 150 years of studies of light, and the crucial role in our physical and psychological well being it plays.

Light. And Health.

Florence Nightingale, considered the founder of modern nursing, observed in the mid-nineteenth century: “It is the unqualified result of all my experience with the sick, that second only to their need of fresh air is their need of light; that, after a close room, what hurts them most is a dark room, and it is not only light but direct sun-light that they want... People think that the effect is upon the spirits only. This is by no means the case. The sun is not only a painter but a sculptor.” (Notes on Nursing, 1860)

In 1903, the Danish physician Niels Finsen was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine for his discovery that ultraviolet light was an effective means to treat lupus vulgaris (tuberculosis of the skin) due to its antibacterial effects.

Florence Nightingale.

In the early years of the 20th century, researchers discovered Vitamin D, and found that it is essential for bone development and a variety of other essential biological functions. In 1935, it was discovered that ultraviolet-B irradiation is responsible for the reaction producing Vitamin D in its active form. This provided an understanding of the mechanism by which UV-light was successfully used to treat rickets in the children of industrial smog-covered cities, several decades prior, during the Industrial Revolution.

In the 1920s, a Russian researcher named Alexander Gurwitsch discovered ultra-weak ultraviolet light emissions from living cells, which he called “mitogenic rays”, since they appeared to be the stimulus for mitosis, the process of natural cell division. A few decades later, Fritz-Albert Popp, a German researcher, discovered a wider spectrum of light emission from cells, and called this light “biophotons”, which he defined as “a photon of non-thermal origin in the visible and ultraviolet spectrum emitted from a biological system.” Thus, it was discovered that living cells actually generate, and even communicate with light.

More recently, in the 90s, scientists discovered that our eyes contain photoreceptor cells that don’t communicate with the image-forming centers of our brain, but rather wire directly to the hypothalamus—the master regulator of the brain—informing the brain about the time of day, controlling the “circadian rhythm”, and thereby stimulating and regulating the production of a wide variety of essential hormones, neurotransmitters, and other biomolecules. Light is the primary factor that controls this crucial biological rhythm.

In 2017, the Nobel Prize in Medicine was awarded to Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael W. Young for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm—another Nobel Prize for a landmark discovery involving the crucial role that light plays in our health and biology.

Lately, leading scientists and public health experts have taken a keen interest in light, with the likes of Andrew Huberman, Ph.D., a professor of neuroscience at Stanford University, bringing newfound attention to the importance of light en masse. Huberman has spoken in detail about the crucial role that light plays in our health and well-being, and of the importance of daily exposure to morning sunlight in order to stimulate our circadian clock, regulate our biological rhythms, support our sleep, and experience optimal health and well-being. In Episode #68 of his Huberman Lab Podcast, he said “I can think of no other form of energy—not sound, not chemical energy (so not drugs), not food, not touch—no form of energy that can target the particular locations in our cells, in our organelles, and in our body to the extent that light can. In other words, if you had to imagine a real-world surgical tool by which to modulate our biology, light would be the sharpest and the most precise of those tools."

Light.

“The Human Soul: Its Movements, Its Lights, and the Iconography of the Fluidic Invisible”, Hippolyte Baraduc. 1913.

When I was a kid, I never thought once that light could affect my health; or even that it played any more of a role in my life than simply allowing me to see. When the sun was out, there was light outside, so I could see. When I turned on a light in a dark room, there was light, so I could see. On a dark night, the moon reflected the light of the sun, so I could see, at least a little. The stars emitted beautiful, glowing, dim light from hundreds of millions of miles away, causing the night sky to glimmer with beautiful light. In the magic of Christmas time, we would adorn our tree with beautiful, twinkling lights, and these colored lights would shine all around, causing a special feeling in the air. A warm fire in the winter offered a kind of light that could warm the depths of my soul, and a bonfire with friends offered a kind of light that would burn permanent memories to be cherished for decades to come.

We don’t fully understand it, and we may never. But light, whether we know it or not, is the energy that powers our lives. It is the energy stored in our food, it governs our biological rhythms, it controls our biochemistry, our cells use it to communicate, and so much more. Even the top public scientists and health experts are beginning to emphasize the tremendous importance of a healthy “light diet”: with ample morning sunlight, a sufficient dose of strong daylight for vitamin D production (and much more), and a reduction of sleep-disrupting bright artificial light and screen devices in the evenings. As our collective human knowledge evolves, and our understanding of the world deepens, it may be the case that we return to certain fundamental truths, which have been known for millennia: intuitively, viscerally, if not “scientifically”.

“We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when men are afraid of the light.” Plato

Matt Maruca is an entrepreneur and journalist interested in health, science, and scientific techniques for better living, with a focus on the power of light. He is the Founder & CEO of Ra Optics, a company that makes premium light therapy products to support optimal health in the modern age. In his free time, he enjoys meditation, surfing, reading, and travel.

A Brief History of White Magic, Part 1.

Flora Knight June 4, 2024

The history of White Magic is the history of a middle way, and the history of harnessed imagination. Different from ‘Black Magic’, which is magic with the intention of harm or wrongdoing, White Magic is about transcendence, knowledge, self-improvement and the betterment of the world…

A medieval illustration of a magic circle, showing the middle way.

Flora Knight June 4, 2024

The history of White Magic is the history of a middle way, and the history of harnessed imagination. Different from ‘Black Magic’, which is magic with the intention of harm or wrongdoing, White Magic is about transcendence, knowledge, self-improvement and the betterment of the world. The very word "magi", from which our “magic” comes, is a Persian word for the learned class. White Magic is both high art and science, concerned with releasing the powers of imagination through a practiced harmony with the universe.

It begins in our earliest records and continues through to modernity. To fully understand it, we must see it as one of the three governing schools of thought that have existed since early civilisation, alongside science and religion. It is both a separate pursuit and a synthesis of these two, a middle way. The distinctions between these three schools can be best understood as:

1. In religion, one requests manipulation of the created universe by God or his agents.

2. In science, one manipulates parts of the created universe oneself.

3. In magic, one manipulates parts of the created universe with non-physical agencies.

In the ancient world, all three approaches were legitimate. In medieval times, religion was the only way forward, and dabbling in science and magic was considered impious. Today, in modernity, science has become the accepted way to understand the world, with increasingly less space for religion or magic. The magical mind understands magic as the link and reconciliation between science and religion, without condemning either.

It is ultimately difficult to disentangle these three threads across history for they have lived in a constant state of dialogue. Magic is ultimately a continuation of pre-Christian pagan ritual and Neo-Platonic thought—the earliest ideas of science and religion. While these two progressed and changed, magic at its core remained remarkably consistent. Nonetheless, its history reveals its subtleties.

I. Antiquity

The ancient world, in this case Egypt, Rome, and Greece, laid the foundations for all magic that followed. The distinctions in this era are less clear. Paganism and polytheism ruled, and magic was a part of daily life. The traditions and ideas that developed here informed all magic and witchcraft that followed. These cultures took from one another, and this interchange allowed for pagan tolerance, paganism at this time simply meaning the practicing of a religion outside of the ‘mainstream’, where Gods from each culture were absorbed into the others.

For the history of white magic, the most important pagan god is Thoth, also known, in Rome and Greece, as Hermes and Mercury respectively. Thoth is the god of magic, the moon, trade, learning, and books. Egyptian writing attributed to Thoth laid the foundations for all European magic that followed and Jewish influence in Egypt also helped create these base principles. It was during this time that an important distinction was made: that of the difference between theurgy and thaumaturgy, or high and low magic, respectively. Theurgy is the raising of consciousness above the material world to the realization of a restored world. Thaumaturgy, or sorcery, is the production of wonders by the powers of the mind. In the Jewish story of Aaron and Moses against the Pharaoh’s magicians, the men duelled each other by transforming rods into serpents. This was an act of Thaumaturgy and there is a close relationship between this form of magic and the religious ideas of miracles.

Stories and symbols from this era pervade the history of witchcraft and white magic. The Egyptian funerary rites, administered by Thoth, created the idea of ‘secret passwords’ or cryptic spells. The use of wax figurines, or voodoo dolls, also came from this process. Farming practices led to the idea of a guiding star, which was later adopted by Christianity and Masonic symbolism. In the world of ancient Egypt, the distinctions mentioned meant little; magic was intertwined with religion and science and all three combined as a way to understand the world.

A layout of the interior chambers of the Temple of Solomon.

Around 950BC, The Temple of Solomon was built in the then Egyptian city of Jerusalem. It is the most important physical site of magic, laying the building blocks of not just magical architecture but also sacred geometry and the conception of the magical universe as a whole. It was built to house the Ark of the Covenant and is the earliest forerunner of pagan mystery religions—a way of combining magic, paganism, and spirituality with mainstream religion. We see its influence in Templar magic, the Freemasons, and in the rise of ‘magic spell books,’ one of the most important in Renaissance magic being the ‘Clavicle of Solomon.’

II. Early Christianity

As Christianity spread across the world, four threads emerged that play a vital role in the history of white magic and witchcraft. These are Gnosticism, Hermetic literature, Neo-Platonic philosophy, and the Jewish Qabalah. Gnosticism was the amalgamation of pagan magic and Christianity. Hermetic literature reflected the Christian impact on Greek philosophy and Egyptian magic. Neo-Platonic philosophy was the resurgence of Greek thinking, and Jewish Qabalah was a form of Jewish mysticism. All four of these threads are essential to the conception of witchcraft, and there is endless scholarship on all of them. It is Hermetic literature and Qabalah, however, that have remained the most potent influence on modern witch-cults, the Golden Dawn, and Wicca itself.

A representation of the Qabalah Cube.

Qabalah didn’t flourish in its entirety until the Renaissance, but in the days of early Christianity, many of its ideas were conceived. In a brief history, the most encompassing for us is the Qabalistic Cube as a representation of the universe. The Qabalah was a break from Christian thinking, placing transcendence and introspection as its core tenets. The Cube was a representation of the universe that mirrored man's consciousness, a tree of life that placed all existence along a single thread. It was an early example, along with the Temple of Solomon, of a portrayed fourfold universe—an important number and conception in all later witchcraft. It also represented the twelve zodiac signs and assigned them characteristics, with mental activity represented by Mercury, love by Venus, order by Jupiter, and inspiration by the Sun. The Qabalah Cube consists of ten interconnected spheres, or sephiroth, representing different aspects of divine emanation and the journey of the soul. Each sphere embodies spiritual principles and cosmic forces, which together form a multidimensional map of existence. It is a tool for understanding the interconnectedness of the universe, the divine hierarchy, and symbolizes the eternal quest for unity and harmony within the cosmos. Through meditation and study of its intricate pathways, practitioners seek spiritual enlightenment and alignment with the divine will.

Hermetic literature is another important development of this era. These works took the form of compilations of allegedly ancient texts, attributed to an amalgamation of Thoth and Hermes. The most relevant is the Cyranides: put together in the 4th century, it is one of the earliest magic spell books, pertaining to mystic remedies, spells, and the practical and magical properties of plants, animals, and amulets. There were a whole host of Hermetic texts related to these properties, as well as groundwork for astrology and the foundations of alchemy. These texts are almost all lost and exist only in fragments, but their influence on witchcraft is paramount.

For the first thousand years of its recorded existence, white magic was a central way of understanding the world. It was not altogether a distinct path, but a necessary strand of thinking that informed and complimented religious and scientific thought. In these periods, each new culture and civilisation imbued it with their own mythology, ideas and conceptions and it adapted these disparate influences into a unique way of thinking which pervaded across the world. As Christianity began to spread, the magical way was forced underground, taking with it a millennia of hidden and forbidden knowledge.

Flora Knight is an occultist and historian.

The Knight of Cups (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel June 1, 2024

The Knight of Cups is a court card and the highest card in the suit of Cups. In each iteration we find a bluish gray horse, mounted by a fair haired rider bearing a cup. This is a card of confusion and desire…

Name: Knight of Cups

Astrology: Pisces, Fire of Water

Qabalah: Yod of He י of ה

Chris Gabriel June 1, 2024

The Knight of Cups is a court card and the highest card in the suit of Cups. In each iteration we find a bluish gray horse, mounted by a fair haired rider bearing a cup. This is a card of confusion and desire.

In Marseille, we find a rather plain rider, lacking the armor of the other two cards. He is smiling, holding a large golden cup with red detail. His horse appears satisfied. Both he and his horse have blonde hair.

In Rider, we find a much more determined figure, bearing a stern demeanor and firm grasp of his cup. He has a winged helmet, armor, and a tunic decorated with fish. His shoes are winged. His horse seems to hesitate as they prepare to cross a river and approach a mountain range.

In Thoth, we see a figure in the midst of great activity, his horse galloping ahead. He has dark armor and two large wings. His cup holds a crab, even though he is the image of Pisces. He is surrounded by waves, and beneath him is a peacock.

The image Rider and Thoth evoke to me is that of the Flying Fish, who leaps from his home in the sea to surf the waves with his fins. And just as the saying goes, the Knight of Cups is a “fish out of water”. He is Pisces as Flying Fish. His Knightly nature is that of Fire, but his suit is Water, meaning there is fundamental conflict; He is the Fish who fights against his own needs.

As such, we find the flying fish’s human correlation in the Surfer. One who leaves the land to dominate and harness the water. This is the nature of the Knight of Cups, surfing the power of the ocean, but never far from drowning.

Flying Fish, Kristen Middleton

Symbolically, we see this as the archetypal Grail Knight, the knight not only seeking the cup, but seeking to be worthy of the cup. The Grail Knight must have an absolutely pure and perfect Heart to be worthy of the Grail, but this is exceedingly rare, for the pure heart exists in opposition to our base drives. Like fire and water they combat each other. In the Grail stories this leads to terrible failure, with a character like Klingsor going as far as to castrate himself in an attempt to be pure enough for the Grail.

Thus this card is characterized by confusion and conflict. There is the overwhelming desire to obtain the Grail, to surf larger and larger waves, but it is always met equally by Nature, and it’s bestial demands to crawl in the dust of the Earth.

When dealt this card, we may be confronted with our own confused desires, or with a figure who embodies this conflict, it may even be as simple as a Pisces that we know.

The Poetic Diary of Ramuntcho Matta (Excerpt II)

Ramuntcho Matta May 30, 2024

How to become a better me?

But first, what do you call me? How do you call me? There are no special lines, no direct lines. There are only paths mades of confusions, pains and distraught. Paths mades of encounters, dances and sleeps…

Ramuntcho Matta May 30, 2024

I.

How to become a better me?

But first, what do you call me? How do you call me? There are no special lines, no direct lines. There are only paths mades of confusions, pains and distraught. Paths mades of encounters, dances and sleeps.

In the South of France there is a land that does not want to be a country. The people there do not want borders. Are there borders anyway?

I am here with a Basque cake, I sit on a bench and they come, all dressed in white, in red and strange hats.

All dressed in white?

It reminds me a song,

All dressed in black?

They come and they dance, each village has their own version. Does your body remember the dance? It does but you can’t recall.

Basque Identity is a moving cross, a representation of the four elements. But we know we have five elements. We have five fingers because we are five elements.

Every day, I will practice my five elements. Water > earth > wood > metal > fire. 3 times, sometimes more. This is the first exercise. At the beginning you will feel very little but after a few weeks you will start to enter in a new dimension and after 4 years you will be water, earth, wood, metal and fire.

You already have this in you but you are not trained to feed yourselves with those sensations.

II.

As a child becomes a flower when they see a flower…

you have to be water that becomes earth,

earth that becomes wood,

wood that becomes metal,

metal that becomes fire,

fire that becomes water,

water that becomes…

That becoming is the essence of being.

Being an animal,

being a human,

being a chair,

a nice meal,

an old stone.

The other day I was invited to present my drawings. In my life of brushstrokes, sometimes words show up. Where they come from is not relevant, where they drive me… that’s the point.

I started to play with my guitar and a dog showed up, so i wanted him to sing, and here we are, a dog’s song… the blues of a dog.

What is “me“ for a dog ? What is his “self“, his “I“? What is the balance between “I“ and “me“ that could make a better “self“?

A dog does not care about this because he does not care about knowing more: instead, he feels more. Much more.

I remember the song.

All dressed in black,

walking the dog,

being a dog…

III.

I can show you how to enter into that dimension. There are exercises and practices but if you are not ready it will be useless. Brion Gysin and Bill Burroughs wanted to create a school but very soon they felt that this kind of knowledge is not for everybody. So transmission should be more maieutics.

Back to the drawing: you see the triangle… “me“ is the body. “I“ the mind. How much of your body is your self? How much of your mind?

Do you mind?

Do you body?

“I don’t mind“,

What a curious sentence.

The rhythm of the phrases is at least as important as the meaning of the words. This is what Bill used to say.

Now you can feel more,

Feeling is not a knowledge

It is a dimension of being.

Ramuntcho Matta is a producer, sound designer and visual artist.

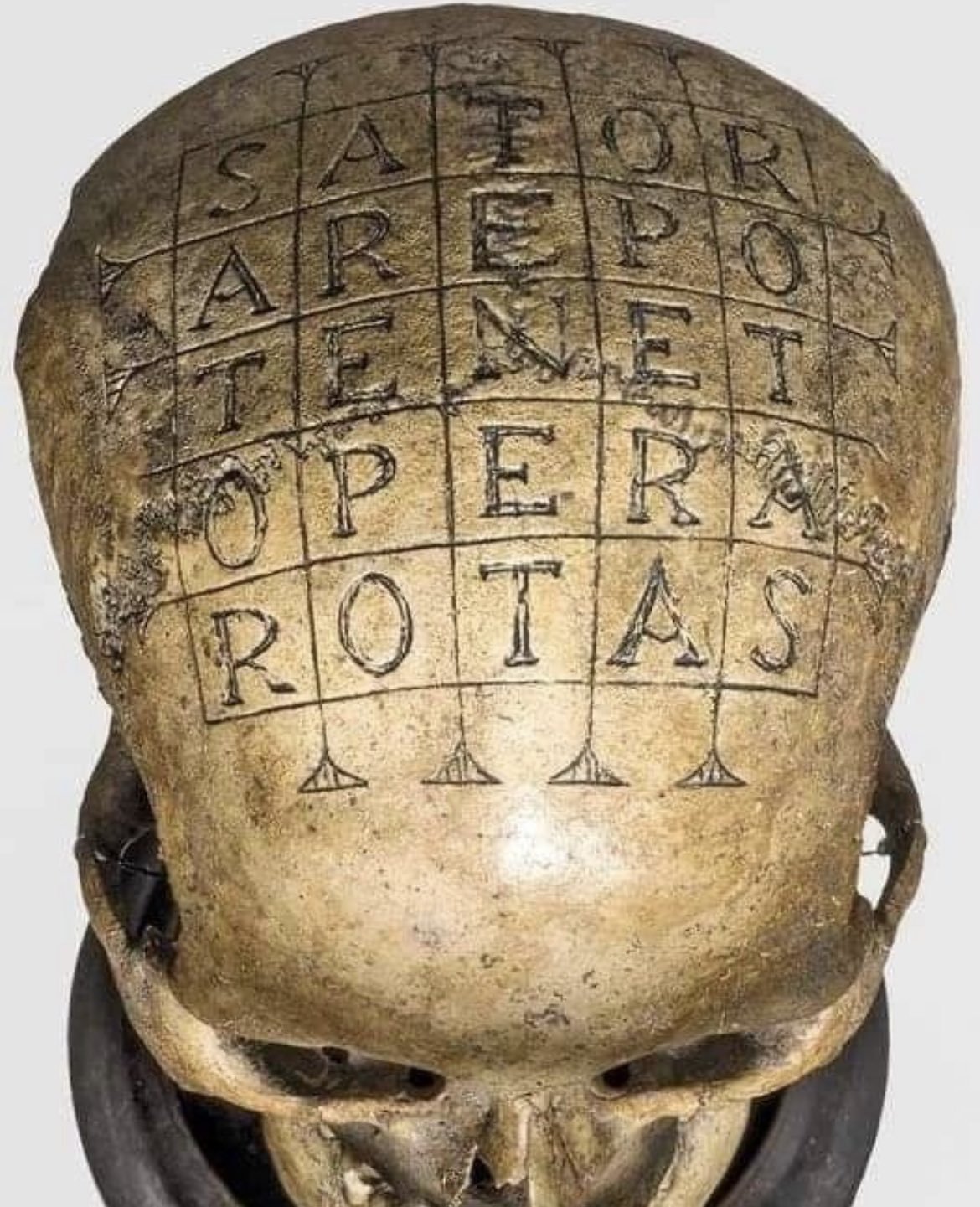

Sator Squares (Artefact III)

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies…

WUNDERKAMMER

Artefact No: 3

Location: Across Europe and the Americas.

Age: 2000 years

Ben Timberlake May 28, 2024

It might be innocently regarded as perhaps the world’s oldest word puzzles, were it not for its association with assassinations, conflagrations and rabies.

Sator Square in the village of Oppède le Vieux.

The “it” in question is the Sator Square. A Latin, five-line palindrome, it can be read from left or right, upwards or downwards. The earliest ones occur at Roman sites throughout the empire and by the Middle Ages, they had spread across northern Europe and were used as magical symbols to cure, prevent, and sometimes play a role in all sorts of wickedness. The one pictured here is set in the doorway of a medieval house in the semi-ruined village of Oppède le Vieux, Provence, France, carved to ward off evil spirits.

There are several different translations of the Latin, depending on how the square is read. Here is a simple version to get us started:

AREPO is taken to be a proper name, so, AREPO, SATOR (the gardener/ sower), TENET (holds), OPERA (works), ROTAS (the wheels/plow), which could come out something like ‘Arepo the gardener holds and works the wheels/plow’. Other similar translations include ‘The farmer Arepo works his wheels’ or ‘The sower Arepo guides the plow with care’.

Some academics insist that the square is read in a boustrophedon style, meaning ‘as the ox plows’, which is to say reading one line forwards and the next line backwards, as a farmer would work a field. Such a method would not only emphasize the agricultural nature of the square but also allow a more lyrical reading and could be very loosely translated thus: “as ye sow, so shall ye reap.”

“Early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stated that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.”

Sator Square with A O in chi format.

There are multiple translations and theories surrounding Sator Squares. They became the focus for intense academic debate about 150 years ago. Most of the early studies assumed that they were Christian in origin. The earliest known examples at that time appeared on 6th and 7th century Christian manuscripts and focussed on the Paternoster anagram contained within: by rearranging the letters, the Sator Square spells out Paternoster or ‘our father’, with the leftover A and O symbolizing the Alpha and the Omega.

However, in the 1920s and 30s, two Sator Squares were discovered within the ruins of Pompeii. The fatal eruption of Vesuvius that buried the city occurred in AD 79, and it is very unlikely that there were any Christians there so soon after Christ’s death. But the city did have a large Jewish community, and many contemporary scholars see the Jewish Tau symbol in the TENET cross of the palindrome, as well as other Talmudic references across the square, as proof of its Jewish origins. Pompeii’s Jews faced pogroms throughout their history, and it makes sense that they might try to hide an expression of their faith within a Roman word puzzle.

Sator Squares spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and appear in the margins of Christian manuscripts, in important treatises on magic, and in a medical book as a cure for dog-bites. Over time, they gained popularity amongst the poor as a folk remedy, even amongst those who had no knowledge of Latin or were even illiterate. (Being ignorant of meaning might increase the potency of the magic by concealing the essential gibberish of the script). In 16th century Lyon, France, a person was reportedly cured of insanity after eating three crusts of bread with the Sator Square written on them.

As the square traveled across time and country, nowhere was it used more enthusiastically than in Germany and parts of the Low Countries, where the words were etched onto wooden plates and thrown into fires to extinguish them. There are early fire regulations from the German state of Thuringia stating that a certain number of these magical frisbees must be kept at the ready to stop town blazes.

Oath Skull with Sator Square carved into bone.

From the same period comes a more sinister use of the square: The Oath Skull. Discovered in Münster in 2015 it is a human skull engraved with the Sator Square and radiocarbon dated between the 15th and 16th Centuries. It is believed to have been used by the Vedic Courts, a shadowy and ruthless court system that operated in Westphalia during that time. All proceedings of the courts were secret, even the names of judges were withheld, and death sentences were carried out by assassination or lynching. One of the few ways the accused could clear their names was by swearing an oath. Vedic courts used Oath Skulls as a means of underscoring the life-or-death nature of proceedings, and it is thought that the inclusion of the Sator Square on this skull added another level of mysticism - and the threat of eternal damnation - to the oath ritual.

When the poor of Europe headed for the New World, they took their beliefs with them. Sator Squares were used in the Americas until the late 19th century to treat snake bites, fight fires, and prevent miscarriages.

For 2000 years, interest in the Sator Squares has not waned, and a new generation has been exposed to them through the release of Christopher Nolan’s film TENET, named after the square. The film, about people who can move forwards and backwards in time, makes other references too: ‘Sator’ is the name of the arch villain played by Kenneth Branagh; ‘Arepo’ is the name of another character, a Spanish art forger whose paintings are kept in a vault protected by ‘Rotas Security’. In the film, ‘Tenet’ is the name of the intelligence agency that is fighting to keep the world from a temporal Armageddon.

Sator Squares have been described as history’s first meme. They have outlasted empires and nations, spreading across the western world and taking on newfound significance to each civilization that adopts them. Arepo should be proud of his work.

Ben Timberlake is an archaeologist who works in Iraq and Syria. His writing has appeared in Esquire, the Financial Times and the Economist. He is the author of 'High Risk: A True Story of the SAS, Drugs and other Bad Behaviour'.

The Four of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 25, 2024

The Four of Swords is air, at a point of stillness and equilibrium. This is a card of calm, and of temporary resolution to internal problems…

Name: Truce

Number: 4

Astrology: Jupiter in Libra

Qabalah: Chesed of Vau ו

Chris Gabriel May 25, 2024

The Four of Swords is air, at a point of stillness and equilibrium. This is a card of calm, and of temporary resolution to internal problems.

In Rider, we see a Gisant, or a tomb effigy. A young man depicted at rest, his image forever in prayer. His tomb bears a sword, and above him are the other three. In the top left corner, a stained glass window depicts a priest giving rites to a kneeling person.

In Thoth, we see four swords aimed at the center of a flower, forming a cross. We have the purple of Jupiter and the green of Libra. This is an expansive peace, a magnanimous truce. It calls to mind the Christmas Truce of World War 1 - out of jollity and a higher spirituality came temporary peace and mutual joy.

In Marseille, we have four arched swords and a central flower. Through Qabalah, we arrive at the Chesed of Vau, or the Mercy of Prince. The Mercy of the Prince is a Truce.

In this card we see beautiful but fragile rest, the violence of the suit brought to a brief standstill out of reverence to a higher force. This is a family dinner with differences put aside, a holiday party when bitter relatives agree to keep the peace for the sake of the season. There is something “higher” calling us to pause personal conflicts, whether it’s the religiosity and “goodwill” of a holiday, or the wellbeing of children and family. This is precisely the realm of Jupiter, that mercy and joy that beneficently orders conflict to cease for a moment.

This is in no way a solution, and may very well devolve into conflict if not carefully maintained, but it is a respite. We also see a serious divide in spiritual outlook between Rider and Thoth, when four, the stable number, is applied to swords. Is stability only truly attained in the grave? Or can a brief armistice give us the same thing?

Hamlet, yearning for peace, declares death the only end to heartache and the thousand natural shocks, but even then, the fear that this rest is illusion pervades his mind.

When dealt this card, we are being offered a temporary resolution, either to the internal conflicts within our restless minds, or the disagreements we have with those around us. Keep the truce, appreciate the respite, but prepare for things to break down, and quickly!

The Power of Regret

Claudia Cockerell May 23, 2024

In the winter of 1981, a 22-year-old Texan called Bruce was on a train through Europe. A girl boarded at Paris and sat down next to him. They started chatting, and it felt like they’d known each other their whole lives. After a while they were holding hands. When it came to her stop they parted ways with a kiss. They never traded numbers, and Bruce didn’t even know her surname. “I never saw her again, and I’ve always wished I stepped off that train,” he wrote, 40 years on, in his submission to The World Regret Survey.

Melancholy, 1891. Edvard Munch.

Claudia Cockerell May 23, 2024

In the winter of 1981, a 22-year-old Texan called Bruce was on a train through Europe. A girl boarded at Paris and sat down next to him. They started chatting, and it felt like they’d known each other their whole lives. After a while they were holding hands. When it came to her stop they parted ways with a kiss. They never traded numbers, and Bruce didn’t even know her surname. “I never saw her again, and I’ve always wished I stepped off that train,” he wrote, 40 years on, in his submission to The World Regret Survey.

It’s a website you should visit if you ever need some perspective. Set up by author Daniel Pink, it asked thousands of people from hundreds of countries to anonymously share their biggest regrets in life. It’s strangely intimate, delving into the things people wish they’d done, or not done at all, and the answers run the gamut of the human condition.

For all the people who regret cheating on their partners, there are just as many who wish they’d never married them in the first place. One 66-year-old man in Florida regrets “being too promiscuous,” while a 17-year-old in Massachusetts says “I wish I asked out the girls I was interested in.” The stories range from quotidian (“When I was 13 I quit the saxophone because I thought it was too uncool to keep playing”) to tragic (“Not taking my grandmother candy on her deathbed. She specifically requested it”).

Sometimes we feel schadenfreude when reading about other people’s failings, but there’s something about regret that is pathos-filled and painfully relatable. Flicking through the answers, many of people’s biggest regrets are the things they didn’t do. We fantasise about what could have been if only we’d moved countries, switched jobs, taken more risks, or told someone we loved them.

“It just wasn’t meant to be. I still long for the sea - and to be near the waves”.

Pink wrote a book about his findings, called The Power of Regret. “We’re built to seek pleasure and to avoid pain - to prefer chocolate cupcakes to caterpillar smoothies and sex with our partner to an audit with the tax man”, he states. Why then, do we use our regrets to self-flagellate, more often wondering “if only…” rather than comforting ourselves with “at least”?

“One of the biggest regrets I have is not moving to California after graduating college. Instead I stayed in the midwest, married a girl, and ended up getting divorced because it just wasn't meant to be. I still long for the sea - and to be near the waves,” writes one man in Nebraska. This pining reflects the rose tinted lens through which we look at what could have been. California with its rolling waves and sandy beaches is synonymous with a life of freedom, love, and joy.

Studland Beach, 1912. Vanessa Bell.

Instead of categorising regrets by whether they are work, money, or romance related, Pink has created a new system, arguing that regrets fall into four core categories: foundation, moral, boldness and connection regrets. Within these groups, there are regrets of the things we did do (often moral), and things we didn’t do (often connection and boldness regrets). The things we didn’t do are frequently more painful because, as Pink says, ‘inactions, by laying eggs under our skin, incubate endless speculation’. So you’re better off setting up that business, or asking that girl out, or stepping off the train, because of the inherently limited nature of contemplating action versus inaction.

The actions which we do end up regretting are often moral failings that fall under the umbrella of a ten commandments breach. As well as adultery, larceny and the like, there’s poignant memories of childhood cruelty. A 56-year-old woman in Kansas still beats herself up about something she did 45 years earlier: “Throwing rocks at my former best friend in 6th grade as she walked home from school. I was walking behind her with my “new” friends. Terrible.”

But regrets can have a galvanising effect, if we choose to let them. Instead of wallowing in the sadness of wishing we could rewind time, or take back something horrible we said or did, we can use that angsty feeling as an impetus for change. “When regret smothers, it can weigh us down. But when it pokes, it can lift us up,” says Pink. There’s an old proverb which has probably been cross-stitched earnestly onto many a cushion, but I still like it as a mantra for overcoming pangs of regret: “The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second-best time is today.”

Claudia Cockerell is a journalist and classicist.

Grasping at Gesture

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

Hand Catching Lead, 1968. Richard Serra.

Isabelle Bucklow May 21, 2024

In the first of these texts on gesture, I traced an unreliable and partial history of hand gestures – from roman orators and Martine Syms, to teens on TikTok and TikToks of tech bros using Apple Vision Pro – and how, somewhere along the way we lost our gestures, or lost control of them; gesticulating wildly in the open air.

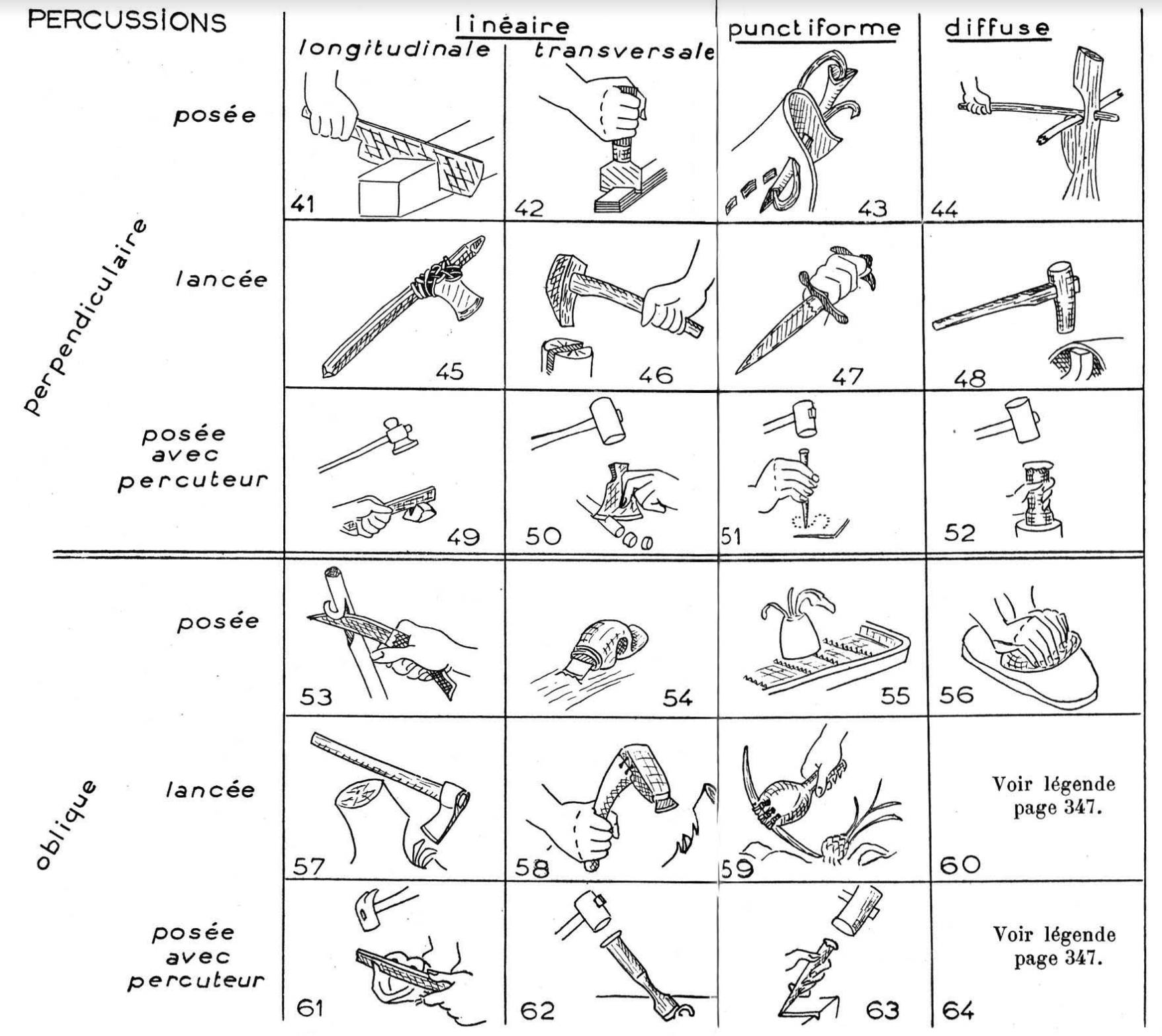

Man and Matter, 1943. Leroi-Gourhan.

Whilst gestures are certainly not always in or about the hands, a hand, like a grain of sand, can be revelatory of whole worlds. In medicine and mysticism, the study of hands discloses underlying health conditions, your character, your life trajectory. Hands provide a helpfully concise locale from which to study how we communicate, behave, make, and think and what all that has to do with gesture. And so, for now, we’ll pursue them a little further, homing in on one particular muscular operation of the hands: grasping.

‘The essential traits of human technical gesticulation are undoubtedly connected with grasping’¹ said Andre Leroi-Gourhan in his 1965 book, Gesture and Speech. A pioneering anthropologist, Leroi-Gourhan traced evolving relationships between hands, tools, gestures, languages, and thoughts, and developed a corresponding science for such. He is associated with Structuralist school, which means that he sought out the underlying processes (or structures) that make systems meaningful. Leroi-Gourhan’s Gesture and Speech does many things: It traces a bio-cultural evolution of postures, hands, brains, tools, art and language, up to the present day; conducts cross-cultural analysis of the rhythms and organization of human society, value systems, social behavior and techno-economic apparatus; and, amidst nascent developments in robotics and early experiments in automation, speculates on the future of our species.

“Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot.”

Alcuni Monumenti del Museo Carrafa, 1778.

The book begins with a history of the human brain and hand, with Leroi-Gourhan explaining: ‘it seemed to me that the first thing to do was to measure the results of what can be done with the hand to see what [our]brains can think.’² In pursuing both brain and hand he opposed the prevailing approach in evolution studies to focus only on the ‘cerebral’. Leroi-Gourhan was interested in how thought is embodied, how it springs from material conditions.

So, what can be done with the hand? Once we started walking erect on two feet, our hands were liberated from locomotion and, lifted from the ground, free to do an awful lot; they could grip and grasp and gesture. Now grasping is not specific to humans – qualitatively, the hand that grasps remains a relatively rudimentary device that's accompanied us across many evolutionary stages – and there are a variety of types and properties of grasps. Studying the transition from instinctive to cultural uses of hands, Leroi-Gourhan observed the functional shift from the mouth to the hand, from the hand to the grasped tool, and finally the hand that operates the machine. When it comes to grasping, ‘the actions of the teeth shift to the hand, which handles the portable tool; then the tool shifts still further away, and a part of the gesture is transferred from the arm to the hand-operated machine’. This he describes as a gradual exteriorization, or ‘secretion’ of the hand-and-brain into the tool.

But gesture still somewhat eludes us, its location ambiguous. Gesture is not in and of the hand, nor in and of the tool, rather gesture is the meeting of brain, hand and tool, the driving force and thought that sets the tool to action. To bring these gestures to light, Leroi-Gourhan developed the methodology for which he is best known: the Chaîne Opératoire.

The Chaîne Opératoire, or operational chain, is a method that makes processes visible by documenting the sequence of techniques that bring things into being – be they tangible artifacts, ephemeral performances, or even the acquisition of intangible status. Leroi-Gourhan described a technique as ‘made of both gesture and tool, organized in a chain by a true syntax’. The use of ‘syntax’ here (Structuralists had a thing for linguistics) establishes a relationship between the processes and the performance of language where there is room for both shared meaning and individual flourishes. Here, gesture, like the arrangement of words in a sentence, is relational, acquiring its shape and meaning through the interaction of mind, body, tool, material and social worlds in which it participates.

This whole time thinking about grasping hands I’ve had a film in mind: Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead, in which morsels of lead fall from above, are caught, and then released by the artist's hand. Far from mechanically consistent, sometimes Serra grasps the object, sometimes he grasps at it, narrowing missing and smacking fingers to palm. From 1968 into the early 70s Serra made a series of other hand films whose subject matter are just as the titles suggest: in Hand Catching Lead a hand, of course, catches lead; in Hands Scraping (1968) two pairs of hands gather up lead shavings which have accumulated on the floor/filled the frame; in Hands Tied two tied-uphands untie themselves.

“The creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool.. can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties.”

Hands Scraping, 1968. Richard Serra.

Curator Søren Grammel said Serra’s hand works ‘demonstrate a particular action that can be applied to a material’. I suppose that’s what the Chaîne Opératoire gets at too, as well as demonstrating how the material acts on us; in Hand Catching Lead, the lead rubs off onto Serra’s blackened hands. And just as the Chaîne Opératoire observes the network of gestures that fulfill an operation, the duration of Serra’s films cosplay pragmatism, lasting as long as it takes to complete the task (however arbitrary): How many pieces of lead can you catch or not catch until you are exhausted/cramp-up/are no longer interested? How long does it take to sweep up lead shavings or untie a knot?

Serra’s Hand Catching Lead was prompted in part by being asked to document the making of House of Cards (a sculpture where four large lead sheets are propped against one another to form the sides of a cube). But a film following the making process would, he felt, be too literal and merely illustrative. Instead, Hand Catching Lead is a ‘filmic analogy’ of the creative process. Serra knew that the creative gesture evaded standard step by step documentation. And, in fact, even a pretty sharp representational tool like the Chaîne Opératoire can’t fully grasp all of a gesture's subtleties. It seems we have come up against the limits of this approach, and of Structuralism's commitment to linguistics. Returning to Agamben, who we met in the first text: ‘being-in-language is not something that could be said in sentences, the gesture is essentially always a gesture of not being able to figure something out in language; it is always a gag in the proper meaning of the term…’³ Perhaps then Serra’s grasps are gags, grasping at lead, at air and at the irrepresentable nature of being-in-gesture.

¹ Andre Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1993) [1965]), 238

² ibid.,146

³ Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000) 59

Isabelle Bucklow is a London-based writer, researcher and editor. She is the co-founding editor of motor dance journal.

The Six of Swords (Tarot Triptych)

Chris Gabriel May 11, 2024

The World card is a cosmogram, meaning it depicts the whole of the cosmos. We find a naked woman floating within a ring, her legs crossed and something flowing about her. She is Maya, the embodied force of creation and illusion. Her dancing and spinning manifests the material world. The Four Cherubs frame the corners as symbols of the states of matter…

Name: Science

Number: Six

Astrology: Mercury in Aquarius

Qabalah: Tiphereth of Vau ו

Chris Gabriel May 18, 2024

The Six of Swords is a rare positive card in the suit. Here the winds of thought are well directed, and applied with intention and effect. This is a card of knowledge, and the acquisition thereof.

In Rider, we find a ferryman guiding a skiff with a huddled woman and child. The sky is grey, and the waters before them are still. This is a card of safety and retreat, and especially in the context of the grim visages that fill the suit of Swords, this is a positive card.

In Thoth, we find six swords aimed directly at a rose within a cross. About the swords are a geometric figure, a squared circle that has formed out of the chaotic shapes fluttering about the borders. We have the purplish greys of Aquarius and the gold of Mercury. This is the cross of the Rosicrucians. This card is the mind understanding the machinations of the universe.

In Marseille, we see six arched swords and a central flower. Qabalah tells us the six of swords is Tiphereth of Vau, or the Beauty of the Prince.

The Beauty of the Prince is his science, the way he learns, understands, and applies that knowledge.

As I’ve expressed before, the suit of swords evokes Hamlet, and this is the image of Hamlet the Scientist, Hamlet the Psychologist. Seen as such, we can interpret a great deal of Hamlet’s actions as experiments; consider the Mousetrap. Hamlet hypothesizes that Claudius kills his father, he puts on a play he calls “The Mousetrap” to prove this. The play’s the experiment!

As for Rider, we can think again to Hamlet, to his general ability to survive the treacherous court, feigning madness, going unpunished for murder, making off with pirates, evading execution, etc. His death is in many ways a suicide (which we’ll see later in the suit). But clearly, his understanding of his situation allows him to survive and escape death.

Thoth shows this science applied to the rosy cross, which is the symbol on the back of all Thoth cards. The rosy cross is a cosmogram, whose arms are the four elements, and whose petals are the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. In essence, an esoteric depiction of the universe, making this card a symbol of esoteric study itself.

When dealt this card we are being given an opportunity to develop our understanding of the things around us, to create a science of ourselves, and to then apply that knowledge in our lives.

More Than Meets the Eye - 1. Light, Science, Life.

Matthew Maruca May 16, 2024

In 1917, halfway through a career of developing theories and equations that changed our understanding of the world, Albert Einstein famously said “for the rest of my life, I will reflect on what light is.”

"Spectra of various light sources, solar, stellar, metallic, gaseous, electric" - Les Phénomènes de la Physique (1868). René Henri Digeon

Matthew Maruca May 16, 2024

In 1917, halfway through a career of developing theories and equations that changed our understanding of the world, Albert Einstein famously said “for the rest of my life, I will reflect on what light is.”

Substance or energy? Particle or wave? Light is a mysterious force, which links our internal experience to the external world. Or, does it create our internal experience, from the external world?

In our basic experience, light allows us to see. From the youngest age, we come to know that the “light switch” illuminates a dark room, allowing us to experience the room, without bumping into objects, tripping over things, and hurting ourselves. The world is already there, and we are a part of it, but without visible light, our conscious experience of the world is significantly limited. And it is vastly expanded by the presence of light.

We must then ask if this biological, biochemical, photochemical phenomenon that we call “light” allows our brain to consciously experience the material world around us, or if it is light that is actually creating our experience of the world. When the light is gone, we don’t have the same experience of the world; and when it’s present, we do. So it must be - in some way - creating our experience. What then, are we actually experiencing? To answer this, we must understand what exactly light is.

Light. And Science.

From the Bible to the Big Bang, several of the most influential stories of creation start with vibration or energy, which is not light. In many religions, this is the “Word”, the Cosmic Sound “Aum”, the voice of God the Creator; in science it is simply considered vibrational energy. And then, after the vibration, there is light.

Le Monde Physique (1882). Alexandre-Blaise Desgoffe.

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night.

And the evening and the morning were the first day.”

(Genesis 1:1-5, KJV)

This Biblical account of creation, where the voice of God is speech, is sound and vibrations, and comes before light is reflected in the scientific accounts of the origin of the universe. Light did not appear until some 380,000 years after the initial “Big Bang”, and while the first photons were created shortly after the Big Bang, they were immediately re-absorbed by different particles and so the universe was “opaque” during this time. Only after the universe cooled to a temperature of around 3000K, could protons and electrons begin to combine to form hydrogen, allowing perceptible light to move freely without being immediately absorbed. And then, there was light, in the form that we see.

From the perspective of science, light is a form of energy, the result of one of the four fundamental forces (a.k.a “interactions”), which govern everything in the known universe. Light is the term we use to describe the visible range of the broader spectrum of “electromagnetic radiation”, which comprises both the light we can see, and forms of radiation we cannot see, such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared light, ultraviolet light, X-rays, gamma rays, and so on. The photons responsible for light are one of the fundamental particles created by the initial Big Bang.

It wasn’t until 1801, when a British physicist named Thomas Young performed an experiment called “the double-slit experiment”, that we began to grasp what light really is, a question we are still grappling with. Young projected light through two parallel slits in one surface, with another surface behind it. When the light hit the back surface, he expected to see a pattern showing the slits through which the light had passed. Instead, what he saw was several, spaced-out lines of light, indicating that the light traveled more like waves, canceling itself out in certain places, while becoming stronger in others. This opened up the debate as to whether light is really a particle or a wave.

It is understood that electromagnetic radiation, a spectrum that includes visible light as well as forms of radiation we cannot see, is created and emitted in the process of nuclear fusion. This began first in the origin of our universe and now occurs in stars such as our sun, when hydrogen atoms are pushed together under tremendous pressure to form larger helium atoms. Some of the matter which makes up these atoms is converted, but not created, into energy and radiated out as light.

Another common way that light is emitted is from electromagnetic interactions between energy and atoms. In a fluorescent lamp, electricity is injected into a tube filled with mercury vapor. The mercury atoms absorb this electricity but then become unstable and quickly re-emit it as mainly invisible light. This light is then absorbed by the phosphor coating on the inside of the tube, which converts it in a range that is visible to the human eye. and is then re-emitted. This process of conversion of photons with higher quantum energies into lower ones is called “fluorescence”. The energy began in the form of electricity on a copper wire being injected into the light tube (before this, it may have been energy trapped in coal, oil, or moving in the form of wind, solar, or geothermal energy, as well).

That’s just a brief summary of the science of light, what it is, and where it comes from. There is still so much we don’t understand about the nature of light but, we know, at least, that light is absolutely fundamental to our existence.

Light. And Life.

What would happen if the sun didn’t come up tomorrow or the next day and ever after? Very quickly, within days or weeks, Earth would begin to freeze. The energy of the sun provides the warmth which is a prerequisite for life on Earth but the sun offers more than warmth. The light that comes to earth powers photosynthesis—the production of all plant matter, powered by sunlight splitting water, allowing it to bind with carbon dioxide and make sugar, the basic building block of all plant matter. Without sunlight, no crops could grow and just as importantly, all of the ocean’s phytoplankton, and land’s jungles and rainforests would die, robbing the atmosphere of its oxygen. Without oxygen, complex life, which is based on energy-producing mitochondria that use oxygen to generate energy, would fail. Life on Earth is the result of the conditions provided by sunlight. Life is not just built by sunlight, but it is sustained by its power. Light is essential for keeping the “system of life” in motion.

Cloud Shadow With Red Diffusion Light During the Disturbance Period (1884). Eduard Pechuël-Loesche.

Earlier on, we established that light is a fundamental part of our conscious experience of the world. And while there are still questions as to the nature of lightself, we know even less about the nature of consciousness.The two are closely linked, and great spiritual teachers throughout history have described our consciousness as a form of energy which is either directly connected or very closely related to light.

Traditional Chinese Medicine speaks of “Qi”, the life force energy which courses through our meridians, giving us life, and, when out of balance, can lead to disease. People have practiced exercises like “tai chi” and “qi gong” for millennia to care for this energy. A very similar perspective exists in the traditional religions of India as the concept of “prana”, and practices like meditation and “pranayama” breathwork sustain, nourish, and enhance this vital “life force” energy. In the West, scientists have found tremendous benefits from meditation (a PubMed search on the term yields over 10,000 results), yet they lack clear, definite mechanisms to explain these effects. Many doctors and leading healthcare institutions are beginning to prescribe alternative treatments like acupuncture and meditation to support patients’ health and well-being. This “life force” energy may not exactly be light; it may be more like electricity. But in the same way that solar power can be converted into electricity, and electricity can be converted back into light in a lamp, these different forms of energy within us are related, even if we don’t fully understand them.

It’s clear that the existence of life on Earth is inextricably linked to the conditions given by sunlight. We could even say that life on Earth is the result of the conditions provided by sunlight. Life, as we know it, is a product of the interaction between sunlight and the elements on the Earth’s surface.

Matt Maruca is an entrepreneur and journalist interested in health, science, and scientific techniques for better living, with a focus on the power of light. He is the Founder & CEO of Ra Optics, a company that makes premium light therapy products to support optimal health in the modern age. In his free time, he enjoys meditation, surfing, reading, and travel.

What Do The Fungi Want?

Tuukka Toivonen May 14, 2024

Creative ideas grow, mutate and flourish through conversations between people. However casual or mundane, these exchanges have the potential to reveal novel possibilities, or dramatically shift the course of a fledgling idea. Direct interactions are a tremendous source of motivation for creators. The best ones possess a much-overlooked generative power…

Fly Agaric Watercolor, 1892. Leigh Woods.

Tuukka Toivonen May 14, 2024

Creative ideas grow, mutate and flourish through conversations between people. However casual or mundane, these exchanges have the potential to reveal novel possibilities, or dramatically shift the course of a fledgling idea. Direct interactions are a tremendous source of motivation for creators. The best ones possess a much-overlooked generative power.

This was the basic premise of the research I was involved in as a sociologist until, a few years ago, I stumbled across interspecies creativity. I had become intrigued by how certain colleagues – designers and artists, especially – spoke passionately about how they sought to ‘create with and for nature’ or even ‘as nature’ when making new textiles, garments or artworks. They felt strongly that it was time to start treating living organisms and ecosystems as genuine collaborators and co-creators in their process.

Atlas des Champignons (1827). M. E. Descourtilz,

Spellbound by the prospect of novel ideas and designs emerging from humans collaborating with algae, mycelium and slime mould, I started to wonder about the practical and philosophical implications of such phenomena. For me, the question was not only about understanding the material qualities of particular organisms, it was about how humans might transform themselves into genuine co-creators in relation to nonhumans.

The notion of ‘creating with nature’ can be confounding – it was for me. Beyond the crude physical barriers that keep nonhuman and human lives separate, prevailing worldviews order us to place animals, plants, insects and fungi in a fundamentally different category from humans who – whilst animal – have developed complex cultures, technologies and societies, making us ‘unstoppable’, even ‘superior’. As a result of this human-centric conditioning, we are hopelessly unaccustomed to viewing nonhuman life as intelligent. Experts of human organizational life argue that perspective-taking – in essence, making an effort to imagine the point of view of another person or persons – is key to successful communication and management, and even constitutive of our ability to be ‘fully human’. There is no such chorus calling us to seriously listen or sensitize ourselves to the perspectives of nonhumans.

To explore species-crossing creativity further (in the hope of transcending or ameliorating the non/human barrier), we decided to hold in-depth conversations with a dozen biodesigners and bioartists, as well as a few progressive entrepreneurs. The creators were growing sneakers with bacteria that produce nanocellulose, working with microalgae to purify water contaminated by fashion dyes, and sewing fabrics from wild plants, among other fascinating experimental practices.

One outspoken participant explained that, in the early stages of the creative process, he always sought to engage as directly and viscerally with a living organism as possible, relentlessly looking for promising ways to collaborate. Having developed a particular interest in working with mycelium at a mass scale, he soon became curious not only about the material co-design possibilities of this organism, but also its behaviours and its needs. A simple yet pivotal question emerged: ‘What does the fungi want?’ His next steps as a designer and entrepreneur would be derived from that simple query.

Nearly all the creators we spoke to expressed an active curiosity about the needs of the organisms they were engaging with. Working with diverse plant species as well as digital technology, one participant recounted how she explored the way plants sense the world, their sensitivity to light and sound, and their ways of communicating with other organisms. Another spoke of the profundity of learning to collaborate with organisms whose existence on earth predated that of humans by millions of years.

“By subtly observing and interacting with diverse organisms, creators can establish equality of existence with all forms of life.”

The Intruder (c.1860). John Anster Fitzgerald.